Management of the Burned Hand

William C. Pederson

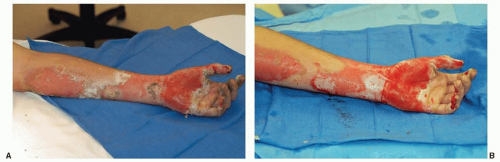

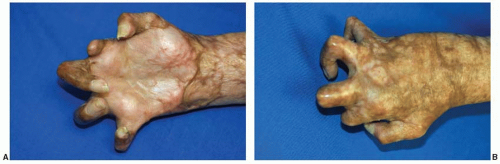

Burns of the hand remain problematic. Although more attention to the preservation of hand function has been directed to patients with severe burns, the hands are clearly less important than saving the patient’s life. This leads to initial neglect of the hands, and the resulting hand function is often poor. In addition, the hand may be difficult to reconstruct, since the damage involves not only the skin but also the tendons, joints, and bones. Once scar contracture has occurred, restoration of motion can be nearly impossible (Figure 88.1). Initial management is therefore paramount to allow later reconstruction of a functional hand.1 This chapter addresses early management, but concentrates on later reconstruction because this is where the plastic surgeon is most often involved (Chapter 16).

EARLY MANAGEMENT

The hands are frequently involved in thermal injuries, whether when accidentally grasping a hot object or protecting oneself from flames or steam coming from an automobile radiator (Chapter 15). The skin on the hands is relatively thick, and substantial heat is required to produce a full-thickness burn. Burns are generally classified by depth. First-degree burns are superficial and involve the epidermal layer. An example of this type of burn is sunburn, and these burns will heal spontaneously in a period of 2 to 3 days without scarring. Second-degree burns are intermediate in depth, involving the epidermis and a portion of the dermal layer. These types of burns are divided into superficial partial-thickness injuries and deep partial-thickness injuries. Superficial second-degree burns destroy the epidermis and the upper layer of the dermis, demonstrate blistering of the skin, and will heal spontaneously in 7 to 10 days with minimal scarring. Deep second-degree burns destroy the epidermis and a deeper layer of the dermis. These burns heal slowly and develop significant scars. Both types of second-degree burns are painful. Third-degree burns (or “full-thickness burns”) involve all layers of the epidermis and dermis and destroy all germinal elements of the skin. In these injuries, the skin looks like leather and is anesthetic. These third-degree burns will require some type of coverage because there is no capacity for the skin to re-epithelialize. Fourth-degree burns involve deeper structures, and these may even damage the bone. These types of burns are most common with electrical injuries.

FIGURE 88.1. Hand of patient with 60% total body surface area (TBSA) burn, managed in a burn unit. A. Palmar view. There is no motion in the fingers and poor sensibility. B. Dorsal view. |

Recognition of a first-degree burn is usually easy, but the difficulty comes in patients with deeper second-degree and third-degree burns. While proper management is predicated at least partially on an accurate evaluation of burn depth, this can be quite difficult in the early stages. Burns that will heal within 2 weeks should be allowed to do so in most instances, but deeper burns are generally best managed by early excision and grafting.2 Superficial second-degree burns generally are blistered. When the blisters are debrided, there is usually pink, moist dermal tissue underneath. Deeper second-degree burns will often have a more whitish and dry appearance (that of the deeper dermis) once blisters are debrided (Figure 88.2).

The initial management of hand burns involves gently cleaning the burns of foreign material and loose skin. I prefer to deflate intact blisters with an 18G needle allowing the epidermis to lie back down on the burn when possible. The status of tetanus immunization should be ascertained and the patient given a booster if immunizations are not up to date. Once the burns are cleaned, an attempt should be made to ascertain the depth of the injuries. Most second-degree burns should be allowed to heal, but deeper second-degree burns and third-degree injuries should be considered for early excision and grafting as noted above. With large burns this may not be possible, but with smaller burns in the hand, early excision of deeper burn injuries and grafting can lead to the best functional results.2 Once the burns are cleansed, they are covered with an antibiotic cream and a light dressing. Most outpatients receive silver sulfadiazine cream, but any type of antibiotic ointment (gentamicin or mupirocin) is probably adequate for smaller burns. Traditional wisdom has been to provide a short course of oral antibiotics as well, but there are no data to support this unless there is clinical evidence of infection. Hand burns should be splinted in a functional position, with the wrist extended, the metacarpophalangeal joints in flexion, and the interphalangeal joints in extension. Maintaining

motion of the hand and fingers is important, however, and thus the splint should be removed frequently and the fingers moved both actively and passively.3 I prefer to involve a physical therapist early on in the care of hand burns, as they can aid in daily wound care and also make sure that the fingers are kept mobile.

motion of the hand and fingers is important, however, and thus the splint should be removed frequently and the fingers moved both actively and passively.3 I prefer to involve a physical therapist early on in the care of hand burns, as they can aid in daily wound care and also make sure that the fingers are kept mobile.

Superficial burns to the hand should usually heal within 2 weeks, and the fingers must be kept moving during this period. One alternative to dressings is to cover the hand in antibiotic cream and place it in either a surgical glove or one of the various available gloves designed for the management of burns.4 This allows motion of the hand while keeping the burns moist and in contact with the antibiotic. This treatment is continued until the burn is healed. If the burns do not heal within 2 weeks, grafting will probably be necessary (Figure 88.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree