Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections: Necrotizing Fasciitis, Gangrenous Cellulitis, and Myonecrosis: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) include gangrenous cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and anaerobic myonecrosis. All of these conditions are highly destructive locally, and they frequently have severe or lethal systemic complications; they must be recognized early and treated aggressively, usually with a combination of antibiotics, surgical debridement, and supportive measures. However, the infrequency of these infections, coupled with the relatively nonspecific clinical findings early in their course, makes rapid diagnosis difficult; up to 85% of these patients do not have an accurate diagnosis at the time of admission to the hospital.1

Necrotizing fasciitis, especially the monomicrobial form, frequently affects young, healthy patients. However, increased age, immunocompromise including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), chronic illness, alcoholism, and percutaneous drug use are risk factors.2 A chart review from New Zealand found that features common to a high proportion of necrotizing fasciitis patients included diabetes mellitus, gout, congestive heart failure, and recent surgical procedures. However, statistical analysis to assess the validity of these associations was not presented.3 Necrotizing fasciitis arising at sites of recent tattoos4,5 and sclerotherapy has been reported.6 Finally, the role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) is controversial; many studies have found an association between NSAIDS and necrotizing SSTI, but prospective studies have failed to confirm the speculation that NSAIDS may promote infection progression or delay diagnosis by obscuring early symptoms.7

Clostridial necrotizing SSTI, including anaerobic cellulitis and myonecrosis, arise either from deep traumatic or surgical inoculation, or from hematogenous spread from an internal infectious focus.8 These infections are rare in healthy patients; common associations include malignancy, neutrophil dysfunction, bowel ischemia, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome.9

Etiology, Microbiology, and Pathogenesis

The most common pathogens mediating necrotizing SSTI are group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GAS) in the case of necrotizing fasciitis type II, and anaerobes such as clostridial species in the case of gangrenous cellulitis and myonecrosis. However, other relatively common organisms that cause necrotizing SSTI include Staphylococcus aureus, non-group A streptococcal species, Pseudomonas, Pasteurella, Vibrio, and Enterobacteriaceae (such as Escherichia coli).8,10 These infections are often polymicrobial, with a mix of both pathogens and contaminants (see Table 179-1).

Type of Infection | Most Common Cause(s) | Uncommon Causes |

|---|---|---|

Gangrenous Cellulitis | ||

Clostridial anaerobic cellulitis | C. perfringens | C. novyi, C. sordellii, C. septicum |

Non-clostridial crepitant cellulitis | Bacteroides sp., Peptostreptococci | E. coli, other enterobacteriaceae |

Gangrenous cellulitis in the immunosuppressed individual | P. aeruginosa (ecthyma gangrenosum) Mucor, Rhizopus, Aspergillus | Bacillus sp., other bacterial and fungal sp. |

| Necrotizing Fasciitis | ||

Type I Polymicrobial infection with mix of anaerobes and facultative species | Anaerobes: Peptostreptococcus or Bacteroides sp. Facultative species: non–group A streptococci, Enterobacteriaceae | Groups B, C, and G streptococcus |

Type II | Group A streptococcus | |

Necrotizing Fasciitis Variants that Involve Extra-Fascial Cutaneous Structures | ||

Synergistic Necrotizing Cellulitis: Polymicrobial with facultative and anaerobic organisms that originate in the intestine: | Facultative coliform organisms: E. coli, Proteus, Klebsiella Anaerobic organisms: Bacteroides sp., or Peptostreptococcus | |

Progressive Bacterial Synergistic Gangrene (Meleney Gangrene) | S. aureus and Peptostreptococcus sp. | |

Infectious myositis | ||

Pyomyositis | S. aureus β-hemolytic streptococcus | S. pneumonia H. influenzae Enterobactereciae Mycobacteria Fungi |

Anaerobic myonecrosis (Gas gangrene) | C. perfringens | C. septicum |

The microorganisms associated with necrotizing cutaneous infections in the normal host are joined by a variety of other traditionally pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria, as well as fungi, in immunocompromised patients. In the presence of thermal burns, hematogenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa may infect normal skin, producing ecthyma gangrenosum (see Chapter 180), or may be attracted to burn areas, leading to extensive bacteremic pseudomonas gangrenous cellulitis. Mucormycotic gangrenous cellulitis can engraft onto thermal burns or complicate percutaneous catheter areas in immunosuppressed individuals. In the immunocompromised host, it becomes mandatory to biopsy any necrotic cellulitic lesions and to be alert to the possibility of a wide range of bacterial, viral, fungal, and even parasitic pathogens.

The pathophysiology of necrotizing fasciitis has not been fully elucidated, but the bacteria capable of producing this infection, including GAS, appear to share the ability to produce enzymes that degrade fascia and allow rapid proliferation at the level of the superficial fascia. This proliferation results in local thrombosis, progressive ischemia, liquefaction necrosis, and ultimately, more superficial gangrene.11

Mechanisms of clostridial virulence are better understood. Clostridial species are large spore-forming Gram-positive bacilli that produce more toxins than any other known bacteria.12 Clostridial α-toxin, a pore-forming lecithinase that mimics the function of phospholipase C, hydrolyzes cell membranes, and increases capillary permeability and platelet aggregation, thereby mediating hemolysis and dermonecrosis. This exotoxin has been shown to be both sufficient and necessary for gas gangrene in mouse models; injection of Bacillus subtilis carrying a gene for the toxin produces myonecrosis, and immunizing mice against the α-toxin prevents the infection.13 Nevertheless, other clostridial toxins do appear to play a role in human SSTI disease, including θ-toxin (containing perfringolysin O), ϵ-toxin, and multiple collagenases. Clostridium perfringens accounts for approximately 80% of clostridial SSTI; less common causes of gangrenous clostridial SSTI include Clostridium septicum, Clostridium novyi, and Clostridium sordellii.12,14

Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, Prognosis

Necrotizing infections of soft tissues may be localized to the muscle, fascia, or the overlying skin and subcutis, or they may cross these layers; the structural layers involved provide a useful framework for categorizing these infections into gangrenous cellulitis (affecting the dermis and subcutaneous tissue), necrotizing fasciitis (predominantly affecting the fascia), and pyomyositis and myonecrosis (affecting the muscle) (Table 179-2).

Feature | Progressive Bacterial Synergistic Gangrene | Synergistic Necrotizing Cellulitis | Streptococcal Gangrene | Clostridial Myonecrosis (gas gangrene) | Necrotizing Infections in Immunosuppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Microbiology | Streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus | Mixture of organisms: Bacteroides, peptostreptococci, or Escherichia coli | Group A streptococci | Clostridium perfringens | Rhizopus, Mucor, Absidia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Predisposing conditions | Surgery or draining sinus | Diabetes | Diabetes or abdominal surgery | Trauma | Diabetes, corticosteroid use, immunosuppression, burns |

Fever | Minimal | Moderate | High | Moderate to high | Low in fungal, high in pseudomonal |

Pain | Prominent | Prominent | Prominent | Prominent | Mild |

Anesthesia | Absent | Absent | May occur | Absent | May occur |

Crepitus | Absent | May occur | Absent | Present | Absent |

Course | Slow | Rapid | Very rapid | Extremely rapid | Rapid |

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis infections are often more extensive than the overlying skin changes would suggest. Early in the disease (stage 1), the involved area may be painful at first and then evolve with objective findings: swelling, erythema, warmth, and tenderness, resembling simple cellulitis.11 Constitutional symptoms with high fever and toxicity are characteristic of early progression, but at least one study of necrotizing fasciitis patients found fever in only half of patients, and hypotension in only 18%.15 It is possible that systemic manifestations are delayed or obscured by widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics at the first sign of a SSTI, when the disease is often thought to be a simple cellulitis.16 Within several days, induration worsens and bullae develop (stage 2). Ultimately, the skin color becomes purple and frank cutaneous gangrene ensues (stage 3) (Fig. 179-1). At this advanced stage, the involved area is no longer tender but has become anesthetic as a result of occlusion of small blood vessels and destruction of superficial nerves in the subcutaneous tissues.11,16–18

The classification of necrotizing fasciitis can be confusing because different variants have been described in the literature using unrelated criteria, including microbiologic features, anatomic location, and etiology.

Type I necrotizing fasciitis, a polymicrobial infection, is caused by a mix of facultative and anaerobic microbes, often delivered into the subcutaneous tissues after surgery, trauma, bowel perforation from neoplasm or diverticulitis, or injecting drug abuse via skin popping. It is by far the most common form of necrotizing fasciitis, accounting for nearly 90% of cases, often occurring in patients compromised by diabetes or malnutrition. Organisms include at least one anaerobic organism recovered in a mix of facultative microbes: nongroupable Streptococci, Enterococci, anaerobic Streptococci and Staphylococci, Bacteroides, and Enterobacteriaceae including E. coli, as well as various aquatic bacteria. Often, three to five species contribute to the infection, which may have a slower pace than GAS in evolving to a full-blown process with cutaneous manifestations.19,20

Type I necrotizing fasciitis most commonly occurs on an extremity, abdominal wall, perineum, or near operative wounds (see Fig. 179-1). It is important to recognize that when this infection presents in the thigh (dissection along the psoas muscle) or abdominal wall, it may be secondary to an intestinal source (occult diverticulitis, rectosigmoid neoplasm). Crepitus often develops, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus if gas-forming anaerobes, such as Bacteroides, are causative.

Type II necrotizing fasciitis is caused by a monomicrobial infection, usually GAS, which in this setting has been referred to as “flesh eating bacteria” by the lay press. If the process is not limited to the fascia, it is referred to as streptococcal gangrene. Occasionally, in the neonatal period, and very rarely in adults, group B Streptococci have been recovered.21 Other streptococcal species have been reported to cause monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis, including groups C and G Streptococci, as well as Streptococcus pneumoniae.22 In addition, monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) may be much more common than previously thought, with one recent study finding it to be the cause of nearly 40% of necrotizing fasciitis patients between 2001 and 2006.23

Patients may be immunocompromised by age or illness such as diabetes, alcoholism, or cirrhosis, but are usually healthy individuals. The location of the necrotizing lesion is most often an extremity and rarely, the face. The clinical presentation is usually indistinguishable from type I necrotizing fasciitis, but necrosis of the overlying skin can be particularly rapid and dramatic, revealing deeper structures, including tendon sheaths and muscle. Though lymphangitis is rare, metastatic abscesses can occur. Bacteremia is documented in approximately two-thirds of patients, and patients often develop a streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (see Chapter 177).24

Synergistic necrotizing cellulitis is a mixed infection of anaerobes and facultative bacteria generally classified as a type I necrotizing fasciitis because of prominent fascial involvement, but it actually may infect all soft-tissue structures, including skin and muscle. It is painful, progressive, and highly lethal, primarily affecting frail, elderly, diabetic, or obese patients, almost always with compromising cardiovascular and renal disease. The process may begin with only mild pain and low-grade fever, evolving slowly over 7–10 days. The initial skin lesion is a small reddish-brown bulla or patch on the perineum (near a perirectal or ischiorectal abscess) or lower extremity, with extreme local tenderness; the superficial appearance belies the widespread destruction of the deeper tissues. Skin sinuses (with surrounding areas of blue–gray gangrene) form, draining a foul-smelling thin pale “dishwater” exudate containing fragments of necrotic fat. Gas can be palpated in approximately one-fourth of patients. Half of the patients become bacteremic. Extensive gangrene of the superficial tissues and fat can be visualized by direct inspection through open skin areas or with skin incisions.25–27

Frequently isolated organisms include anaerobes (Streptococci and/or Bacteroides) and facultative bacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli, Proteus, and Klebsiella species).25,28 Rapid and extensive surgical debridement with antibiotics guided by the Gram stain is essential; nevertheless, the mortality rate remains in the 40%–50% range.27

Progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene is a specific polymicrobial infection, perhaps best categorized as a form of synergistic necrotizing cellulitis, which presents with a necrotic ulcer at the site of abdominal or thoracic incisions, wire-stay sutures, or fistulous tracts. The infection typically develops insidiously, within a week or two of a procedure. It is called synergistic because by definition, two or more bacteria must coinfect to create the clinical appearance, as demonstrated by Meleney who reproduced these ulcers by injecting microaerophilic Streptococci and S. aureus into animal skin; the infection did not develop when either pathogen was injected alone.27

These two variants of necrotizing fasciitis may be classified as either type I or type II, but they are defined and named by their anatomic location and etiology, rather than by their microbiologic profiles. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis is usually a type I infection (polymicrobial etiology), but GAS can be the single etiologic agent in rare cases, particularly in the setting of peritonsillar abscess formation. Most commonly, cervical necrotizing fasciitis originates from dental or pharyngeal sources. Crepitus may develop as the infection spreads to the face. This is in contradistinction to craniofacial necrotizing fasciitis, which starts in the face and is most commonly caused by GAS after a traumatic episode. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis carries a much higher mortality rate than the craniofacial variant.29–31

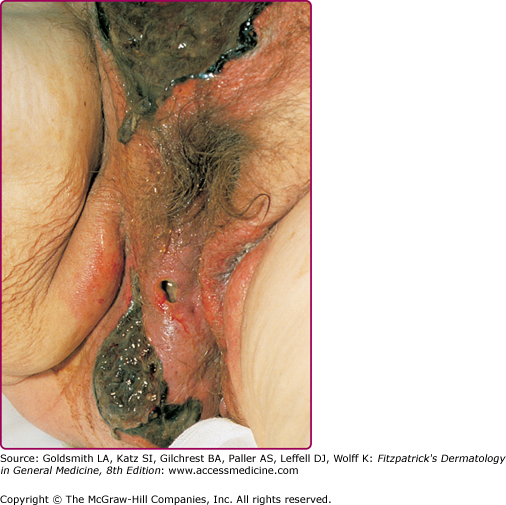

Fournier’s gangrene is a localized gangrenous SSTI involving the genitalia. The infection tends to be limited to skin and subcutaneous tissue of the genitals, but it may spread along fascial planes to the perineum and abdominal wall. It is usually caused by a mix of facultative and anaerobic organisms, and therefore is best categorized as a form of synergistic necrotizing cellulitis or type I necrotizing fasciitis. In rare cases, GAS as the single pathogen has been implicated, and this may be related to rectal ring carriage or to oral–genital sex. The average age at onset is 50–60 years of age. Most men have underlying diseases or a history of procedures. These include diabetes mellitus, ischiorectal abscess, perineal fistula, bowel disease (rectal or colon carcinoma, diverticulitis), scrotal or penile trauma, prior hemorrhoidal or urogenital surgery, pressure ulcers of the scrotum and perineum, paraphimosis and, rarely, obscure causes, such as dissection of pancreatic secretions through the retroperitoneum and into the scrotum in acute pancreatitis.32–34

The onset of Fournier’s gangrene can be insidious, with a discrete area of edema, erythema, and necrosis on the scrotum. Ultimately, skin necrosis begins to proceed rapidly over 1–2 days (Fig. 179-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree