Perioperative pain control is of increasing importance as awareness regarding the risks of under-controlled pain and opioid abuse rise. Enhanced recovery protocols and multimodal analgesia, including regional blocks, are useful tools for the plastic surgeon. The thoracic paravertebral block, pectoralis nerve I and pectoralis nerve II blocks, and proximal intercostal blocks are 3 described methods that provide regional anesthesia for breast surgery. The widespread use of these methods may be limited by the requirements for ultrasound equipment and anesthesiologists skilled in regional blocks. This article describes a novel technique of the intercostal field block under direct visualization that is safe and efficient.

Key points

- •

Opioid-free initiatives are of increasing importance in perioperative pain management.

- •

Several regional blocks have been successfully described for use in breast surgery, including paravertebral, pectoralis nerve I and II, serratus, and intercostal blocks.

- •

Intercostal field blocks performed under direct visualization are an effective means of reducing opioid consumption in cosmetic breast surgery patients without the need for special equipment or additional surgical time.

Introduction

Perioperative pain control is a topic of increasing importance in today’s medical climate. Under-controlled pain is related to prolonged hospital admissions, increased readmissions, higher risk of persistent postsurgical pain, and decreased patient satisfaction. At the same time, concerns over opioid misuse are rising, challenging traditional pain management strategies. Enhanced recovery protocols and multimodal analgesia alternatives are being implemented in many surgical fields and plastic surgery is no exception. Regional blocks are a valuable tool with multiple indications. In breast surgery, multiple regional blocks have been described as adjuvants or alternatives to opioid anesthetics. This article reviews current methods and describes a novel approach to perform intercostal field blocks safely under direct visualization for aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery.

Background

Opioid Overuse

The economic and social impacts of the opioid epidemic are staggering. In 2018 alone, opioids were involved in 46,802 overdose deaths, which accounts for 69.5% of all overdose deaths. The rapid rise in overdose deaths in the past 2 decades coincides with the expansion of opioid prescribing for pain control in the 1990s. Deaths related to prescription opioids were more than 4 times higher in 2018 compared with 1999. Estimates of the economic consequences of the opioid epidemic surpass $95 billion per year.

Plastic surgery is not spared from this crisis. Recent studies reveal that plastic surgeons performing outpatient procedures often prescribe almost double the amount of opioids that are consumed by patients postoperatively. Excessive prescribing can set up patients for unintentional overdose or diversion of unused pills, with documented incidences of both nonfatal and fatal prescription-related opioid overdoses in the plastic surgery literature. , Even when used appropriately, reliance on opioids for pain control has significant side effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, pruritis, and respiratory depression.

Enhanced Recovery Protocols

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways increasingly are advocated as multidisciplinary, multimodal tools to reduce hospital length of stay, decrease total costs, reduce postoperative morbidity, and, importantly, reduce opioid consumption. , For breast reconstruction surgery, consensus guidelines from the ERAS Society outline 18 elements of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care for optimization, including recommendations for multimodal management of preoperative and postoperative pain control. Such measures have demonstrated efficacy in reducing hospital stay, decreasing opioid use, and enhancing patient experience for both autologous and implant-based breast reconstruction patients. Although there is little literature describing ERAS protocols for cosmetic breast surgery, the principals outlined by efforts in reconstructive breast surgery provide a valuable framework for enhancing patient care for these cases. Ambulatory breast procedures, in particular, where patients have limited postoperative supervision, could benefit from ERAS protocol implementation.

Regional Blocks

Local anesthesia has a long tradition of utility in plastic surgery. The most common anesthetic agents are lidocaine and bupivacaine, either plain or in mixture with epinephrine, to reduce bleeding and to prolong the duration of efficacy. Frequently used for pain control in emergency room and clinic procedures, innovative methods with local injections led to the advent of wide-awake plastic surgery. This development eliminates the risks of sedation or general anesthesia for many patients undergoing cases traditionally performed in the operating room.

The introduction of liposomal bupivacaine expands on these benefits. Bupivacaine in this formulation diffuses from within a lipid-based vehicle over the course of 48 hours to 72 hours, providing long-lasting pain relief. Either bupivacaine with epinephrine or liposomal bupivacaine can be administered as a regional block. Although the Food and Drug Administration differentiates blocks from local infiltration, the concept is the same: infiltration of local anesthetic into a targeted area to affect a specific nerve or group of peripheral nerves in order to provide anesthesia to a specific dermatome. These blocks are useful for the plastic and reconstructive surgeon. For example, multiple studies have demonstrated the utility of the transverse abdominus plane block in reducing postoperative pain in both abdominal wall reconstruction and cosmetic abdominoplasty patients.

Several regional blocks have been described to reduce pain during breast surgery. The sensory innervation of the breast consists of 3 components: medial innervation from the anterior cutaneous branches of intercostal nerves I to VI, lateral innervation from the lateral cutaneous branches of intercostal nerves II to VII, and superior innervation from the supraclavicular nerves. Regional blocks for breast surgery target these end nerves.

Paravertebral Block

In the thoracic paravertebral (TPV) block, local anesthetic is injected into the space where the thoracic spinal nerves emerge from the intervertebral foramina, immediately lateral to the intervertebral foramina. Anatomically, the TPV space is defined anteriorly by the parietal pleura, posteriorly by the superior costotransverse ligament, medially by the vertebrae, and superiorly and inferiorly by the ribs. Because this affects the spinal root and sympathetic chain, the TPV block acts as a sensory, motor, and sympathetic block within multiple dermatomes.

Studies demonstrate that breast reconstruction patients who undergo a TPV block experience reduced pain and reduced opioid consumption as well as less nausea and vomiting, compared with patient managed with general anesthesia alone. Complications of TPV block include hypotension, vascular puncture, pneumothorax, and epidural spread. With increasing body mass index, the probability of block failure increases, limiting the patient population for whom TPV block is indicated. Given the potential complications, it is recommended that TPV blocks be administered only by experienced anesthesiologists under ultrasound supervision.

Pectoralis Nerve I and II Blocks

The pectoralis nerve (PECS) I block involves infiltration of local anesthetic into the interfascial plane between the pectoralis major and minor muscles, anesthetizing multiple branches of the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. This motor blockade acts to relax the pectoralis muscle fibers, thus alleviating pain associated with muscle tension and spasm. This modality is limited in that it does not provide significant sensory blockade.

The PECS II block adds to the PEC I with infiltration above the serratus anterior muscle at the level of the third rib, with the intention of blunting the intercostobrachial, long thoracic, pectoral, and intercostal nerves III to VI. The addition of the PECS II block has been shown to reduce postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting in breast surgery patients compared with general anesthesia alone. This method also is performed under ultrasound guidance. Complications include risk of intravascular injection, pneumothorax, and winged scapula. , Additionally, although effective for intercostal nerves III to IV, it seems to be less reliable for levels V to VI (L.I., senior author observation).

Proximal Intercostal Block

Proximal intercostal (PIC) nerve blocks have been described for various breast surgery indications as well as for pain control during thoracic procedures. , Under ultrasound guidance, local anesthetic is injected into the second and fourth intercostal spaces, providing sensory block to the intercostal nerves. Breast surgery patients who underwent PIC blocks had lower opioid consumption compared with general anesthesia alone and, in 1 study, patients were able to undergo breast surgery with PIC block and sedation alone, reducing the risks associated with general anesthesia. Hypothetical risks include vascular puncture and pneumothorax.

Limitations

Although regional blocks have demonstrated promising improvement in patient care and specifically reduction of postoperative pain and opioid use, there are limitations to their use, especially in the ambulatory surgery and office-based settings, where aesthetic procedures are performed most commonly. The TPV block, PECS I and II blocks, and PIC blocks all require the presence of an anesthesiologist trained in regional anesthesia as well as availability of ultrasound equipment. These procedures require additional time in either the preoperative area or in the operating room. Risks of intravascular injection and pneumothorax also may limit use of these blocks in the hands of an inexperienced provider.

Techniques

Given the success of regional blocks but faced with the limitations of application in the ambulatory setting, the authors have developed a reliable and reproducible technique for intercostal field block under direct visualization that does not require any special or additional equipment and adds virtually no additional time to the surgical procedure.

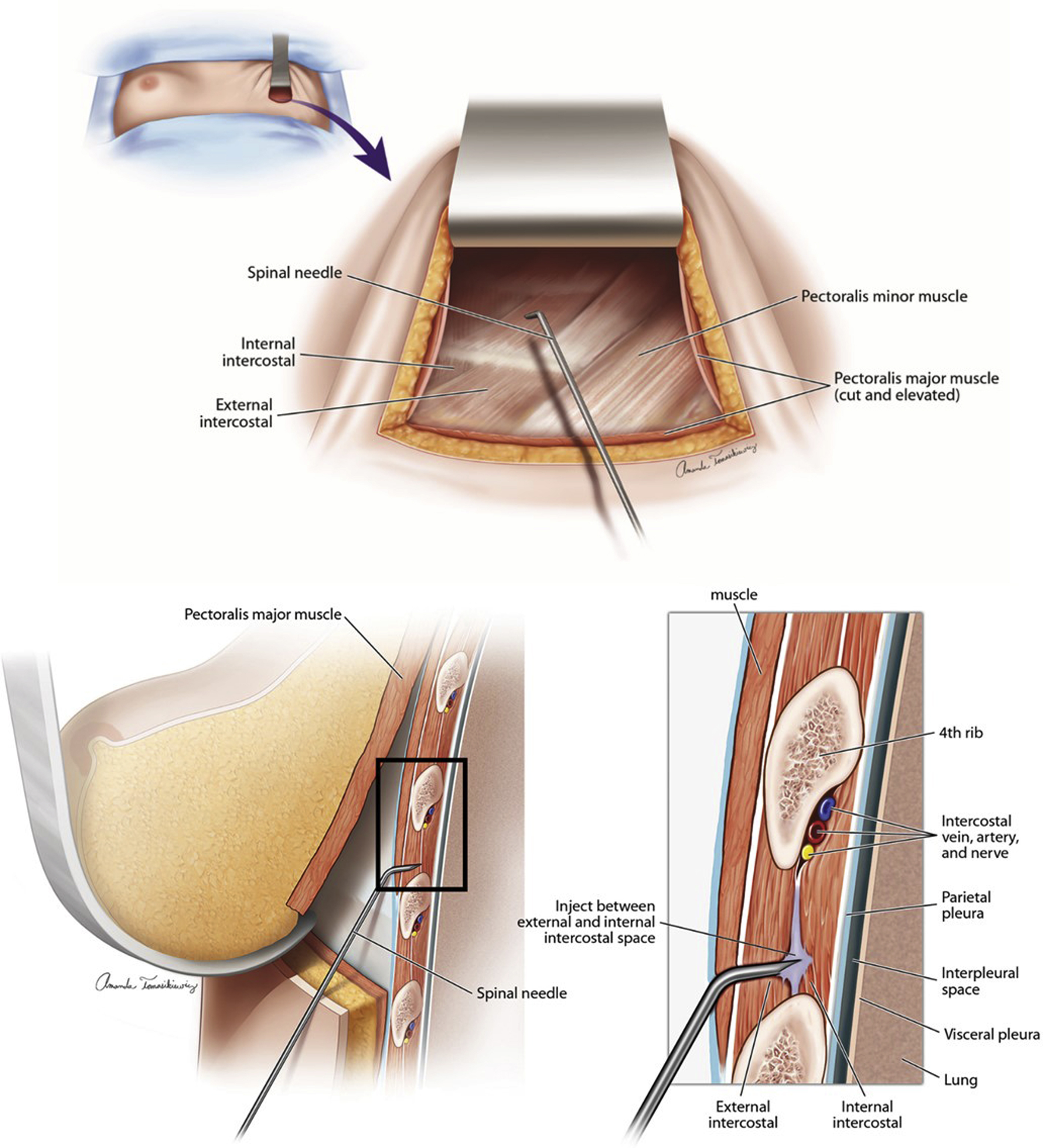

The intercostal neurovascular bundle is located caudal to its named rib, between the external and internal intercostal muscles. To achieve the desired anesthetic effect, this space is cannulated and injected with a local anesthetic of choice. For procedures with less discomfort, such as a mastectomy, bupivacaine with epinephrine usually is adequate. The authors have found that breast augmentation, augmentation mastopexy, breast reconstruction, and breast reduction benefit from a longer duration of action and favor the use of liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel, Pacira Biosciences, Inc., Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ).

Accessing the intercostal space is performed using an angled spinal needle to control the depth of penetration ( Fig. 1 ). In order to maintain adequate internal luminal diameter for use with liposomal bupivacaine, a 22G (gauge) spinal needle typically is used. The authors create a bend of 45° by grasping the needle with the end of an Olsen-Hegar needle holder just proximal to the bevel ( Fig. 2 ). This creates an angled segment approximately 7 mm in length with a depth of penetration of 5 mm. Because the average rib is 7-mm to 11-mm thick, there is a very low risk of penetrating the pleura.