Mammary and Extramammary Paget’s Disease: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Mammary Paget’s disease (MPD) represents approximately 1% to 3% of breast neoplasms.1 The peak incidence is between 50 and 60 years of age and almost all reported cases occur in women.

Extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD) is a rare neoplasm that affects apocrine gland-bearing skin such as the vulva, perianal region, scrotum, and penis. The majority of patients are in the sixth through eighth decades of life.2–4 The genitals are the most commonly affected area, with EMPD representing 2% of all vulvar malignancies.3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

MPD is almost always associated with underlying in-situ or invasive intraductal adenocarcinoma of the breast (up to 98% of cases in some studies).5,6 Malignant cells directly extend from the underlying tumor into the epidermis via the lactiferous ducts. Rare cases are reported to have originated primarily in the epidermis of the nipple.7

Unlike MPD, in which almost all cases have a documented underlying neoplasm, EMPD does not have a consistent histogenesis. Primary EMPD occurs in the absence of underlying malignancy and accounts for the majority of patients with the disease. These cases represent a primary intraepithelial neoplasm of apocrine origin. The malignant cells are thought to originate from intraepidermal apocrine glands or from pluripotential cells of the epidermis. The neoplasm can then invade the dermis and metastasize via lymphatic spread. In contrast, cases of secondary EMPD are associated with an underlying apocrine carcinoma or internal malignancy. These cases are due to epidermotropic spread of malignant cells from the underlying tumor. Approximately 15% of cases are associated with an underlying internal carcinoma. The most common visceral malignancies associated with EMPD are carcinomas of the rectum, bladder, urethra, cervix, and prostate.4,8,9

Clinical Findings

Both MPD and EMPD present with a long-standing history of pruritic, erythematous, scaly, or velvety patches on the breast or in apocrine-rich areas such as the groin, perineum, or axilla. Given the rather nondescript appearance, there is frequently a significant delay in diagnosis as initial treatment often involves topical steroids and/or antifungal agents for presumed inflammatory or infectious dermatitis. After continued recalcitrance to therapy, a diagnostic biopsy is performed and the correct diagnosis is made.

MPD frequently presents as a unilateral, erythematous, scaly plaque involving the nipple and/or the areola (Fig. 121-1). Ulceration and weeping with an eczematous appearance is frequently present. Nipple erosion and discharge may occur. Retraction of the nipple can be seen. Pain, burning, and pruritus are frequently reported by patients. See Box 121-1 for differential diagnosis of MPD and EMPD.

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out | |

|---|---|---|---|

MPD | Nipple eczema Erosive adenomatosis Psoriasis Dermatophyte infection | Hailey–Hailey disease Pemphigus | Bowen disease Basal cell carcinoma Malignant melanoma |

EMPD | Candidiasis Tinea cruris Psoriasis Seborrheic dermatitis Nummular dermatitis | Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus Pemphigus Lichen simplex chronicus Lichen planus Drug eruption | Bowen disease Erythroplasia of Queyrat Malignant melanoma |

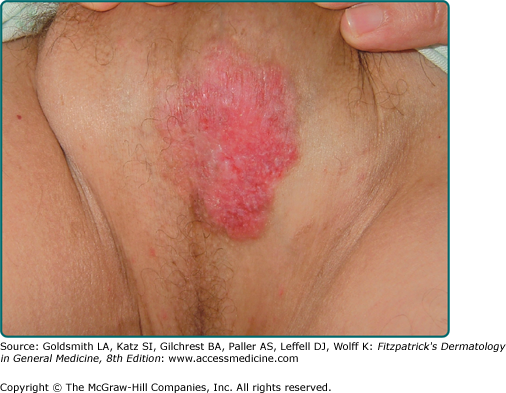

Lesions of EMPD are clinically similar to MPD and often present as a well-defined, moist, erythematous, scaly, eczematous plaque. Hypo- and hyperpigmentation can occur. Burning and intense pruritus are commonly reported. Lesions typically involve apocrine gland-bearing skin (i.e., genitoperineal region and axilla). The most frequent site is the vulva, but perineal, scrotal (Fig. 121-2), perianal (Fig. 121-3), and penile skin are also common areas. Rarely, ectopic EMPD has been reported in areas that are relatively free of apocrine glands, such as the chest, abdomen, thigh, eyelids, face, and external auditory canal.10–14 Given the less established association with underlying carcinoma in EMPD as compared to MPD, a palpable mass or other malignant stigmata are much less frequently found on physical examination.

Up to one-half of all patients with MPD have a palpable underlying breast mass.5,6,15,16 Of those patients with a palpable underlying tumor, half have axillary adenopathy due to lymph node metastasis.5,6 Palpable lymph nodes are less frequently present in EMPD. Complete physical examination including thorough full body skin exam is required in all cases of MPD and EMPD. Patients may present with symptoms and physical findings reflective of an underlying carcinoma or metastatic disease.

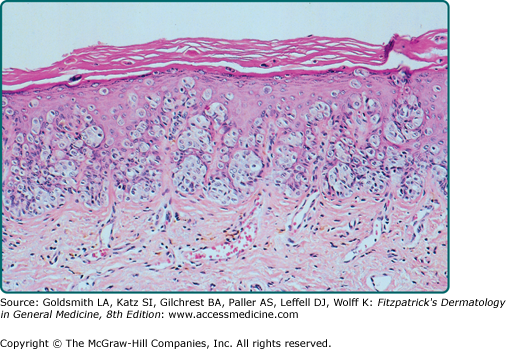

The intraepidermal adenocarcinoma of EMPD and MPD has a similar histologic appearance. There are groups, clusters, or single cells within the epidermis that show nuclear enlargement with atypia, prominent nucleoli, and well-defined ample cytoplasm (Fig. 121-4).15 Intercellular bridges are absent. The cells can be within all levels of the epidermis and can compress but preserve the basal layer without junctional nest formation. The cells can extend into the contiguous epithelium of hair follicles and sweat gland ducts. Acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis are often present. These cells have a “pagetoid” appearance and simulate other intraepidermal malignancies, such as melanoma, pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ, mycosis fungoides, cutaneous adnexal carcinomas (sebaceous carcinoma, porocarcinoma, and others), Merkel cell carcinoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and other epidermotropic cutaneous metastases. The cells of MPD and EMPD can be pigmented, which does not necessarily indicate they are melanocytic.

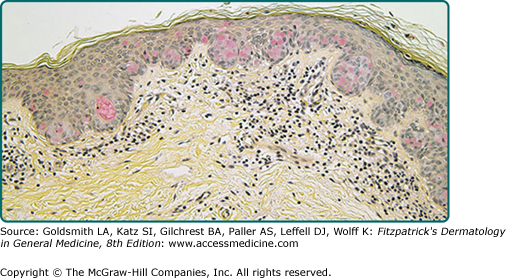

Paget’s cells have intracellular mucopolysaccharides, with EMPD having a greater amount of mucin as compared to MPD. As a result, cells frequently show positive staining for periodic acid-Schiff and diastase resistance, mucicarmine, Alcian blue at pH 2.5, and colloidal iron (see eFig. 121-4.1). However, there are can be focal “skip areas” that are devoid of mucin, resulting in sections of negative staining.

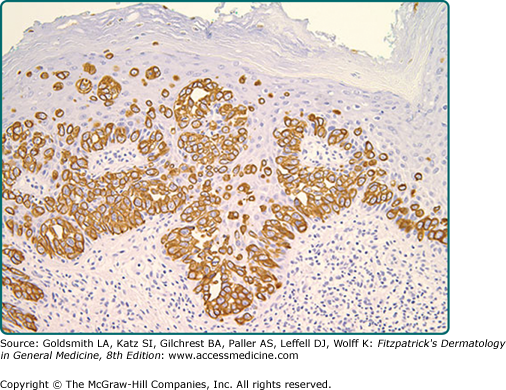

Immunohistochemistry is invaluable in making the correct diagnosis. Low-molecular-weight cytokeratin stains cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2) are sensitive markers for both MPD and EMPD (see eFig. 121-4.2). They are not completely specific, however, as both Toker and Merkel cells also exhibit CK7 positivity. The cells of MPD and EMPD may stain with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Ber-EP4, BRST-2, and HER-2/neu.17–19 The most useful keratin markers for Paget’s disease are CAM 5.2 and CK7, as they stain more than 90% of Paget’s cells but do not react with epidermal or mucosal keratinocytes.16,20 The cells of pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ typically do not stain with CK7 and CAM 5.2. S100, Melan-A (MART-1), and HMB-45 are useful markers to exclude melanoma, and are typically negative in MPD and EMPD. CK20 positivity has been found more frequently in cases of secondary EMPD with underlying carcinoma as compared to those cases of primary intraepithelial EMPD (CK7+/CK20−).21

Gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15) is a marker for apocrine epithelium and is typically positive in primary EMPD (not associated with underlying neoplasm). In contrast, GCDFP-15 is frequently negative in those cases of secondary EMPD with an associated malignancy.22

Mucin core protein (MUC) expression is useful in the diagnosis of MPD and EMPD.23 MUC1 positivity is noted in both MPD and EMPD. MUC2 expression is generally negative in primary EMPD, but may be expressed in those cases of secondary EMPD with an associated underlying gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma. MUC5AC is frequently positive in primary EMPD and less commonly noted in secondary EMPD or those cases of primary intraepithelial EMPD that becomes invasive. CDX2 is a regulatory gene involved in intestinal proliferation and has been suggested as a useful maker in EMPD associated with underlying colorectal tumors.19,24

Recent studies investigating the role of androgen receptor and 5α-reductase suggest an elevated 5α-reductase level in invasive (81%) compared with noninvasive (45%) cases of EMPD.25 For invasive cases, men had a significantly higher level of androgen receptor and 5α-reductase double positivity than women (70% vs. 17%), suggesting an autocrine synthesis of androgens in EMPD and gender-specific microenvironments that may contribute to invasiveness of the disease.

Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) has been shown to be significantly higher in patients with invasive lesions of EMPD as opposed to noninvasive cases.26

Complete workup of MPD and EMPD should include a thorough search for underlying malignancy. Mammography is required in all cases of MPD, with immediate biopsy of any detectable breast mass.

In cases of EMPD, workup is directed toward the possibility of an underlying gastrointestinal or genitourinary neoplasm. Imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, colonoscopy, barium enema, cystoscopy, intravenous pyelogram, chest X-ray and mammogram (for the rare association of EMPD and MPD), and blood work are appropriate tests. In two recent studies, patients with significantly elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) had a greater risk of death from the disease compared with patients with normal serum CEA, and the level of CEA paralleled disease course.4,8 Some reports have suggested that positron emission tomography (PET) scans may be useful for cases of invasive EMPD to evaluate for lymph node involvement and metastases.8,27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree