Fig. 2.1

A graph demonstrating the effects of hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia on the epidermis. NO nitric oxide, IGFR insulin-like growth factor receptor, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6 interleukin-6, MMP matrix metalloproteinase, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

The mechanisms by which hyperglycemia causes these sequelae are complex. Elevated glucose levels have been found to decrease diabetics’ cutaneous fibroblasts’ synthetic, proliferative, and secreting abilities, thereby hindering wound healing. The fibroblasts become resistant to growth factor such as IGFR-I and epidermal growth factor (EGF), further inhibiting proliferation. Ultimately this resistance causes sensitization to ischemia, resulting in the significant ulceration and necrosis of lower extremities common in diabetics [4, 5].

Hyperglycemia further affects fibroblasts by releasing inflammatory cytokines and free radicals, causing oxidative stress, cell death and aging. Glucose produces these free radicals by altering the electron transport chain during oxidative respiration, causing auto-oxidation. Once produced, free radicals and advanced glycoxidation end products (AGEs) affect mitochondria and endothelial synthesis, resulting in protein misfolding, impaired vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production, the release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, MMP-3, and MMP-2, causing apoptosis [4].

Hyperglycemia also affects endothelial cells, resulting in vascular damage. Similar to fibroblasts, endothelial cells are made dysfunctional by insulin resistance and free radicals. Hyperglycemia increases endothelial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage and cell death and prevents the endothelial cells from releasing nitrous oxide (N0), which under normal physiologic circumstances prevents vascular smooth muscle cell migration. The free radicals produced by hyperglycemia causes significant oxidative stress and inflammation amongst endothelial cells, which further results in vascular permeability and the uncontrolled release of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and interleukin (IL)-6. Again, mitochondria are affected, impacting protein formation as well as mitochondrial DNA [4].

Keratinocytes also are affected by hyperglycemia. In vitro analysis demonstrates that glucose is directly toxic to keratinocytes, reducing proliferation and replication of these cells, hindering re-epithelialization [4]. Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia (which is widespread among type II diabetics) activates keratinocyte insulin growth factor receptors, causing inappropriate epidermal proliferation and dermatologic disease [3, 6].

Diabetics are well known for having an increased risk of cutaneous infections, and while the pathogenesis is poorly understood, the vascular changes caused by hyperglycemia play a significant role. On a macrovascular level, studies suggest that hyperglycemia increases blood viscosity and hypercoagulability (by increasing plasma fibrinogen levels), causing ischemic injury and delivering poor blood supply to affected areas [5]. Infection of this damaged tissue is made worse by microvascular disease as well as associated comorbidities such as peripheral vascular disease and diabetic neuropathy. The immune system itself is hindered by DM as well, as elevated glucose is associated with decreased phagocytosis, impaired leukocyte adherence, and delayed chemotaxis [2, 7].

Clinical Symptoms, Differential Diagnosis, Histology, and Treatment by Cutaneous Manifestation

Common conditions associated with DM include acanthosis nigricans (AN), acrochordons (skin tags), yellow skin and nails, diabetic dermopathy (shin spots), rubeosis faciei, and ulcers on the lower extremity and foot. Uncommon manifestations include diabetic bullae; diabetic thick skin; scleredema diabeticorum, eruptive xanthomas granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica (NL), and perforating dermatosis (see Table 2.1) [3]. Both the common and uncommon conditions will be discussed below.

Table 2.1

Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus

Common | Uncommon |

|---|---|

Acanthosis nigricans | Diabetic bullae |

Acrochordons | Diabetic thick skin |

Carotenoderma | Scleredema diabeticorum |

Diabetic dermopathy | Eruptive xanthomas granuloma annulare |

Rubeosis faciei | Necrobiosis lipoidica |

Diabetic ulcers | Perforating dermatosis |

Infection |

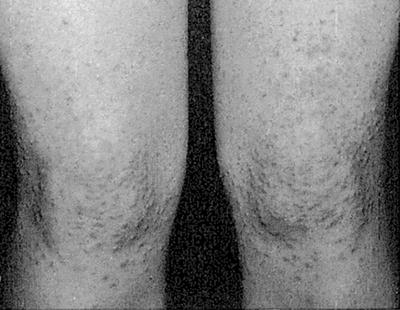

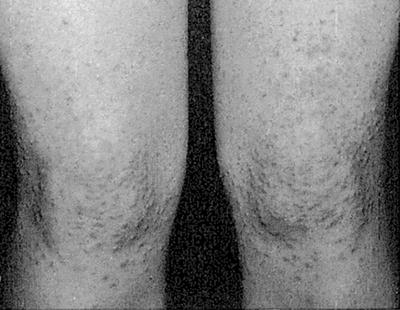

Diabetic Dermopathy (Shin Spots)

Shin spots are the most common cutaneous manifestation of DM, found in approximately 40 % of diabetics [8]. The lesions are well demarcated, hyperpigmented, atrophic, depressions, macules, or papules that are generally located on the anterior surface of the bilateral lower extremities but can also affect the thighs, medial malleoli, and arms [6, 8–10]. Their frequency increases with duration of disease, comorbid findings (specifically microvascular disease such as nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy), and male sex [6, 9]. There is no similar condition in non-diabetics [8]. Although the etiology was thought to be secondary to blunt trauma given their location and association with neuropathy, this finding has not been replicated in vivo. Other studies have looked at the blood flow to these lesions and determined that they have much higher blood flow than normal appearance reference skin sites (although the reference skin of diabetics with diabetic dermopathy has much lower blood flow in general than their matched diabetic and nondiabetic controls) [8, 9]. Histologically, the most common feature observed is hemosiderin and/or melanin pigment in the superficial dermis [9]. General thickening of the blood vessels with a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate has also been identified [3]. The lesions are asymptomatic and oftentimes resolve spontaneously (on average lasting 18–24 months) and so there is no recommended treatment [3].

Acanthosis Nigricans (AN)

AN is described as a velvety thickening and hyperpigmentation of the skin most commonly located on flexural areas, such as the axilla, nape of the neck, and groin area (Fig. 2.2) [3, 11]. It is common amongst diabetics and those with obesity; those with AN have been found to have higher fasting plasma insulin levels than control subjects [3, 11, 12]. AN is less commonly found in hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, genetic disorders, as a paraneoplastic syndrome, or with prolonged crutch use [6, 11]. Histologic samples demonstrate papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and mild acanthosis causing the hyperpigmentation [12, 13]. AN is best treated by management of the underlying disease with weight loss and diabetic control, both of which can reverse the diabetic process. Medications such as octreotide which decrease insulin secretion have also demonstrated some success in treatment, as have agents which decrease the proliferation of keratinocytes, such as topical retinoids [3, 6, 11].

Fig. 2.2

Acanthosis nigricans within the axilla. Source: Ahmed I, Goldstein B. “Diabetes Mellitus.” Clinics in Dermatology. 2006 Jan 1; 24(4):237

Acrochordons (Skin Tags)

Acrochordons are benign pedunculated papules that occur along the neck and other major flexor surfaces such as the eyelid or axilla. They are often associated with AN and have a similar mechanism of development, with hyperinsulinemia stimulating keratinocyte proliferation [6, 10, 13]. Approximately 66–75 % of patients with acrochordons have DM [14]. Differential diagnosis could include warts, nevi, or neurofibromatosis. Histologically, it appears as a polyp with normal epidermis and a core of dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Acrochordons can be treated if desired by surgical removal, cryotherapy, or electrodissection; however, they are benign, and no treatment is necessary [3, 6, 10, 13].

Carotenodermia

Diabetics will often develop yellowing of the skin in areas of prominent sebaceous activity such as the face as well as the palms, soles, and nails; it is notably absent from the sclera. The pathogenesis of this particular condition is unclear but thought to relate to impaired metabolism of beta-carotene by the liver, thus causing its accumulation systemically [3, 15]. Beta carotene is lipophilic, and is thus attracted to the stratum corneum, which has a high lipid content. The high lipophilic state associated with DM further results in elevated beta carotene levels, as beta lipoprotein breaks down to beta carotene [15]. Another mechanism of disease is thought to be caused by glycosylation of dermal collagen, which creates a yellow hue [3, 16]. Differential diagnosis is broad, including jaundice (although in jaundice the sclera are affected), lycopenemia, riboflavinemia, and certain drugs [15]. Generally, treatment includes better glycemic control and decreasing consumption of foods high in carotene [3, 15].

Rubeosis Faciei

Rubeosis faciei is a chronic flushed appearance of the face and neck often found on diabetics (with reports as high as 60 %) [3, 6, 16]. The erythema is thought to directly correlate with dilation of vasculature and microangiopathic changes associated with the disease [3]. The differential includes erysipelas and carcinoid flush, but lacks the warmth and elevation of the former and the telangiectasias of the latter [16]. There is no real treatment except improved glycemic control and symptomatic relief by avoiding vasodilators, such as caffeine and alcohol [6].

Diabetic Foot and Ulceration

Diabetic foot is generally classified as infection, ulceration, and/or destruction of deep tissue secondary to neurologic abnormalities and peripheral vascular disease in the lower limb [17]. It is the most morbid common cutaneous manifestation of diabetes, occurring in approximately 15 % of the diabetic population and accounting for at least 70 % of lower limb amputations annually in the USA [3, 6, 18]. It is the most common cause of hospitalization amongst diabetics [3, 18]. Ulcers occur in areas of constant pressure and repeated movement; initially thick calluses form, and these break down and ulcerate [6]. Ulcer formation is directly related to the loss of protective sensation secondary to peripheral neuropathy or peripheral vascular disease, both common in diabetics [18]. Differential diagnosis includes other causes of ulceration, such as arterial or venous disease. It is imperative to treat these callouses and ulcers with aggressive debridement and offloading with devices such as a total contact cast in order to prevent secondary infection and promote healing [6, 18]. If properly cared for, the ulcers can resolve within weeks as long as vasculature is adequate. If it is inadequate, surgical intervention with revascularization procedures may be necessary, but these procedures have not been studied in large prospective analyses [6, 18].

Necrobiosis Lipoidica (NL)

NL, previously known as necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, is a granulomatous disease that is characterized by red papules or plaques that grow peripherally, with a raised, active, erythematous border, ultimately causing central epidermal atrophy with telangiectasias and a yellow hue (Fig. 2.3) [3, 19]. Although the lesions can be singular, they are often multiple and bilateral, expanding to up to several centimeters in diameters [3]. The lesions develop in both type I and type II diabetics, with earlier onset in insulin dependent diabetics and with a preponderance for females [20]. While the lesions are asymptomatic and chronic, 35 % ulcerate and these can progress to squamous cell carcinoma [3, 10]. Distribution is generally on the anterior shin, but can also occur on the feet, arms, trunk, or scalp—their development is thought to relate to neuropathy, causing the distal nature of disease [3]. Histologically NL lesions are characterized by interstitial palisaded granulomas involving the dermis and subcutis with epidermal atrophy and excess lipid deposits in the dermis [10, 20]. Although 65 % of patients with NL have diabetes, the lesions have also been identified in patients with Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, sarcoid, and granuloma annulare [20]. Because of the chronic and progressive nature of the lesions, treatment is necessary. Unfortunately, it is not very effective. Topical and intralesional steroids have been demonstrated to slow disease progression by decreasing the inflammation, however it can still take years for the lesions to resolve. For persistent disease, systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, ticlopidine, and TNF-α antagonists (such as etanercept and infliximab) have been used. Skin grafting remains another treatment option, although the poor wound healing and increased chance of infections associated with DM makes surgery less desirable [6, 10, 20].

Fig. 2.3

An example of nicrobiosis lipoidica. Source: Ahmed I, Goldstein B. “Diabetes Mellitus.” Clinics in Dermatology. 2006 Jan 1; 24(4):237

Bullosis Diabeticorum (Diabetic Blisters)

Blisters have been found to occur spontaneously on the hands and feet without surrounding or predisposing erythema or inflammation in approximately 0.5 % of diabetic patients (Fig. 2.4) [10, 21]. The blisters are tense and painless, containing sterile fluid and ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 cm in size [6]. Generally the bullae form abruptly and heal without scarring, as histologically they are predominately intra-epidermal; however, occasionally hemorrhagic bullae can form or the lesions can have a subepidermal cleavage site that can cause scarring and atrophy [6, 16, 21]. The etiology of the blisters is unclear, as immunophysiologic studies have all been negative [6, 21]. Differential includes other blistering diseases such as bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, bullous impetigo, porphyria, bullous erythema multiforme, and allergic reactions [16, 21]. Treatment of the lesions is generally supportive, as the bullae resolve within 2–4 weeks [6]. Topical antibiotics may be used to prevent infection [6, 16].

Fig. 2.4

Bullosis diabeticorum on the dorsal foot. Source: Kurdi AT. “Bullosis diabeticorum.” The Lancet. 2013 Jan 1; DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60145-2

Scleredema

Scleredema is a rare disorder involving asymptomatic, diffuse, symmetric, nonpitting indurated plaques on the neck, upper back, and shoulders (Fig. 2.5) [6, 22]. It is most common in obese males over the age of 40, and is associated with other complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy. It has an unpredictable course but is generally progressive, worsening with the severity of disease. Histologically the skin demonstrates thickening of the reticular dermis with mucin deposition and proliferation of mast cells between thickened collagen bundles [6, 16]. Scleredema is usually permanent, and treatment is generally ineffective, although therapies including glucocorticoids, methotrexate, and ultraviolet (UV) light therapy have demonstrated some therapeutic success [3, 6, 22]. Tight glycemic control has no effect on the condition [6].

Fig. 2.5

Scleredema of the back. Source: Ahmed I, Goldstein B. “Diabetes Mellitus.” Clinics in Dermatology. 2006 Jan 1; 24(4):237

Diabetic Thick Skin (Scleroderma-Like Skin Changes)

Compared with the general population, diabetics often develop thickened skin, which can be asymptomatic and diffuse or localized with dramatic morbidity. Approximately 20–30 % of diabetic patients develop thickening of the skin on the dorsal hand, which can progress in 8–50 % of diabetics to diabetic hand syndrome, a disease that involves stiffening of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, limiting mobility and occasionally causing Dupuytren contracture or sclerodactyly [3, 10, 23, 24]. When it manifests as diabetic hand syndrome, patients have limitations in extension of their hands, causing the “prayer sign” (an inability to press the palms together) [6]. Huntley papules or finger pebbles are another variant of diabetic thick skin associated with type 2 diabetics. It involves indurated thickened areas of skin localized to the extensor surfaces of the fingers, knuckles, or periungal area [6]. Although similar to scleroderma, scleroderma-like skin changes do not involve dermal atrophy, edema, pain, Raynaud phenomenon, or telangiectasias. Histologically the syndrome lacks evidence of mucin deposition (seen in scleredema diabeticorum); instead, there is a thickened dermis with accumulation of connective tissue in the reticular layer with increased cross-linkage of collagen [24]. Diabetic thick skin is a progressive condition, and is associated with double the risk of retinopathy and nephropathy. Few options are available for treatment; limited evidence exists for tight glycemic control [6].

Acquired Perforating Dermatoses (APD)

APD is a disorder characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and nodules which histologically demonstrate focal hyperkeratosis that is in contact with transepidermal, perforating, elimination of components of the dermis (such as keratin, collagen, and elastic fibers). It can be classified as four subtypes: reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC), perforating folliculitis (PF), Kyrle disease (KD), and (least commonly) elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) [3, 25, 26]. Each of these subtypes has a slightly different morphology and distribution. The lesions generally appear as erythematous papules and nodules, and can sometimes have central umbilication with a keratin plug or follicular pattern of presentation, depending on the subtype. The lesions usually present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and trunk, although EPS and RPC can also appear on the face [3, 26]. The primary symptom associated with the disease is extreme pruritus, which occurs over 70 % of the time [25]. The lesions are more common in diabetics with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who are undergoing hemodialysis (HD), with a frequency of 5–10 % in this population [6]. APD is worsened by the Köbner effect [25]. The lesions can resolve on their own if scratching and further trauma are avoided, although steroids (topical or systemic), retinoids, allopurinol, and phototherapy have all been used for healing and symptomatic control of their pruritus [6].

Eruptive Xanthomas

Eruptive xanthomas are a collection of yellow, rapidly developing papules with an erythematous halo commonly located on the extensor surface of the extremities (Fig. 2.6) [3, 10]. Histologically they appear as well circumscribed infiltrate of foam cells, histiocytes, and fat cells within the dermis [10, 27]. They are composed entirely of triglycerides, not cholesterol esters, thus differing from most other types of xanthomas [6]. The lesions have been clearly demonstrated to be associated with hypertriglyceridemia as well as hyperglycemia, and can show rapid and complete improvement with systemic glycemic control [3, 6].

Fig. 2.6

Hundreds of small papules consistent with eruptive xanthoma. Source: Perez M, Kohn S. “Cutaneous Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1994 Apr 1; 30(4):519

Cutaneous Infections

Dermatologic infections occur in 20–50 % of diabetic patients, particularly in type II diabetics and those with poor glycemic control [10, 14]. Candidal and dermatophyte infections can oftentimes be the first sign of undiagnosed diabetes [10]. Additionally, bacterial infections in diabetics such as impetigo, folliculitis, carbuncles, furuncles, ecthyma, erythrasma, and erysipelas are more common and more severe in diabetic patients, as are more severe bacterial or fungal infections such as necrotizing fasciitis, malignant otitis externa, and rhinocerebral mucormycosis [10, 14]. It is imperative to diagnose and treat these infections early to prevent life-threatening consequences.

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is the syndrome of diseases caused by extracellular deposition of amyloid, a group of proteins that form characteristic fibrillary aggregates which, when deposited, interfere with normal tissue structure and function [28–30]. The clinical significance of the deposition varies considerably, ranging from asymptomatic to multiorgan failure (including CKD) [29, 30]. The nature and progression of disease partly relates to the type of protein, or amyloid, deposited—there are approximately 25 proteins currently known to cause amyloidosis, all of which are pathogenic variations of normal precursor proteins [28, 29]. Etiology is thought to be secondary to malignancy, chronic inflammation, or mutation with can occur either idiopathically, hereditarily, with advanced age, or with myeloma [28, 29, 31].

Cutaneous manifestations of the disease can be divided into two categories: primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA) and systemic amyloidosis with cutaneous involvement [28] (Table 2.2). Both subtypes involve the deposition of amyloid into the extracellular space of the dermis; however, cutaneous amyloidosis is limited while systemic amyloidosis affects organ systems outside of the skin, resulting in an obvious discrepancy between the severity and prognostic indices of both diagnoses [28].

Table 2.2

Differences between primary localized cutaneous and systemic amyloidosis

Primary localized cutaneous amyloid | Systemic amyloid with cutaneous manifestations | |

|---|---|---|

Amyloid present | AK; AL with nodular amyloid | Non-AK amyloid, can be multiple |

Appearance | Macular amyloidosis: Poorly delineated brownish patches or linear rippling of the skin with grayish-brown macules Lichen amyloidosis: Pruritic discrete, firm, hyperkeratotic, dome-shaped, skin colored to brownish papules | Pruritic waxy translucent papulonodular masses |

Deposit location | Superficial; dermal papillae and subpapillary layers | Deep; dermal papillae, subpapillary layers, stratum reticular, subcutis, dermal appendages, blood vessels |

Epidermal changes | Hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis with thinning of the rete ridges, and expansion of the papillae | None |

Physiology/Pathogenesis

Amyloidosis is a protein folding disorder resulting from the biological failure of our cells to degrade structurally abnormal proteins. These nonfunctional proteins aggregate to form insoluble amyloid fibrils [32]. The process by which amyloid fibrils form is poorly understood, but is thought to relate to abnormalities in proteolytic cleavage, the stability of a native protein (kinetic or thermodynamic), production of a conformationally altered protein, or oversecretion of a protein [32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree