I. INTRODUCTION

A. The keys to successful management of necrotizing soft tissue infections are early recognition and prompt aggressive surgical debridement.

B. These lesions may present with few external manifestations

C. Diffuse internal inflammation may progress rapidly with significant underlying deep tissue destruction.

D. A 24-hour delay in diagnosis and treatment may result in a mortality rate of 50%.

E. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with antibiotics and surgical debridement has decreased mortality to as low as 12%.

II. HISTORY

A. 1883: Fournier described a necrotizing infection of the scrotum (Fournier’s gangrene).

B. 1924: Meleney reported Streptococcal gangrene associated with bacterial synergism (Meleney synergistic gangrene).

C. 1952: Wilson described necrotizing fasciitis.

D. 1983: Greenberg reported necrotizing fasciitis with Group A Streptococcus/toxic shock syndrome (TSS).

III. RISK FACTORS

A. Impaired host defense mechanisms

1. Diabetes: As many as 70% of patients have diabetes.

2. Recent surgery

3. Peripheral vascular disease

4. Other factors include extremes of age, immunosuppression (transplant/HIV), lymphedema, and chronic systemic illnesses (cancer, chronic renal failure, and alcoholism).

B. History of trauma, burns, wound contamination, or foreign body

IV. PATHOGENESIS

A. A microaerobic wound environment promotes the growth of bacteria, leading to a local decrease in oxygen, producing a permissive environment for anaerobic bacteria.

B. The presence of proteolytic enzymes enhances the rate and extent of spread of infection.

C. Thrombosis of nutrient blood vessels to the skin and subcutaneous tissues produces more ischemic tissue, creating a vicious cycle.

V. PRESENTATION

A. Characterized by sudden presentation and rapid progression

B. The extent of infection is often diffuse with deeper tissues more affected than superficial ones.

C. Early signs

1. *Unexplained pain out of proportion to examination: May be the first sign

2. Cellulitis

______________

*Denotes common in-service examination topics

3. Presence of edema beyond the extent of erythema

4. Crepitus (present in only 10% of patients)

5. Skin vesicles or bullae: Represent deeper infection

6. Grayish watery drainage, “dishwater pus”

7. Coppery hue of the skin

8. Systemic signs: Fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea

D. Late signs

1. Cutaneous anesthesia

2. Focal skin gangrene

3. Shock, coagulopathy, and multisystem organ failure

VI. CLASSIFICATION

A. Type I: Polymicrobial infections—most common (80% of infections)

1. Gram-positive aerobes (Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, or Enterococcus faecalis) plus gram-negative aerobes (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., Clostridium spp., Bacteroides spp., or Peptostreptococcus spp.).

2. Bacterial synergism: Allows one organism to potentiate the growth of another

B. Type II: Monomicrobial infections—caused by three broad classes of organisms

1. Bacteria

a. Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

b. Clostridium perfringens—rapidly progressive (2 cm/h)

c. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

d. Rarely, gram-negative aerobes such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Vibrio vulnificus may be involved.

2. Fungus (e.g., Mucor): Can invade deeply, bypassing fascial planes

3. Protozoa: Rarely cause necrotizing infections (e.g., Entamoeba histolytica, Trichinella, Toxocara spp.). Meleney synergistic gangrene is thought to be caused by Entamoeba infection.

C. Important organisms

1. Clostridial necrotizing infections

a. Caused by multiple species of Clostridia, most commonly C. perfringens (80%), C. novyi (20%), and C. septicium; common contaminants of traumatic wounds.

b. A decrease in local oxygen tension results in spore activation

c. Production of multiple exotoxins: Most common is Alpha toxin (lecithinase), which causes cell membrane breakdown

d. The diagnosis of gas gangrene is made clinically

i. Necrotizing cellulitis has early local signs with moderate pain and involvement of superficial tissue.

ii. Myonecrosis presents with severe pain and involvement of deep tissues.

e. A gram stain of wound fluid reveals gram-positive rods without inflammatory cells.

2. Nonclostridial necrotizing infections

a. Streptococcal gangrene

i. Caused by hemolytic Streptococci

ii. Presents with rapid development of erythema over 24 hours with progression to blue-discolored bullae and then superficial gangrene in 4 to 5 days.

b. Meleney synergistic gangrene: Occurs post-operatively in surgical wounds, typically either thoracic or abdominal

c. Idiopathic scrotal gangrene

i. Fournier’s gangrene: Perineal gram-negative synergistic necrotizing cellulitis

ii. Causative organisms: Anaerobic streptococci

iii. Presentation: Sudden onset of fever and rapid development of scrotal gangrene and skin sloughing (24 to 30 hours).

A. Primarily based on clinical suspicion

B. Laboratory studies: Leukocytosis, elevated lactate

C. Soft tissue X-rays: Soft tissue gas present in only one-third of patients

D. Cross-sectional imaging

1. CT scan: Demonstrates soft tissue inflammation and gas

a. Sensitivity and specificity of 80%

2. MRI: May demonstrate similar findings to CT

a. Sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 50%

b. Limited by the lack of availability, cost, and time of study

E. Early tissue biopsy may facilitate early recognition of phycomycoses. Limited by the lack of availability of pathology 24 hours per day

VIII. MANAGEMENT

A. After diagnosing a necrotizing soft tissue infection, there are three required components of management.

1. Resuscitation

2. Broad spectrum IV antibiotic administration

3. Emergent radical surgical debridement

B. Antibiotic coverage

1. Broad coverage should be used until microbiologic analysis of the wound is available.

2. Current recommendations are

a. Piperacillin/Tazobactam PLUS Clindamycin PLUS Ciprofloxacin PLUS Vancomycin.

b. Penicillin, ampicillin, and β-lactams are effective for Clostridia, Enterococci, and Peptostreptococci. Clindamycin is excellent for anaerobes and has toxin-binding properties, and Gentamycin is effective against most Enterobacter and gram-negative species.

3. Single agent, broad spectrum drug therapy may be initiated using Meropenem or Imipenem/Cilastin in penicillin-allergic patients.

4. Amphotericin B should be started for demonstrated phycomycoses

5. Doxycycline for Vibrio vulnificus or Aeromonas infection

6. Human immunoglobulin may be helpful to patients with Streptococcal TSS, but current evidence is inconclusive.

7. Most importantly, antibiotic treatment alone is not enough. Surgical debridement of all devitialized tissues is required.

C. Radical surgical debridement

1. *Immediate operative debridement. Delay associated with nine times greater risk of mortality

2. Debridement of all necrotic tissues with intra-operative quantitative culture and biopsy specimens. Wound fluid gram staining should be performed.

3. Debridement should extend to viable tissue, with possible extremity amputation in clostridial gangrene, debridement of abdominal wall in Meleney synergistic postoperative gangrene, and creation of a testicular thigh pouch in Fournier’s gangrene.

4. Postoperative intensive care is usually required, with invasive monitoring, aggressive resuscitation, immobilization and elevation of involved extremities, and initiation of dressing changes (topical antimicrobial versus moist gauze).

5. Repeat exploration in 24 to 48 hours is performed, and remaining infected tissue is excised.

D. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO)

1. Can be used in conjunction with the above treatments for clostridial necrotizing infections although evidence is not conclusive.

2. There is no proven efficacy in nonclostridial infections

DOG AND CAT BITES

I. BACKGROUND

A. 50% of Americans will be bitten in their lifetimes: Dog bites account for 80% to 90% of these bites

B. Bite wounds (animals and humans) contain polymicrobial flora that represent the aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of the oral flora of the biter, the skin of the victim, and the environment.

C. Signs of infection usually do not develop until 24 to 72 hours

D. 80% of cat bites become infected

E. *Pasteurella species: Common, occurring in as many as 75% of cat bite infections

F. Anaerobes are also common in cat bites though usually not exclusively (Eikenella corrodens common)

G. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are commonly isolated from cultures

H. Other types of bacteria can also be involved as well, including Streptococci, Staphylococci, and anaerobes.

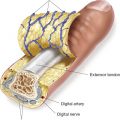

I. If involves the hand, important to rule out flexor tenosynovitis

II. TREATMENT

A. Clean and irrigate wound with sterile saline

B. Consider X-ray if concern for retained foreign body such as tooth

C. Debride devitalized tissue

D. Explore to determine if injury to deeper structures (in OR when indicated)

E. Prophylaxis for cat bites: Amoxicillin and clavulanate (Augmentin) or a combination of penicillin plus cephalexin.

F. Prophylaxis if allergic to penicillin

1. Moxifloxacin

2. Combination therapy with ciprofloxacin and clindamycin

3. Azithromycin may be effective for the penicillin-allergic patient, but it has less activity against anaerobes.

G. Pasteurella: Susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, second- and third-generation cephalosporins, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones, clarithromycin, and azithromycin, but resistant to cephalexin, dicloxacillin, erythromycin, and clindamycin.

H. Coverage for community-acquired MRSA infection is not recommended because oral colonization of the human and animal mouth with CA-MRSA is unlikely.

I. *Tetanus

1. Immune globulin and tetanus toxoid should be administered to patients who have had two or fewer primary immunizations.

2. Tetanus toxoid alone can be given to those who have completed a primary immunization series but who have not received a booster for more than 5 years.

J. Rabies prophylaxis

1. Indicated if laboratory evaluation found that the animal was rabid or because the animal was not captured.

2. Regimen for patients who have not been vaccinated previously should include both human rabies vaccine (a series of five doses administered intramuscularly in the deltoid area) and rabies immune globulin (20 IU per kilogram of body weight, with as much as possible infiltrated in and around the wound and the remainder administered intramuscularly at a site distant from that used for vaccine administration).

HUMAN BITES

I. INITIAL MANAGEMENT SHOULD CONSIST OF

A. X-ray to evaluate for retained tooth and/or fracture

B. Surgical exploration, especially in hand with tendon and metacarpal head evaluation

A. Augmentin (oral) or Unasyn (IV)

B. First-generation cephalosporins alone are not as effective due to resistant anaerobes and Eikenella corrodens.

C. Best to combine with β-lactamase-resistant penicillin

D. Cefoxitin and ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid are effective alone

E. Other alternatives include doxycycline, gatifloxin, and moxifloxacin; none of which are approved for children.

BROWN RECLUSE SPIDER BITES

I. ENTOMOLOGY

A. Loxosceles reclusa is identified by a violin-shaped mark on the dorsal cephalothorax and three pairs of eyes (most spiders have eight eyes).

B. It measures 1 to 3 cm in size and is often found indoors or outdoors in debris piles.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A. The bite presents with superficial erythema with surrounding purplish discoloration (6 to 24 hours).

B. Progression to full thickness skin necrosis often ensues (over more than 48 hours).

C. Systemic symptoms may include fever, myalgia, malaise, and/or GI upset (beginning at 12 to 24 hours).

III. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A. The spider’s venom is cytotoxic with protease, hyaluronidase, esterase, and sphingomyelinase components.

B. There is potentiation of the local neutrophil-mediated immune response with development of dermatonecrosis and systemic lymphokine response.

C. Histologic polymorphonuclear leukocyte perivasculitis with local hemorrhage also occurs.

IV. TREATMENT

A. Correct identification of the lesion can be difficult and is often delayed

B. Evaluate for other causes and monitor for systemic symptoms

C. Initial irrigation, local cold therapy, tetanus prophylaxis, and elevation of the affected extremity are helpful.

D. Close observation is provided for 72 hours

E. *Dapsone (a leukocyte inhibitor) should be initiated orally if a brown recluse spider bite is suspected. Dapsone is continued until the skin lesion resolves. *Hemolysis may result from Dapsone: Patients with G-6-PD deficiency may experience severe hemolysis and methemoglobinemia.

F. Systemic corticosteroids may have some benefit

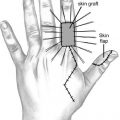

G. Surgical debridement with skin grafting is indicated if medical therapy fails and the lesion is well demarcated.

H. Failure of grafting is high: Around 15%

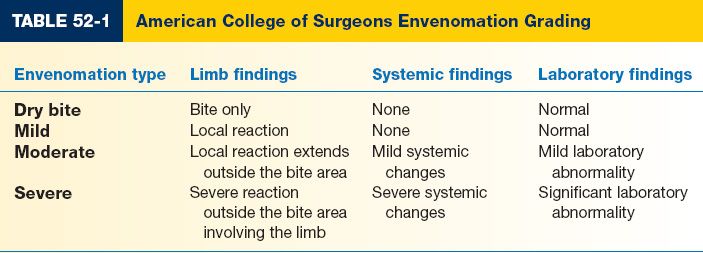

SNAKE BITES (TABLE 52-1)

I. BACKGROUND

A. 99% of snake bites are caused by the Crotalidae (pit viper) family of snakes: Rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths.

B. Rattlesnake bites deliver the most potent venom and are responsible for the majority of fatalities from snake bites; however, 10% to 50% of snake bites have been reported as dry bites.

C. Venom is proteolytic and consists of nonenzymatic proteins, peptides and other substances.

II. MANAGEMENT

A. Avoiding excessive activity of the affected site, immobilization in a neutral position, and expeditious transportation to a hospital.

B. *Antivenin is not recommended for dry bites (i.e., no clinical evidence of envenomation) or if envenomation appears to be mild.

C. *Indications for antivenin

1. Worsening local injury (e.g., swelling, pain, or ecchymosis)

2. Onset of clinical coagulopathy

3. Development of systemic effects including hypotension or changes in mental status.

4. Guidelines: Administration of 10 to 20 vials of antivenin after skin testing with horse serum for possible hypersensitivity reaction.

D. Debridement of the bite site and suction therapy have not been shown to be beneficial in reducing the effects of envenomation and can cause additional necrosis.

E. Fasciotomy: Only for clinical signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome and infection from extremity bites are extremely rare.

PEARLS

1. The appropriate acute management of necrotizing soft tissue infection is resuscitation, broad spectrum antibiotics, and radical surgical debridement.

2. Surgical debridement should extend back to viable, bleeding tissue. A “second-look” at 24 hours is mandatory.

3. Oral dapsone may have benefit when brown recluse spider bites are suspected.

QUESTIONS YOU WILL BE ASKED

1. What is often the first sign of a necrotizing soft tissue infection?

Pain out of proportion to examination.

2. What are the common bacteria associated with cat and dog bites?

Dog bites: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, Pasteurella multocida, and Bacteroides species; Cat bites: Pasteurella multocida.

3. What is best way to tailor antibiotic regimen?

Plan to send operative specimens for pathology and culture (gram stain, aerobes, and anaerobes). However, do not delay antibiotic administration pending cultures.

4. What is definitive treatment for necrotizing soft tissue infections?

Serial side surgical debridement.

Recommended Readings

Brook I, Frazier EH. Clinical and microbiological features of necrotizing fasciitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2382–2387. PMID: 7494032.

Fleisher GR. The management of bite wounds. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):138–140. PMID: 9887167.

George ME, Rueth NM, Skarda DE, Chipman JG, Quickel RR, Beilman GJ. Hyperbaric oxygen does not improve outcome in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009;10(1):21–28. PMID: 18991520.

Golger A, Ching S, Goldsmith CH, Pennie RA, Bain JR. Mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1803–1807. PMID: 17440360.

Jallali N, Withey S, Butler PE. Hyperbaric oxygen as adjuvant therapy in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189(4):462–466. PMID: 15820462.

King LE Jr, Rees RS. Dapsone treatment of a brown recluse bite. JAMA. 1983;250(5):648. PMID: 6864964.

Mills MK, Faraklas I, Davis C, Stoddard GJ, Saffle J. Outcomes from treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections: results from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Am J Surg. 2010;200(6):790–796; discussion 796–797. PMID: 21146022.

Ozturk E, Ozguc H, Yilmazlar T. The use of vacuum assisted closure therapy in the management of Fournier’s gangrene. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):660-665. PMID: 18789410.

Phillips BT, Bishawi M, Dagum AB, Khan SU, Bui DT. A systematic review of antibiotic use and infection in breast reconstruction: what is the evidence? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):1–13. PMID: 22965239.

Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):279–288. PMID: 19228540.

Swanson DL, Vetter RS. Bites of brown recluse spiders and suspected necrotic arachnidism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):700–707. PMID: 15716564.

Ustin JS, Malangoni MA. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(9):2156–2162. PMID: 21532474.

Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1454–1460. PMID: 12925624.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>