Lymphogranuloma Venereum: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease due to specific Chlamydia variants that is rare in developed countries. It is endemic in East and West Africa, India, Southeast Asia, South and Central America, and some Caribbean Islands; and accounts for 7%–19% of genital ulcer diseases in areas of Africa and India.1,2 The peak incidence occurs in persons 15–40 years of age, in urban areas, and in individuals of lower socioeconomic status. Men are six times more likely than women to manifest clinical infection.3 The incidence of LGV is low in the developed world where cases are usually limited to travelers or military personnel returning from endemic areas. Since 2003, however, outbreaks of LGV have appeared in Europe, Australia, and North America, particularly in the form of proctitis, among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive men who have sex with men (MSM).4–11

LGV is contracted by direct contact with infectious secretions, usually through any type of unprotected intercourse, whether oral, vaginal, or anal. Transmission efficiency is unknown.12,13 Sexual practices such as fisting and sex-toy sharing may be other routes of transmission.4 In a recent study that compared sexual behaviors in men with LGV and men with non-LGV chlamydial proctitis, fisting was a major predisposing factor.14 An epidemic of LGV has been reported among “crack” cocaine users in the Bahamas.15

Due to underdiagnosis and underreporting, the epidemiology of LGV remains poorly understood. Common diagnostic laboratory methods are nonspecific and not readily available in endemic areas. Even in industrialized countries, only a few laboratories offer specific assays to LGV serovars. Without such assays, many LGV cases are misdiagnosed as common chlamydial urogenital infection. Underdiagnosis of LGV is also largely due to the presence of an asymptomatic carrier state. Women, in particular, may harbor asymptomatic persistent infection in the cervical epithelium, thus serving as reservoirs of the infection as they do for other urogenital chlamydial infections and gonorrhea. Recently, a large study conducted in the United Kingdom found that only 6% of MSM were asymptomatic carriers of LGV Chlamydia serovars; the majority of cases of LGV in the rectum and urethra were symptomatic.16 Infectivity in men usually ceases after healing of the primary mucosal lesion. Interestingly, most of the detected cases in the recent outbreaks are in men who practice receptive anal sex, suggesting that a high proportion of men who practice insertive anal sex are mis- or undiagnosed. The reasons behind this are unclear but may be organism-related, host-related (sexual practices such as fisting and the use of sex toys, intravenous drug use, HIV status, etc.) or physician-related (failure to diagnose genital LGV). The resurgence of LGV as a health problem may simply reflect increased awareness rather than increased incidence.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

LGV (tropical or climatic bubo, lymphopathia venerea, Nicolas–Favre disease) is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serovars (serologic variants) L1, L2, and L3.17 Most of the recent outbreaks are caused by a number of strains of C. trachomatis L2 serovar (L2b), suggesting that these outbreaks most likely represent increased awareness of a slowly evolving endemic.7–9,16,18,19

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria characterized by two distinct morphologic forms: (1) the small metabolically inactive and infectious elementary body, and (2) the larger metabolically active and noninfectious reticulate body. (eFig. 203-0.1). C. trachomatis has been subdivided into several serovars that differ in their major outer membrane proteins, and which are associated with several diseases. Serovars A, B, and C are the causes of trachoma ocular infections, whereas serovars D-K are responsible for ocular, genital and respiratory infections.20 In contrast to the A-K serovars that remain confined to the mucosa, LGV serovars are more invasive and have a high affinity for macrophages.17 After being inoculated onto the mucosal surface, the organisms replicate within macrophages, and find their way to the draining lymph nodes (LNs), and cause lymphadenitis.

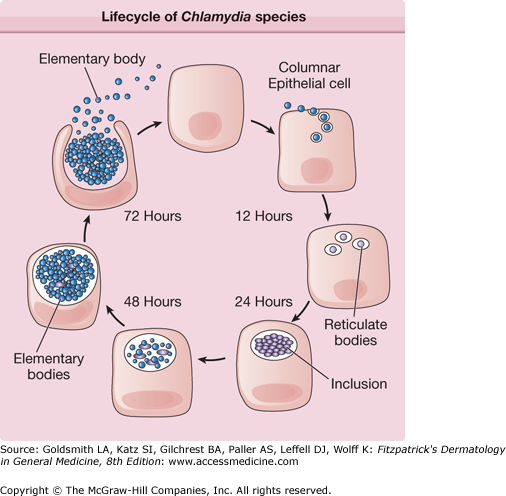

eFigure 203-0.1

Lifecycle of Chlamydiae species, which involves two forms of the organism: the elementary body (EB), which is the nonreplicating extracellular infective form, and the reticulate body (RB), which is the intracellular replicative form. The life cycle begins when an EB is endocytosed into a host epithelial cell. Once inside the host cell, the EB transforms into a RB, which in turn undergoes binary fission within vacuoles called inclusions. The RBs then reorganize into EBs. After 48–72 hours, the EBs are released from the host cell to infect adjacent cells or to infect another person.

Clinical Findings

Clinical manifestations are protean, depending on the sex of the patient, acquisition mode, and the disease stage. Three clinical stages characterize LGV. Nonspecific cutaneous lesions such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, urticaria, and scarlatiniform exanthema may occur with any of these stages.21

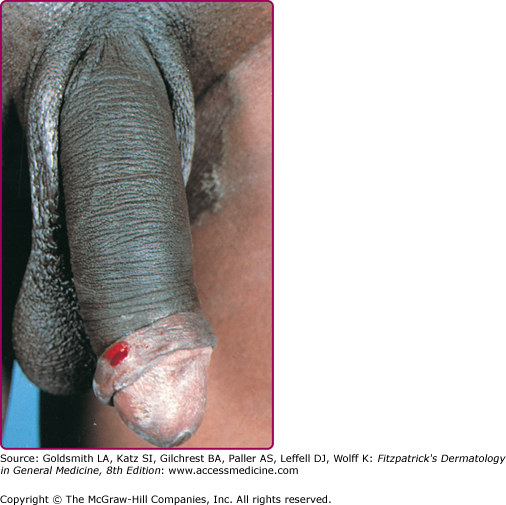

Three to 30 days after infection, 5- to 8-mm painless erythematous papule(s) or small herpetiform ulcers appear at the site of inoculation (Fig. 203-1). Painful ulcerations22 and nonspecific urethritis23 are less common. In males, the lesion is usually found on the coronal sulcus, prepuce, or glans penis; and in females on the posterior wall of the vagina, vulva, or, occasionally, the cervix. Inoculation may also be rectal or pharyngeal. The primary lesion is transient, often heals within a few days, and may go unnoticed.

A few weeks after the primary lesion appears, marked LN involvement and hematogenous dissemination occur, manifested by variable signs and symptoms, including fever, myalgia, decreased appetite, and vomiting. Photosensitivity may develop in up to 35% of the cases, often 1–2 months after bubo formation.24 Less commonly, patients may develop meningoencephalitis, hepatosplenomegaly, arthralgia, and iritis.25,26 The lymphadenitis episodes often resolve spontaneously in 8–12 weeks. Depending on the mode of transmission, two major syndromes are distinguished.

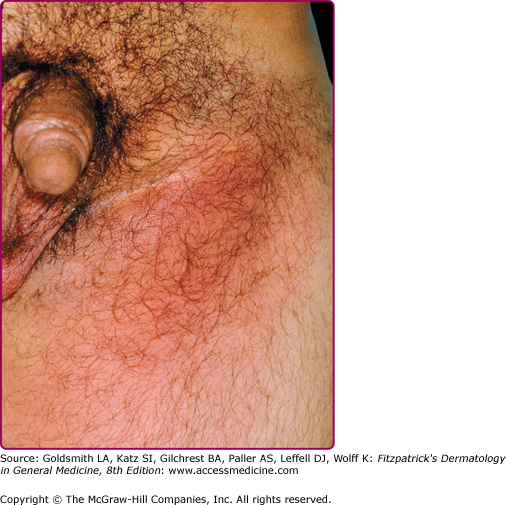

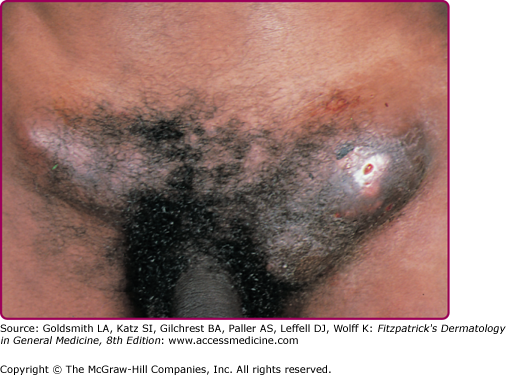

The acute genital syndrome (GS) or inguinal syndrome is characterized by inguinal and/or femoral LN involvement and is the major presentation in men. Initially, the skin overlying the affected LN is erythematous and indurated. Over the subsequent 1–2 weeks, the LN enlarge and coalesce to form a firm and tender immovable mass (bubo) (Fig. 203-2), which may rupture and drain through the skin, forming sinus tracts. Bilateral involvement occurs in one-third of the cases (Fig. 203-3). Nodal enlargement on either side of the inguinal ligament, the “groove sign,” is pathognomonic of LGV, but only presents in 10%–20% of cases27 and is rarely bilateral.28 In women, inguinal lymphadenitis is unusual because the lymphatic drainage of the vagina and cervix is to the deep pelvic/retroperitoneal LN. When these nodes are involved, low abdominal/back pain that exacerbates upon lying supine and pelvic adhesions may ensue.

The acute anorectal syndrome (ArS) is characterized by perirectal nodal involvement, acute hemorrhagic proctitis, and pronounced systemic symptoms. It is the most common presentation in women and in homosexual men who practice anal sex. The major source of rectal spread in women is the internal lymphatic drainage of the lower two-thirds of the vagina. Patients may complain of anal pruritus, bloody rectal discharge, tenesmus, diarrhea, constipation, and lower abdominal pain.5,29 In a recent study, 96% of MSM patients presented with signs and symptoms of proctitis.30 Despite affecting mostly HIV-positive MSM, LGV has not behaved as an opportunistic infection in the recent outbreak, and clinical features have not differed between HIV-positive and HIV-negative cases.31

This stage is more seen in women with untreated ArS, and includes rectal strictures (most common) and abscesses, perineal sinuses, rectovaginal fistulae (leading to “watering can perineum”), and “lymphorrhoids” (perianal outgrowths of lymphatic tissue). Esthiomene (Greek, “eating away”) is a rare primary infection of the external genitalia (mostly in women), leading to progressive lymphangitis and genital destruction. Infertility and “frozen pelvis” are potential sequelae of ruptured deep pelvic nodes in women. Late sequelae of the GS are less common and include urethral strictures and genital elephantiasis with ulcers and fistulas (in 4% of cases).32 Penile deformities such as the saxophone penis may also occur.33

Extragenito-anal inoculation of LGV is rare. Oropharyngeal infection may manifest initially as pinhead-sized vesicles on the lip, and later on as cervical lymphadenopathy with constitutional symptoms, closely mimicking lymphoma. Tonsillitis, supraclavicular and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and pericarditis rarely occur.34–38 Ocular autoinoculation of infected discharges may lead to conjunctivitis with marginal corneal perforation, often with preauricular lymphadenopathy.39 Inhalation of LGV serovars L1 and L2 may accidentally occur in laboratory workers and lead to pneumonitis with mediastinal and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy.40

Laboratory Tests

Diagnosis of LGV may be difficult, but LGV should be suspected in any patient with infected sexual contacts, genital ulcer, perianal fistula, or bubo. The accuracy of clinical diagnosis has been reported to be as low as 20%.41 Therefore, laboratory tests are important to establish the diagnosis and are usually divided into two broad categories: (1) nonspecific tests that do not distinguish between LGV and (2) non-LGV serovars, and specific LGV tests. In practice, a positive test on LN aspirate is considered diagnostic of LGV, in contrast to a positive test on primary genital lesion where further specific testing is required to rule out common chlamydial urogenital infections.