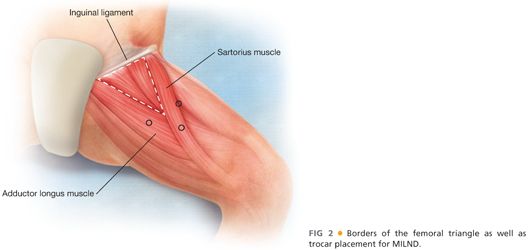

■ The borders of the femoral triangle are graphically depicted in FIG 2.

NATURAL HISTORY

■ Complete inguinal lymph node dissection is advised for any patient with melanoma metastatic to the inguinal lymph nodes in the absence of distant metastases. Microscopic and macroscopic subclassifications of stage III disease are distinguished as clinical and not pathologic entities.1 If disease is detected by physical exam, this is considered macroscopic, whereas a positive sentinel lymph node (SLN) represents microscopic disease regardless of the tumor burden identified pathologically. Stage III melanoma patients represent a very heterogeneous cohort and prognosis varies greatly based on the number of positive lymph nodes, nodal burden in the lymph nodes, and presence or absence of synchronous in-transit metastasis. Five-year overall survival for this group of patients is approximately 50%, but based on the specific subcategory varies widely from 25% to 75%.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ An MILND is indicated in most cases that would be considered for traditional inguinal nodal dissection including melanoma; cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); and some urologic (penile), gynecologic (vulvar), anal, or low-lying rectal cancers.

■ Physical examination should not only evaluate the inguinal nodal basin but also identify in-transit disease between the primary and inguinal nodal basin, particularly in the case of melanoma. Radiographic or gross nodal disease can be found cephalad to the inguinal ligament and superficial to the external oblique aponeurosis, especially in cases of a truncal primary.

■ For lower extremity disease, the popliteal nodal basin should be evaluated; and for disease of the trunk, consideration for contralateral inguinal or axillary drainage needs to be considered based on location of the primary.

■ Physical examination should also evaluate for prior scars in the field (sentinel lymph node biopsy [SLNB] or saphenous vein harvest from prior coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]) and skin changes suggestive of cutaneous involvement. This can be direct extension with overlying cutaneous hyperemia and fixation of disease or nodularity/ulceration that is often seen in SCC. For penile primaries, the genitals and base of penis should be inspected for cutaneous involvement.

■ Most frequently, an MILND will be performed for microscopic disease following a positive SLNB. In this setting, waiting a minimum of 6 weeks from the SLNB to the MILND allows time for the acute operative inflammatory changes to resolve. An MILND may be considered in selected cases of macroscopic disease. Caution and sound clinical judgment should be used to avoid violating the specimen, assuring an en bloc resection and for radiographic disease, that the identified disease to be resected will indeed be contained inside the contents of dissection.

■ MILND is contraindicated in the setting of cutaneous involvement or a prior lymphadenectomy in the same field. MILND may be considered in a prior radiated field, but again, caution should be stressed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Positive SLNB for microscopic disease

■ In general, this is a delayed diagnosis and MILND is offered as a staged procedure, as typically, frozen section is not performed on SLNs for melanoma. Even in institutions where frozen section is performed on SLNs (such as our own), there is no need to freeze the SLNs of the groin if MILND may be offered at a later date.

■ The yield of systemic imaging to find clinically occult stage IV disease after a positive SLN is less than 5% and typically not warranted prior to MILND.2–4

■ Deep pelvic (external iliac/obturator) node dissection is typically not required.

■ Clinical inguinal regional nodal disease

■ In the setting of a palpable inguinal lymph node, a fine needle aspiration (FNA) to confirm the clinical diagnosis is frequently appropriate prior to embarking on an inguinal node dissection.

■ A search for systemic disease with whole-body imaging (computed tomography [CT] scan or positron emission tomography [PET]/CT) is reasonable prior to MILND as the true positive rate is above 10%.5,6

■ The decision to embrace a routine, selective or nihilistic, and hence, almost never approach to the pelvic basin will not be covered in this section. In general, for clinically apparent disease, I strongly consider a combined deep pelvic node dissection at the same setting.

■ There is limited data on minimally invasive approach to the pelvic lymph nodes for melanoma. Technically, it can be performed as clearly shown in clinical practice with gynecologic and urologic procedures. However, the role in melanoma is not defined. Basic questions such as, “Should an extraperitoneal versus an intraperitoneal approach be used?” and “Is converting an extraperitoneal disease to an intraperitoneal operation sound?” have not been established. At the time of this writing, when performing a combined inguinal and a pelvic node dissection, I personally perform this as an open approach.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ The current standard, off protocol, is for a regional node dissection for all cases of a positive SLN, including immunohistochemical disease only.

■ At the time of this publication, the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (MSLT II) randomizing patients with a positive SLNB to observation of the basin or standard lymph node dissection, just closed to accrual.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ A word of caution: Data on short- and long-term morbidity are limited at the time of this publication.7,8 Seromas are common and can be prolonged; wound complications requiring more than outpatient oral antibiotics are rare. Randomized single institution (Delman, personal communication, February 2013) and single-arm multi-institutional surgical trials (NCT01500304) are actively ongoing to define the short-term morbidity and surgical learning curve for this procedure. One measure of oncologic adequacy of the procedure is lymph node yield and this appears to be similar.7,9 There is no data to date regarding oncologic outcomes and patients need to be clearly made aware, that as of the time of this publication, it is unknown if the regional control and cure rates with this approach are worse, better, or equivalent to a standard open approach. This candid discussion is necessary as part of the informed consent process (at the time of this printing one manuscript has been published).9

Preoperative Planning

■ Preoperative baseline bilateral limb volumes should be considered.

■ Brief with anesthesia and the operating room (OR) team prior to the start of the procedure:

■ Hypercarbia is to be expected. Unlike laparoscopy performed in an intraperitoneal location, this entire dissection is performed in the subcutaneous plane and much higher levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) will be systemically absorbed. Anesthesia team needs to be aware and appropriate ventilatory modifications made to avoid the need for conversion.

■ Ensure you have towers in correct position, patient position is rehearsed, and desired equipment, including dissector and laparoscopic supplies, are in the room.

■ Prophylactic antibiotics are provided.

■ Mechanical venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in the form of sequential compression devices are placed on the contralateral leg. Chemical VTE prophylaxis in the form of subcutaneous heparin is provided prior to incision and ideally prior to induction of general anesthesia.

■ A Foley catheter is placed sterilely on the prepped field and sealed out of the dissection field with the genitalia by a sterile towel and Ioban.

Positioning

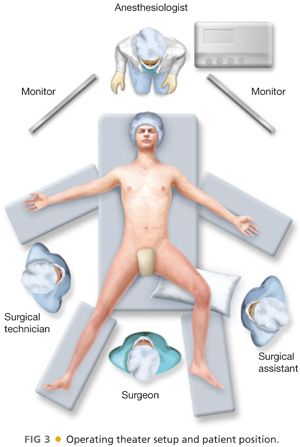

■ In the typical setup, the patient is positioned supine with the legs split either on a split-leg table (my preference) or in the synchronous position with Yellofin gel stirrups. The operative leg is abducted and slightly flexed at the knee (FIG 3). If the leg is left straight, the surgeon will almost inevitably perform the dissection too lateral. The surgeon and the assistant stand so one is between the legs and the other stands lateral to the operative leg. The surgeon and the assistant may change positions during certain portions of the procedure if desired. The surgical technician stands on the opposite side of the patient’s body.

■ Video towers are placed at the head of the table, one above each shoulder (FIG 3). Minimal operative instrumentation is needed on the Mayo stand. If there is a need to emergently convert, appropriate instruments should be immediately available.

Approach

■ The current approach involves en bloc resection of the muscular fascia and saphenous vein with the lymphadenectomy specimen. The plane of dissection off the sartorius muscle and adductor may not be as apparent with a minimally invasive approach as during an open procedure, and to be clear that the dissection is in the correct plane, we have scored the fascia and visualized the underlying muscle.

■ Resecting the muscular fascia is the approach initially described by Delman et al.10 and the approach we have followed. Whenever embarking on a new procedure, it is critical that caution is exercised and the procedure is approached with this mindset, assuring that the extent of the oncologic resection is at least as complete as the traditional standard for which it is meant to replace. It is also true that the minimally invasive approach should, as much as possible, exactly mirror the technique of the open approach. As with any novel technique, this procedure will likely evolve with time, and with experience, it may be shown that a muscular fascia and saphenous vein preserving approach is as safe and oncologically sound.

■ We do not excise the SLNB scar if present. We also do not make an open incision to confirm the adequacy of dissection because the videoscopic view should make this obvious. If there is any question of inadequate resection, a small proximal incision can be made and the extent of the oncologic operation should not be jeopardized because of a perceived feeling of inadequacy or failure by “converting.”

TECHNIQUES

MINIMALLY INVASIVE INGUINAL LYMPH NODE DISSECTION

Operating Room Setup

■ In the typical setup, the patient is positioned supine with the legs split either on a split-leg table (my strong personal preference) or in the synchronous position with Yellofin gel stirrups. The operative leg is abducted and slightly flexed at the knee (FIG 3). The surgeon and the assistant stand so one is between the legs and the other stands lateral to the operative leg. The surgeon and the assistant may change positions during certain portions of the procedure if desired. The surgical technician stands on the opposite side of the patient’s body.

■ Video towers are placed at the head of the table, one above each shoulder (FIG 3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree