Liposuction

Mary K. Gingrass

Liposuction is the surgical aspiration of fat from the subcutaneous plane leaving a more desirable body contour and a smooth transition between the suctioned and the nonsuctioned areas. Liposuction is one of the most popular cosmetic procedures performed by board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States. Although liposuction is not a technically difficult procedure to perform, it requires thoughtful planning and careful patient selection to achieve consistently pleasing results. Poor planning or poor execution can result in uncorrectable deformities.

HISTORY

The aspiration of fat using blunt cannulas and negative-pressure suction was first popularized in Europe in the late 1970s.1 Three French surgeons, Drs. Yves-Gerard Illouz, Pierre Fournier, and Francis Otteni, were the first to present their lipoaspiration experience at the 1982 American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons annual meeting in Honolulu, Hawaii. The procedure was initially met with skepticism in the United States. In late 1982, a “blue ribbon committee” was commissioned by the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons to visit Dr. Illouz in Paris and the committee returned with a cautiously optimistic report. American surgeons’ interest in liposuction and public demand for minimally invasive body contouring have steadily risen since then.

PATIENT SELECTION

Patient selection is a critical determinant of a good surgical result, especially in body contouring. Not all patients who request liposuction are good candidates. The consultation begins with an assessment of the patient’s goals. What does the patient wish to change about his or her body? What does the patient expect to accomplish with liposuction? The surgeon then provides the patient with a realistic appraisal of what can and cannot be accomplished. Some patients may require alternative procedures (such as an abdominoplasty) or liposuction combined with an open surgical procedure. An astute surgeon is wary of patients who are particularly poor candidates for liposuction such as (a) perfectionists with imperceptible “deformities,” (b) those with underlying mental illness that prohibits realistic expectations (body dysmorphic disorder, or active eating disorders), and (c) significantly overweight patients who are incapable of weight reduction and/or weight maintenance after liposuction. If a patient is steadily gaining weight before liposuction, he or she are likely to continue this trend after liposuction.

A detailed weight history is an important part of any liposuction consultation. Ideal candidates are at a stable weight with a working diet and exercise regimen in place. Patients who have a history of frequent or significant weight fluctuations are at high risk for weight gain after liposuction. Maintaining a stable weight and practicing a diet and exercise regimen for at least 6 to 12 months indicates the necessary commitment to lifestyle change.

Liposuction should not be offered as a treatment for obesity. In a perfect world, it is used to remove genetically distributed or diet-resistant fat. In practical terms, however, it is frequently used to remove fat that could be lessened with diet and exercise. Ideal liposuction candidates are within 20% of their ideal body weight or less than 50 lb above chart weight. Abnormally distributed bulges of fat or fat that resides outside the confines of the ideal body shape are the “target” areas that are most commonly suctioned.

PATIENT EVALUATION

A thorough physical examination is always performed. Although the focus of the examination should be on “problem areas,” it is important to take the entire body shape into consideration. An overall harmonious body contour is the desirable outcome. The patient is examined for areas of disproportionate fat, asymmetry between the two sides, dimpling/cellulite, varicosities, and zones of adherence. Asymmetries are noted and, if they are significant, they are brought to the attention of the patient. If the abdomen is being considered as a potential surgical site, it should be carefully examined for hernias, significant abdominal wall laxity, abdominal scars, history of abdominal radiation, and anything that might affect abdominal wall integrity.

One of the most important physical findings, which will have significant bearing on the final outcome, is the patient’s skin tone, or dermal quality. It is important to pinch and palpate the skin, assessing for the degree of laxity and dermal thickness. A thicker dermis is more likely to retract after liposuction and give a desirable result. Thin, stretched skin with striae (indicating dermal breakage) is unlikely to retract and may look worse after liposuction. If it is determined that the skin quality is unsuitable for liposuction, alternative procedures are proposed, such as skin excision, if indicated. Liposuction does not treat cellulite; thus one should not make promises to this effect.

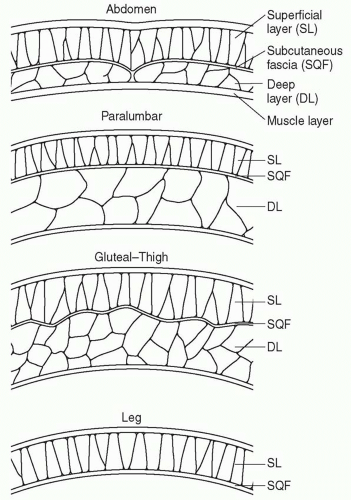

The quality of the fat should also be assessed because it may affect the outcome. The anatomy of the subcutaneous adipose tissue varies throughout the body. Some areas of the body have both a deep adipose compartment and a superficial adipose compartment, which are separated by a discrete subcutaneous fascia. The superficial fat in the trunk and thigh consists of smaller lobules, tightly organized within vertically oriented, thin, fibrous septa. The deep fat consists of larger lobules arranged more loosely within widely spaced and more irregularly arranged septa (Figure 65.1).2 In these areas, the deep layer of fat is the target for liposuction. The overlying superficial fat is (usually) relatively thin and will act as a protective layer to hide small contour deformities, especially for the inexperienced liposuction surgeon. In contrast, other areas of the body that are commonly suctioned (arms and lower legs) have only one layer of fat. Suctioning these areas with smaller cannulas will help avoid contour irregularities.

Superficial liposuction, a technique popularized by Marco Gasparotti and others, uses small cannulas to aspirate fat from the superficial planes (1 to 2 mm). Proponents of this technique contend that aspiration in the superficial plane leads to predictable contraction of the overlying skin. Superficial liposuction leaves very little margin for error and should not be attempted until the liposuction surgeon has gained considerable experience in the deep and intermediate planes.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent should be regarded by the surgeon not only as a legal responsibility but also as a mutually beneficial transaction. The patient is informed of the risks, benefits, and available alternatives to the procedure being considered. A well-informed patient knows what to expect in the postoperative period. In the event of a postoperative complication, there is less likelihood of compromise of the doctor-patient relationship if the patient was well informed initially.

ANESTHESIA

The appropriate type of anesthesia should be chosen based on surgeon preference, patient choice, estimated volume to be removed, and whether other surgical procedures are being combined with liposuction. Liposuction can be performed safely as an outpatient procedure in an office setting or in an outpatient surgery facility as long as strict adherence to patient safety is maintained. Local or regional anesthesia is generally appropriate for aspiration of smaller volumes, and general anesthesia is preferable when larger volumes are removed. When large-volume liposuction (>5,000 mL of total aspirate) is performed, or when liposuction is combined with a significant open surgical procedure(s), hospital admission or 24-hour observation in a hospital setting is recommended.

Attention to perioperative fluid management is imperative when significant volumes are suctioned. Approximately 70% of the injected subcutaneous fluid will be absorbed and must therefore be taken into account when calculating intraoperative intravenous (IV) fluid. Anesthesiologists unfamiliar with liposuction may not be aware of this fact and excessive fluids may be administered. When the superwet technique is used (see Wetting Solution below), the following guidelines for fluid resuscitation are recommended: (a) for volumes <5 L of total aspirate, administer maintenance fluid plus subcutaneous wetting solution; (b) for volumes ≥5 L total aspirate, administer maintenance fluid plus subcutaneous wetting solution plus 0.25 mL of IV crystalloid per milliliter of aspirate above 5 L.3

SURGICAL PLANNING AND INSTRUMENTATION

There are a number of tools available to the liposuction surgeon. Each tool has its advantages and disadvantages and some surgeons simply prefer one tool or technique over another. The following discussion is only an introductory comparison, not an in-depth analysis, of the available techniques.

Traditional suction-assisted lipoplasty (SAL) became popular in the United States in the 1980s. The technique uses varying diameter, blunt-tip cannulas attached via large-bore tubing to a source of high vacuum, which effectively suctions fat through a hole or holes in the tip of the cannula. Syringe SAL is a variation whereby fat is aspirated with a cannula attached to a syringe. Suction is created when the plunger is withdrawn, collecting the fat into the syringe. This technique is frequently used if fat is being harvested for fat grafting.

SAL has a long track record and is considered the “gold standard.” Traditional SAL cannulas are typically bendable and come in many sizes and tip configurations, and most hospital operating rooms and surgery centers own this type of equipment. SAL is an excellent technique for small- to mediumvolume cases and removal of soft fat. The sheer simplicity of SAL makes it a valuable tool that is essential to have in any plastic surgeon’s armamentarium. It is a less efficient tool for the removal of fat from more fibrous areas and requires a fair amount of physical effort on the part of the surgeon, which becomes a disadvantage in larger volume cases. Bruising is expected as a result of disruption of blood vessels by the shearing and suction forces. Cross-tunneling is a necessary step with SAL to avoid contour irregularity, which one study reported to be as high as 20%.4 The most frequently reported unsatisfactory results in this study were insufficient fat removal and excessive waviness. Asymmetry, excessive fat removal, and unacceptable scarring occurred with less frequency.

Ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL) was introduced in the United States in the mid-1990s to address some of the shortcomings of SAL. Ultrasonic energy is produced in a piezoelectric crystal within the UAL hand piece. The ultrasonic energy is transmitted down the attached probe or cannula to its tip,

where it causes micromechanical, thermal, and cavitational effects on subcutaneous fat. The intervening fibroconnective tissues remain relatively unharmed and available for postoperative skin retraction. The emulsified fat is suctioned away with low-power suction. UAL requires much less physical effort on the part of the surgeon than does SAL because much of the “work” is done by the ultrasonic energy. UAL is an extremely efficient tool for the removal of fat in fibrous areas such as the upper back, the hypogastrium, and the breast. UAL has been shown to cause less disruption of vasculature than SAL,5 which translates into less bruising in most cases. There is energy dissipation in all directions at the tip of the UAL probe or cannula, which gives it a certain “airbrush” effect. Some surgeons believe it is a superior tool for sculpting and find there is less need for cross-tunneling compared with SAL.

where it causes micromechanical, thermal, and cavitational effects on subcutaneous fat. The intervening fibroconnective tissues remain relatively unharmed and available for postoperative skin retraction. The emulsified fat is suctioned away with low-power suction. UAL requires much less physical effort on the part of the surgeon than does SAL because much of the “work” is done by the ultrasonic energy. UAL is an extremely efficient tool for the removal of fat in fibrous areas such as the upper back, the hypogastrium, and the breast. UAL has been shown to cause less disruption of vasculature than SAL,5 which translates into less bruising in most cases. There is energy dissipation in all directions at the tip of the UAL probe or cannula, which gives it a certain “airbrush” effect. Some surgeons believe it is a superior tool for sculpting and find there is less need for cross-tunneling compared with SAL.

There are also disadvantages to UAL. There is potential for frictional injury at the skin entry site, so constant irrigation at the incision or a skin protector must be used. Seroma rates can be high with prolonged ultrasound treatment times. There is some elevation of tissue temperature with UAL and, if improper technique is used, thermal injury can occur. With proper training, these problems rarely occur. UAL is safe and effective when the surgeon is properly trained and the procedure is performed properly.6

Power-assisted liposuction (PAL) was developed in the late 1990s to address some of the concerns about UAL. PAL is basically traditional SAL powered by a reciprocating cannula. The main advantages of PAL over SAL are its efficiency in fibrous areas and its ease of operation for the surgeon. There is no particular salvage of fibroconnective tissue or neurovascular structures as there is with UAL. The main advantage of PAL over UAL is that there is no heat generation. PAL is an excellent tool for the surgeons who remain uncomfortable with the potential for heat and the power of UAL.

The use of laser assistance to improve liposuction results has recently been proposed. Proponents advocate that the application of laser energy, applied either externally or internally to the fatty layer, disrupts adipocyte cell membranes. However, studies by Prado et al. failed to demonstrate clinical advantages with internally applied laser-assisted liposuction over traditional SAL in a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.7 Studies by Brown et al. failed to show any adipocyte disruption by histologic or scanning electron microscopy in porcine and human fat treated with laser-assisted lipoplasty versus traditional SAL. This study also failed to show any clinically significant differences in patients treated with internal or external laser-assisted lipoplasty.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree