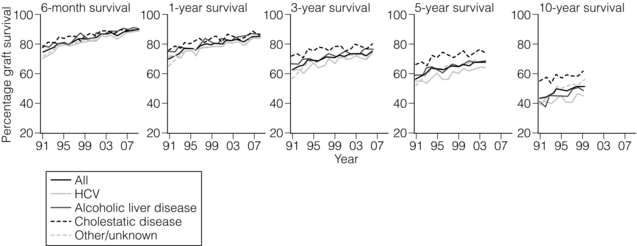

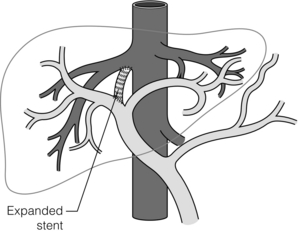

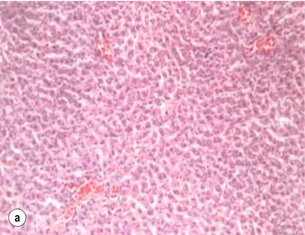

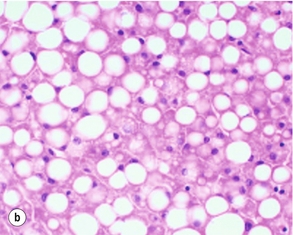

8 Liver transplantation has evolved over the past six decades from a risky procedure with poor outcome to the standard of care for the patient with end-stage liver disease. From the initial attempts of Dr Thomas Starzl in the USA and Sir Roy Calne in the UK, liver transplantation has progressed from a procedure that was experimental, performed on moribund patients with irreversible chronic liver disease with an occasional long-term survival, to a procedure in many centres with 1-year survival exceeding 90% (Fig. 8.1).1–3 Consistent improvements in surgical technique, immunosuppressive regimens and postoperative care, paired with better selection and management of pre-transplant patients, has resulted in an increased number of recipients able to benefit from transplantation. Ironically, these developments combined with the static and/or decreasing number of potential donors in many countries have led to increased waiting-list mortality. In the USA, waiting-list mortality can exceed 20% in many regions and highlights the problem of organ shortage. Although liver transplantation has proven to be a great success in its relatively short history, it should not be considered as either the initial or primary treatment modality for most liver diseases. In this era of organ shortages, it is important to understand the indications and contraindications for liver transplantation, current and future changes in the organ allocation system, and methods for increasing the donor pool, such as split or live donor grafts and using organs from extended criteria and non-heart-beating donors. Figure 8.1 OPTN data shows 6-month to 10-year survival following liver transplantation for various indications. Recipients transplanted for cholestatic liver diseases (PBC, PSC) enjoy improved long-term survival. At the time of writing, there are nearly 17 000 patients waiting for a liver transplant in the USA. Prior to listing, all patients undergo extensive medical and psychosocial evaluation. Most programmes have adopted a multidisciplinary approach for evaluating potential liver transplant recipients that usually includes representatives from hepatology, surgery, anaesthesia, infectious disease, psychiatry, social work, transplant nursing and finance/insurance. Input from consulting services such as cardiology, pulmonology, neurology, nephrology, etc. is obtained as needed. After all testing and consultations have been obtained, each patient is presented to the multidisciplinary committee and voted on to accept, reject or defer until all information is available, such as an outstanding screening test. In the USA, accepted patients are listed with the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and prioritised by their Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score.4,5 A comprehensive list of the currently accepted indications for liver transplantation is shown in Box 8.1. A brief review of the MELD score is needed since it has become the main tool used for liver allocation in the USA and in some countries around the world. Initially developed at the Mayo Clinic, the MELD score uses the patient’s values for serum bilirubin, serum creatinine and the international normalised ratio for prothrombin time (INR) to predict survival.6 It is calculated according to the following formula: The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/ UNOS) has made the following modifications to the score:7 • If the patient has been dialysed twice within the last 7 days, then the value for serum creatinine used should be 4.0. • Any value less than 1 is given a value of 1 (i.e. if bilirubin is 0.8, a value of 1.0 is used) to prevent the occurrence of scores below 0 (the natural logarithm of 1 is 0, and any value below 1 would yield a negative result). Patients with a diagnosis of stage 2 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) whose ‘natural’ MELD score is low are granted exception points to gain additional priority. This is discussed in the HCC section below. The MELD score is used to predict 3-month mortality from the patient’s liver disease on a continuous scale:8 The MELD score was adopted into the liver transplant allocation scheme in 2002 in response to the ‘Final Rule’, a proclamation issued by the US Department of Health and Human Service. The policy states that the goal of organ allocation would be ‘distributing organs over as broad a geographic area as feasible … and in order of decreasing medical urgency’.9 Many other countries around the world have adopted MELD as the technique to help decide which patient from the waiting list should receive a particular organ. In some countries, an adaptation of MELD has been used based on research from the national database. In the UK, the UKELD (UK model for End-stage Liver Disease) is used with the addition of serum sodium to the mathematical model. A UKELD score > 49 predicts a > 9% 1-year mortality and is a minimum criterion for entry to the waiting list in the UK. Of the active patients on the US waiting list, approximately 5000–6000 will receive a liver transplant from either a deceased or living donor this year. Nationally, living donors comprise only about 5% of total recipients but can be as high as 40% in certain programmes such as our own that reside in regions of the country with long waiting lists and limited organ supply. Patient survival nationally for all liver transplant recipients at 1, 3 and 5 years is 87%, 78% and 73%, respectively.10–12 Contraindications to liver transplantation include both clinical and psychosocial reasons.13 Clinically significant reasons to avoid surgery include advanced cardiopulmonary disease, active sepsis, technical issues such as extensive portal and visceral venous thromboses, and advanced or metastatic malignancy. Relative contraindications are centre specific and include advanced age or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), although many programmes decide on a case-by-case basis. The most dramatic patient listed for liver transplantation presents with acute or fulminant liver failure. According to UNOS rules, the patient listed with acute fulminant liver failure (Status 1) must have a life expectancy without liver transplant of 7 days or less. Typical scenarios include, but are not limited to, acute acetaminophen overdose, mushroom poisoning, fulminant hepatitis A or B infection, Wilson’s disease, acute Budd–Chiari syndrome or a failed liver transplant (primary graft non-function or hepatic artery thrombosis, HAT).14 Patients with chronic liver disease cannot be listed as high urgency (Status 1) except after a failed transplant. A more traditional definition of acute liver failure includes the presence of encephalopathy occurring within 8 weeks of the onset of symptoms in a patient with previously normal liver function. Currently, acute liver failure patients account for about 5–6% of all liver transplants in the USA.15 Untreated, patient mortality approaches 80% in patients with severe fulminant liver failure or grade IV hepatic encephalopathy. Interestingly, approximately 15% of patients have no identifiable cause for their acute liver failure.16 Patients with fulminant liver failure develop rapid onset of multisystem organ failure requiring aggressive supportive therapies including intensive care unit (ICU) admission, ventilatory support and renal replacement therapy. Common causes of subsequent death include cerebral oedema and bacterial and/or fungal sepsis. Lack of gluconeogenesis with the development of hypoglycaemia is an ominous sign and death usually rapidly ensues without immediate transplant. Slight delays in obtaining a replacement organ can result in permanent brain injury even after liver replacement. Measures to monitor and control cerebral pressure may provide additional time while waiting for an organ and improve outcome.17 Budd–Chiari syndrome is a group of disorders caused by acute or gradual occlusion of the hepatic venous outflow of the liver18 secondary to an underlying hypercoagulable state. Budd–Chiari is a pathological diagnosis since, early in the course of the disease, venous thrombosis is at the sinusoidal level only and the hepatic veins may be patent. Therefore, clinical suspicion of the disease (large tender liver, abnormal ‘nutmeg liver’ perfusion pattern on imaging and abnormal liver function tests) should prompt a liver biopsy. Other causes of chronic passive congestion such as right heart failure should be ruled out with appropriate testing. Since the liver is engorged with blood, biopsy via the retrohepatic vena cava is preferable to avoid potential life-threatening bleeding via the percutaneous route. Patients with pathologically proven Budd–Chiari syndrome with intact hepatic architecture may benefit from decompression with side-to-side portocaval shunt to create venous outflow for the liver. Use of prosthetic material to create a functionally equivalent mesocaval shunt should be discouraged due to low patency rates in the setting of a hypercoagulable state. Transjugular intrahepatic portocaval shunts (TIPS; Fig. 8.2) are well tolerated and may be helpful in decompressing portal hypertension. However, they do not decompress liver parenchyma adequately and need frequent revisions due to low patency rates.19 Although the long-term role of TIPS may be limited in this setting, it does not worsen outcome after subsequent liver transplantation.20 Figure 8.2 Transjugular intrahepatic portocaval shunt (TIPS) is a non-selective shunt that relieves portal hypertension by bypassing the liver with an intrahepatic stent. The arrows show augmented flow through shunt. Problems with TIPS include poor 1-year unassisted patency rate (approximately 40–50%) and the development of hepatic encephalopathy in up to one-third of patients. Improper position with the ends of the stent in the right atrium or proximal portal vein can preclude safe transplant. According to the US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), between 1999 and 2008, the three most common reasons for liver transplantation were cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, followed by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and alcoholic cirrhosis with or without concomitant infection with HCV.12 Transplantation of patients with end-stage liver disease and HCC has been somewhat controversial. These patients receive significant priority with the current organ allocation system compared to patients without HCC and enjoy significantly less waiting-list mortality. In 1996, Mazzaferro et al. published a clinical study on a cohort of patients who had undergone liver transplantation for early stage, unresectable HCC (single tumour ≤ 5 cm and no more than three tumours each ≤ 3 cm). The authors found a high overall and recurrence-free survival rate at 4 years in patients who had met predetermined criteria for limited stage HCC. These criteria became known as the ‘Milan criteria’. The authors concluded that liver transplantation was an effective treatment for early-stage, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Interestingly, the ‘Milan criteria’ were established on a relatively small study of 48 patients examining explanted livers with incidental tumours, and demonstrated patient and graft survival equivalent to non-tumour patients. This study has been validated with other clinical studies and provides the rationale for the current UNOS allocation scheme for patients with end-stage liver disease and HCC.21 Previously, many transplant centres considered the criterion for inclusion on the waiting list to be appropriate even when the estimated length of a patient’s survival in the absence of transplantation was 1 year or less. More recently, a ‘natural’ or calculated MELD score of 15 points or higher is considered a reasonable threshold to recommend transplant since operative mortality and waiting-list mortality are essentially equivalent. However, patients derive long-term survival benefit with transplant at MELD scores between 10 and 15 points, especially if they have experienced life-threatening events such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) or variceal bleeding.12 Poor quality of life and the development of other complications of liver disease such as severe ascites, malnutrition or intractable encephalopathy are also indications for transplantation regardless of MELD score.22 Given the severe organ shortages, most patients in the USA with MELD scores under 20 will not be primarily offered a liver transplant via the UNOS allocation system. These patients may benefit by pursuing living donation or considering less desirable ‘import’ organs that have been rejected by the primary transplant centre. Approximately 40% of all chronic liver disease in the USA is caused by HCV infection and HCV-associated cirrhosis is the most common indication for liver transplantation among adults.12,23 It is estimated that 8 million people in the USA are infected and approximately half are unaware that they are infected. Post-transplantation, patients with HCV infections invariably develop recurrent viraemia that may range from disease that remains relatively quiescent to development of a more aggressive course with rapid graft dysfunction. HCV reinfection occurs during reperfusion of the graft in the operating room, and viral titres have been shown to reach pre-transplant levels within 72 hours post-transplant.24 Many factors (such as donor type and age, inflammatory grade of the recipient’s explanted liver, viral genotype and viral load, steroid-containing immunosuppression regimens) have all been linked with the rate and extent of HCV reinfection.25–28 Eradication of HCV infection prior to liver transplantation is considered the ideal approach, but treatment of patients with decompensated cirrhosis is fraught with difficulty. In this setting, treatment has been associated with exacerbations of encephalopathy, infections and other serious adverse events, and results in low rates of viral clearance.29–31 Newer medications for the treatment of HCV provide new hope and promise for patients with HCV waiting for liver transplant, or post-transplant recipients. Post-transplant outcomes of patients with HCV infection rival those of non-HCV patients, especially when younger donors are used.32 Advanced donor age (> 60 years) is associated with poorer patient and graft survival, although outcomes with older donors are still superior to remaining on the waiting list. The risk of development of liver cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis B infection ranges from 4.5% to 36.2%, depending on viral load (HBV-DNA level).33 Hepatitis B-associated cirrhosis is one of the most common indications for liver transplantation in Asia due to the presence of endemic hepatitis B infection. In the USA, hepatitis B accounts for only 3% of patients on the liver transplant waiting list (SRTR data, waiting list 2010). As with HCV, initial results with liver transplantation for hepatitis B were disappointing due to a high graft reinfection rate.33 However, outcomes have significantly improved since the introduction of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and nucleoside analogues over the last 20 years to prevent and treat graft reinfection.34 Current 5-year survival rates for patients transplanted for HBV-related cirrhosis exceed 75%. Liver transplantation has been established as a viable treatment option for HCC.21 As previously discussed, the landmark study for this condition established the so-called ‘Milan criteria’ and demonstrated that when transplantation was restricted to patients with early HCC a 4-year survival rate of 75% could be achieved.21 Milan criteria are defined as a single lesion less than or equal to 5 cm, up to three separate lesions, none larger than 3 cm, no evidence of gross vascular invasion and no regional nodal or distant metastases. These outcomes are similar to reported and expected survival rates for patients undergoing transplantation for cirrhosis without HCC. Other groups have suggested that these criteria are too strict and should be expanded. • A single tumour ≤ 5 cm in diameter. • Up to five tumours of ≤ 3 cm. • A single tumour > 5 cm and ≤ 7 cm where there is no evidence of tumour progression (volume increase should be < 20% over a 6-month period). There should be no extrahepatic spread or new nodule formation. The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) group have expanded the eligibility indications to include a solitary tumour up to 6.5 cm or three or fewer nodules with the largest tumour up to 4.5 cm and a total tumour diameter of up to 8 cm.35 Since patients with HCC have significant priority on the waiting list compared to non-HCC patients, it is unlikely that UCSF criteria will be adopted nationally for deceased donor allocation. However, UCSF criteria are used by some programmes performing live donor liver transplantation. A population survey of adults suggests that 10% of Americans drink more than two drinks per day, which is defined as ‘heavy drinking’.38 Heavy drinking and its consequences are important public health problems, as 5% of the deaths occurring annually in the USA (approximately 100 000 per year) are either directly or indirectly attributable to alcohol abuse.38 Among heavy drinkers, liver disease is highly prevalent. Thus, 90–100% of heavy drinkers have steatosis, 10–35% have alcohol-induced enzyme abnormalities and 8–20% have alcoholic cirrhosis.39 Untreated, the 5- and 10-year survival rates for patients with alcoholic cirrhosis are 23% and 7%, respectively.39 These rates are significantly worse than survival rates for patients whose cirrhosis was not caused by alcohol. The incidence of liver transplantation for patients with PBC has declined slightly in recent years, possibly reflecting benefits of early treatment.40 Regardless, liver transplantation remains an important option in patients with progressive disease despite medical therapy. In the USA, the average age of patients undergoing transplantation for PBC is in the range of 53–55 years. Recurrence of disease after liver transplantation can occur in a significant number of patients.41 An important clinical question is ‘What is the optimal time to perform liver transplantation in the patient with PBC?’ In the USA, the MELD score is used by many groups to determine the optimal timing of this event. However, some patients experience significant morbidity from their liver disease that is not reflected by the MELD scores. Patients with evidence of decompensation such as low serum albumin levels (< 2.8 g/dL), portal hypertension, encephalopathy, bone fractures or intractable pruritis would benefit from early evaluation and transplantation. However, in areas where livers are allocated at high MELD scores, live donor liver transplantation may be the only realistic opportunity for transplantation for such patients.42 Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) has become the only effective therapeutic option for patients with PSC-related complications. Excellent long-term outcome has been reported, with 5-year patient survival rates of approximately 80%. However, PSC recurs in 15–20% after OLT, with significant mortality at 3 years if untreated without re-transplantation.43 The need for re-transplantation in patients with PSC is more common than in patients with non-obstructive biliary disease.44 Excessive fat in liver cells in the absence of alcohol consumption is known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and is the most common type of liver disease in the USA, affecting nearly 30% of the general population. In many patients, this fat build-up can lead to inflammation and elevated liver enzymes, which is referred to as steatohepatitis (Fig. 8.3). Although the exact aetiology is unknown, risk factors are truncal obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes. As a result of these epidemics in the USA, the proportion of liver transplantations performed for NAFLD cirrhosis rose dramatically from roughly 1% in 1997–2003 to more than 7% in 2010. It is estimated that by 2025 more than 25 million Americans may have NAFLD, with as many as 20% of these cases developing end-stage liver disease. Figure 8.3 (a) Normal liver histology. (b) Marked macrovesicular steatosis. Donor liver grafts with greater than 20–30% macrovesicular steatosis are at increased risk of postoperative primary graft non-function. Steatosis can be one of the earliest histological changes seen in patients with liver disease.

Liver transplantation

Introduction

Indications for liver transplantation

Budd–Chiari syndrome

Chronic liver disease

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

Alcoholic liver disease

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Liver transplantation

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue