Management of Vasoconstriction

Paul K. Lim

Allen L. Van Beek

INTRODUCTION

Vas, from the Latin word for “vessel” or “container,” and spasmos, a Greek word meaning “convulsion,” combine to give the word vasospasm. Perhaps the more accurate word would be vasoconstriction because constrictus means “bound” or “drawn together”.1 Regardless of which term is used, the condition causes surgeons to perspire when the microsurgical tissue transfer fails to perfuse and creates painful suffering for patients with disease processes that have vasoconstriction as one of their hallmarks. This chapter discusses the management of vasoconstriction that often concerns plastic surgeons rather than the entire spectrum of diseases that have vasoconstriction as part of their presentation.

DEFINITIONS AND CLASSIFICATION

Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Maurice Raynaud, a French physician, first described the phenomenon of episodic acral pallor, cyanosis, and rubor in response to cold or emotional stress.2 The diagnosis of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP), also known as Raynaud’s disease, includes multiple attacks of RP occurring over at least 2 years without gangrene or tissue loss, and no known associated vaso-occlusive or systemic diseases. The episodes are typically symmetric and bilateral involving one or more digits.

Secondary RP is the diagnosis of these events but where there is a known causal or associated disease etiology. Tissue loss and asymmetric involvement are commonly seen in secondary RP.3

Iatrogenic Vascular Stenosis

This category of vascular spasm is not usually addressed under discussions of vasoconstriction diseases but is pertinent to surgeons performing microvascular surgery. Acute partial vessel occlusions confronting a surgeon are typically not from disease processes but have to do with small vessel or microvascular constriction associated with vessel manipulation. Vasoconstriction that occurs intraoperatively, postoperatively, or postvascular intervention and results in poor tissue perfusion falls into this category. When this occurs, there are many etiologies and suggested managements but the surgeon must be certain that the “constriction” is not actually a correctable surgical error.

PHYSIOLOGY

Acute Vessel Constriction

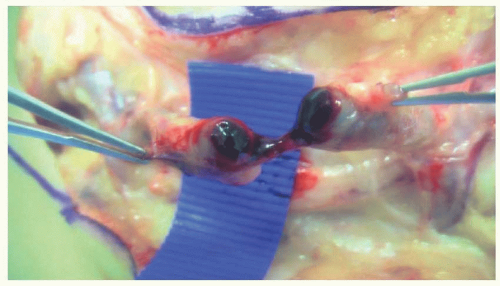

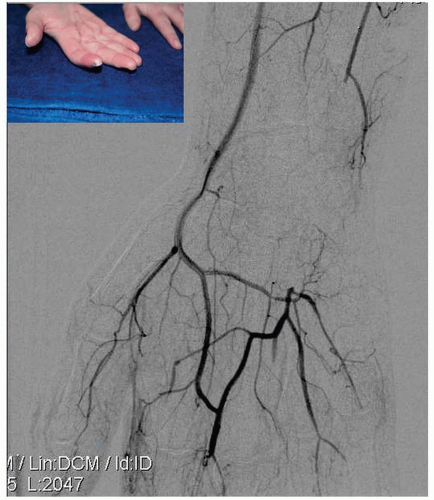

Large- and medium-sized vessels have pliable walls that increase and decrease their lumens in response to physiological and biochemical processes, but the largest impact on vascular resistance results from activity of small vessels and the capillary bed. Arteriovenous shunts are prominent in digits, hands, and feet. The shunts are regulated by vasoconstrictors, including norepinephrine, endothelin-1, vasopressin, angiotensin II, and transforming growth factor-β, and by vasodilators including prostacyclin, nitric oxide, and estrogen. These substances or mechanisms that influence the vessel walls are the basis for pharmacologic interventions.2 When the small vessels such as the digital arteries and their capillary outflow fields have their flow shunted, as occurs in RP, the resulting ischemia may produce some or all of the “five P’s” associated with arterial thrombosis: pallor, pain, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness, with the most common ones being pallor, pain, and loss of sensibility. Some vessel sclerotic processes, however, do not have an antecedent history of repeated episodes of vasospasm and present with an acute sequence of pallor, cyanosis, and rubor. Often the onset is abrupt, painful, and associated with an acute process that produces micro-emboli and even small vessel occlusion as seen with hypothenar hammer syndrome (Figures 87.1 and 87.2). Atrial fibrillation with associated mural thrombi, proximal large vessel stenosis with ulcerated plaques, and arterial aneurysms are the most common sources of emboli to distal vessels4 and are often responsible for acute onset vasospasm.

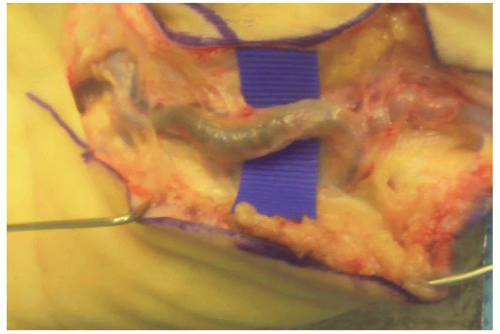

Chronic Vessel Occlusion

Vascular occlusion in proximal, larger vessels decreases the ability to respond to physiologic demands for more flow and increase the propensity for spasm to occur (Figure 87.3). Large vessel occlusions, if not recognized, may be the cause of unexpected acral vasoconstriction events. More often, distal occlusions are the reason for secondary RP to occur. Systemic sclerosis is associated with occlusion of small- and medium-sized vessels with severe fibrotic proliferation of the intima making episodic spasm events more severe as the disease progresses. Other rheumatologic diseases associated with secondary RP include systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and vasculitis.2

FIGURE 87.1. Aneurysm. (Hypothenar hammer syndrome.) Ulnar artery aneurysm producing acute onset of pain and vascular spasm to the ring and small fingers. |

DIAGNOSIS

Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon Versus Secondary Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Distinguishing between primary and secondary RP involves not only the clinical differences described above but also specific diagnostic criteria. Having any of the following rules out primary RP: 1. digital ulcerations; 2. elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate; 3. high titer of antinuclear antibody; and 4. abnormal capillaroscopic pattern. Capillaroscopy is typically performed by rheumatologists and involves the visualization of nailfold capillaries via dynamic fluorescence videomicros-copy and obtaining 50× to 1,000× magnification images with a digital video camera.5,6

Physiologic Assessment

Digital artery systolic blood pressure should be similar to the systolic blood pressure more proximally (segmental systolic pressures). A pressure drop at the digital level of more than 20 mm Hg compared with the brachial measurement is indicative of vascular disease.7 Blood flow in the finger can have wide variation, but flows less than 1 mL/min/100 mL tissue volume, pulp temperature lower than 30°C, and loss of ultrasound Doppler signals in the pulp of a digit are indicative of significant perfusion loss. Laser Doppler, ultrasound Doppler, finger cuffs, and temperature monitoring devices make clinical application of these parameters useful to surgeons.

Vascular Conduit Assessment

The gold standard for vascular assessment remains direct contrast angiography. Most importantly, it diagnoses or excludes proximal vascular disease or occlusion. However, in the presence of severe vasoconstriction, either present before or during angiography, the distal palm and digit vessels may not be well visualized. Improvement in magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) resolution has made distal vessel assessment possible even when vessel spasm is present and more importantly does not seem to contribute to or institute vessel spasm in those prone to attacks (Figure 87.4). Additionally, patients with profound spasm and tissue necrosis are often on anti-platelet therapy and, thus, at elevated risk for complications with direct angiography. One can start with the less invasive MRA and then proceed to direct angiogram if necessary.

TREATMENT

Management of Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon

The phenomenon, when it is a primary process, does not manifest the severity of sequelae noted with secondary RP. Medical intervention may be instituted in some patients, but surgery is rarely required. Noninvasive treatment, when needed, is the same as for secondary RP.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF RAYNAUD’S PHENOMENON

Secondary RP, by definition, has an etiology established. The most common etiologies are thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease), connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, vascular sclerosis, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), vibratory mechanisms, and hematologic syndromes. The prevalence of Buerger’s disease has decreased with decreased use of tobacco products. A high percentage of scleroderma patients have secondary RP. Hypothenar hammer syndrome may be more common than reported, and proximal etiologies such as TOS and ulcerated endothelial plaques provide some difficulty in establishing diagnoses. Treatment is directed at not only the ischemic manifestations but also the underlying disease process where possible.

Typically, plastic surgeons are consulted when there is impending tissue infarction, small acute ulcerations, gangrene, or chronic ulcers. The surgeon should be familiar with the medical treatment options to confirm that maximal medical management had been attempted before proceeding with surgical interventions. Additionally, the status of the vascular conduits proximally and distally is assessed

for diagnostic purposes as well as for potential operative planning.

for diagnostic purposes as well as for potential operative planning.

FIGURE 87.4. Vascular imaging. Example of the vascular detail in an MRA of the hand with digital occlusive disease from hypothenar hammer syndrome, with patient’s digital vessels on the radial side. |

Physical and Prevention Management

Eliminating cold exposure by using insulated containers, wearing gloves, and anticipating weather conditions may decrease the frequency of attacks. The entire body, not just the hands, should be covered, especially the forehead which is a known trigger site for attacks. Patients should avoid stimulants of vascular constriction such as caffeine, nicotine, ergots, ephedrine, amphetamines, decongestants, and β-blockers. Over-the-counter dietary, herbal, or medical products may contain these substances, so all products the patient takes are reviewed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree