Miscellaneous Bacterial Infections with Cutaneous Manifestations: Introduction

This chapter focuses on a group of unrelated bacterial diseases that are rarely encountered in a conventional urban or suburban setting but are acquired after a distinctive environmental exposure, such as saltwater immersion, animal bites, handling of an infected animal carcass, or travel to specific areas around the world. Several of these diseases present primarily as cutaneous disorders with rare systemic involvement (e.g., erysipeloid); others present primarily as systemic disorders with rare cutaneous involvement (e.g., brucellosis). Several of the pathogens can be aerosolized and disseminated for respiratory transmission, naturally or with human intervention. The ease of dissemination and the potential virulence of several organisms make them suitable for intentional spread as biologic weapons. The intentional spread of these diseases is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 213.

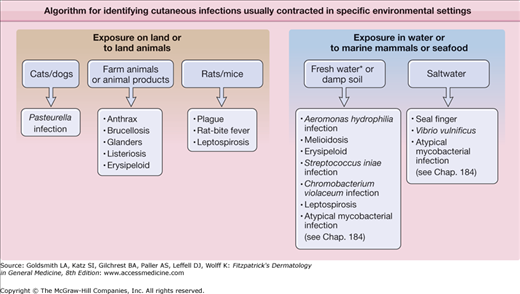

In this chapter, these infections are grouped by their most common, natural means of transmission to humans: atraumatic exposure to animals, animal bites, and contact with contaminated water (Fig. 183-1).

Anthrax

|

Anthrax is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, a large aerobic, spore-forming Gram-positive rod.1 Anthrax occurs naturally in ruminant mammals, such as sheep, cattle, and goats. Human disease is seen most often in agrarian, livestock-dependent regions. Consequently, human anthrax usually follows agricultural or industrial exposure, either through direct handling of infected animals or contaminated soil or through the processing of hides, wool, hair, or meat.2 Anthrax has potential as a class A bioweapon (Table 183-1; see also Chapter 213).

Infection | Expected Demographic Distribution | Typical Presentation (Skin)a | Typical Exposure | Bioweapon Potentialb | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anthrax | Worldwide, especially developing agrarian areas | Painless edematous plaque with central black ulcer or eschar | Goats, sheep, cattle, or products made from them | A | PCN, doxycycline, ciprofloxacin |

Tularemia | North America, Europe | Ulceroglandular: painful papule that ulcerates and forms eschar | Tick bites, rabbits, rodents | A | Aminoglycoside, fluoroquinolone, doxycycline. |

Plague | Worldwide, especially United States Southwest, India | Buboes (tender regional lymphadenopathy) followed by purpura and gangrene | Flea bites, spread from infected rodents | A | Aminoglycoside, doxycycline, cotrimoxazole |

Brucellosis | Worldwide, especially developing agrarian areas | Variable; skin manifestations present in <5% of patients | Cattle, sheep, goats, or untreated milk | B | Doxycycline plus aminoglycoside or rifampin |

Glanders | Rare and focal in Asia, Middle East | Nodule with cellulitis that ulcerates; later, deep abscesses and sinuses | Donkeys, mules, horses | B | Sulfadiazine, gentamycine, doxycycline |

Pasteurella infection | Worldwide | Rapid onset of cellulitis at bite site followed by necrosis | Dog or cat bite | NR | Amoxicillin plus CA |

Rat-bite fever (streptobacillary) | Worldwide, especially Asia | Morbilliform eruption with fever followed by arthritis | Rats or their excreta | NR | Amoxicillin plus CA |

Seal finger | Cool coastal regions worldwide | Extremely painful nodule on finger | Seals or sea lions | NR | TCN, ceftriaxone |

Listeriosis | Worldwide | In neonates, generalized petechiae, papules, and pustules | In neonates, infected mother with transfer in utero or shortly after birth | NR | Ampicillin or PCN IV |

Vibrio vulnificus infection | Worldwide | Necrotizing fasciitis, hemorrhagic bullae often beginning as a wound infection | Warm saltwater or brackish water or undercooked seafood | NR | Doxy and ceftazidime IV, debridement of lesions |

Aeromonas hydrophila infection | Worldwide | Cellulitis evolving to abscess formation, often beginning as a wound infection | Fresh or brackish water, contaminated fish | NR | Third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones; debridement |

Melioidosis | Wet tropical areas, especially Southeast Asia and northern Australia | Indolent abscesses; suppurative parotitis (in children) | Wet soil (classically rice paddies), flooded regions | B | Ceftazidime plus a carbipenem IV, then prolonged oral amoxicillin CA or TMP-SMX |

Erysipeloid | Worldwide | Tender violaceous plaque on hand at site of injury | Contaminated fish, shellfish, poultry, meat, and animal products | NR | PCN, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolone |

Streptococcus iniae infection | Worldwide, especially freshwater fish farms | Rapid onset of hand cellulitis following a puncture wound | Contaminated farm-raised fish | NR | PCN, cephalosporin |

Leptospirosis | Worldwide, especially the tropics | Papules, petechiae, jaundice | Contaminated freshwater, moist soil, or animal urine | NR | Doxy, PCN |

Diphtheria | Worldwide where immunization is not practiced | Pustule or superinfected abrasion, evolving to an ulcer with gray membrane at base | Asymptomatic human carriers | NR | PCN IV or erythromycin plus antitoxin |

The clinical presentation of human anthrax depends on the route of inoculation. In 95% of human cases, the disease is acquired through percutaneous inoculation of anthrax spores. Human anthrax can also be acquired as inhalational and gastrointestinal disease. Recent cases in the United States of both forms have been associated with recreational use of drums made of unprocessed animal hides imported from West Africa.3,4 Each of anthrax’s form has distinctive clinical, epidemiologic, and prognostic features.5

Outbreaks still occur in endemic areas.6–11 During the late twentieth century, thousands of people in the African nations of Zambia and Zimbabwe developed anthrax.12 More than 90% of cases were cutaneous and the remainder represented an equal mix of inhalational and gastrointestinal disease. Dying animals typically release vegetative bacilli into the environment, which then convert into the dormant, yet infectious, spores. There are ongoing outbreaks of animal anthrax among free-ranging wood bison (Athabaskan buffalo) in Northern Canada,13 several species of antelope in Zambia,14 hippopotami in Uganda, and domesticated grazing animals in North Dakota.15

After an incubation period of 1–7 days, patients may experience low-grade fever and malaise and develop a painless papule at the exposed site. As the lesion enlarges, the surrounding skin becomes increasingly edematous. Pain, if present, is usually due to edema-associated pressure or secondary infection.

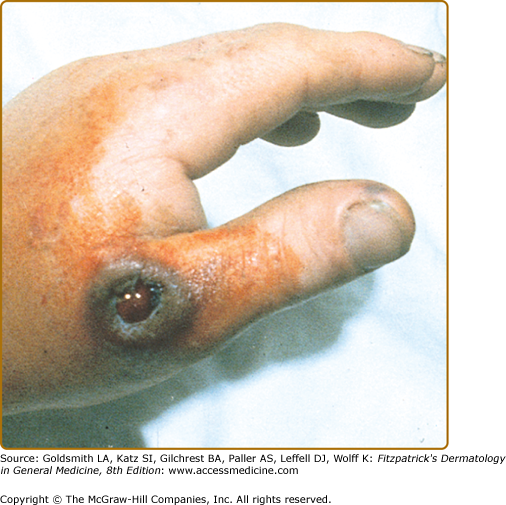

Cutaneous anthrax develops when spores enter minor breaks in the skin, especially on exposed parts of the hands, legs, and face (Fig. 183-2). In the hospitable environment of human skin, spores revert to their rod forms and produce their toxins. A dermal papule, often resembling an arthropod bite reaction, develops over several days, and then progresses through vesicular, pustular, and escharotic phases. Lesions are surrounded by varying degrees of edema. Depending on the manner of inoculation, one to several lesions may appear, and there may be regional lymphadenitis, malaise, and fever. Individual lesions may appear pustular, leading to the name “malignant pustule,” but they do not suppurate. In anthrax, true pustules are rare; a primary pustular lesion is unlikely to be cutaneous anthrax.

Figure 183-2

Anthrax. The classic cutaneous lesion of a primary infection in anthrax is a painless papule that evolves into a hemorrhagic bulla with surrounding brawny nonpitting edema. Note the typical localization on the hand. The name anthrax comes from the Greek word ανθραξ (anthrax), meaning coal, which refers to the coal-black hue of the lesions of cutaneous anthrax.

The lesion enlarges into a glistening pseudobulla that becomes hemorrhagic with central necrosis and may be umbilicated (see Fig. 183-2). The necrotic ulcer is usually painless, which is an important feature in differentiating it from a brown recluse spider bite. There may be small satellite papules and vesicles that may extend along lymphatics in a sporotrichoid manner. An area of brawny, nonpitting edema (“malignant edema”) often surrounds the main lesion. Lesional progression is due to toxins and is unaffected by antibiotic therapy. Fatigue, fever, chills, and tender regional adenopathy may cause an ulceroglandular syndrome. The eschar dries and separates in 1–2 weeks.16–20

Cutaneous anthrax may cause fever, tachycardia, and hypotension.

The prominent features are hemorrhagic edema, dilated lymphatics, and epidermal necrosis. Bacilli may be found in the eschar. Anthrax is toxin-mediated and induces scant inflammatory infiltrate. Immunohistochemical stains are quite useful.21

Naturally occurring anthrax is treated with penicillin or doxycycline. Weaponized anthrax, on the other hand, may be resistant to these antibiotics, and, therefore, a fluoroquinolone is recommended for the initial treatment of confirmed or suspected bioterrorism-associated anthrax, even in pregnant women and children. Once drug sensitivities have been established, the patient may be switched to another antibiotic as clinically indicated. Antibiotics will kill activated B. anthracis bacilli but will not alter tissue damage already caused by toxins.22,23 To neutralize the anthrax toxins, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now possesses human antianthrax immunoglobulin and monoclonal antibodies directed against the toxins are in development.

Although cutaneous anthrax is usually an uncomplicated and readily treatable infection, public health concerns warrant hospitalization. Standard universal precautions are appropriate but specific measures against secondary respiratory transmission are unnecessary because anthrax is not transmitted from person-to-person.

Parenteral crystalline penicillin G (2 million units every 6 hours) was the treatment of choice prior to the 2001 bioterrorism outbreak. In one study, smears and cultures from vesicles or from the necrotic tissue beneath the eschar became negative within 6 hours of initiation of penicillin therapy. Treatment of primary cutaneous anthrax is continued with parenteral therapy until the local edema disappears or the lesion dries up over 1–2 weeks. When the edema resolves, the patient may complete the 60-day treatment with oral therapy.

Other than to obtain material for culture or histopathology, incision and debridement of the cutaneous lesion is unnecessary. First of all, the lesions contain no purulent material needing evacuation and, second, without effective antibiotics, these procedures increase the risk of bacteremic spread of the disease.

Untreated cutaneous anthrax, particularly if nonedematous, is a largely self-resolving disease. In contrast, some lesions, especially ones with massive edema, pose the risk of bacteremia with subsequent septicemia. Thus, the mortality rate of untreated cutaneous anthrax is roughly 5%–20%. With prompt and appropriate antibiotics, there is rapid defervescence and clinical improvement. Massive facial edema associated with cutaneous lesions of the head or neck may lead to respiratory compromise, requiring intubation or tracheostomy and systemic corticosteroids. Palpebral lesions may scar the eyelids and edema-associated seventh-nerve palsy may occur.24 Hospitalization in an intensive care unit is recommended for any patient with inhalational or gastrointestinal anthrax.

In nonendemic areas, any case of anthrax requires immediate reporting to public health authorities and a prompt public health response because of the threat of intentional criminal or terroristic release. Although anthrax is a dangerous disease, it is not transmitted from person-to-person. Instead, the spore is the infectious propagule. Therefore patients with anthrax—of whatever clinical presentation—do not require isolation.

An anthrax vaccine has been in use since 1954 for people with occupational exposure to natural anthrax (e.g., veterinarians, wildlife biologists). The CDC recently released new guidelines on its use in the post-9/11 era for routine occupational use and for pre- and postoutbreak exposure use.25

Although cutaneous anthrax is usually an uncomplicated and readily treatable infection, public health concerns warrant hospitalization. Standard universal precautions are appropriate but specific measures against secondary respiratory transmission are unnecessary because anthrax is not transmitted from person-to-person.

Tularemia (Francisella Tularensis Infections)

|

Tularemia is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by Francisella tularensis, a pleomorphic Gram-negative coccobacillus found in many species of mammals, most important, lagomorphs (rabbits and hares) and rodents, and in their immediate environments. The bacteria are highly infectious, can be transmitted in many ways, and cause at least eight different patterns of disease.

Tularemia occurs solely in temperate and cold regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The most common form in the United States is ulceroglandular disease in which organisms are inoculated directly into the skin by minor trauma or by bites of infected arthropods that maintain the enzootic cycle. Before 1950, most US infections occurred in hunters who handled infected rabbits and hares. Two incidence peaks each year corresponded with summer and winter hunting seasons. Currently, 100–150 US cases occur each year, mostly in Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma, with transmission of the organism largely via tick bites. The most common tick vectors are Dermacentor variabilis, Amblyomma americanum, and, in Europe, Ixodes sp.26–30

Of several subspecies, the most virulent (F. tularensi subspecies tularensis) lives only in the North America. A more benign one (F. tularensis subspecies holarctica) is the only subspecies in Eurasia. Although these bacteria do not produce spores, they can survive environmentally—and maintain infectivity—for months.28,29

Tularemia is transmitted in other ways, too. Other arthropod vectors include the deerfly (Chrysops discalis) in the Western United States, and mosquitoes in Scandinavia and the Baltic region.31 An outbreak of pulmonary tularemia on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, was associated with springtime mowing of tall grass.32 The precise environmental source was not clear, perhaps aerosolization of animal excreta in the grass. Domestic cats may spread the organism via direct contact, bite, or aerosol. In parts of Europe, aquatic rodents (muskrats and beavers), household rodents, and drinking water contaminated by these animals are the major sources of infection. Rarely, direct inoculation into conjunctivae or ingestion of poorly cooked, contaminated meat causes infection. There is no human-to-human transmission. A second species, Francisella philomiragia, can infect patients with inherited defects in phagocytosis such as chronic granulomatous disease (OMIM #306400).

Duration of incubation varies with size of inoculum, ranging from 2–10 days. All forms of tularemia present as a sudden flu-like illness characterized by fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias.

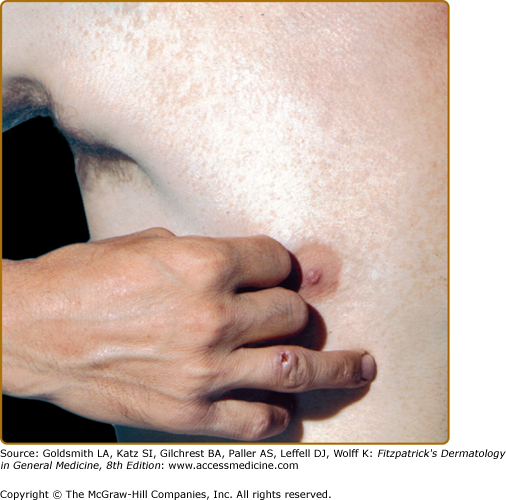

In ulceroglandular tularemia, a painful red papule appears at the inoculation site (Fig. 183-3). It enlarges rapidly and evolves into a necrotic chancriform ulcer often covered by a black eschar. Regional lymph nodes are large and tender.32 Bacteremia may cause sepsis and virulent pneumonia. In two recent Scandinavian outbreaks with the less virulent holarctica type of tularemia, due primarily to mosquito-borne ulceroglandular disease, approximately one-third of nearly 300 patients developed nonspecific secondary cutaneous manifestations, such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, or an asymptomatic id-like papular eruption on the extremities.31,33

In oculoglandular tularemia, organisms are introduced directly into the conjunctivae, for example, after handling an infected tick or rabbit. This causes purulent conjunctivitis with pain, edema, and local adenopathy. In a recent outbreak in Bulgaria, more than 90% of cases were oropharyngeal, reflecting transmission via contaminated well water. Swallowing the organism may cause ulcerative pharyngotonsillitis with cervical adenopathy or may cause “typhoidal” tularemia.34 Pulmonary tularemia may be primary (i.e., due to inhalation of organisms) but is more often because of bacteremic spread from another focus.

Laboratories should be notified of suspected tularemia so that cultures can be set under biohazard conditions to avoid aerosolization. F. tularensis grows best on cysteine-supplemented blood agar, producing nonmotile, nonsporulating, pleomorphic, Gram-negative coccobacilli. Some reference laboratories also use animal inoculation techniques.

The pathogen survives intracellularly in phagocytes, and small granulomas develop in lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. Some lesions may caseate and progress to frank abscess formation. Hepatic granulomas may resemble tuberculosis or brucellosis.

The primary lesion of tick-transmitted tularemia resembles a furuncle, paronychia, common ecthyma, the initial lesion of anthrax, Pasteurella multocida infection, or sporotrichosis. Prominent regional adenopathy may suggest cat-scratch disease, plague, or melioidosis. Fever after a tick bite might suggest Rocky Mountain spotted fever, but that usually has an exanthem rather than a chancriform lesion. Other tick-borne febrile diseases include other rickettsioses, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, and viral tick fevers. F. tularensis is difficult to grow so the diagnosis is usually made by serologic tests showing a rise in titers. Although the subspecies of F. tularensis are clinically and epidemiologically distinct, they are serologically indistinguishable.28

A presumptive diagnosis of tularemia on clinical and epidemiologic grounds is sufficient to initiate treatment while awaiting serologic confirmation (see Table 183-1). Treatment consists of an aminoglycoside antibiotic, such as gentamicin, or a fluoroquinolone; these should be given for at least 10 days. A tetracycline antibiotic, such as doxycycline, given for at least 15 days is an acceptable alternative. Patients improve within 24–48 hours, but treatment should continue for at least 7–10 afebrile days to reduce the risk of relapse.

Untreated pulmonary and typhoidal tularemia have mortality rates of about 30%. Without antibiotics, ulceroglandular disease lasts many weeks and has a mortality rate of 5%. Brief courses of antibiotics may permit relapse but, with proper treatment, uncomplicated recovery is expected.

Hunters and animal handlers should wear impervious gloves when handling game, especially rabbits. Game meat should be cooked thoroughly, even if stored frozen for long periods. A live-attenuated (but rarely used) vaccine was developed in Russia; the US government is currently funding vaccine research. The disease is reportable in the United States and any cluster of pulmonary tularemia cases should raise concerns of bioterrorism.29,35

Plague

|

Plague is a severe, acute, febrile zoonosis caused by the aerobic Gram-negative bacillus Yersinia pestis. Plague exists in an enzootic cycle, infecting humans through contact with rodent reservoirs or flea vectors. Human plague has three clinical forms: (1) bubonic; (2) bubonic septicemic, a more virulent form due to secondary bacteremia and sepsis; and (3) pneumonic (fulminant disease due to respiratory spread). Distal purpura and gangrene associated with septicemic plague likely gave rise to the term black death. The plague bacillus likely evolved from the fecal–oral pathogen, Y pseudotuberculosis, by acquiring several virulence plasmids.36

Endemic or sylvatic plague occurs in wild rodents in the Western United States, parts of South America, much of sub-Saharan Africa, and across Southern Asia. In most places, plague is sporadic but Madagascar currently has epidemic plague.37,38 There are several thousand cases of plague worldwide each year and the disease prevalence is increasing across Africa; Madagascar alone account for nearly half the number of human cases each year.36,39

In this country, human disease is almost always transmitted by fleas. Direct handling of infected rodents, rabbits, or their carcasses can also transmit plague. Some cases are transmitted by direct contact with pet dogs or cats that become ill after contact with infected wild animals. Between 1990 and 2005, 107 plague cases, more than 80% bubonic, were reported in the United States, averaging seven per year, mostly in summertime. In Western States, winter cases are often linked with handling of animal carcasses while hunting. In recent years, epizootics have occurred among prairie dogs, and sporadic human cases were seen on several Indian reservations, associated with ground squirrels. Rarely, bacteremic bubonic disease may evolve into pneumonic plague and further initiate respiratory spread to others.40,41

The flea associated with epidemic plague in the Old World is Xenopsylla cheopis, but fleas in other genera (e.g., Anomiopsyllus, Aetheca, Pulex) are also vectors in the United States.

Because Y. pestis can be aerosolized, is devastatingly lethal, and can spread from person-to-person, it is considered a Category A biologic weapon (see Table 183-1). Y. pestis produces an intracellular toxin and virulence factors (see Chapter 213).

Bubonic plague incubates for roughly 2–6 days, followed by the sudden onset of high fever, prostration, malaise, myalgias, backache, and tachycardia. Primary pneumonic plague has a shorter incubation time.

In bubonic plague, the initial skin lesion is related to the fleabite and may appear as papular urticaria. However, the hallmark of bubonic plague is prominent, exquisitely tender regional lymphadenopathy with extensive subcutaneous edema. Inguinal buboes are most common in adults; cervical and axillary buboes are more common in children.36

Any form of plague can lead to overwhelming endotoxic septicemia accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) (see Chapter 144 and 181). Subsequent purpura and gangrene are most severe on distal extremities.42

Primary septicemic plague lacks buboes and presents with typical Gram-negative sepsis. Many patients also have severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. Pneumonic plague has an abrupt onset with high fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, chest pain, and dyspnea. Within 24 hours of onset, the patient is critically ill and producing bloody sputum laden with Y. pestis. Meningitis may complicate all forms of plague.

![]() In bubonic plague, organisms can be cultured from lymph node aspirates and blood; in pneumonic plague, sputum, or tracheal washes. Lymph node aspirates are obtained by using a sterile syringe to inject 1 mL of saline into the center of a bubo and withdrawing purulent material until the pus is tinged with blood. Special transport medium (e.g., Cary-Blair medium) is helpful but the culture may be performed in standard brain-heart nutrient broth. The organisms appear as Gram-negative coccobacilli with a Gram stain but their bipolar bacillary appearance is more distinctive with Wright–Giemsa or Wayson stains.36,43 Bacilli can sometimes be seen on stained buffy coat smears. Leukocytosis occurs in all forms of the disease. Renal failure and DIC may occur in severe cases. Bacteria can be cultured on standard blood agar media. Direct fluorescent antibody assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and polymerase chain reaction testing are useful when available, but serologic tests are less reliable.42,44 Histopathologically, acute inflammatory changes are seen in the involved nodes. Immunohistochemical stains of tissue biopsy specimens may show organisms.45

In bubonic plague, organisms can be cultured from lymph node aspirates and blood; in pneumonic plague, sputum, or tracheal washes. Lymph node aspirates are obtained by using a sterile syringe to inject 1 mL of saline into the center of a bubo and withdrawing purulent material until the pus is tinged with blood. Special transport medium (e.g., Cary-Blair medium) is helpful but the culture may be performed in standard brain-heart nutrient broth. The organisms appear as Gram-negative coccobacilli with a Gram stain but their bipolar bacillary appearance is more distinctive with Wright–Giemsa or Wayson stains.36,43 Bacilli can sometimes be seen on stained buffy coat smears. Leukocytosis occurs in all forms of the disease. Renal failure and DIC may occur in severe cases. Bacteria can be cultured on standard blood agar media. Direct fluorescent antibody assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and polymerase chain reaction testing are useful when available, but serologic tests are less reliable.42,44 Histopathologically, acute inflammatory changes are seen in the involved nodes. Immunohistochemical stains of tissue biopsy specimens may show organisms.45

Most patients with bubonic plague present with the rapid onset of a toxic febrile illness, painful buboes, and evidence of an arthropod bite without surrounding cellulitis. Bubonic plague should be distinguished from tularemia, lymphogranuloma venereum, cat-scratch disease, chancroid, Kikuchi’s disease, and suppurative lymphadenitis due to staphylococcal or streptococcal infections. Pneumonic plague must be differentiated from other acute bacterial pneumonias. Epidemiologic considerations and the tempo of the illness are major points in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis is made by examining Gram-stained (or specific fluorescent antibody stained) smears of infected material or by culturing organism from blood, sputum, or aspirated buboes. Serologic methods help retrospectively by demonstrating a fourfold or greater rise in titers. A convalescent passive hemagglutination titer of >1:16 suggests the diagnosis.

Because the original drug of choice, streptomycin, is not widely available, another aminoglycoside antibiotic, gentamicin, is the preferred treatment (although the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved it for this indication) (see Table 183-1). Doxycycline is also effective and maybe the treatment of choice when oral therapy is required or to use as postexposure prophylaxis. Cotrimoxazole is useful when combination therapy is desired.43 Patients with pneumonic plague must be placed in respiratory isolation to prevent further transmission. The course of treatment, irrespective of medication, is 10 days. Ordinarily, buboes should not be drained until they are well-localized and antibiotic therapy has been started.46

Pneumonic and septicemic plague, if untreated, are nearly always fatal. Untreated bubonic plague has a mortality rate of roughly 50% but early antibiotic therapy has reduced this to 5%–10%. Because primary septicemic plague lacks telltale buboes, the clinical suspicion of plague is often delayed, hence antibiotics are started late and mortality is high.

Most cases in the United States are acquired peridomestically so it is important in endemic areas to control rodents around homes. Children should be taught to avoid rodent nests, burrows, and dead animals. Pets should be given regular flea treatments, examined properly when ill, and trained not to hunt small mammals or eat sick or dead mammals. Rabbit hunters should wear gloves when handling carcasses. With pneumonic cases, respiratory isolation is mandatory and close contacts should receive antibiotic prophylaxis with doxycycline or cotrimoxazole. Plague vaccine is no longer available. Because the disease is a zoonosis, it is considered ineradicable, so prevention through rodent control is the most important way to prevent plague.36,39

Brucellosis

|

![]() Brucellosis is caused by any of four species of Brucella, which ordinarily infect livestock, especially cattle, sheep, and goats. It is transmitted to humans by contact with infected animals or animal products, ingestion of unpasteurized or contaminated dairy products, and, rarely, by inhalation of aerosolized bacteria. Worldwide there are approximately 500,000 human cases per year. The highest incidence is in underdeveloped agrarian areas where there are poor health controls for herds, where people consume raw dairy products, and the populations are nomadic with less access to medical care. These regions include East Africa, grazing areas of upland South and Central America, and the belt of nations extending from Spain and Portugal across the Mediterranean basin, through Asia from Turkey and the Middle East, and across the former Soviet republics to Mongolia. Domesticated animals are reservoirs for Brucella, and the two species that most commonly infect humans are Brucella melitensis (“from Malta,” where the disease was first described) and Brucella abortus, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis are less common pathogens.47–51

Brucellosis is caused by any of four species of Brucella, which ordinarily infect livestock, especially cattle, sheep, and goats. It is transmitted to humans by contact with infected animals or animal products, ingestion of unpasteurized or contaminated dairy products, and, rarely, by inhalation of aerosolized bacteria. Worldwide there are approximately 500,000 human cases per year. The highest incidence is in underdeveloped agrarian areas where there are poor health controls for herds, where people consume raw dairy products, and the populations are nomadic with less access to medical care. These regions include East Africa, grazing areas of upland South and Central America, and the belt of nations extending from Spain and Portugal across the Mediterranean basin, through Asia from Turkey and the Middle East, and across the former Soviet republics to Mongolia. Domesticated animals are reservoirs for Brucella, and the two species that most commonly infect humans are Brucella melitensis (“from Malta,” where the disease was first described) and Brucella abortus, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis are less common pathogens.47–51

![]() In the United States, brucellosis has largely been eliminated by proper animal husbandry practices. Still, there are 100–200 cases annually, mostly in travelers who ate raw dairy products in endemic areas or in people who consume illegally imported unpasteurized Mexican dairy products. Those at high risk include herders, farmers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers. Hunters who handle carcasses of large game such as deer, elk, and wild pigs are also at risk.

In the United States, brucellosis has largely been eliminated by proper animal husbandry practices. Still, there are 100–200 cases annually, mostly in travelers who ate raw dairy products in endemic areas or in people who consume illegally imported unpasteurized Mexican dairy products. Those at high risk include herders, farmers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers. Hunters who handle carcasses of large game such as deer, elk, and wild pigs are also at risk.

![]() People can become infected by ingestion or inhalation of the pathogens or via contact through conjunctiva or open skin. The bacteria then invade reticuloendothelial tissues and typically evade host defenses as intracellular pathogens.51

People can become infected by ingestion or inhalation of the pathogens or via contact through conjunctiva or open skin. The bacteria then invade reticuloendothelial tissues and typically evade host defenses as intracellular pathogens.51

![]() Contaminated unpasteurized milk or cheese is the most common source for human infection. Also, direct contact with infected animals, their placentae, or excreta may allow organisms to enter through abraded skin. Droplet inhalation can occur in abattoir workers. Brucella multiply intracellularly in many tissues and may persist for prolonged periods, leading to acute and chronic disease. Although Brucella is an intracellular pathogen, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients do not have more frequent or severe disease.

Contaminated unpasteurized milk or cheese is the most common source for human infection. Also, direct contact with infected animals, their placentae, or excreta may allow organisms to enter through abraded skin. Droplet inhalation can occur in abattoir workers. Brucella multiply intracellularly in many tissues and may persist for prolonged periods, leading to acute and chronic disease. Although Brucella is an intracellular pathogen, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients do not have more frequent or severe disease.

![]() In the past, most US infections were due to B. abortus after contact with infected cattle and dairy products. This species may cause bovine abortions and stillbirths, so handling infected fetuses or placentae is risky. Dog owners are at increased risk of infections with B. canis.49

In the past, most US infections were due to B. abortus after contact with infected cattle and dairy products. This species may cause bovine abortions and stillbirths, so handling infected fetuses or placentae is risky. Dog owners are at increased risk of infections with B. canis.49

![]() The incubation period varies and is usually 1–3 weeks, but may be 2 months or longer. The disease presents either as an acute febrile, flu-like bacteremic syndrome or as a chronic disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms such as weakness, anorexia, headache, and low-grade fever. Relapses occur in approximately 15% of patients, often after an ineffective antibiotic regimen.

The incubation period varies and is usually 1–3 weeks, but may be 2 months or longer. The disease presents either as an acute febrile, flu-like bacteremic syndrome or as a chronic disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms such as weakness, anorexia, headache, and low-grade fever. Relapses occur in approximately 15% of patients, often after an ineffective antibiotic regimen.

![]() Skin manifestations occur in fewer than 5% of patients and are more common in children than in adults. Furthermore, skin lesions, when present, vary widely, appearing as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, panniculitis, abscesses, and polymorphous papules, pustules, and papulosquamous lesions. This is because cutaneous brucellosis can be related to direct inoculation, hematogenous spread, deposition of antigen–antibody complexes, or hypersensitivity reactions. Children with acute cutaneous brucellosis typically have a violaceous papulonodular eruption primarily on the trunk and lower extremities. Rarely, Brucella-related osteomyelitis or suppurative lymph nodes may create cutaneous abscesses or sinuses.52–57

Skin manifestations occur in fewer than 5% of patients and are more common in children than in adults. Furthermore, skin lesions, when present, vary widely, appearing as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, panniculitis, abscesses, and polymorphous papules, pustules, and papulosquamous lesions. This is because cutaneous brucellosis can be related to direct inoculation, hematogenous spread, deposition of antigen–antibody complexes, or hypersensitivity reactions. Children with acute cutaneous brucellosis typically have a violaceous papulonodular eruption primarily on the trunk and lower extremities. Rarely, Brucella-related osteomyelitis or suppurative lymph nodes may create cutaneous abscesses or sinuses.52–57

![]() A rare but distinctive dermatosis is seen in veterinarians or farmers who handle infected animals or tissues58 and develop a severe contact hypersensitivity reaction to brucella antigens. This presents with discrete, elevated, red papules on the hands or arms that may ulcerate. Needle-stick injuries while handling the live attenuated Brucella vaccine also causes local reactions.44

A rare but distinctive dermatosis is seen in veterinarians or farmers who handle infected animals or tissues58 and develop a severe contact hypersensitivity reaction to brucella antigens. This presents with discrete, elevated, red papules on the hands or arms that may ulcerate. Needle-stick injuries while handling the live attenuated Brucella vaccine also causes local reactions.44

![]() Brucellosis can involve every organ system, although there are no pathognomic clinical findings. The disease can be debilitating but it is rarely fatal. Joints, reproductive organs, liver, and the central nervous system are, in order, the most frequently involved. Nearly all patients have a characteristic undulant fever (alternating pattern of several febrile days followed by several afebrile days). Arthritis can be axial (e.g., sacroiliitis) or peripheral. The disease shows a predilection for reproductive organs, which leads to miscarriages, stillbirths, mastitis, prostatitis, orchitis, and epididymitis. Spinal osteomyelitis is well described, and endocarditis can be fatal. Persistent neuropsychiatric findings occur in 5% of patients.51

Brucellosis can involve every organ system, although there are no pathognomic clinical findings. The disease can be debilitating but it is rarely fatal. Joints, reproductive organs, liver, and the central nervous system are, in order, the most frequently involved. Nearly all patients have a characteristic undulant fever (alternating pattern of several febrile days followed by several afebrile days). Arthritis can be axial (e.g., sacroiliitis) or peripheral. The disease shows a predilection for reproductive organs, which leads to miscarriages, stillbirths, mastitis, prostatitis, orchitis, and epididymitis. Spinal osteomyelitis is well described, and endocarditis can be fatal. Persistent neuropsychiatric findings occur in 5% of patients.51

![]() Patients often have leukopenia, anemia, and elevated liver enzymes. Blood cultures may be positive during the acute illness. Because organisms are easily aerosolized and highly infectious, culture must be under Biosafety Level III conditions. Brucella are nonmotile, coccobacillary Gram-negative rods that grow best in enriched media and hypercapnic conditions with 8%–10% CO2. Serodiagnosis is challenging.51

Patients often have leukopenia, anemia, and elevated liver enzymes. Blood cultures may be positive during the acute illness. Because organisms are easily aerosolized and highly infectious, culture must be under Biosafety Level III conditions. Brucella are nonmotile, coccobacillary Gram-negative rods that grow best in enriched media and hypercapnic conditions with 8%–10% CO2. Serodiagnosis is challenging.51

![]() The papulonodular eruption shows focal perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous inflammation. Macular lesions have a nonspecific mild lymph perivascular infiltrate. The panniculitis usually shows septolobular inflammation with abundant plasma cells. Hepatic and splenic lesions contain small, noncaseating granulomas. Caseation necrosis and calcification may occur in B. suis infections.48,49

The papulonodular eruption shows focal perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous inflammation. Macular lesions have a nonspecific mild lymph perivascular infiltrate. The panniculitis usually shows septolobular inflammation with abundant plasma cells. Hepatic and splenic lesions contain small, noncaseating granulomas. Caseation necrosis and calcification may occur in B. suis infections.48,49

![]() The clinical diagnosis of brucellosis is challenging and the epidemiologic suspicion is often delayed. Confirmation by culture or by serological techniques is necessary but the laboratory techniques are difficult.51 The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of epidemiologic information, coupled with isolation of the organism, finding high or rising agglutination titers, or detecting organisms from a clinical specimen by direct fluorescent antibody technique. For cultures, bone marrow specimens have the highest yield. An agglutination titer of greater than 1:160 is sufficient to begin treatment. Confirmatory titers should be obtained 7–14 days later. In chronic disease, IgG antibodies indicate continuing or recrudescent infection. Cross-reactions with Francisella tularensis, the cause of tularemia, are known, and recent cholera vaccination may stimulate a false-positive Brucella agglutination.

The clinical diagnosis of brucellosis is challenging and the epidemiologic suspicion is often delayed. Confirmation by culture or by serological techniques is necessary but the laboratory techniques are difficult.51 The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of epidemiologic information, coupled with isolation of the organism, finding high or rising agglutination titers, or detecting organisms from a clinical specimen by direct fluorescent antibody technique. For cultures, bone marrow specimens have the highest yield. An agglutination titer of greater than 1:160 is sufficient to begin treatment. Confirmatory titers should be obtained 7–14 days later. In chronic disease, IgG antibodies indicate continuing or recrudescent infection. Cross-reactions with Francisella tularensis, the cause of tularemia, are known, and recent cholera vaccination may stimulate a false-positive Brucella agglutination.

![]() The differential diagnosis includes other acute bacterial infections such as salmonellosis, listeriosis, tuberculosis, and endocarditis. Hodgkin disease may mimic many findings of brucellosis. Vertebral osteomyelitis is sometimes the sole manifestation of brucellosis.

The differential diagnosis includes other acute bacterial infections such as salmonellosis, listeriosis, tuberculosis, and endocarditis. Hodgkin disease may mimic many findings of brucellosis. Vertebral osteomyelitis is sometimes the sole manifestation of brucellosis.

![]() Brucellosis requires prolonged multidrug therapy with antimicrobials that penetrate into cells. Optimal therapy consists of doxycycline combined with either streptomycin, which is difficult to obtain, or gentamicin. The World Health Organization recommends an oral–oral regimen of doxycycline and rifampin (see Table 183-1). Treatment should last at least 6 weeks; shorter courses carry a risk for relapse.51

Brucellosis requires prolonged multidrug therapy with antimicrobials that penetrate into cells. Optimal therapy consists of doxycycline combined with either streptomycin, which is difficult to obtain, or gentamicin. The World Health Organization recommends an oral–oral regimen of doxycycline and rifampin (see Table 183-1). Treatment should last at least 6 weeks; shorter courses carry a risk for relapse.51

![]() Perhaps 5% of brucellosis patients die, mostly because of B. melitensis endocarditis. Early treatment results in rapid improvement but relapses occur in about 10%–15% of patients with suboptimal treatment. Chronic brucellosis can cause disabling fevers, arthritis, fatigue, and nonspecific neuropsychiatric changes.50

Perhaps 5% of brucellosis patients die, mostly because of B. melitensis endocarditis. Early treatment results in rapid improvement but relapses occur in about 10%–15% of patients with suboptimal treatment. Chronic brucellosis can cause disabling fevers, arthritis, fatigue, and nonspecific neuropsychiatric changes.50

![]() In Western nations, brucellosis is largely preventable through occupational precautions such as wearing gloves when handling game or products of conception from livestock. People should avoid unpasteurized dairy products and be especially vigilant when traveling in endemic countries. Vaccines exist for animals but not humans. Brucellosis is a reportable disease and any occurrence should initiate a search for—and possible destruction of—the animal or food source. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) categorizes Brucella as a Category B bioweapon so a criminal source must be considered as well.49,51

In Western nations, brucellosis is largely preventable through occupational precautions such as wearing gloves when handling game or products of conception from livestock. People should avoid unpasteurized dairy products and be especially vigilant when traveling in endemic countries. Vaccines exist for animals but not humans. Brucellosis is a reportable disease and any occurrence should initiate a search for—and possible destruction of—the animal or food source. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) categorizes Brucella as a Category B bioweapon so a criminal source must be considered as well.49,51

Glanders

|

![]() Glanders is a rare zoonosis caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Burkholderia mallei (formerly Pseudomonas mallei). Glanders occurs mostly in horses, mules, donkeys, and related species, and exists focally in Asia and the Middle East. The disease is usually fatal in donkeys and mules but may cause a chronic suppurative condition, called farcy, in horses. Human cases are usually the result of direct exposures to animal reservoirs. In endemic areas, animal handlers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers have the greatest risks of exposure.59–61

Glanders is a rare zoonosis caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Burkholderia mallei (formerly Pseudomonas mallei). Glanders occurs mostly in horses, mules, donkeys, and related species, and exists focally in Asia and the Middle East. The disease is usually fatal in donkeys and mules but may cause a chronic suppurative condition, called farcy, in horses. Human cases are usually the result of direct exposures to animal reservoirs. In endemic areas, animal handlers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers have the greatest risks of exposure.59–61

![]() Human glanders may present in several ways, depending whether the disease is transmitted via cutaneous inoculation or respiratory inhalation:62,63: acute localized infection, chronic cutaneous infection, acute pulmonary disease, and septicemia. Most cases are acquired transcutaneously, and a local ulcer develops within 1–5 days. Regional lymph nodes may then enlarge, producing a ulceroglandular syndrome.

Human glanders may present in several ways, depending whether the disease is transmitted via cutaneous inoculation or respiratory inhalation:62,63: acute localized infection, chronic cutaneous infection, acute pulmonary disease, and septicemia. Most cases are acquired transcutaneously, and a local ulcer develops within 1–5 days. Regional lymph nodes may then enlarge, producing a ulceroglandular syndrome.

![]() Two types of cutaneous glanders are: (1) an acute, febrile, disseminated, infectious process that may resolve in a few weeks or (2) an indolent, relapsing, chronic infection, with multiple cutaneous or subcutaneous abscesses and draining sinuses. Abscesses may develop in muscle, liver, or spleen.

Two types of cutaneous glanders are: (1) an acute, febrile, disseminated, infectious process that may resolve in a few weeks or (2) an indolent, relapsing, chronic infection, with multiple cutaneous or subcutaneous abscesses and draining sinuses. Abscesses may develop in muscle, liver, or spleen.

![]() In acute glanders, a nodule surrounded by cellulitis appears at the site of inoculation (see Table 183-1). Local swelling and suppuration occur, the lesion ulcerates, and regional lymphadenopathy develops. The ulcer is painful and has irregular edges with a gray–yellow base. Nodules rapidly develop along lymphatics that drain the initial lesion. These become necrotic and ulcerated, forming sinuses. Widespread dissemination quickly follows, with multiple nodular necrotic abscesses in subcutaneous tissues and muscle. Lesions frequently coalesce into gangrenous areas.

In acute glanders, a nodule surrounded by cellulitis appears at the site of inoculation (see Table 183-1). Local swelling and suppuration occur, the lesion ulcerates, and regional lymphadenopathy develops. The ulcer is painful and has irregular edges with a gray–yellow base. Nodules rapidly develop along lymphatics that drain the initial lesion. These become necrotic and ulcerated, forming sinuses. Widespread dissemination quickly follows, with multiple nodular necrotic abscesses in subcutaneous tissues and muscle. Lesions frequently coalesce into gangrenous areas.

![]() During bacteremic spread, patients have fevers, rigors, and night sweats. The characteristic eruption is composed of crops of papules, bullae, and pustules. These may be generalized or localized to the face and neck, in which case involvement of the nasal mucosa, either initially or by secondary spread, is prominent. Mucopurulent, bloody nasal discharge is common. Infection may spread to the paranasal sinuses, pharynx, and lungs.

During bacteremic spread, patients have fevers, rigors, and night sweats. The characteristic eruption is composed of crops of papules, bullae, and pustules. These may be generalized or localized to the face and neck, in which case involvement of the nasal mucosa, either initially or by secondary spread, is prominent. Mucopurulent, bloody nasal discharge is common. Infection may spread to the paranasal sinuses, pharynx, and lungs.

![]() In chronic glanders, cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules appear on the extremities and occasionally on the face. The lesions ulcerate, and draining sinuses develop. Ulceration of the hard palate and perforation of the nasal septum can occur. If the organisms are inhaled, pulmonary disease may produce pneumonia, pulmonary abscesses, or pleural effusions. Septicemic glanders is usually fatal.

In chronic glanders, cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules appear on the extremities and occasionally on the face. The lesions ulcerate, and draining sinuses develop. Ulceration of the hard palate and perforation of the nasal septum can occur. If the organisms are inhaled, pulmonary disease may produce pneumonia, pulmonary abscesses, or pleural effusions. Septicemic glanders is usually fatal.

![]() Histopathologic examination of the skin and other involved organs shows a suppurative, necrotic process containing numerous intracellular and extracellular bacteria. Chronic glanders causes granulomatous changes.

Histopathologic examination of the skin and other involved organs shows a suppurative, necrotic process containing numerous intracellular and extracellular bacteria. Chronic glanders causes granulomatous changes.

![]() The diagnosis is made on an epidemiologic basis, examination of Gram-stained smears of pus, and isolation of the organism from abscesses. Furthermore, in the pulmonary and septicemic forms, organisms may be recovered from blood, sputum, or urine. Acute glanders may resemble miliary tuberculosis. The multiple subcutaneous abscesses suggest staphylococcal or deep fungal infections or melioidosis. Lymphonodular disease resembles sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, tularemia, New World leishmaniasis, and Mycobacterium marinum infection.

The diagnosis is made on an epidemiologic basis, examination of Gram-stained smears of pus, and isolation of the organism from abscesses. Furthermore, in the pulmonary and septicemic forms, organisms may be recovered from blood, sputum, or urine. Acute glanders may resemble miliary tuberculosis. The multiple subcutaneous abscesses suggest staphylococcal or deep fungal infections or melioidosis. Lymphonodular disease resembles sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, tularemia, New World leishmaniasis, and Mycobacterium marinum infection.

![]() The CDC recommends treatment with sulfadiazine, although in vitro data indicate that B. mallei is susceptible to ceftazidime, gentamicin, doxycycline, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin. Patients with subcutaneous or visceral abscesses may require treatment for up to 1 year.62–64 Because the disease has largely disappeared, few evidence-based recommendations are available.

The CDC recommends treatment with sulfadiazine, although in vitro data indicate that B. mallei is susceptible to ceftazidime, gentamicin, doxycycline, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin. Patients with subcutaneous or visceral abscesses may require treatment for up to 1 year.62–64 Because the disease has largely disappeared, few evidence-based recommendations are available.

![]() Untreated septicemic glanders causes widespread abscesses in lungs, liver, spleen, muscles, and is nearly always fatal.

Untreated septicemic glanders causes widespread abscesses in lungs, liver, spleen, muscles, and is nearly always fatal.

![]() The usual way to control zoonotic or epizootic glanders has been to destroy infected animals. Such measures have nearly eradicated this once common equine infection and eliminated transmission to humans in industrialized countries. In the United States, glanders is a reportable disease. There are no vaccines against B. mallei infection for humans or animals. However, vaccines might be developed because of the bioweapon potential of this pathogen.61

The usual way to control zoonotic or epizootic glanders has been to destroy infected animals. Such measures have nearly eradicated this once common equine infection and eliminated transmission to humans in industrialized countries. In the United States, glanders is a reportable disease. There are no vaccines against B. mallei infection for humans or animals. However, vaccines might be developed because of the bioweapon potential of this pathogen.61

Pasteurella Multocida Infections

|

P. multocida is a small, ovoid, Gram-negative rod that can cause local skin infection with regional adenitis after a superficial animal bite, scratch, or lick,65 or septic arthritis and osteomyelitis after a deeper animal bite. Respiratory infections unassociated with trauma occur in rare cases, and bacteremia may accompany meningitis or osteomyelitis.

P. multocida commonly colonizes the oropharynx and nasopharynx of healthy cats, dogs, rats, mice, pigs and other livestock, and poultry. Nearly all patients with P. multocida infection have had animal exposure, most commonly a dog or cat bite. Cat teeth are often longer and sharper than those of dogs and therefore may penetrate more deeply to cause septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Compromising conditions such as cirrhosis, malignancy, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease coexist in most severe cases.66–71

Neonatal pasteurellosis can be acquired by exposure to animals, usually pet dogs and cats in the household, even without known or recognized traumatic contact, possibly via respiratory droplets from the animal, or via vertical transmission from an asymptomatic mother.72

Local pain and swelling occur within a few days of an animal bite or contact exposure. Fever is uncommon.

Redness, swelling, ulceration, and seropurulent drainage develop at the bite site. Cellulitis may progress rapidly and extensively, producing lymphangitis. Local necrosis may follow, and necrotizing fasciitis with septic shock has been reported.66,73

Regional adenopathy may be present. Deep bites may introduce organisms into a joint or beneath periosteum and cause septic arthritis or osteomyelitis.

Mild leukocytosis is present. After several weeks, a radiograph of underlying bone may show osteomyelitis. The organism is Gram-negative, and Wright–Giemsa stain reveals a bipolar appearance. Histopathologically, an acute pyogenic response is seen.67

The diagnosis is suspected when a painful infection develops rapidly (<2 days) at the site of an animal bite. Approximately 75% of infected cat bites are caused by P. multocida. Local ulceration and proximal lymphadenitis mimic ulceroglandular tularemia, but P. multocida characteristically produces a necrotizing cellulitis and not chancriform syndrome. The diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the organism, although treatment is often initiated according to an animal bite protocol or based on the history of a rapidly appearing painful cellulitis after a dog or cat bite.73,74

Because most animal bite wounds show polymicrobial contamination, an amoxicillin/clavulanic acid preparation should be started after a dog or cat bite. Although P. multocida is a Gram-negative organism, most strains are susceptible to penicillin, which is the drug of choice if only Pasteurella is cultured. If one suspects that the bite reached periosteum, parenteral penicillin should be given until the local lesion is well healed. P. multocida is also susceptible to doxycycline, later-generation cephalosporins, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (see Table 183-1).

Infection usually responds promptly to antibiotic therapy. Osteomyelitis, abscesses, and remnant foreign bodies should be treated surgically as well as medically. P. multocida infections may be more severe or lead to sepsis in immunocompromised or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.

A great many animal bites are unprovoked by family pets onto a child’s hand, therefore judicious selection of pets and instruction to children are useful, but not guaranteed, ways to reduce domestic animal bites.75

Rat-Bite Fever

|

![]() The term rat-bite fever applies to two clinically similar zoonoses that are both attributable to contact with rats or their excreta. The more common form is caused by Streptobacillus moniliformis, a pleomorphic Gram-negative rod found in the nasopharyngeal flora of most wild and laboratory rats, which are asymptomatic carriers, and is excreted in their urine.76 Carnivores that prey on wild rodents may also transmit infection. Infections with S. moniliformis arise in two ways: (1) direct contact with infected animals, usually through a bite, or (2) ingestion of food or drink contaminated by rat urine, feces, or other secretions.77 In both forms, patients have an acute flu-like infection characterized by a clinical triad of fever, polyarthralgias or arthritis, and rash. In 1926, an outbreak in Haverhill, Massachusetts, caused by consumption of milk tainted by rat excreta led to the designation Haverhill fever or erythema arthriticum epidemicum.

The term rat-bite fever applies to two clinically similar zoonoses that are both attributable to contact with rats or their excreta. The more common form is caused by Streptobacillus moniliformis, a pleomorphic Gram-negative rod found in the nasopharyngeal flora of most wild and laboratory rats, which are asymptomatic carriers, and is excreted in their urine.76 Carnivores that prey on wild rodents may also transmit infection. Infections with S. moniliformis arise in two ways: (1) direct contact with infected animals, usually through a bite, or (2) ingestion of food or drink contaminated by rat urine, feces, or other secretions.77 In both forms, patients have an acute flu-like infection characterized by a clinical triad of fever, polyarthralgias or arthritis, and rash. In 1926, an outbreak in Haverhill, Massachusetts, caused by consumption of milk tainted by rat excreta led to the designation Haverhill fever or erythema arthriticum epidemicum.

![]() The other pathogen implicated in rat-bite fever is Spirillum minus, a Gram-negative spirochete. Spirillary rat-bite fever differs in its geographic distribution, incubation period, and milder arthritis. It occurs almost exclusively in East Asia. Its Japanese name is sodoku.75

The other pathogen implicated in rat-bite fever is Spirillum minus, a Gram-negative spirochete. Spirillary rat-bite fever differs in its geographic distribution, incubation period, and milder arthritis. It occurs almost exclusively in East Asia. Its Japanese name is sodoku.75

![]() Both diseases are most common where people live in crowded, unsanitary conditions ideal for rats. Although streptobacillary fever occurs worldwide, it is most common in Asia. Most US cases occur in children with a new pet rat. Person-to-person transmission is unknown. Rat-bite fever is nonreportable so its exact incidence is not known.78

Both diseases are most common where people live in crowded, unsanitary conditions ideal for rats. Although streptobacillary fever occurs worldwide, it is most common in Asia. Most US cases occur in children with a new pet rat. Person-to-person transmission is unknown. Rat-bite fever is nonreportable so its exact incidence is not known.78