Nasal Reconstruction

Frederick J. Menick

Nature will heal almost any wound by secondary intention eventually. Any skin graft or flap or physician can close a defect. But human beings want to look normal. So nasal reconstruction is both a challenge and an opportunity for the specialty of plastic surgery. Success is determined by choice and compromise. The problem is analyzed, options are identified, limitations are appreciated, and the best solution is chosen to achieve the desired outcome.1,2

THE PATIENT

In some cases, age (a child less than 5 years of age or the extreme elderly), associated illness, or patient desire dictates a less complicated, quicker repair with minimal surgery or stages. The wound can be allowed to heal secondarily, closed with a skin graft or local flap, or, if full thickness, the skin and lining can be sutured to one another, accepting a permanent deformity. Unless underlying vital structures are exposed, an aesthetic repair can always be performed in the future. The occasional patient chooses a prosthetic reconstruction. However, most patients wish to live without deformity and seek surgical repair.

If a complex repair is planned, the surgeon must be aware that past surgical treatments for skin cancer, radiation, trauma or rhinoplasty may add scars, interfere with blood supply, impair healing, and exclude some of the reconstructive options. The operative time, anesthetic requirements, need for hospitalization, number of stages, and the time to completion must be considered and shared with the patient.

THE NOSE

Anatomically, the nose is covered by external skin with a soft tissue layer of subcutaneous fat and facial muscle, supported by a mid-layer of bone and cartilage, and lined by stratified squamous epithelium within the vestibule and mucoperichondrium internally. If missing, each layer must be replaced. Thin, conforming skin cover, shaped mid-layer support, and thin, supple lining are required.

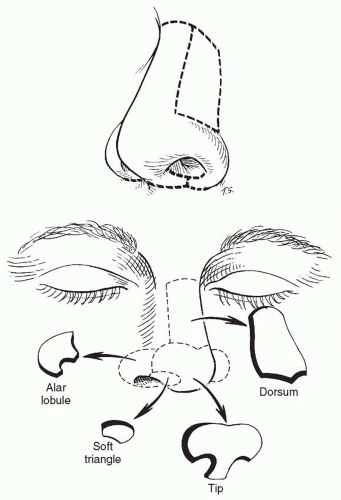

Aesthetically, the nose is a central facial feature of high priority. To appear normal, it must have the proper dimension, volume, position, projection, and symmetry. The surface contour is divided into aesthetic regional subunits–adjacent topographic areas of characteristic skin quality, border outline, and three-dimensional contour: the dorsum, tip, columella, and the paired sidewalls, alae, and soft triangles.3 Restoration of these “expected” visual characteristics must occur to make the nose “appear normal” (Figure 33.1).

The character of nasal skin varies by location. The skin of the dorsum and sidewall (zone 1) is thin, smooth, pliable, and mobile. A small amount of excess skin is present within the upper nose. The skin of the tip and ala (zone 2) is thick, stiff, and adherent, pitted with sebaceous glands. The skin of the columella and alar rim (zone 3) is thin but adherent.

A single-lobe local flap can be efficacious within zone 1, but not within zone 2 or 3. A skin graft can blend satisfactorily within the thin skin of the dorsum and sidewall but may look like a shiny and atrophic patch when used to replace thick tip skin. Traditionally, a local or regional skin flap will blend more accurately within the thick skin of the tip or ala.

Nasal defects can be classified as small and superficial or large and deep. A small, superficial defect is less than 1.5 cm in size, with intact underlying cartilage. A superficial defect over residual, well-vascularized subcutaneous tissue can be skin grafted. However, a skin graft will not take on exposed cartilage or bone without perichondrium or periosteum unless the wound is allowed to granulate to improve the vascular bed. The defect may be resurfaced with a local flap, regardless of vascularity, with more predictable skin quality.

A skin graft adds skin to the nasal surface and can be applied to a defect of any size if its bed is well vascularized. In contrast, local flaps do not add skin to the nose. They rearrange residual skin and redistribute it over the nasal surface. Although a modest amount of excess skin is present within the dorsum and sidewall, no extra skin is available within the tip and ala. Most single-lobe local flaps, because of skin laxity and mobility, can be effectively employed for defects of the dorsum and sidewall, but not for wounds within the thick adherent skin of the inferior nose. No local flap will reach into the infratip or columella. When used inappropriately, local flaps may compromise the underlying residual or repaired cartilage support because of the tension of local skin rearrangement.

A large, deep defect is greater than 1.5 cm or one that requires cartilage grafts for support or lining replacement. If the defect is greater than 1.5 cm, there is often not enough residual skin to spread over the entire nasal surface without distorting the mobile tip or alar rims. A local flap is precluded, although a skin graft may still be employed if its bed is well vascularized. A regional flap from the forehead or cheek will be needed to supply missing skin cover or to vascularize a reconstructed support framework or lining.

FIGURE 33.1. The aesthetic subunits of the nose are determined by the three-dimensional contour of the nasal surface. |

Bones and cartilage support the nose, impart a nasal shape to the soft tissues of both lining and cover, and brace a repair against the force of myofibroblast contraction. If missing, support must be restored.

The normal ala is shaped by compact fibrofatty soft tissue and contains no cartilage. However, if significant external skin or internal lining is missing from the ala, the internal fibrofatty support becomes inadequate. Cartilage must be placed along the new nostril margin to maintain shape and projection, even though the ala normally contains no cartilage.

In the past, bone and cartilage grafts were placed secondarily, months after the initial reconstruction. Unfortunately, once soft tissues are healed, scarring makes secondary re-expansion and reshaping more difficult. In almost all instances, support should be resupplied prior to the completion of wound healing and prior to the pedicle division of regional flaps used for skin coverage.

Soft tissue foreign bodies, such as injectable or implantable allografts, increase the risk of infection, fibrosis, and later extrusion. As a result, nasal reconstruction is usually best performed with autogenous tissues.

THE WOUND

The approach to repair will be influenced by the site, size, depth, and condition of the wound. A fresh wound or healed injury may not reflect the true tissue deficiency. The apparent defect may be enlarged by edema, local anesthesia, gravity, and resting skin tension or diminished by wound contraction due to secondary healing. A prior repair may be distorted by inaccurate tissue replacement–too much or too little. Infection or borderline vascularity may preclude immediate reconstruction.

A preliminary operation may be required to debride necrotic tissue or control infection, or release old scars, replace normal tissue to its normal position, open the airway, or perform preliminary surgical delay, prefabrication, or expansion of the donor site.

Missing tissues must be replaced in exact dimension and outline. If too little tissue is replaced, underlying support grafts collapse under tension and adjacent normal landmarks are dragged inward, distorting the residual landmarks and pushing the lining downward, obstructing the airway. If too much tissue is supplied, adjacent landmarks are pushed outward, distorting the external shape of the nose. The surface area of missing tissue is often underestimated and almost 8 × cm of both lining and cover surface must be supplied in a total nasal defect.

WOUND HEALING

Traditionally, the method of tissue transfer is chosen based on wound vascularity and depth. Skin grafts are used to resurface well-vascularized, superficial defects. Skin flaps are used to supply bulk to a deep defect or to cover a poorly vascularized recipient site, a wound with exposed vital structures, or an exposed or restored support framework or lining.

Unfortunately, the ischemia associated with skin graft “take” leads to unpredictable color and texture match. Even when harvested from traditional facial donor sites (preauricular, postauricular, or submental areas), the quality of a skin graft is unpredictable. Skin grafts often appear shiny and atrophic. Skin grafts are ideally suited to supply thin skin to the dorsum/sidewall or columella/nostril margin, rather than within the thicker skin of the tip and ala where they blend poorly and create a patch-like appearance. A skin graft harvested from the forehead is an exception.

In contrast, a well-healed flap, which maintains its perfusion, retains the skin quality of its donor site. If harvested from a site where the skin quality matches that of the defect, it maintains its characteristics after transfer.

Remember that myofibroblasts lie within a bed of scar between a skin graft or flap and its recipient bed. Although a full-thickness skin graft may shrink minimally within its boundaries, it does not rise above the level of the adjacent recipient skin. In contrast, flaps often “pin cushion,” as the underlying scar contracts. This creates a trapdoor effect that may raise the skin surface of a facial flap into a convex form. For this reason, flaps are best used to resurface convex recipient sites–the tip or ala–as a subunit. Fibroblast contraction under a subunit flap enhances the repair of a convex surface subunit but will distort a repair if the defect lives within the flat sidewall. A skin graft is best for planar or concave recipient sites, such as the dorsum, sidewall, soft triangle, and columella. A subunit flap is best for larger convex tip and alar units.

THE DONOR SITE

Each defect requires variable amounts of cover, support, and lining. Donor materials are chosen by determining the dimension and quality of missing tissues, the available excess within the donor site, and its ability to be transferred as a skin graft over a vascularized bed or a flap on a vascular pedicle with an adequate arc of rotation.

PRINCIPLES OF AESTHETIC NASAL RECONSTRUCTION

Establish a goal. The objective may be a healed wound or the restoration of normal appearance.

Visualize the end result. Normal is described by the skin quality, border outline, and three-dimensional contour.

Create a plan. Specific operative stages, donor materials, and methods of transfer of cover, lining, and support are outlined, prior to the repair. Reconstructive choices will determine the ability to achieve success.

Consider altering the wound in site, size, depth, or position. Most nasal wounds heal with minimal scarring. Scars interfere with a successful reconstruction only when they distort the contour or quality of expected subunits. If a defect of the convex tip or alar subunit is resurfaced with a flap and the wound encompasses greater than 50% of that subunit, consider discarding adjacent normal skin within the subunit. Resurface the entire subunit, rather than just patching the defect. Subunit resurfacing of a convex subunit harnesses the deleterious effects of the trapdoor contraction that occurs under a flap. The pincushioned convexity contributes to the uniform restoration of subunit contour. This is in contrast to the visible “bulge” created by a small flap placed within part of the tip or ala. If residual tissues are distorted by the old scar or a previous repair, normal landmarks must be returned to their normal position at the start of repair.

Use the ideal or the contralateral normal as a guide. A template of the contralateral normal is made to create a mirror image of the true defect or subunit and then used to design flaps and grafts.

Replace missing tissue exactly to avoid overfilling or underfilling of the defect.

Use ideal donor materials. Covering the skin must be thin, conform to the underlying subcutaneous architecture, and match the face in color and texture. Cartilage and bone grafts must be thin, but supportive. The nasal framework must extend from the nasal bone superiorly to the alar

margin inferiorly and from the tip anteriorly to the maxilla posteriorly. Cartilage grafts support the repair against gravity, shape the overlying cover and underlying lining, and brace the repair against scar contraction. Each graft is carved to create a subsurface framework, which will be visible through thin, supple covering skin. Lining materials must be vascular enough to support the early cartilage grafts and supple enough to conform to the shape of the overlying support grafts. Lining must be thin, neither stuffing the airway nor bulging outward, distorting the external shape of the nose.

Ensure a stable platform. The defect may be limited to the nose. However, a composite nasal defect that includes two or more facial units may extend onto the adjacent cheek and lip. The lip and cheek provide the maxillary platform on which the nose sits in specific position and projection. A shifting lip/cheek platform pulls the repaired nose inferiorly and laterally, under the influence of edema, gravity, and tension, distorting an otherwise satisfactory result. Unless the underlying platform is stable, composite defects should be reconstructed in stages. The lip and cheek are repaired during a preliminary procedure. The nose is repaired at a later date.

AN APPROACH TO NASAL RECONSTRUCTION

An appreciation of normal determines the principles of aesthetic reconstruction that restore a normal appearance.1,2 The anatomic loss determines the stages, materials, and methods required to replace missing tissues.

Injury to the nasal platform, lining, support, and covering skin is identified and an operative plan developed. Assessment and surgical repair begins with platform, lining, support, and finally covering skin. This basic approach is modified by training and experience.

The Nasal Base Platform

If the nasal defect extends onto the lip and cheek, the nasal platform must be re-established first.4 If the composite defect is limited to the skin and superficial soft tissues of the cheek and lip, nasal repair can be combined with immediate shifting of the cheek and lip skin flaps for cover and a subcutaneous fat island flap (Gillies/Millard fat flip flap) to supply soft tissue bulk.

Deeper and more extensive composite defects should be repaired in stages, after the completion of wound healing. The nose is repaired only when the facial platform of the lip and cheek is stable after a preliminary operation using major cheek flaps, a cross-lip Abbe flap, or microvascular tissue transfer.

Nasal Lining

The Composite Skin Graft.

Composite skin grafts, taken from the ear, can be used to repair small defects, which include both cover and lining, along the alar margin or columella. They survive if placed on a well-vascularized recipient bed and immobilized. They are best employed for defects not greater than 1.5 cm, which have been allowed to granulate for 7 to 10 days. The color and texture of a composite skin graft are unpredictable and they may appear thin and atrophic over time.

Local Hingeover Lining Flaps.

If a full-thickness defect has been healed, the external skin bordering the defect can be turned over for lining, based on the scar along the border of the full-thickness defect. Such flaps are thick, stiff, and risk necrosis, if greater than 1.5 cm in length. The airway, at the point of the hingeover, is often constricted. Although useful for limited rim defects or in salvage cases, they are unpredictable and are not a first choice in significant defects.

Prelaminated Skin Graft and Cartilage for Lining under a Forehead Flap.

A preliminary operation can be performed several weeks prior to formal nasal reconstruction. A composite graft from the ear or septum or separate pieces of skin and cartilage are placed under the distal end of the planned forehead flap 6 weeks prior to its elevation and transfer to the nose. Once healed to the undersurface of the forehead, these preinstalled lining grafts can create a satisfactory alar margin. However, the reconstructed nose is poorly supported and bulky. The technique is limited to small defects in elderly patients to avoid a more complex procedure.

Intranasal Lining Flaps.

Residual nasal lining remains within the nose and piriform aperture after injury. It is perfused by the anterior ethmoid artery along the dorsum, the angular artery at the alar base, and from branches of the superior labial artery that perfuse the right and left septal mucoperichondrium (Figure 33.2).5,6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree