27 Lower bodylifts

Synopsis

The subcutaneous abdominal fat is divided into a superficial and deep layer by the superficial fascial system, which in the abdomen is called Scarpa’s fascia.

The subcutaneous abdominal fat is divided into a superficial and deep layer by the superficial fascial system, which in the abdomen is called Scarpa’s fascia.

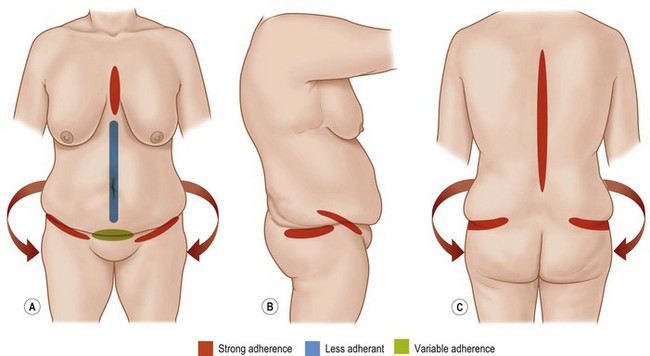

The skin/fat envelope is tethered to the underlying musculoskeletal anatomy in zones of adherence. These include the spine, the sternum, the linea alba of the abdomen, the inguinal area, the suprapubic area and the area between the hip and lateral thigh fat.

The skin/fat envelope is tethered to the underlying musculoskeletal anatomy in zones of adherence. These include the spine, the sternum, the linea alba of the abdomen, the inguinal area, the suprapubic area and the area between the hip and lateral thigh fat.

Massive weight loss (MWL) patients make up the majority of patients who undergo lower bodylift/belt lipectomy surgery. Second are females with a BMI in the range of 26–28. Third are normal weight females who wish a more dramatic improvement than an abdominoplasty alone.

Massive weight loss (MWL) patients make up the majority of patients who undergo lower bodylift/belt lipectomy surgery. Second are females with a BMI in the range of 26–28. Third are normal weight females who wish a more dramatic improvement than an abdominoplasty alone.

Three factors affect patient presentation: the BMI, the fat deposition pattern, and the quality of the skin/fat envelope.

Three factors affect patient presentation: the BMI, the fat deposition pattern, and the quality of the skin/fat envelope.

Bodylift/belt lipectomy procedures can be thought of as a circumferential wedge excision of the lower trunk. One end of the spectrum of procedures is the lower bodylift type II (Lockwood technique) and the other end is the belt lipectomy/central bodylift (Aly and Cram technique).

Bodylift/belt lipectomy procedures can be thought of as a circumferential wedge excision of the lower trunk. One end of the spectrum of procedures is the lower bodylift type II (Lockwood technique) and the other end is the belt lipectomy/central bodylift (Aly and Cram technique).

Patients presenting for this surgery require a complete medical assessment and a thorough physical examination.

Patients presenting for this surgery require a complete medical assessment and a thorough physical examination.

In planning a bodylift/belt lipectomy, scar position can be approximated by simulating the tissue dynamics at the time of closure. Anteriorly, the inferior marks control scar position and posteriorly, the superior marks control the scar position.

In planning a bodylift/belt lipectomy, scar position can be approximated by simulating the tissue dynamics at the time of closure. Anteriorly, the inferior marks control scar position and posteriorly, the superior marks control the scar position.

The operative sequence usually involves anterior surgery first, followed by posterior surgery and closure.

The operative sequence usually involves anterior surgery first, followed by posterior surgery and closure.

Postoperative care requires hospital level nursing with attention to patient positioning, early ambulation, fluid infusion and pain control.

Postoperative care requires hospital level nursing with attention to patient positioning, early ambulation, fluid infusion and pain control.

Major complications are possible, but the commonest problem is seroma.

Major complications are possible, but the commonest problem is seroma.

Basic science and disease process

Anatomy

It is important to have a clear understanding of the blood supply of the abdomen, when contemplating circumferential dermatolipectomy of the lower trunk. The anatomy of abdominal wall blood supply is thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 25.

There are areas within the trunk where the skin/fat envelope is tethered to the underlying musculoskeletal anatomy, restricting either descent or elevation, which can occur with aging, weight fluctuation, or surgical manipulation. These areas are called “zones of adherence” and act like “hooks” for the skin/fat envelope to hang on to as it falls down, especially after the skin has been stretched by excess weight and then deflated by weight loss. It is important to understand where these zones of adherence are located and how they affect tissue draping (Fig. 27.1). The zones of adherence overlying the spine and the sternum are both strong areas of adherence and are always present, while the zone of adherence overlying the midline linea alba of the abdomen is often week to non-existent. There are strong zones of adherence overlying the inguinal region bilaterally that play an important role in controlling final scar position during bodylift/belt lipectomy. A more variable zone of adherence is located in the horizontal suprapubic area which when present leads to a suprapubic crease. Its strength and attachment is quite variable from individual to individual. This zone of adherence, along with the inguinal zones of adherence, is responsible for a panniculus hanging over the mons pubis.

Another important zone of adherence is located between the hip and lateral thigh fat deposits. This is an important attachment because it acts like a stop gap of the lateral thighs preventing movement of tissues, either in the superior or inferior direction, especially during manipulations at surgery. In some procedures, such a “lower bodylift type II”, as described by Lockwood,1,2 this zone of adherence is intentionally destroyed to allow for significant elevation of the lateral thighs.

The disease process

There are three groups that can potentially benefit from bodylift/belt lipectomy.3 Although all of these groups will share some of the same indications and principles in design of the operations, they differ and should be considered here.

Massive weight loss patients

Issues specific to this patient group are reviewed in . Massive weight loss (MWL) patients make up the majority of patients who undergo bodylift/belt lipectomy.3 The lower trunk of MWL patients can be thought of as a balloon. As patients gain weight and then lose it, the balloon is initially stretched by the weight gain then deflated as weight loss ensues. Like a balloon that has been inflated for a long time, the intrinsic elasticity of the skin is irreversibly altered during this process, leading to redundant lax skin, which is almost always circumferential in nature. The usual pattern is of an inverted cone (Fig. 27.2).

The 20–30 pounds overweight group

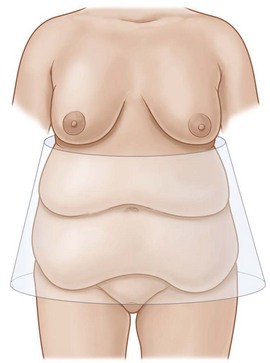

These patients present with lipodystrophy of the lower trunk that is circumferential in nature which leads to generalized lack of definition of the lower trunk (Fig. 27.3).

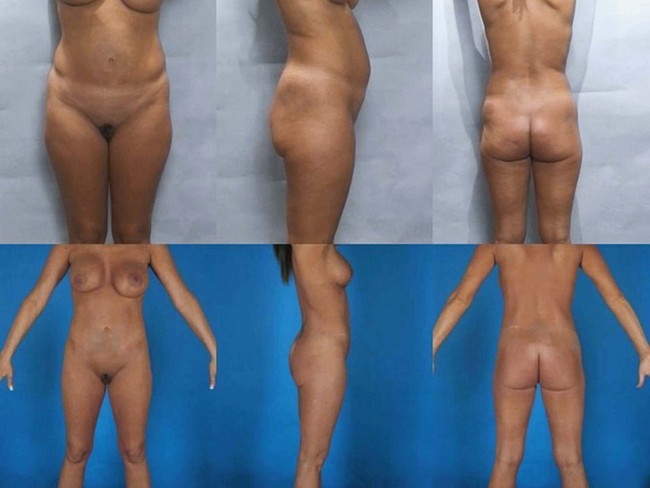

Normal weight patients group

A third group that may benefit from bodylift/belt lipectomy are normal weight patients who ordinarily would be considered candidates for an abdominoplasty, but desire more dramatic improvements in lower truncal contour. These patients often desire a remarkable improvement in their anterior thighs, lateral thighs, buttocks and lower back. In many similar patients, liposuction can improve all of these areas when combined with an abdominoplasty, however, if patients desire significant lifting and contour delineation, then a circumferential excisional procedure is required (Fig. 27.4).

A subgroup of normal weight patients that can benefit from a bodylift/belt lipectomy is made up of older patients whose skin will not contract with liposuction due to skin laxity and will require the pull created by the circumferential excision (Fig. 27.5).

Diagnosis and patient presentation

Most of the subsequent discussions will be centered around the MWL patients and the other groups will be mentioned when appropriate. Although MWL patients are grouped together they are quite variable in their presentation (Fig. 27.6). Three factors seem to affect the presentation; the BMI at presentation, the fat deposition pattern and the quality of the skin/fat envelope.

BMI level at presentation

Massive weight loss patients will present to the plastic surgeons at different BMI levels. For some, this level is still very high, BMIs of ≥35; for others it may be intermediate, BMIs of 30–35; and for others, the BMI may drop to the mid or low 20s (Fig. 27.6). If the patient loses weight through bariatric surgery, then the type of bariatric operation utilized is likely to affect their final BMI. Lap-band patients tend to lose the least weight, while gastric bypass patients tend to lose more weight, and gastric sleeve patients loose an intermediate amount. Duodenal switch patients are uncommon, but tend to experience the largest drops in BMI.

Fat deposition pattern

The type of deformity that a MWL patient presents with also depends on their particular fat deposition pattern. Humans are born with a genetically controlled pattern of fat deposition, as well as a fat loss pattern. For example, females tend to store fat in the extraperitoneal space, the lower abdomen, hips and thighs; a pattern often referred to as “pear-shaped” (Fig. 27.7). Males on the other hand tend to store fat more centrally in what is often referred to as “apple-shaped”, where fat is deposited intraperitoneally and in the flanks (or “love handles”), and less fat is deposited in the thighs (Fig. 27.7). The “pear’ and “apple” patterns are only a couple of the many potential fat deposition patterns present in the population.

The skin/fat envelope

The skin/fat envelope is what a plastic surgeon operates on and its intrinsic properties are especially important. Some patients present with very pliable and thin skin/fat envelopes, while others will present with very thick nonpliable tissues. A concept that the authors have found very helpful in examining these patients is the “translation of pull” (Fig. 27.8). For example, when examining the patient prior to surgery the lateral abdominal tissues are pinched simulating the effects of the lateral abdominal resection of a bodylift/belt lipectomy on the distal thigh, which can be predictive of the final result with a certain degree of accuracy. Conversely, if the pinch demonstrates very little translation of pull to these areas, as in the case of patients who present with high BMIs and thick, nonpliable, skin/fat envelopes, this also can be used to predict the final result. As a general rule, the greater the BMI drop, the more translation of pull will be present. Thus, a patient who drops from a BMI of 60–30 will demonstrate a greater translation of pull than a patient who drops from 35 to 30.

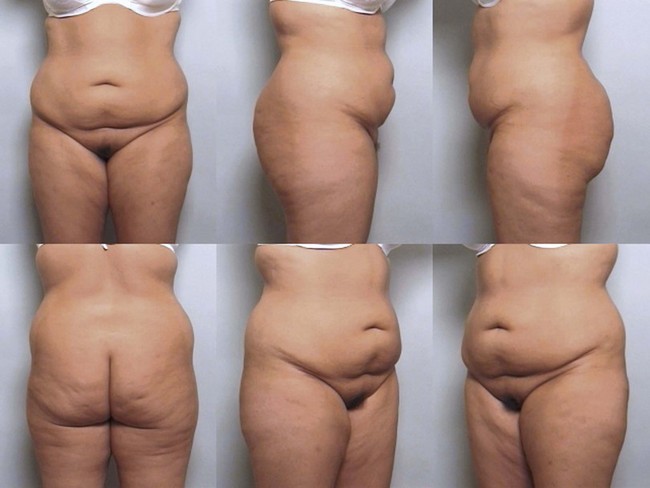

Commonalities of presentation

Almost all massive weight loss patients present with a “hanging panniculus”. The size and shape of the panniculus will vary from one patient to the other based on their intrinsic fat deposition pattern (Fig. 27.9). Almost every massive weight loss patient will present with a “ptotic mons pubis”. The most obvious deformity is vertical excess with varying degrees of horizontal excess.

Fig. 27.9 Six MWL patients demonstrating the variety in shape and size of their presenting panniculi.

As with the thighs, the buttocks in the massive weight loss patient are usually ptotic due to the effects of the weight gain/loss process. Those that present with a high BMI, above 35, will most often present with overly projected buttocks. Patients that stabilize at a low BMI of ≤26, will often present with fairly flat underprojected buttocks. Many massive weight loss patients also present with a lack of demarcation between the lower back and buttocks (Fig. 27.10).

Many patients present with back rolls that are bothersome. Some back rolls are located in the lower back and those are generally amenable to improvement through bodylift/belt lipectomy. Superior back rolls, usually contiguous with breast rolls, or just below them, are not affected by bodylift/belt lipectomy procedures and must be addressed through upper bodylift procedures (Fig. 27.11). A small subset of patients will present with “intermediate back rolls” which are located in what the authors call “no man’s land” between the upper and lower back rolls. These are very difficult to treat because they may not be eliminated by a bodylift/belt lipectomy or an upper bodylift. Fortunately, these are rare presentations.

Patient selection

Although a “bodylift/belt lipectomy” can be thought of as a circumferential wedge excision of the lower trunk there are variations of the procedure.4 We have categorized what we feel to be the ends of the spectrum of bodylifts and will go over the differences so that the reader may understand what each can accomplish. On one end is the “lower bodylift type II”, as originally described by Lockwood.1,2 On the other end, there is the “belt lipectomy” as described by the authors, originally in Iowa.3 It is not the intent of the authors to suggest that one type of bodylift should be utilized over the other. Rather it is hoped that the surgeon would be familiar with these techniques and be able to individualize the particular procedure to the needs of their particular patient.

Lower bodylift type II (Lockwood technique)

In this type of bodylift, the overall circumferential wedge of resection is located lower onto the lower trunk. The procedure can be thought of as a truncal-thigh lift, not just a truncal lift.5 The bilateral zones of adherence located between the hip and trochanteric fat deposits are intentionally destroyed to allow the surgeon to lift the lateral and anterior thighs very aggressively. This is made easier by extensive circumferential liposuction of the soft tissue envelope of the thighs. These steps discontinuously undermine the thighs from the underlying musculoskeletal system allowing for a vigorous elevation of the entire thigh complex, with the exception of the posterior thigh. The posterior thigh can not be lifted directly because of the infra-buttocks zone of adherence which prevents such elevation.

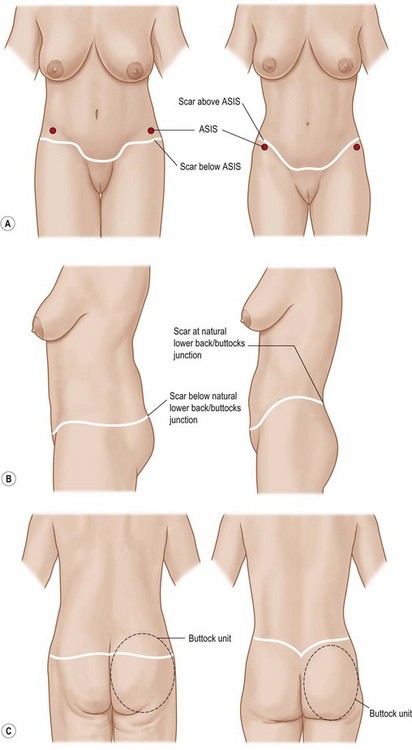

The results of a lower bodylift type II are impressive in its elevation of the thighs. Since the circumferential wedge of excision is low, it creates a fairly low scar that can be covered by most underwear or swimwear patterns (Fig. 27.12). There are disadvantages and limitations of lower bodylift type II. Since the final scar is intentionally created below the widest aspect of the pelvic rim, the waist is not narrowed as much as it would if the final scar is created above. The authors call this the “sundress effect” because it brings the upper truncal tissues across the widest aspect leading to blunting of the waist, rather than narrowing. Anteriorly, the scar is considerably lower than the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), which poses no significant problem if the abdominal flap that is brought down to the level of the scar is thin. However, if the abdominal flap is thick, as in higher BMI patients, it will add to the prominence of the ASIS region, which should be flat, not convex. A disadvantage of a posterior low scar in a lower bodylift type II, which runs across in the midst of the upper third of the buttocks unit, violates the unit principle. This is not problematic in patients who value hiding the scar within low underwear lines and do not require demarcation between the lower back and buttocks, i.e., a male patient. On the other hand, most female patients desire as much buttocks definition as possible and demarcation between the lower back and buttocks (see Box 27.1 for the main advantages and disadvantages of the lower bodylift type II).

Belt lipectomy/central bodylift

Belt lipectomy/central bodylift procedures overall have a more superiorly based wedge of excision when compared with a lower bodylift type II.6 There is some weakening of the zone of adherence between the hip and lateral thighs but no attempt is made to completely destroy them, as in a lower bodylift type II. These differences lead to a more superiorly positioned scar, circumferentially around the lower trunk. Posteriorly, the scar is ideally positioned at the natural junction between the lower back and buttocks, which promotes more attractive buttocks, demarcates the lower back from the buttocks, and in most patients creates a narrower waist. Anteriorly, the scar positioning above the ASIS further promotes narrowing of the waist by “cinching” above the widest aspect of the pelvic rim. This is especially helpful in patients who present with thick abdominal flaps, which will fit in a depression above the ASIS, rather than over it. Because the zones of adherence are only weakened during this technique, the thighs are not as aggressively lifted as in a lower bodylift type II.

It is important to note that a plastic surgeon who treats MWL patients on a regular basis should be familiar with both the lower bodylift type II and belt lipectomy/central bodylift, so that they may mix and match these techniques to create the best possible outcome for a particular patient (see Box 27.2 for the main advantages and disadvantages of belt lipectomy/central bodylift).

Selection criteria

The BMI at presentation should be a very important factor in determining whether a plastic surgeon should operate. As will be discussed later in this chapter, complications increase with increasing BMIs.7 Many plastic surgeons do not operate on patients that present with a BMI >32. This is a reasonable level, especially for those surgeons who are new to MWL body contouring surgery and/or circumferential procedures. The authors of this chapter routinely operate on patients in higher BMI ranges but they accept a much higher complication rate, especially if the BMI is >35, where the complication rate is around 100%.

If a patient presents with too much intra-abdominal content to allow flattening of abdominal contour by muscle wall plication, then the result of a circumferential procedure is very similar to that attainable by panniculectomy.8 It would thus be prudent to avoid the increased risk of the circumferential excision and limit the procedure to a panniculectomy.

The recovery period after a circumferential dermatolipectomy can be quite challenging both physically and psychologically. Choosing a patient with unstable psychological problems to go through the prolonged and arduous recovery can result in disastrous consequences. (Criteria for patient selection are given in Box. 27.3.)