Malignant Atrophic Papulosis (Degos Disease): Introduction

|

In the early 1940s, Köhlmeier first described malignant atrophic papulosis, whereas Degos, Delort, and Tricot recognized it as a specific entity a year later.1–3 We now know that the clinically distinctive lesion of the so-called Degos disease is a marker of a cutaneous thrombo-obliterative vasculopathy rather than of a specific disease per se. Indeed, such lesions can be found in at least two distinctive clinical settings: (1) as an apparent idiopathic disease, either classic Degos disease or its benign variant, or (2) as a surrogate clinical finding in some connective tissue diseases such as the antiphospholipid syndrome, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and systemic sclerosis.

Epidemiology

Classic Degos disease is rare, with about 200 reported cases. It almost always occurs in Caucasians, but cases have been observed in African-American patients and in Japan. The disease most commonly presents between the third and fourth decades, but can occur at any age. Men are more often affected than women (ratio, 3:1). The majority of cases are sporadic, but familial cases have been described, and most of these cases are consistent with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.4

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of Degos disease is unknown. The histopathologic findings in patients with malignant atrophic papulosis suggest a primary vaso-occlusive process. Thus, a vascular coagulopathy and/or endothelial cell damage should be considered as the major pathogenic mechanism. A combination of prothrombotic factors possibly plays a role in triggering the full-blown disease. Extensive studies of prothrombotic factors were performed in some patients with Degos disease, and no single abnormality was repeatedly identified. All patients should be screened for the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies/lupus anticoagulant and cryoglobulins, although Assier et al did not find the former in their series of 15 patients.5 Inhibition of fibrinolysis and platelet abnormalities, including increased platelet adhesiveness and spontaneous aggregation, were reported in some patients.5–8

Clinical Findings

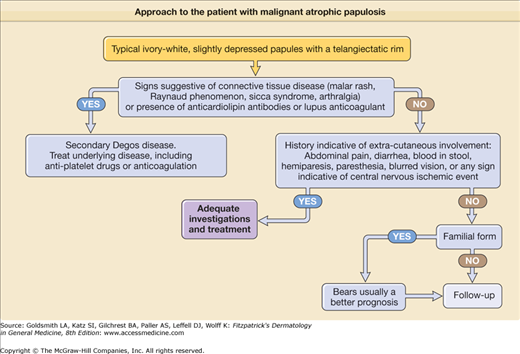

Patients seek medical advice for the appearance of small cutaneous lesions that usually are neither pruritic nor painful. In some patients, history and/or review of systems will reveal signs indicative of extracutaneous involvement: abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, nausea, blurred vision, hemiparesis, paresthesia, or any other sign indicative of an ischemic event. History can also give a clue to previous thromboembolic or obstetrical events suggestive of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

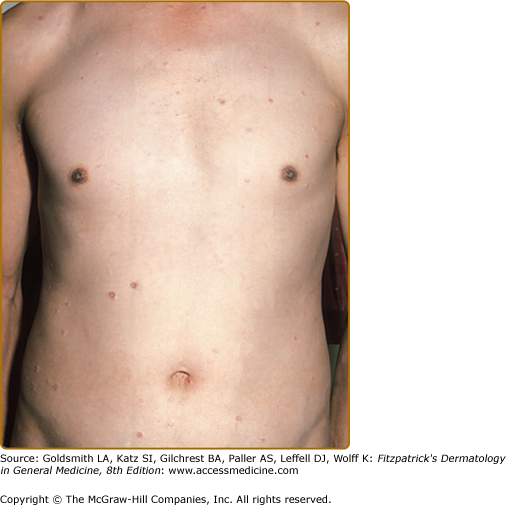

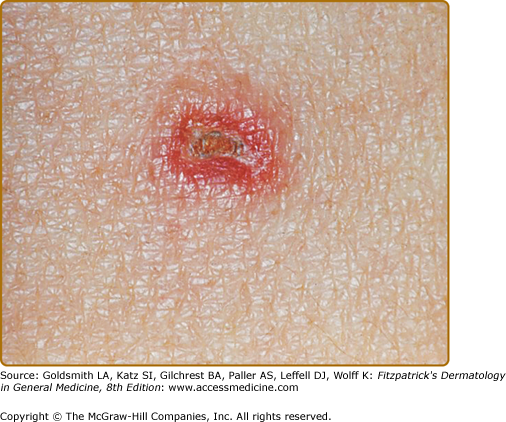

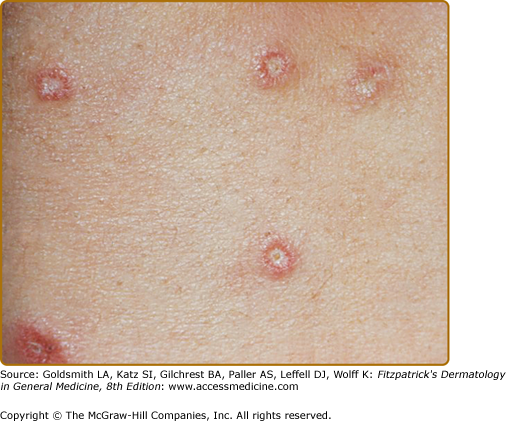

Cutaneous lesions start as crops of 2–10 mm, largely asymptomatic or mildly pruritic, fleshy or rose-colored macules that soon become round, smooth, often dome-shaped firm papules (Fig. 171-2). Some lesions display central umbilication and/or necrosis (Fig. 171-3). These lesions evolve over days or weeks to porcelain-white, atrophic papules with a rim of rosy erythema and/or telangiectases (Fig. 171-4). A fully developed lesion therefore closely resembles lesions of atrophie blanche. In time, the reddish border disappears, and only a varicelliform white scar remains. Usually, the lesions are separated from each other, but they may coalesce, leading to polycyclic atrophic areas or to skin ulcerations.

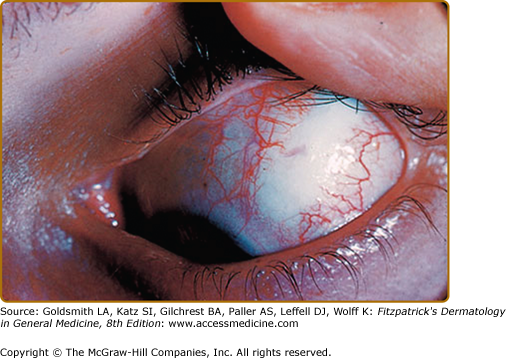

The lesions are localized on the trunk and limbs. Palms, soles, face, scalp, and genitalia are usually spared, although there are exceptions. Exclusive acral localization is suggestive of connective tissue disease. A linear distribution was reported.9 Eye involvement is possible, and the most common manifestation is an avascular patch on conjunctivae, but sclerae, episclera, retina, choroids, and optic nerves may be affected (see eFig. 171-4.1).

In classic Degos disease, the number of cutaneous lesions varies from a few to more than one hundred. Cutaneous findings usually precede the systemic manifestations that may involve the gastrointestinal tract, with bowel perforation and peritonitis, and/or the central nervous system, with hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke. Rarely, cutaneous lesions occur simultaneously or after gastrointestinal or central nervous system involvement. Postmortem studies have revealed small vessel thrombotic involvement of many organs, including kidney, bladder, prostate, liver, pleura, pericardium, lung, and eyes.10 Some patients with classic Degos disease have antiphospholipid antibodies, and this raises the possibility of a relationship with a primary antiphospholipid syndrome.

A benign form of Degos is now widely recognized. In this form, only skin involvement is found, and most of the familial cases are benign.4 Development during pregnancy has been reported in a patient with antiphospholipid antibodies,11 as well as a case occurring in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.12 A patient developing Degos disease after interferon injections, a drug known to induce atrophie blanche-like lesions13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree