7 Mastopexy

Synopsis

Breast ptosis is a common problem caused by several different factors: pregnancy, weight changes, aging, delayed effect of breast implants and developmental deformities.

Breast ptosis is a common problem caused by several different factors: pregnancy, weight changes, aging, delayed effect of breast implants and developmental deformities.

Mastopexy and augmentation-mastopexy techniques are varied and can be applied to different breast shape deformities.

Mastopexy and augmentation-mastopexy techniques are varied and can be applied to different breast shape deformities.

Mastopexy techniques can be periareolar, vertical or based on the inverted-T techniques, as well as being performed in some instances by liposuction alone.

Mastopexy techniques can be periareolar, vertical or based on the inverted-T techniques, as well as being performed in some instances by liposuction alone.

Preoperative deflation prior to mastopexy or augmentation-mastopexy is a safe and effective technique that offers the patient and surgeon many benefits.

Preoperative deflation prior to mastopexy or augmentation-mastopexy is a safe and effective technique that offers the patient and surgeon many benefits.

History

As mastopexy operations began to evolve from the various methods of reduction mammoplasty, surgeons began to devise different techniques that emphasized minimizing the cutaneous scarring, while maximizing the vascular perfusion of the skin flaps and the nipple areolar complex. The greatest strides toward this end have come in the last century. Basic elements of mastopexy, such as transposition of the nipple areola and de-epithelialization to preserve perfusion and sensation, had been published by 1924.1–3 Dartigues addressed the issue of minimizing the cutaneous incisions used in mastopexy as well in 1924, submitting a method for correcting breast ptosis via a single infra-areolar vertical scar. The year before, Lötsch described a joining of techniques – adding a periareolar incision to a single vertical infra-areolar incision. This idea put forth by Lötsch caught the interest of Claude Lassus, who modified the technique from 1964 to 1980, developing what would ultimately become the classic vertical technique attributed to him for both mastopexy and reduction mammoplasty.4 In similar fashion, the vertical mastopexy and reduction techniques of Lassus adapted from Lötsch were again modified at the end of the 20th century. Lejour added the adjunctive use of suction-assisted lipectomy to the technique in 1994, which allowed easier contouring of the gland and stabilized the construct of the newly-shaped breast.5 Another variation of this technique was submitted by Hall-Findlay, who modified the placement of the nipple-areolar complex pedicle from the superior position to the medially-placed position and used no skin undermining or adjunctive liposuction.6 Hall-Findlay went on to further modify her technique for vertical mastopexy to use a laterally-based dermoglandular pedicle, which allowed her to auto-augment the breast by rotating the inferior and lateral glandular tissues beneath the nipple-areolar complex.7 Despite these several changes in technique that, among other things, minimize scarring, classic patterns that result in larger or more lengthy scars remain popular among many plastic surgeons, even today. The pattern of Wise, described in the mid-20th century, is a perfect example. Due to its ease of application, even in the most severe degrees of ptosis, the Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty remains popular, despite coming with the cost of a wide, inverted-T scar in addition to a periareolar scar.8 Other technical modifications, such as the use of mesh in the Góes technique, or the placement of a flap of autologous tissue beneath a loop of pectoralis major muscle by Graf and Biggs, have been added more recently to prolong the duration of the aesthetic result.9,10

Basic science/disease process

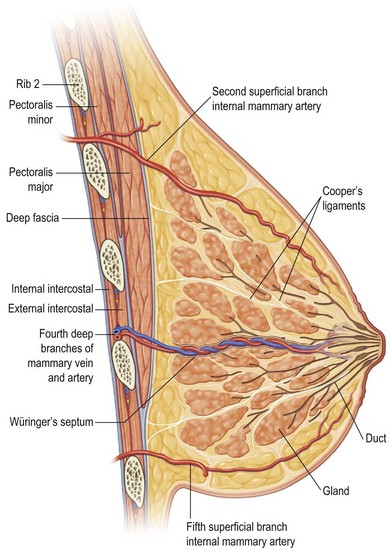

The pathophysiology of breast ptosis is multifaceted – but can be conceptualized as being the result of the combination of expansion and aging, or separately as a result of a congenital deformity. In its classic description, breast ptosis is the result of inadequate parenchyma or parenchymal maldistribution in the face of excess, lax skin and connective tissues. The ligaments described by Sir Astley Cooper run from the pectoralis muscular fascia, through breast parenchyma, and insert into the dermis (Fig. 7.1). Parenchymal changes with aging (accentuated by the case of the patient with an implant), weight changes in the obese, and pregnancy, are also accompanied by specific alterations in the integrity of Cooper’s ligaments, the breast’s fascial components, and the overlying skin. These processes essentially function as tissue expansion, as the parenchyma ebbs and flows with the tides of hormonal fluctuations in pregnancy or menopause, or with the weight fluctuations in the obese having lost massive amounts of weight, or with the expanded breast that is created with a breast implant. The skin becomes thin and stretched, and supporting structures, such as Cooper’s ligaments and the superficial and deep layers of the superficial breast fascia, lose their inherent elasticity. The breast parenchyma, once held in place on the chest wall by and within these structures, becomes mobile and descends with the constant pull of gravity. Adding the effects of time with aging only exacerbates these pathophysiologic changes. The loss of elastic recoil of the skin and connective tissue, coupled with involutional atrophy of the parenchymal mound, results in an unshapely, falling, and unaesthetic breast.

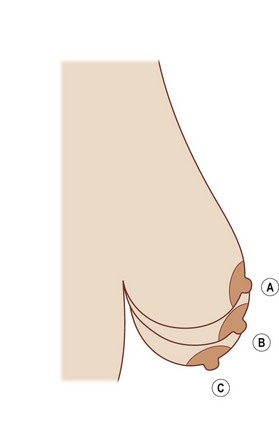

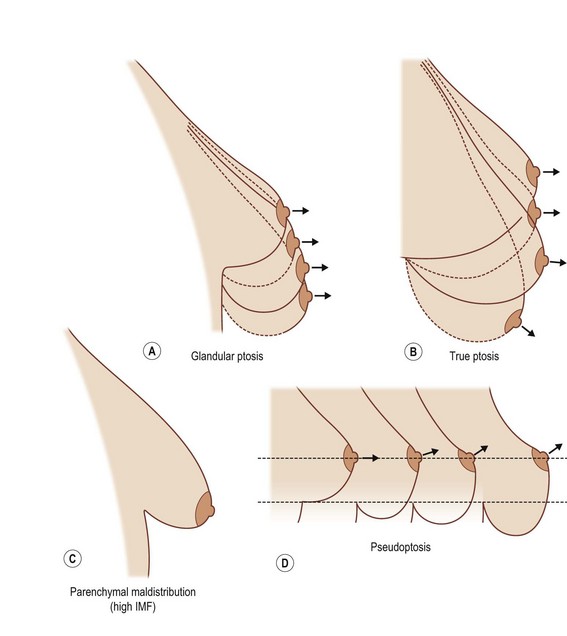

Breast ptosis in its various degrees is defined by its anatomic relationship to the inframammary fold. The original classification scheme for breast ptosis was set forth by Regnault,11 who in 1976 described the degrees of breast ptosis (Fig. 7.2). Grade I ptosis, or mild ptosis, was defined as having the nipple within 1 cm of the inframammary fold and being above the lower pole of the breast. Grade II, or moderate, breast ptosis exists when the nipple is 1–3 cm below the inframammary fold but still is above the lower pole of the breast. In grade III (severe) ptosis, the nipple is more than 3 cm below the inframammary fold and is situated below the lower breast contour. There is a fourth category of breast ptosis, commonly known as glandular or pseudoptosis, in which the nipple rests above the inframammary fold but the majority of breast tissue rests below and gives the appearance of ptosis.

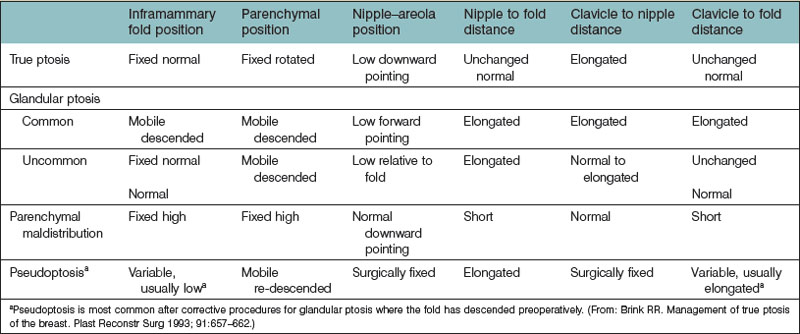

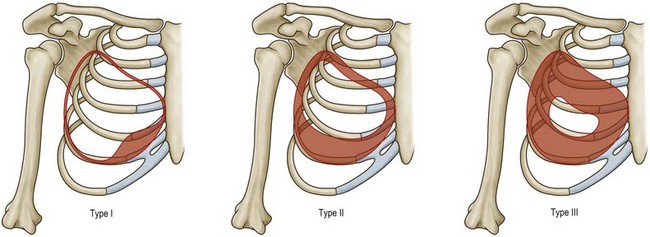

An additional caveat to the Regnault classification was submitted by Brink, which takes into account other causes of the ptotic breast, such as parenchymal maldistribution, and posits an algorithm by which they can be surgically addressed (Table 7.1, Fig. 7.3). One example of such parenchymal maldistribution is the tuberous breast deformity, also known as the tubular breast or constricted breast, which manifests as a high inframammary fold, hypoplastic lower pole, and nipple-areolar complex resting on the inferior-most aspect of the breast.12 Other classic features of the tuberous breast include herniation of the nipple-areolar complex as well as a constriction of the base of the breast.13 The tuberous breast deformity consists of a spectrum of different presentations to include some or all of these findings, the more severe cases representing the more challenging cases to correct (Fig. 7.4). Tuberous breasts can occur unilaterally, with the contralateral breast being unaffected, or can present to similar or vastly different degrees in bilateral cases. There are three classes of tuberous breast as described by Grolleau (Fig. 7.5). Type I deformities manifest as deficiency only in the lower medial quadrant, leaving the inferomedial shaped like an italic S and the inferolateral aspect comparably oversized. Both the inferomedial and inferolateral quadrants are deficient in the type II anomaly, leaving a paucity of skin in the infraareolar segment, which causes the areola to point downward. Finally, in a type III deformity, all four quadrants are deficient, and the breast base is constricted both horizontally and vertically.14 Von Heimburg describes a second classification scheme for the tuberous breast deformity (Table 7.2). In von Heimburg class I tuberous breasts, there is parenchymal hypoplasia of the inferomedial breast quadrant, similar to that described by Grolleau. The von Heimburg class II tuberous breast is also similar in description to Grolleau’s classification, with hypoplasia of the inferomedial and inferolateral breast parenchyma, and an adequate amount of periareolar skin. The third class of tuberous breast described by von Heimburg manifests as hypoplastic parenchyma inferomedially and inferolaterally, but with limited or inadequate periareolar skin. The fourth and final class of tuberous breast deformity described by von Heimburg is presents with hypoplastic parenchyma in all four breast quadrants.15 Various techniques, such as periareolar nipple-areolar reduction, radial scoring, dermoglandular flaps, autologous and alloplastic augmentation, and tissue expansion, among others, have been used for the correction of this deformity.

Fig. 7.3 (A–D) Different types of breast ptosis. IMF, inframammary fold.

(Redrawn after: Brink RR. Management of true ptosis of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993; 91:657–662.)

Table 7.2 von Heimburg’s tuberous breast classification

| Class | Anatomic features |

|---|---|

| von Heimburg class I | Hypoplasia of lower medial quadrant |

| von Heimburg class II | Hypoplasia of both lower quadrants with adequate areolar skin |

| von Heimburg class III | Hypoplasia of both lower quadrants with limited areolar skin |

| von Heimburg class IV | Hypoplasia of all quadrants |

(From von Heimburg D, Exner K, Kruft S, et al. The tuberous breast deformity: classification and treatment. Br J Plast Surg 1996; 49:339–345. Reprinted with permission from the British Association of Plastic Surgeons.)

Diagnosis and patient presentation

Patient evaluation

Preoperative breast imaging, in the form of high-resolution digital color photography is another important tool for documentation to demonstrate the degree of preoperative ptosis, as well as the degree of improvement postoperatively. The advent of three-dimensional imaging and computerized image-enhancing software has diversified the options for plastic surgeons to demonstrate to patients the implant sizes, asymmetries, and expected outcomes during consultations, as well as their postoperative improvement. Some of these concepts are covered in greater detail in Chapter 2.

Treatment/surgical technique

Periareolar techniques

In an effort to limit complications associated with periareolar mastopexy techniques, Spear et al. designed a series of rules to follow.16,17

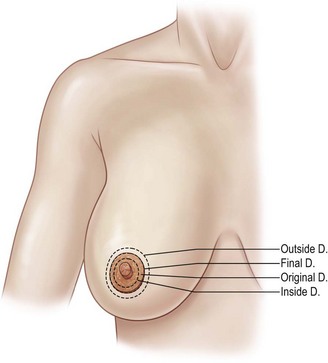

Rule 3: Dfinal =  (Doutside + Dinside). This final rule helps predict the final areolar size, which is particularly useful in asymmetry cases, as well as those in whom no round block suture is employed (Fig. 7.6).

(Doutside + Dinside). This final rule helps predict the final areolar size, which is particularly useful in asymmetry cases, as well as those in whom no round block suture is employed (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.6 Periareolar design guides as described by Spear et al. D, diameter.

(Modified from: Michelow BJ, Nahai F. Mastopexy. In: Achauer BM, Erikson E, Guyuron B, et al., eds. Plastic surgery: indications, operations and outcomes, Vol. 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2000.)

Periareolar Benelli mastopexy

The Benelli mastopexy technique is an extension of the donut mastopexy that was borne from dissatisfaction with the limitations of the simpler periareolar methods of mastopexy.18,19 The Benelli modifications allow the periareolar technique to be used to treat larger breasts with increasing degrees of ptosis. This technique can be combined with reduction techniques when necessary to ensure the best possible result while remaining true to the idea of a minimal scar. The fundamental concept behind the Benelli mastopexy is treatment of the skin and the gland as two separate components. The glandular tissue of the breast is accessed through the periareolar incision and separated from the overlying skin component. Superior, medial, and lateral dermoglandular flaps are created, with resection of intervening tissues and thinning of the flaps as is indicated for cases of macromastia. Glandular reassembly consists of reducing the glandular width, tightening the lower pole, and coning the breast construct by crisscrossing the medial and lateral dermoglandular flaps. The skin envelope is redraped over this newly formed glandular scaffold. A round block cerclage stitch is used as in the donut mastopexy to help control tension at the areola-skin junction. As can be seen, this technique allows precise shaping of the breast by the inverted T type of incision through the gland, while requiring no additional incisions in the skin.

Technique

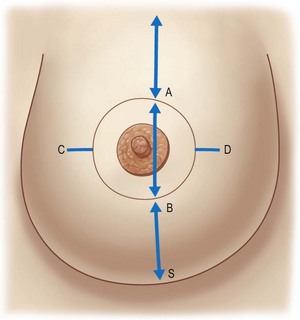

Preoperative marking is initiated by marking the midline and the estimated meridian of the newly shaped breast with the patient in the upright position. The new meridian is often medial to the breast meridian approximately 6 cm from the midline. The future superior border of the areola, point A, is marked on the meridian approximately 2 cm above the anterior projection of the inframammary fold. The future inferior border of the areola, point B, is marked with the patient supine approximately 5–12 cm above the inframammary fold on the basis of the estimated final breast volume and the expected skin retraction. The medial and lateral limits of the new areola, points C and D, are marked on the basis of estimates of the final breast volume. These limits are equidistant from the previously-marked meridian, and point C averages 8–12 cm from the midline (Fig. 7.7). The opposite breast is marked with reference to the already marked breast. The preoperative markings are verified by pinching together the superior and inferior points and then the medial and lateral points, ensuring that enough skin will remain to adequately cover the breast tissue without tension.

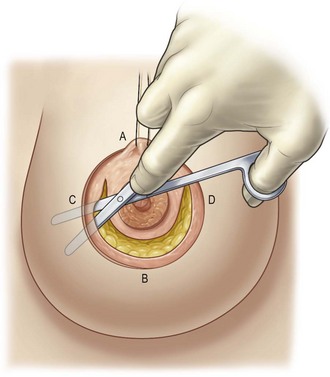

Infiltration with dilute saline (1000 mL), epinephrine (0.25 mg) and lidocaine 2% (20 mL) is performed subcutaneously in the area that will be detached. The ellipse and surrounding 3 cm is not infiltrated to preserve vascularity of the skin edges. The prepectoral area is also infiltrated. The desired areolar diameter is marked, and the periareolar ellipse is de-epithelialized. The de-epithelialized dermis is incised from the 2-o’clock to the 10-o’clock position. The dissection is extended toward the inframammary fold in the subcutaneous plane (Fig. 7.8). The dissection continues to the upper outer quadrant of the breast and becomes more superficial to preserve the vessels coming from the lateral thoracic artery.

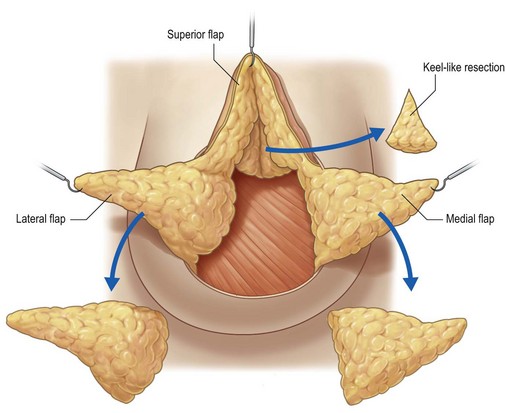

Glandular dissection is then initiated with a semicircular incision approximately 3 cm from the inferior areola edge to preserve innervation and blood supply to the areola. Dissection is continued to the prepectoral space in the avascular central space, preserving the peripheral blood supply. The inferior glandular flap is then cut vertically beyond the breast meridian up to the fascia. Four flaps will have thus been created: a superior dermoglandular flap supporting the areola, a glandular medial flap, a glandular lateral flap, and the detached skin flap (Fig. 7.9). These glandular flaps will be reassembled and repositioned to decrease the base of the breast, thus promoting the lifted appearance. If necessary, these flaps can be trimmed to reduce unwanted fullness. Volume reduction should be performed at the distal ends of the flaps to limit their length.

Once the appropriate resection is complete, the gland is initially lifted by placing a stitch in the glandular tissue of the superior flap and fixating this to the pectoralis fascia (Fig. 7.10). This should elevate the areola and cause an exaggerated convexity in the superior pole of the breast (Fig. 7.11). This exaggerated convexity will disappear within a few weeks secondary to gravity and the weight of the breast. Next, the medial and lateral flaps are folded over one another and sutured in place. Because most ptosis involves a lateral migration of the breast, the goal here is to medialize the breast. Therefore, the crisscross mastopexy is begun by rotating and folding the medial flap behind the areola, fixing its distal portion to the pectoralis muscle with superficial stitches (Fig. 7.12). The lateral flap is then crossed over and fixed to the medial flap (Fig. 7.13). The movement of these flaps reduces the base of the breast, forming a glandular cone on which to place the areola. If the gland requires no resection, a plication invagination can be performed to achieve an elevated conical breast shape (Fig. 7.14). The areola is fixated to the superior border of the ellipse through a 1-cm dermal incision made near the superior skin edge. This allows the knot to be buried and the areola to be supported without tension on the skin (Fig. 7.15). Support for the breast shape is achieved by full-breast lacing. Braided polyester suture on a long straight needle is used for the large inverted sutures along the underside of the gland. The superior stitch should pass through the superior dermoglandular flap, allowing control of the anterior projection of the nipple-areola complex. These full-breast lacing sutures should be applied without tension, their goal being to provide passive support of the newly formed conical breast. Tying these lacing sutures overly tight can result in glandular necrosis. The skin is redraped over the breast, and a round block cerclage stitch is passed in the deep dermis in purse-string fashion (Fig. 7.16). It is then cinched around a tube of the desired diameter, ensuring even distribution of the skin pleats. The block stitch is then tied, burying the knot in the previously formed dermal window. Further regulation of the projection of the areola is accomplished by an inverted dermoareolar stitch that takes a large vertical bite in the areola and a large horizontal bite in the dermal ellipse. This helps distribute any remaining deep pleats evenly around the areola. A diametrical transareolar U suture is placed to serve as a barrier and help prevent areola protrusion (Fig. 7.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree