Managing Complications of Augmentation Mammaplasty

Neal Handel

Breast implants were first introduced in the United States nearly 50 years ago (1). Since that time they have been widely used for postmastectomy reconstruction, treatment of congenital anomalies, breast augmentation, and correction of ptosis. About two million American women currently have breast implants (2,3), the vast majority of which have been used for cosmetic purposes. The overall satisfaction rate among augmentation patients is high (4,5), but implants are associated with a significant incidence of risks and side effects (6). In spite of earlier concerns, it has now been proven that there is no relationship between implants and breast cancer, immune disorders, or systemic illnesses (7,8). However, recent studies of implant recipients have documented that local complications are relatively common and reoperation not infrequent (9,10). The Mentor Core Study of silicone implants used for primary breast augmentation revealed a reoperation rate of 15% within 3 years; the Allergan Breast Augmentation Core Study documented a reoperation rate of 24% at 4 years. Because of the significant incidence of local implant-related complications, plastic surgeons must be familiar with the diagnosis and management of these conditions.

Over the last five decades, a wide variety of implant types and styles have been introduced. There have been variations in shell thickness, filler materials, implant configuration, surface texture, and other characteristics. Some local complications arising from breast implants are specific to the particular type of device; most, however, are common to all breast implants.

Although there is some overlap, it is convenient to divide implant-related complications into those that generally occur “early” (within days or weeks of implantation) and those that typically occur “late” (months, years, or even decades later). Early postoperative complications include fluid accumulations such as seromas and hematomas, infections, galactorrhea, Mondor’s disease, and breast asymmetry. Implant malposition (which may express itself in a variety of manifestations) and the “double-bubble” deformity can both occur either as early or as delayed phenomena. Late complications include palpability and rippling, capsular contracture, breast deformity and discomfort due to subpectoral positioning, implant exposure and extrusion, silicone gel bleed, shell disruption with gel extravasation, saline implant deflation, and interference with mammography.

Early Complications (Days or Weeks After Surgery)

Seroma and Hematoma

Excessive accumulation of blood or serum in the periprosthetic space during the early postoperative period is not unusual. The Allergan Core Study revealed a seroma rate of 1.3% following primary augmentation. If a breast becomes significantly more swollen than expected but is not painful, tender, or ecchymotic, it is usually due to a seroma. A fluid wave may be elicited on physical examination. Diagnosis can be confirmed by ultrasonography. Treatment is conservative: avoiding trauma to the breast and minimizing movement of the upper extremity on the affected side. This will hasten reabsorption of the fluid. A brassiere or elastic mammary support is worn day and night to immobilize the breast, and an arm sling may be employed to reduce movement of the upper extremity. The seroma will usually resolve spontaneously within a few weeks and does not appear to increase the risk of contracture or other complications. It is inadvisable to attempt needle aspiration of a seroma because of the risk of damaging the implant or introducing infection. In rare cases of a persistent or refractory seroma, it may be necessary to explore the pocket and insert a drain.

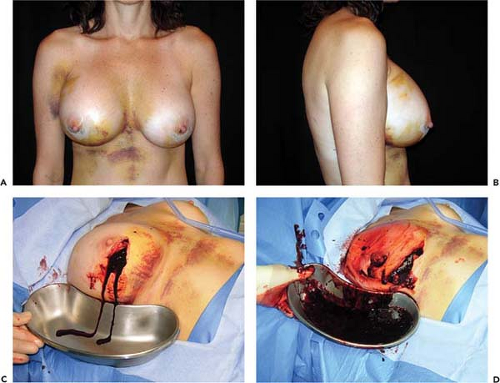

The reported frequency of hematomas after breast augmentation is in the range of 1% to 3% (11,12). In the Mentor Core Study the hematoma rate was 2.6%; in the Allergan Core Study it was 1.6%. Typically, hematomas are characterized by swelling of the affected breast, firmness, pain, tenderness, and excessive ecchymosis (Fig. 124.1). Treatment depends on the severity and anatomic location of the bleeding. If a small amount of blood has accumulated superficially, beneath the operative incision, it can easily be drained by opening a short segment of the wound. If there is minimal intraparenchymal bleeding and the breast is stable, conservative treatment, consisting of observation, immobilization, and application of moist heat, is indicated. If there has been accumulation of blood in the implant pocket (periprosthetic space), it is advisable to explore the breast and drain the hematoma. In the majority of cases a discreet bleeder is not identified due to clotting by tamponade. The blood is evacuated, the pocket thoroughly irrigated, and the implant reinserted. A surgical drain is optional. Patients with undrained hematomas after augmentation mammaplasty are at increased risk of developing capsular contracture (13) and infection.

Infection

Infection occurs following augmentation mammaplasty in 1% to 4% of cases (14,15,16). In the Mentor Core Study the infection rate was 1.5% after primary augmentation. Symptoms of infection usually manifest during the first postoperative week, but delayed infections have been reported months or even years after augmentation (17). The risk of infection does not appear to be related to the location of the operative incision, surface characteristics of the implant (smooth vs. textured) filler material (saline vs. gel), or implant position (submammary vs. subpectoral) (18). Local symptoms include excessive swelling, pain, tenderness, erythema, warmth of the breast,

and sometimes drainage from the incision (Fig. 124.2). The axillary lymph nodes may be enlarged and tender, and occasionally there are systemic manifestations such as fever or chills and an elevated leukocyte count. Diagnosis and treatment are usually based on clinical findings because wound exudate is rarely available for culture. In rare cases, infection may cause thinning of tissues and even erosion of the skin, resulting in a fistula that communicates with the periprosthetic space (Fig. 124.3).

and sometimes drainage from the incision (Fig. 124.2). The axillary lymph nodes may be enlarged and tender, and occasionally there are systemic manifestations such as fever or chills and an elevated leukocyte count. Diagnosis and treatment are usually based on clinical findings because wound exudate is rarely available for culture. In rare cases, infection may cause thinning of tissues and even erosion of the skin, resulting in a fistula that communicates with the periprosthetic space (Fig. 124.3).

Once infection is diagnosed, treatment should be initiated immediately. If the process is localized and superficial, such as a suture abscess, opening, irrigating, and packing the wound may be sufficient. If the process is more generalized, systemic antibiotics are indicated. When there is cellulitis without involvement of the periprosthetic space, oral antibiotics are often effective. Most infections are caused by gram-positive organisms, usually Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus types A and B. Less commonly, enteric bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or even atypical Mycobacteria, are the causative agents (19); when these are the responsible organisms onset of infection is usually delayed. In the absence of a specific culture diagnosis, broad-spectrum antibiotics are used empirically. In recent years the incidence of community-based methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has been steadily on the rise. For this reason, when treating breast implant infections empirically, many infectious disease specialists recommend a broader combination of antibiotic therapy (to cover the usual pathogens as well as MRSA). Ideally, “surveillance cultures” are obtained simultaneously with initiation of antibiotic coverage. The patient’s armpit and nose may be swabbed for culture and sensitivity studies (with a single swab) to determine if the patient is an MRSA carrier. Pending the culture results, it is recommended administering amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) in non–penicillin-allergic patients to cover Streptococcus and sensitive Staphylococcus and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (Bactrim) in non–sulfa-allergic patients to cover MRSA. In patients with a mild allergy to penicillin (e.g., skin rash), cephalexin (Keflex) may be substituted for Augmentin in conjunction with Bactrim. In sulfa-allergic patients, alternative drugs (e.g., clindamycin, doxycycline) may be substituted for Bactrim. In patients with more aggressive infections it may be prudent to start intravenous

therapy; one recommended regimen is vancomycin (administered for 1 to 3 days, depending on the clinical response) in conjunction with ceftriaxone (Rocephin). There is some evidence that infection, even when treated successfully, significantly increases the risk of subsequent contracture (14).

therapy; one recommended regimen is vancomycin (administered for 1 to 3 days, depending on the clinical response) in conjunction with ceftriaxone (Rocephin). There is some evidence that infection, even when treated successfully, significantly increases the risk of subsequent contracture (14).

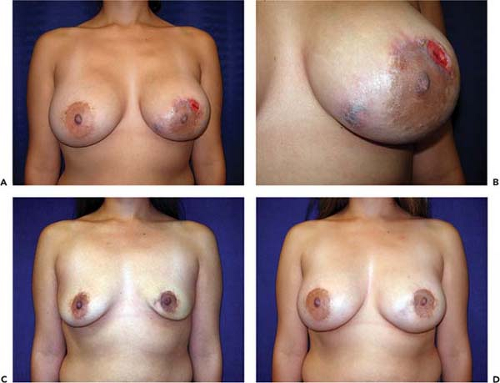

If the implant pocket (periprosthetic space) is involved, eradication of infection is difficult, if not impossible, unless the implant is removed. Sometimes symptoms are suppressed while the patient is on antibiotics but reappear when antibiotics are discontinued. In these cases, the most efficient approach is explantation and drainage of the pocket. The area is allowed to heal, and after about 3 months, when inflammation has subsided and tissues have softened, a new implant may be inserted (Fig. 124.4). Spear et al. (20) published specific guidelines for salvaging infected implants in selected cases; if implant exposure is threatened (or has actually occurred), local or distant flaps can be used for salvage. Sometimes such valiant efforts are justified. However, these extraordinary measures may be costly, time consuming, and extremely inconvenient to patients. In patients who develop severe infections after breast augmentation it is often more expedient simply to remove the implant and wait an adequate period of time before replacing it. If an implant is left in place and infection allowed to progress unabated, it could lead to a disastrous result, with extensive tissue loss and permanent deformity (Fig. 124.5).

Mondor’S Disease

Mondor’s disease, thrombophlebitis of the superficial superior epigastric vein, occurs postoperatively in less than 1% of augmentation mammaplasty patients (21). Usually this complication manifests during the first several weeks postoperatively. It is most common following an inframammary operative incision. Patients usually present with a slightly tender inflamed cordlike structure extending caudally from the inframammary fold (Fig. 124.6). The thrombus poses no risk of embolization. Patients are instructed to apply moist heat to the area. In very symptomatic cases, oral anti-inflammatory medications may be indicated. The condition is self-limited and usually resolves within 4 to 6 weeks (22). Mondor’s disease has no permanent sequelae.

Galactocele and Galactorrhea

Galactocele (localized collection of milk) and galactorrhea (discharge of milk from the nipple or surgical incisions) after

breast augmentation or other breast operations are infrequent (23,24). Drainage usually starts within several days of surgery and may be copious (25). Lactation is believed to occur secondary to prolactin elevation in the presence of falling estrogen and progesterone levels. Surgery may stimulate thoracic nerve endings, sending signals to the hypothalamus and pituitary, which cause increased prolactin secretion. Collections of milk may be significant enough to warrant aspiration or surgical drainage; antibiotics should be instituted. The process may last for only a few days, but, reportedly, can persist for months or even years (26). Administration of bromocriptine (Parlodel) or cabergoline (Dostinex), both of which suppress prolactin secretion, has proven helpful in managing postsurgical galactorrhea.

breast augmentation or other breast operations are infrequent (23,24). Drainage usually starts within several days of surgery and may be copious (25). Lactation is believed to occur secondary to prolactin elevation in the presence of falling estrogen and progesterone levels. Surgery may stimulate thoracic nerve endings, sending signals to the hypothalamus and pituitary, which cause increased prolactin secretion. Collections of milk may be significant enough to warrant aspiration or surgical drainage; antibiotics should be instituted. The process may last for only a few days, but, reportedly, can persist for months or even years (26). Administration of bromocriptine (Parlodel) or cabergoline (Dostinex), both of which suppress prolactin secretion, has proven helpful in managing postsurgical galactorrhea.

Asymmetry of the Inframammary Fold

Asymmetry of the inframammary fold is a distressing complication after augmentation mammaplasty. In the Allergan Core Study asymmetry was noted in 3.2% of patients. If asymmetry becomes apparent immediately after surgery, it probably results either from excessive or inadequate pocket dissection on one side. Early implant malposition sometimes responds to conservative measures. If the upper pole of the breast is too “high,” patients are instructed to compress the implant downward. A circumferential elastic Velcro strap is applied around the upper pole of the breasts and worn continuously. Sometimes, these simple measures will enable the implant to “settle” into the correct position. If the implant is too “low,” an effort may be made to immobilize the implant in the proper location so the flap can reattach to the chest wall and eliminate the potential space. This may be accomplished by having the patient wear a snug underwire bra continuously for 6 weeks. By that time, any fluid around the implant should reabsorb, and the tissue surfaces have time to adhere. Sometimes, these strategies fail and asymmetry persists, or patients present with asymmetry long after original augmentation. In these cases an open approach is necessary to achieve permanent correction.

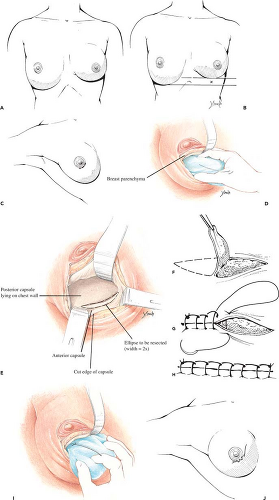

If the inframammary fold is too high, surgical correction consists simply of inferior capsulotomy to deepen the pocket to the appropriate level (Fig. 124.7). If the fold is too low, surgical correction is a bit more involved. One well-established technique for raising the fold is “capsulorrhaphy” (27,28) (Fig. 124.8). Prior to surgery the difference between the levels of the inframammary folds is determined. This is accomplished with the patient in the standing position with the arms adducted. A horizontal line is drawn at the level of the lower fold across to the opposite side of the thorax. The distance between this line and the “normal” fold indicates how far the lower fold must be raised. Alternatively, the distance from the nipple to the fold may be measured on the two sides and the difference calculated.

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia; local anesthetic containing epinephrine is infiltrated into the area of the proposed incision. If the patient had prior augmentation through a transareolar, periareolar, or inframammary incision, the old scar can be used for access. If the patient was previously augmented through the axillary or umbilical approach, a new incision is made in the periareolar or inframammary location. The wound is deepened through the breast parenchyma with the electrocautery to minimize bleeding and prevent accidental puncture of the implant. The capsule is then opened with the electrocautery, exposing the implant. The prosthesis is carefully removed and set aside in a basin containing antibiotic solution or dilute Betadine (povidone-iodine) (Purdue Pharma L.P., Stamford, CT).

The inferior portion of the cavity is visualized and a marking pen used to draw an ellipse designating the area to be resected. The ellipse has a width twice the distance the fold is to be raised and extends the length of the inframammary crease. Excision of the elliptical segment of the capsule is accomplished with the electrocautery. When the anterior flap is allowed to fall into approximation with the chest wall, the raw surfaces will be crescent shaped and have a width equal to the distance the fold is being raised. After hemostasis is obtained, the cut edges of the anterior and posterior capsule are sutured

together with a running locked nonabsorbable (nylon, Prolene, Ethibond) suture. The implant (or preferably a “sizer”) is inserted and the patient elevated to the semi-sitting position to ascertain adequacy of correction and desired symmetry. If necessary, electrocautery dissection can be used to modify the fold as needed (by cutting through the anterior capsule adjacent to the suture line) to achieve the desired contour. In cases in which the implant is in the subpectoral position, conversion to a submammary pocket is also a useful adjunct when adjusting the level of the fold. With reintroduction of silicone gel implants, patients with an adequate layer of soft tissue (2 cm or greater pinch of upper pole of the breast) generally get excellent results with gel-filled implants in the submammary position. If the implant is left into the subpectoral position, the downward and lateral force vector applied to the prosthesis every time the pectoral is muscle is activated tends to displace the implant laterally and inferiorly. This sometimes disrupts a successful repair. Once the desired symmetry has

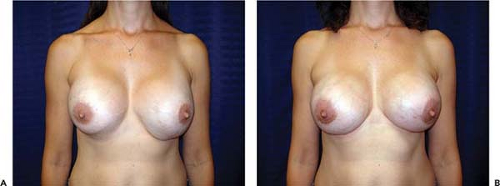

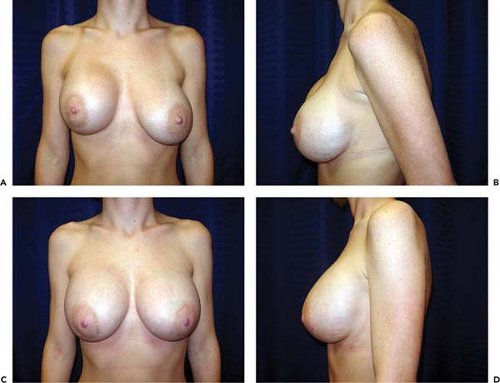

been achieved, the implant is reinserted and the operative incision is closed in the customary fashion. The newly defined inframammary fold can be reinforced by creating an “underwire bra” fabricated of strips of 0.5-inch paper tape secured by Mastisol. A light figure-of-eight pressure wrap is applied. Patients are instructed to wear snug-fitting underwire bras continually for 6 weeks after the repair to ensure proper healing (Fig. 124.9). The problem of a low inframammary fold may, of course, be only unilateral or may be bilateral (Fig. 124.10).

together with a running locked nonabsorbable (nylon, Prolene, Ethibond) suture. The implant (or preferably a “sizer”) is inserted and the patient elevated to the semi-sitting position to ascertain adequacy of correction and desired symmetry. If necessary, electrocautery dissection can be used to modify the fold as needed (by cutting through the anterior capsule adjacent to the suture line) to achieve the desired contour. In cases in which the implant is in the subpectoral position, conversion to a submammary pocket is also a useful adjunct when adjusting the level of the fold. With reintroduction of silicone gel implants, patients with an adequate layer of soft tissue (2 cm or greater pinch of upper pole of the breast) generally get excellent results with gel-filled implants in the submammary position. If the implant is left into the subpectoral position, the downward and lateral force vector applied to the prosthesis every time the pectoral is muscle is activated tends to displace the implant laterally and inferiorly. This sometimes disrupts a successful repair. Once the desired symmetry has

been achieved, the implant is reinserted and the operative incision is closed in the customary fashion. The newly defined inframammary fold can be reinforced by creating an “underwire bra” fabricated of strips of 0.5-inch paper tape secured by Mastisol. A light figure-of-eight pressure wrap is applied. Patients are instructed to wear snug-fitting underwire bras continually for 6 weeks after the repair to ensure proper healing (Fig. 124.9). The problem of a low inframammary fold may, of course, be only unilateral or may be bilateral (Fig. 124.10).

An alternative to capsulorrhaphy for correction of asymmetric folds or other manifestations of implant malposition is the use of capsular flaps. Such flaps can be elevated and advanced or transposed to reconfigure the pocket and reposition the implant (29).

Implant Malposition

The incidence of implant malposition is not precisely known. In the Allergan Core Study implant malposition was identified in 4.1% of breast augmentation patients by the end of 4 years. Implants of course may be malpositioned too far laterally or too far medially. When the pocket extends too far laterally, the implant can easily become displaced beyond the anterior axillary line, causing flatness of the breast in the parasternal region and excessive lateral fullness. This deformity is most apparent with the patient lying supine (Fig. 124.11) and may be more frequent after transaxillary augmentation. Conservative measures aimed at correcting lateral displacement are usually unsuccessful. The most direct approach is to explore the breast and reduce the dimensions of the pocket by capsulorrhaphy. Under direct visualization, the appropriate segment of scar tissue capsule is resected; the cut edges are approximated and sutured to one another to eliminate the lateral extension of the pocket. The technique is similar to that used to correct inferior malposition of an implant. Conversion from the subpectoral to the submammary plane (when there is adequate soft tissue coverage) helps to maintain the correction by eliminating lateral vector forces generated when the pectoral

muscle contracts (Fig. 124.12). With the reintroduction of silicone gel implants into general use a much larger proportion of patients are candidates for submammary positioning of their implants.

muscle contracts (Fig. 124.12). With the reintroduction of silicone gel implants into general use a much larger proportion of patients are candidates for submammary positioning of their implants.

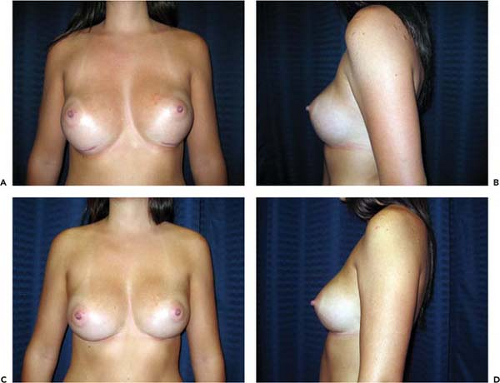

If the implant pocket extends too far medially, it creates the disturbing condition known as synmastia (30). The term synmastia can be applied to any situation in which the breast implant crosses the midline, even if it is only on one side. Typically, patients present with confluence of the breasts at the midline and loss of normal cleavage (Fig. 124.13). Certain factors seem to contribute to the likelihood of this complication, including large implants, subpectoral placement, and multiple successive operations to increase implant size (31).

If the implants are submammary, one solution is to replace them in the subpectoral position (Fig. 124.14). The medial attachment of the pectoral muscle serves as a “restraining ligament” to prevent the implant from shifting too close to the midline. It is ordinarily necessary to divide partially the origins of the pectoral muscle to develop a submuscular pocket of adequate size. Care should be taken not to extend this dissection too far medially. The potential space superficial to the pectoral muscle (the preexisting submammary pocket) is eliminated by placing sutures between the lateral edge of the pectoral muscle and the overlying scar tissue capsule. This potential space must be permanently closed because if it is not, there is a chance the implant will migrate back into the submammary pocket. To ensure permanent eradication of this potential space, it is useful to roughen the capsular surfaces (both on the retromammary surface and the anterior pectoral surface) and to use permanent sutures for the repair (Prolene, nylon, or Ethibond).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree