Mastectomy for Breast Cancer

Shawna C. Willey

Donna-Marie E. Manasseh

Introduction

Breast cancer has been recorded in human history since approximately 3000 BCE, as documented in the Edwin Smith Papyrus (1). At that time, there was little that could be done to help individuals afflicted with this disease. Since then, the treatment of breast cancer has evolved with the increased understanding of the disease process and the development of newer methods to evaluate and treat breast cancer. In 1894, Halsted’s mastectomy approach was part of the surgical revolution that transformed the operative treatment of breast cancer, and it is the gold standard against which all subsequent treatments have been compared. Since Halsted’s time, the trend in the surgical management of breast cancer has been toward less extensive surgery. Breast-conserving surgery has become the preferred recommendation for patients who are acceptable candidates. There are, however, still a significant number of patients who are not candidates for or do not want breast-conserving surgery, so mastectomy remains an important treatment modality for breast cancer. Mastectomy rates vary from 30% to 50%, with some of the variation attributed to practice patterns in different geographic regions. There has been a reported increase in the number of mastectomies being performed over the last decade (2). For any patient with breast cancer (invasive or noninvasive), the option of mastectomy must be offered and discussed in detail. This chapter provides information about invasive breast carcinoma and its treatment. To that end, the procedure of a mastectomy is discussed.

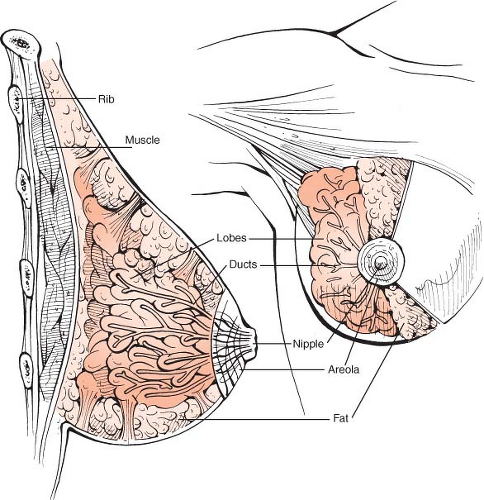

Breast cancer comprises a number of different varieties. It arises in the terminal ductal-lobular unit (Fig. 8.1). The vast majority of breast cancers arise from the epithelial lining of the duct or the lobule and can be either invasive (infiltrating ductal carcinoma or infiltrating lobular carcinoma) or noninvasive (ductal carcinoma in situ or lobular carcinoma in situ [LCIS]). Although LCIS is not treated as cancer, it is considered a marker for increased risk and is included in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging. This chapter deals with mastectomy as treatment for patients with invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ.

Staging of Breast Cancer

The staging system for breast cancer has undergone many revisions with the development of new technology and a greater understanding of the disease process. Here we present the most recent 2003 revision of the staging system by the AJCC (3) (Table 8.1). It is a clinical and pathologic system based on the TNM (tumor, node, and metastasis) classification. This staging system takes into account sentinel node status, immunohistochemistry staining, and the presence of micrometastases.

Primary Tumor (T)

TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0: No evidence of primary tumor

Tis: Carcinoma in situ (intraductal carcinoma, lobular carcinoma in situ, or Paget’s disease of the nipple with no associated invasion of normal breast tissue)

Tis (DCIS): Ductal carcinoma in situ

Tis (LCIS): Lobular carcinoma in situ

Tis (Paget’s): Paget’s disease of the nipple with no tumor

Note: Paget’s disease associated with a tumor is classified according to the size of the tumor.

T1: Tumor less than or equal to 2.0 cm in greatest dimension

T1mi: Microinvasion less than or equal to 0.1 cm in greatest dimension

T1a: Tumor greater than 0.1 cm but less than or equal to 0.5 cm in greatest dimension

T1b: Tumor greater than 0.5 cm but less than or equal to 1.0 cm in greatest dimension

T1c: Tumor greater than 1.0 cm but less than or equal to 2.0 cm in greatest dimension

T2: Tumor greater than 2.0 cm but less than or equal to 5.0 cm in greatest dimension

T3: Tumor greater than 5.0 cm in greatest dimension

T4: Tumor of any size with direct extension to

(a) chest wall or

(b) skin, only as described here:

T4a: Extension to chest wall, not including pectoralis muscle

T4b: Edema (including peau d’orange) or ulceration of the skin of the breast, or satellite skin nodules confined to the same breast

T4c: Both T4a and T4b

T4d: Inflammatory carcinoma

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)

NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed (e.g., previously removed)

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

N1: Metastasis to movable ipsilateral level I, II axillary lymph node(s)

N2: Metastasis in ipsilateral level I, II axillary lymph node(s) fixed or matted, or in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary nodes in the absence of clinically evident lymph node metastasis

N2a: Metastasis in ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes fixed to one another (matted) or to other structures

N2b: Metastasis only in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary nodes and in the absence of clinically evident axillary lymph node metastasis

N3: Metastasis in ipsilateral infraclavicular (level III axillary) lymph node(s) with or without level I, II axillary lymph node involvement, or in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary lymph node(s) and in the presence of clinically evident level I, II axillary lymph node metastases; or metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph node(s) with or without axillary or internal mammary lymph node involvement

N3a: Metastases in ipsilateral infraclavicular lymph node(s)

N3b: Metastases in ipsilateral internal mammary lymph node(s) and axillary lymph node(s)

N3c: Metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph node(s)

Note: Clinically detected is defined as detected by imaging studies (excluding lymphoscintigraphy) or by clinical examination and having characteristics highly suspicious for malignancy.

Table 8.1 American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage Groupings | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pathologic Classification (Pn)

pNX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed (e.g., not removed for pathologic study or previously removed)

pN0: No regional lymph node metastases identified histologically

Note: Isolated tumor cell clusters (ITC) are defined as small clusters of cells not greater than 0.2 mm, or single tumor cells, or a cluster of fewer than 200 cells in a single histologic cross-section. ITCs may be detected by routine histology or by immunohistochemical (IHC) methods. Nodes containing only ITCs are excluded from the total positive node count for purposes of N classification but should be included in the total number of nodes evaluated.

pN0(i–): No regional lymph node metastases histologically, negative IHC

pN0(i+): Malignant cells in regional lymph node(s) no greater than 0.2 mm (detected by H&E or IHC including ITC)

pN0(mol–): No regional lymph node metastases histologically, negative molecular findings (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR])

pN0(mol+): Positive molecular findings (RT-PCR), but no regional lymph node metastases detected by histology or IHC

Note: Classification is based on axillary lymph node dissection with or without sentinel lymph node dissection. Classification based solely on sentinel lymph node dissection without subsequent axillary lymph node dissection is designated (sn) for “sentinel node”; for example, pN0(I+) (sn).

pN1: Micrometastases; or metastases in 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes; and/or in internal mammary nodes with metastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detected

pN1mi: Micrometastases (greater than 0.2 mm and/or more than 200 cells, but none greater than 2.0 mm)

pN1a: Metastases in 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes, at least one metastasis greater than 2.0 mm

pN1b: Metastases in internal mammary nodes with micro-metastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detected

pN1c: Metastases in 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detected

pN2: Metastases in 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes; or in clinically detected internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases

pN2a: Metastases in 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes (at least one tumor deposit greater than 2.0 mm)

pN2b: Metastases in clinically detected internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases

pN3: Metastases in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes; or in infra-clavicular (level III axillary) lymph nodes; or in clinically detected ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of 1 or more positive level I, II axillary lymph nodes; or in more than 3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detected; or in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes

pN3a: Metastases in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes (at least one tumor deposit greater than 2.0 mm); or metastases to the infraclavicular (level III axillary lymph) nodes

pN3b: Metastases in clinically detected*** ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of 1 or more positive axillary lymph nodes; or in more than 3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detected

pN3c: Metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph node(s)

Note: Clinically apparent is defined as detected by imaging studies (excluding lymphoscintigraphy) or by clinical examination. Not clinically apparent is defined as not detected by imaging studies (excluding lymphoscintigraphy) or by clinical examination.

Distant Metastasis (M)

M0: No clinical or radiographic evidence of distant metastases

M1: Distant detectable metastases as determined by classic clinical and radiographic means and/or histologically proven larger than 0.2 mm

cMo(i+): No clinical or radiographic evidence of distant metastases, but deposits of molecularly or microscopically detected tumor cells in circulating blood, bone marrow or other non-regional nodal tissue that are no larger than 0.2 mm in a patient without symptoms or signs of metastases

Mastectomy

Historical Perspective

One of the earliest recorded operative approaches to the treatment of breast cancer dates to the 18th century when Jean Louis Petit advocated removal of the breast, pectoral muscles, and axillary lymph nodes to treat the disease (4). Since then, several operations have been described for the treatment of breast cancer. Most notably, in 1894, William Halsted described what is referred to today as the “Halstedian” radical mastectomy. In his landmark study, Halsted described his surgical attack on breast cancer. He stated, “the suspected tissue should be removed in one piece” (5). This is done by complete en bloc resection of the breast with the pectoralis major muscle and regional lymphatics. With this approach, Halsted achieved a decrease in local recurrence rates of 6% and regional recurrence rates of 22% from rates of 51% to 82% for surgeons of his day (5,6,7). Approximately 10 days after Halsted’s study appeared in print, Willy Meyer published his technique for radical mastectomy (8). Although it was similar to Halsted’s approach, there are some differences that warrant mentioning. In Halsted’s approach, the pectoralis major muscle with the overlying breast tissue was dissected from the underlying sternum and the chest wall prior to removal of the axillary contents. In Meyer’s approach the axilla was dissected prior to the resection of the breast and pectoral muscles. In addition, Halsted simply divided the pectoralis minor muscle and left it in situ, whereas Meyer advocated removal of the pectoralis minor as well. Both Halsted and Meyer used vertical incisions; however, Halsted regularly sacrificed much more skin (taking as much skin as possible on all sides of the tumor) than in Meyer’s approach. A skin graft was often required to cover the chest wall defect with Halsted’s approach. In both Halsted’s and Meyer’s approaches, all three nodal levels from the latissimus dorsi laterally to the thoracic outlet medially were removed (8,9). Both approaches sacrificed the long thoracic nerve and the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle en bloc with the axillary contents.

These approaches, believed necessary at the time as evidenced by the substantial decrease in recurrence rates with these operations, left women disfigured and with significant disabilities such as “winged scapula,” lymphedema, and shoulder fixation. There have since been several modifications in the surgical treatment of the breast in an effort to decrease the morbidity associated with these operations while preserving the improved disease-free survival that had been noted with Halsted’s approach.

In the 1940s, Patey (10,11) advocated preservation of the pectoralis major muscle. It was noted that this procedure was equivalent in terms of local relapse rate and overall survival to the results for patients treated with the previously described standard radical mastectomy. Haagensen (12), in the early 1970s, advocated preservation of the long thoracic nerve to avoid the “winged

scapula” disability. He stated that it was unnecessary to remove this nerve to achieve adequate surgical treatment of breast cancer. In the 1960s, Auchincloss (13) and Madden (14), in contrast to Patey, advocated preservation of both pectoralis major and minor muscles. With this modification, only level I and level II nodes were easily accessible, and the dissection of level III nodes was restricted. Auchincloss (13) further stated that removal of level III nodes was necessary only if they were clinically involved because of the high recurrence rate if positive nodes were left in place. The Auchincloss modification of the radical mastectomy is most consistent with the modified radical mastectomy of today.

scapula” disability. He stated that it was unnecessary to remove this nerve to achieve adequate surgical treatment of breast cancer. In the 1960s, Auchincloss (13) and Madden (14), in contrast to Patey, advocated preservation of both pectoralis major and minor muscles. With this modification, only level I and level II nodes were easily accessible, and the dissection of level III nodes was restricted. Auchincloss (13) further stated that removal of level III nodes was necessary only if they were clinically involved because of the high recurrence rate if positive nodes were left in place. The Auchincloss modification of the radical mastectomy is most consistent with the modified radical mastectomy of today.

Further modification of the modified radical mastectomy occurred with the development of the total mastectomy. This procedure preserves both pectoralis muscles and the axillary lymph nodes. The rationale for this modification stems from the popularization of the hypothesis that breast cancer is a systemic disease (15). Based on this hypothesis, the regional nodal dissection is unnecessary in the clinically negative axilla because it is unlikely to affect survival.

Several retrospective and prospective studies (16,17,18) sought to prove the hypothesis that breast cancer is a systemic disease early in its course. Most notable of these is the prospective randomized study by Fisher and the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). In the 1970s, NSABP B-04 (15) compared total mastectomy with and without axillary radiation to standard radical mastectomy. This study, which demonstrated no statistically significant difference in disease-free survival between the study arms, supported the notion that aggressive surgical management does not change survival in a disease that is systemic and heralded the introduction of a more minimal approach to the surgical treatment of breast cancer. Included in this minimalist approach is preservation of muscles, lymph nodes, and even skin. Toth and Lappert first used the term skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) in 1991 (19). They described preoperative planning of mastectomy incisions in an attempt to maximize skin preservation and facilitate immediate breast reconstruction. Skin-sparing mastectomy (in which the nipple-areola complex and a minimal amount of skin are removed) is commonly used in patients who desire immediate reconstruction. Preservation of the inframammary fold (IMF) and the native skin envelope enhances the aesthetic result of breast reconstruction. Taking the minimalist approach even further is total skin-sparing mastectomy (nipple-sparing mastectomy), which is under investigation in the prophylactic setting as well as for selected patients with breast cancer. Similarly, breast conservation has evolved as part of the trend toward less surgery for breast cancer. A brief discussion is presented here for reference, but details are presented in Chapter 10.

Breast conservation involves removal of the primary tumor with an adequate margin of normal breast parenchyma. It is followed by radiation therapy in order to provide equivalent survival rates to that achieved with mastectomy as demonstrated in the NSABP B-06 (20) and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer trials (21). Breast-conserving surgery is also referred to as lumpectomy, partial mastectomy, and segmental mastectomy. Any woman is a candidate provided the following criteria are met:

The removal of the primary breast tumor with an adequate margin of normal breast parenchyma is accomplished while maintaining an acceptable cosmetic result.

The patient can tolerate the recommended radiation therapy regimen.

Positive axillary nodes on clinical or pathologic examination are not a contraindication to breast conservation.

Indications for Mastectomy

Almost all women with breast cancer are candidates for mastectomy. The specific type of mastectomy performed relies on the presentation of the patient and her disease. Differentiation between total mastectomy and skin-sparing mastectomy is a somewhat arbitrary definition, as the defining factor between the two is the amount of skin left intact to accomplish reconstruction. The Halstedian mastectomy is of historic interest today. There are occasions when excision of muscle invaded by tumor is performed en bloc during a mastectomy; however, with the availability of multimodality therapy, radiation therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy are used to improve outcome in those patients with locally advanced disease.

Indications for mastectomy are as follows:

The presence of two or more primary tumors in separate quadrants or diffuse malignant calcifications

Invasive carcinoma with an extensive DCIS component

Persistent positive margins after multiple surgical attempts with partial mastectomy

Recurrence in a breast previously treated with partial mastectomy and radiation

Tumor size relative to breast size that does not allow for breast conservation and an acceptable cosmetic outcome

Contraindication to receiving radiation treatment to the breast (collagen-vascular disease, pregnancy)

Patient preference in those considered at high risk (gene mutation carriers for BRCA1/BRCA2 or strong family history), in which case bilateral mastectomy may be considered

The indications for modified radical mastectomy are similar to those for total mastectomy as it relates to the treatment of disease in the breast. The difference lies in the surgical approach to the axilla. If a patient has biopsy-proven involvement of an axillary lymph node or circumstances that exclude her from undergoing a sentinel node biopsy, then an axillary dissection in conjunction with the mastectomy is performed (i.e., a modified radical mastectomy).

Anatomic Considerations

The female breast is an apocrine gland arising from a skin appendage, a so-called “modified sweat gland.” It is enclosed between the superficial and deep layers of the superficial fascia of the anterior abdominal wall. The superficial layer is a very delicate, but definite structure that can be seen in most patients. It is not as well defined in fatty breasts and along the IMF (22). Large vessels lie deep to this plane that send vertical branches to the subdermal plexus (23).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree