Mastopexy and Mastopexy/Augmentation

W. Grant Stevens

Andrea E. Van Pelt

Adrian M. Przybyla

INTRODUCTION/HISTORY

According to ASAPS national statistical data, over 115,000 mastopexies were performed in 2008, a 394% increase from 1997. Mastopexy currently ranks number eight on the list of the most commonly performed aesthetic surgical procedures.1

Although mastopexy techniques have evolved in tandem with innovations in breast reduction, mastopexy involves lifting and shaping by redistributing the tissue without reducing volume. The challenge lies in choosing the right technique to maximize correction of ptosis, minimize scars, and slow the recurrence of ptosis over time.2

Most women seeking mastopexy have a relative deficiency of breast parenchyma within a larger, ptotic skin envelope. Age, gravity, weight fluctuation, pregnancy, and lactation all contribute to the development of breast ptosis and loss of a youthful shape. Loss of elasticity results in stretching and lengthening of skin and glandular attachments. As glandular tissue settles, the upper pole of the breast loses its convexity and appears deflated. Other reasons women seek mastopexy include correction of congenital deformities such as tubular breasts, or to achieve symmetry of the contralateral breast in post-ablative breast reconstruction.3

In the setting of ptosis with considerable glandular atrophy or when the woman desires a larger breast size, mastopexy may be combined with implant augmentation. In some cases, loss of upper pole fullness can be corrected with an implant only. The increased volume from implant augmentation fills the ptotic skin envelope and decreases the amount of skin resection. Other situations such as congenital or acquired breast asymmetries and tuberous deformities may require combined augmentation and mastopexy for optimal aesthetic outcomes.

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION OF PTOSIS

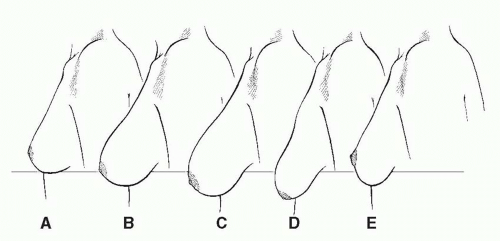

Several classification systems have been devised to better define ptosis. Regnault’s classification is the most widely employed, establishing grades of ptosis based on nipple position in relation to the inframammary fold and the skin envelope. She defines pseudoptosis, partial ptosis, and three degrees of true ptosis4 (Table 54.1 and Figure 54.1).

There have been a number of modifications to Regnault’s classification that take into account components such as skin elasticity, glandular volume, and parenchymal distribution.3 Brink describes a ptotic breast that “pirouettes around its adherent base,” as the nipple rotates inferiorly and descends below the immobilized fold resulting in elongated distances from clavicle to nipple, nipple to inframammary fold, and clavicle to inframammary fold.

PATIENT SELECTION

Women are evaluated in terms of breast volume, the size and quality of the skin envelope, nipple position, areolar size, the degree of ptosis, presence of asymmetry, and their expectations regarding shape and surgical scars.5 The length of the incisions, the amount of skin to be excised, and whether the woman desires modification of breast size are considered. Decreasing the glandular mass with a small reduction can decrease the effects of gravity and recurrence of ptosis. Augmentation may permit shorter incisions by filling the skin envelope but may not satisfactorily address nipple descent.3,6 A flexible surgical plan takes all these variables into account.

Issues related to scar length and breast shape take on added importance in mastopexy compared with reduction. General guidelines based on the degree of ptosis will help determine the best approach. When the nipple has descended 1 to 2 cm below the inframammary fold, surgical elevation of the nipple-areola complex is required for correction. When the nipple is pointing downward and the breast is low, correction requires major reduction of skin and upward position of the nipple-areolar complex. Glandular ptosis can be improved with augmentation or mastopexy, depending on the patient’s desired breast size.3

When evaluating a patient for any type of breast surgery, diligent cancer screening and baseline examinations are performed, including a review of previous mammograms, biopsies, breast scars, breast tissue, and family history of breast cancer. Baseline mammograms are obtained for patients older than 35 years, or earlier in high risk patients. In regard to future breast cancer detection, simple operations with less manipulation and internal repositioning of parenchyma are preferable to limit internal scarring.3

ALGORITHM FOR CHOOSING THE RIGHT PROCEDURE

The senior author (WGS) uses an algorithm based on the degree of required nipple elevation and the woman’s desired postoperative volume.

Pseudoptosis

For women who desire larger breasts, a biplanar augmentation will provide superior fullness to match inferior fullness.

For women who desire the same breast size, a small resection may be performed in conjunction with biplanar augmentation.

Women who desire smaller breasts can undergo an inframammary wedge excision. Grade I ptosis requiring no more than 2 cm nipple elevation

For women who desire larger breasts, an augmentation (preferably biplanar) can be performed with a circumareolar mastopexy.

If the patient desires the same breast volume, a circumareolar mastopexy is performed.

For women who desire smaller breasts, a small reduction may be performed. Grade II ptosis requiring 3 to 4 cm of nipple elevation

For women who desire larger breasts, an augmentation-mastopexy is performed. This may be performed in one or two operative stages depending on the surgeon’s preference and experience. Circumvertical mastopexy is preferred and

may require a horizontal wedge excision depending on the nipple-to-fold distance. Typical distances are 7 to 8 cm for a B cup, 9 to 10 cm for a C cup, and 10 to 11 cm for a D cup breast. Skin and flap undermining are kept to a minimum. The patient should be counseled preoperatively that the resulting shape of the breast takes priority over the presence or absence of a horizontal scar.

TABLE 54.1 REGNAULT’S CLASSIFICATION OF PTOSIS

Minor ptosis (first degree)

Nipple at inframammary fold

Moderate ptosis (second degree)

Nipple below inframammary fold, but above lower breast contour

Severe ptosis (third degree)

Nipple below inframammary fold and at lower breast contour

Glandular ptosis

Nipple above inframammary fold, but breast hangs below fold

Pseudoptosis

Nipple above inframammary fold, but breast is hypoplastic and hangs below fold

FIGURE 54.1. Breast ptosis classification. A. Normal. B. Minor or first degree. C. Moderate or second degree. D. Severe or third degree. E. Glandular ptosis.

For women who want no change in volume, a vertical or Wise pattern mastopexy is performed.

For women who desire smaller breasts, a small glandular reduction is performed. Grade III ptosis requiring >4 cm of nipple elevation

For women who desire larger breasts, a Wise pattern mastopexy-augmentation is performed in one stage. Massive weight loss patients often require a secondary procedure due to poor tissue quality.

For women who desire the same volume, a Wise pattern mastopexy is utilized. For women who desire smaller breasts, a Wise pattern reduction is performed.6

TECHNIQUES

The goal in mastopexy is to restore a firm and youthful breast by reshaping the parenchyma and tightening the ptotic skin envelope, while maintaining nipple-areolar vascularity and minimizing the extent of scarring. Many authors have proposed algorithms to match a certain technique with the degree of ptosis.3,5,6,7 There is no ideal technique and the shortest scar may not necessarily be the best one. Scar reduction at the expense of breast shape, position, or longevity of correction is a poor trade-off; however, some women opt for this.2,8

Skin only mastopexies tend to lose shape over time and accelerate secondary ptosis, particularly in large, heavy breasts. Suturing the gland itself may result in a more durable shape.9,10 Some surgeons advocate suturing the superficial fascial system with permanent sutures.11 Others pass an inferiorly based flap under a pectoralis muscle loop to help maintain suspension.12 In general, smaller corrections require shorter scars, less skin excision, and tissue rearrangement. Skin excisions should allow tightening both vertically and horizontally and encourage reshaping into a more conical shape, while permitting elevation of nipple-areolar complex.3

Although techniques are continuously evolving, three basic scarring patterns remain, each with several variations: circumareolar, circumvertical, and inverted T.

Circumareolar

Circumareolar techniques can be either concentric or eccentric. Removal of a crescent of skin at the upper areolar border provides only minimal elevation of the nipple-areola. This is reserved for 1 cm lifts and eccentric areolae. Concentric periareolar mastopexies can be done with or without remodeling of the gland and are usually limited to small lifts. Circumareolar incisions offer the shortest possible scar pattern with the advantage of scar camouflage at the areolar border. Most surgeons employ circumareolar techniques for correction of grade I ptosis. Features common to all circumareolar techniques include the following: the new areola is circumscribed, points around the areola are connected to form a circle or oval pattern that is larger in diameter than the original areola; skin between the inner and outer diameters is de-epithelialized. Temporary wrinkling and pleating is common postoperatively, which improves over several months. A wider skin excision is associated with a greater degree of skin pleating and flattening of the breast mound, as well as the potential for scar and areolar widening. Flattening can be advantageous in correcting tuberous breast deformity. Spear proposed a series of rules to minimize this tendency for periareolar tension, wrinkling, and complications. As a general guideline, the ratio of outer to inner diameter circumareolar markings should ideally be less than or equal to 2:1, with a maximum ratio of 3:1.13

Because of the criticisms associated with skin-only techniques, several variations of the circumareolar mastopexy were designed to improve breast projection, create upper pole fullness, and prolong the correction of ptosis via parenchymal remodeling. Circumareolar pursestring sutures were added to prevent areolar distortion and scar widening.14,15,16

Benelli developed the round block technique to increase projection and prevent areolar tension. One of two glandular reshaping techniques is used, depending on the degree of support needed. For simple ptosis in small breasts, the base of the breast is plicated and invaginated. He otherwise performs a criss-cross glandular overlap of lateral and medial flaps to increase projection and decrease the base width. Shape is maintained by fixating the glandular cone to pectoralis fascia. Thick skin at the base of the breast is preserved so that it can maintain its supportive function. The round block involves a nonabsorbable pursestring cerclage around the areola. Benelli notes that this technique is not suitable for all mastopexies and that patients must be willing to accept a less than perfect shape in favor of a reduced scar.14,16

Goes developed another circumareolar method of reshaping the breast parenchyma by implanting mesh as an internal

brassiere. After creating skin flaps and reshaping the gland via rotation and plication techniques, a combination absorbable/nonabsorbable mesh is sandwiched between the de-epithelialized periareolar dermis and the redraped skin flap. The periareolar pursestring suture is removed 6 to 9 months postoperatively.15

brassiere. After creating skin flaps and reshaping the gland via rotation and plication techniques, a combination absorbable/nonabsorbable mesh is sandwiched between the de-epithelialized periareolar dermis and the redraped skin flap. The periareolar pursestring suture is removed 6 to 9 months postoperatively.15

Vertical Techniques

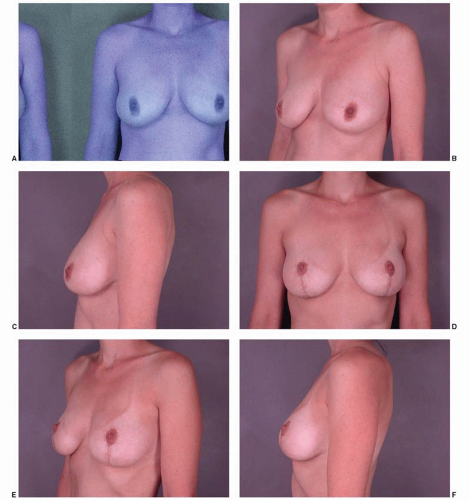

Vertical, or circumvertical, techniques add a vertical or oblique limb to the periareolar scar. They can be used to correct all grades of ptosis, but are predominantly employed in mild to moderate ptosis (Figure 54.2). As an alternative to the traditional inverted T approach, vertical techniques were designed to decrease scarring, improve projection and upper pole fullness, and maintain a long-lasting shape. Skin markings around the areola may be oval or dome shaped or resemble an ice cream cone or parachute. “VOQ” is sometimes used to describe a periareolar “O” atop a vertical “V” that closes to resemble a “Q.”3 In glandular remodeling, the conical shape is often overcorrected, allowing the breast to settle in its final position over several months. Vertical techniques have been criticized for being technically challenging and frequently requiring revision, which has prompted various modifications to make them easier to learn. Lassus, Lejour, Hall-Findlay, and Hammond are the pioneers of vertical scar techniques.

FIGURE 54.2. Circumvertical mastopexy. A–C. Before circumvertical mastopexy. D–F. After circumvertical mastopexy. |

Lassus first published his technique in 1969 and again in 1970.17 Since his original design, Lassus has made modifications to decrease vertical scar length and improve nipple-areolar blood flow. He prefers a superiorly based pedicle for preservation of nipple sensation. In more ptotic breasts requiring greater than 10 cm of nipple-areolar elevation, a lateral or medial pedicle is used. The skin pattern resembles an oval, similar to that of a periareolar mastopexy. A glandular flap is dissected perpendicular to the chest wall medially and laterally, and inferiorly down to the inframammary fold. The inferior portion of the glandular flap is elevated, folded under, and anchored to pectoralis fascia to create fullness and projection. A wedge of skin, with or without gland, is excised from the lower breast. The conical shape is created by centrally coapting the medial and lateral glandular pillars. Lassus describes the postoperative breast shape as “the nose of a Concord,” noting it takes approximately 2 to 2.5 months for the breast to acquire a satisfactory appearance. Immediately post-op the vertical scar may be visible below the inframammary fold, but within 2 to 3 months with descent of the breast, the scar is usually no longer apparent. Lassus would occasionally excise a small horizontal wedge, but later adjusted his technique by elevating the lower marking above the inframammary fold to avoid the horizontal scar.17,18,19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree