24 Liposuction

A comprehensive review of techniques and safety

Synopsis

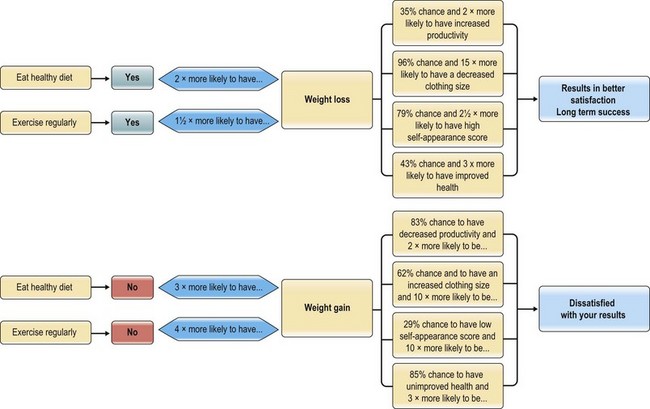

Incorporation of a diet and exercise program in conjunction with liposuction will allow patients to achieve their optimal shape and contour. Patients who do not adhere to diet and exercise are least happy with their results.

Incorporation of a diet and exercise program in conjunction with liposuction will allow patients to achieve their optimal shape and contour. Patients who do not adhere to diet and exercise are least happy with their results.

A thorough history and physical exam should be performed and a preoperative clearance obtained, especially for large volume or long combined cases.

A thorough history and physical exam should be performed and a preoperative clearance obtained, especially for large volume or long combined cases.

Marking the patient in front of a mirror allows both the surgeon and patient to see and understand the areas of concern and intended treatment. Cellulite and other contour irregularities can be pointed out preoperatively to the patient.

Marking the patient in front of a mirror allows both the surgeon and patient to see and understand the areas of concern and intended treatment. Cellulite and other contour irregularities can be pointed out preoperatively to the patient.

Over-the-counter herbal and diet medications may have unfavorable interaction with surgery and/or anesthesia and should be discontinued 3 weeks prior to surgery.

Over-the-counter herbal and diet medications may have unfavorable interaction with surgery and/or anesthesia and should be discontinued 3 weeks prior to surgery.

Knowledge of the differing thickness and consistency of fat throughout the body is crucial to determining proper depth and technique for each region of the body.

Knowledge of the differing thickness and consistency of fat throughout the body is crucial to determining proper depth and technique for each region of the body.

Superficial liposuction should be reserved for significant superficial irregularities and be performed by those experienced in liposuction techniques.

Superficial liposuction should be reserved for significant superficial irregularities and be performed by those experienced in liposuction techniques.

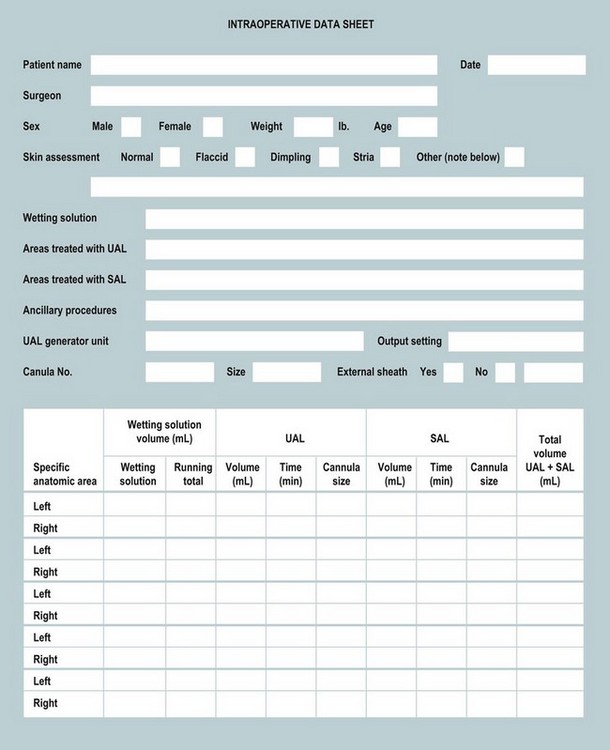

Wetting solutions should always be used and a strict record of volume infused and aspirated should be kept by the operating room personnel.

Wetting solutions should always be used and a strict record of volume infused and aspirated should be kept by the operating room personnel.

Surgical access sites should be concealed, often asymmetric, and utilized to allow the best access and treatment results. Excessive use of a single access incision may result in a deformity.

Surgical access sites should be concealed, often asymmetric, and utilized to allow the best access and treatment results. Excessive use of a single access incision may result in a deformity.

Patients with surgical scars on their abdomen must be thoroughly examined to rule out the presence of a hernia.

Patients with surgical scars on their abdomen must be thoroughly examined to rule out the presence of a hernia.

Treatment with UAL begins superficially and ends in the deeper plane. In contrast, evacuation proceeds from the deeper layers to the more superficial layers.

Treatment with UAL begins superficially and ends in the deeper plane. In contrast, evacuation proceeds from the deeper layers to the more superficial layers.

Postoperative contour deformities should be clinically evaluated, and if mild, can respond to lymphatic massage or other non-invasive methods. A systematic approach should be used to correct contour deformities when they occur.

Postoperative contour deformities should be clinically evaluated, and if mild, can respond to lymphatic massage or other non-invasive methods. A systematic approach should be used to correct contour deformities when they occur.

Introduction

Suction-assisted lipectomy, lipoplasty, or more commonly referred to as liposuction, originally introduced by Illouz in the early 1980s, continues to be one of the most popular means of body contouring and overall treatment modalities offered in aesthetic surgery today.1 Annually, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgery and American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, it consistently ranks among the top procedures performed in plastic surgery for the last 10 years.2 With greater understanding of the biochemical and physiologic properties of liposuction, as well as bio-medical technological advancements, suction-assisted lipoplasty has undergone tremendous evolution leading to overall improvements in technique, patient safety, and outcomes. Over the past two decades, it has grown from a procedure that facilitates small or spot reductions to one that has become an almost irreplaceable tool in the aesthetic surgery armamentarium in neck, breast, and circumferential body contouring. Liposuction has become a useful adjunct to other areas of plastic surgery, including breast reconstruction, and postoperative contouring in upper and lower extremity reconstruction. A number of important innovations and modifications to the standard suction-assisted liposuction (SAL) have progressively refined the procedure; these include: the use of wetting solutions; advances in cannula design; ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL); power-assisted liposuction (PAL); vaser-assisted liposuction, and laser-assisted liposuction (LAL). There has been a strong movement concentrated on defining appropriate safety guidelines for liposuction and other body contouring procedures focusing on deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis and fluid resuscitation ensuring safety and efficacy of the different treatment modalities for our patients.

Basic science and anatomic considerations

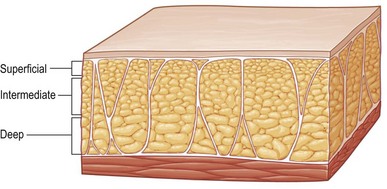

Anatomy texts divide subcutaneous fat throughout the body into superficial and deep layers or compartments separated by Scarpa’s fascia, or the superficial fascial equivalent.3 However, for the purposes of liposuction and body contouring, subcutaneous fat is arbitrarily divided into three layers: superficial, intermediate, and deep (Fig. 24.1).4,5 The importance of this distinction is that the superficial layer is one that rarely is violated. If this layer is treated, there may be vascular compromise and/or a significantly increased risk for contour irregularities. The relative consistency and thickness of each of these separate layers varies for different anatomic areas. For example, the fat of the back has a more fibrous, compact superficial and intermediate layer, with an underlying loose, areolar layer. This contrasts with the fat of the inner thigh, which is not as fibrous and is less compact.3 This is critical information for the aesthetic surgeon in order to perform safe and appropriate suctioning of the targeted area minimizing potential contour irregularities and skin necrosis. The variation in fat consistency and depth will be discussed further as it relates to safe suctioning techniques and the choice of modality which may be preferred for the most effective treatment.

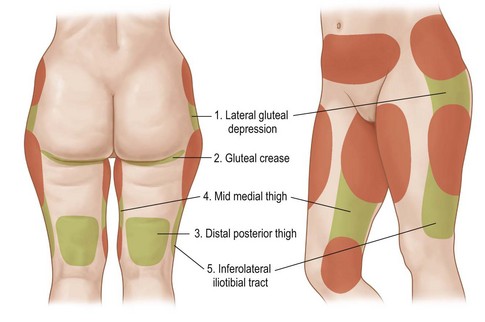

Anatomic “zones of adherence,”6 which are present in both men and women, are important to identify and mark during the preoperative consultation. These are areas of relative dense fibrous attachments to underlying deep fascia, which help define the natural shape and curve of the body. There are gender-specific variations with respect to each of these zones (Fig. 24.2). It is important to recognize these zones, as they are identified as high-risk areas for contour irregularities after surgical intervention if not properly respected. However, these are not areas to avoid in all cases, and on occasion, help guide the surgeon in establishing “contour goals” for surgical intervention. Regardless of the tool used for liposuction, it is helpful to consider the treatment area in terms of the three surgical layers. These arbitrary layers help delineate areas of safety when performing liposuction. The most common areas treated are the intermediate and deep layer. Treatment of these layers allows uniform reduction without risk of injury to the subdermal plexus and unwanted skin injury.

Classification

It is helpful to classify patients based on the three types of lipodystrophy and skin redundancy (Fig. 24.3).

Type I: Localized lipodystrophy. Often younger patients with good skin tone and minimal skin irregularities.

Type II: Generalized lipodystrophy. These patients tend to have slightly diminished skin tone with some skin irregularities and circumferential lipodystrophy throughout their trunk and extremities.

Type III: Skin redundancy and lipodystrophy. Patients displaying significant skin redundancy that would be more amenable to excisional surgical techniques to improve shape and contour. If necessary, liposuction may be a useful adjunct in order to achieve an optimal result.

Cellulite is a skin condition that is often seen when evaluating patients for liposuction. Cellulite is a dimpling of the skin, particularly in the areas of thighs and buttocks. It has a poorly understood pathophysiology but is thought to be related to fibrous, dermal attachments to the underlying fascia and surrounding hypertrophied fat.3,7 It has a hormonally mediated component. There is no predictable, long-term treatment of cellulite. Liposuction in areas of overlying cellulite may soften or accentuate the superficial deformity. This should be clearly delineated to the patient as the goals of surgery are reviewed.8

Diagnosis, operative indications and patient selection

Liposuction patients often present with a variety of expectations, concerns, and/or complaints. In order to achieve optimal contour with liposuction, appropriate patient selection is imperative. As a general rule, liposuction is performed in healthy patients who maintain realistic goals and expectations. Studies have shown that patients who undergo proper long-term lifestyle changes will in fact achieve the highest level of postoperative satisfaction from their liposuction-assisted body contouring procedure. Rohrich et al.9 concluded that those patients who were committed to a positive lifestyle change involving a healthy diet and regular exercise, or who were already practicing a “healthy lifestyle” that continued postoperatively, experienced the best self assessment and satisfaction scores with liposuction postoperatively (Fig. 24.4). A successful body contouring patient must satisfy four key elements to achieve and maintain optimal results:

Preoperative assessment

Initial evaluation

It is often prudent to notify the consulting physician of expected operative times and the amount of expected aspirate and infiltrate. Often, our medical consultants view liposuction as a very benign operation with minimal operative time and morbidity, when in fact a large-volume liposuction case can have significant fluid shifts and time under general anesthesia.10 Massive weight loss patients should undergo the same preoperative evaluation and clearance for liposuction as they would for any excisional type body contouring procedure (including nutrition, hemoglobin, iron, B12, etc.).11 It is safest to refrain from operations until these lab results are normalized. Herbal remedies and supplements are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and thus may place the patient at potential risk of untoward complications, including bleeding or hypercoagulability and should be avoided in the perioperative period.12 Avoiding aspirin, NSAIDs, and hormonal therapy can help prevent such complications as well. It is the authors’ policy for patients to discontinue use of all NSAIDs, aspirin products, fish oil, and supplements, 3 weeks prior to surgery. Of course, if there is a medical indication and necessity for these drugs, consultation with the primary physician or appropriate specialist should be completed before discontinuation of the medical therapy. A frank discussion of the risk of oral contraceptives and estrogens is held with the patient regardless of the magnitude of the procedure. We strongly recommend that these medications be discontinued 1 month prior to the operative procedure.13

Physical exam

A detailed physical exam is performed at the first visit and consultation. Specific attention to prior scars, presence or absence of hernias, evidence of venous insufficiency, and presence of pre-existing asymmetry or contour irregularity should be discussed and noted in the chart. At the initial and subsequent visits, height and weight with calculation of body mass index (BMI) is paramount for safety, as well as for observation of long-term trends during follow-up. For liposuction candidates, six key elements are documented4–6:

The physical exam is best performed in front of a full-length mirror (Fig. 24.5). This allows an open dialogue between patient and physician, wherein the patient’s concerns can be addressed and previously unrecognized problem areas can be assessed and addressed. Any areas of cellulite should be pointed out to the patient, and a specific discussion of expected outcome in these areas should be noted. At the initial evaluation, high-quality medical images should be obtained, with anterior, posterior, lateral, and oblique views. This will allow for documentation of results, as well as objective evaluation of outcomes by both patient and physician. Professional medical photography can be a very useful tool for accurate and consistent pre and postoperative documentation.14

While the patient is in a supine position with the head elevated, abdominal integrity is examined (Fig. 24.6). This is helpful for detecting hernias or myofascial diastases. Findings may be difficult to interpret in larger individuals, males, or patients with multiple scars. An ultrasound examination or CT scan may further clarify this region and prevent potential intra-abdominal injury in these patients. During the initial consultation, when the patient is in front of the mirror, it is important to point out potential problem areas that may cause less than optimal results, so the patient may visualize and appreciate these areas.

A follow-up visit is typically scheduled 2–3 weeks after the initial consultation. During this visit, computer images (Fig. 24.7) are reviewed, which allows the patient to establish realistic expectations. These objective images portray the advantages, disadvantages, and limitations of body contouring surgery. The patient should understand that imaging is for educational purposes only and is not a guarantee of the final result. The second visit allows further dialogue between the patient and physician so that all questions may be answered and issues addressed. For example, a second opportunity to address any last minute concerns by the patient in regards to recovery time, pain control, bruising, and postoperative changes will help strengthen the patient’s confidence in the procedure and decrease the likelihood of any uncertainties or surprises within the perioperative period.

Patient education and informed consent

Patient education is stressed throughout the course of the initial evaluation, physical examination, and follow-up visit so that the patient has sufficient information about the procedure, postoperative course, and long-term results to make a truly informed decision. The patient and physician should discuss the procedure itself, alternative treatments, financial obligations (including further surgeries if required), and complications and risks. The risks for liposuction include, but are not limited to, bleeding, infection, pain, thermal injury, seroma, dyspigmentation, paresthesias, contour irregularities, and dysesthesias. Large volume liposuction carries increased risks of fluid shifts, volume overload, and anesthesia complications.10 These problems are discussed under “Complications”, below. Informed consent is vitally important in the evaluation and management of liposuction patients both to protect the surgeon and the patient from unexpected outcomes or patient dissatisfaction. This important process should be performed by the operative surgeon (not a nurse or staff) and clearly documented in the medical record.

Operative considerations

Preoperative marking

Guiding marks are performed prior to surgery with the patient in the erect position. In patients undergoing total body liposuction or contouring in combination with excisional surgery, marking can be done in the office the day before surgery. This allows for a more private environment and ample time to review the plan with the patient. Marking is done in front of a mirror, thus allowing the patient to contribute to the process and further confirms exactly what will be addressed during the procedure. Areas to be suctioned are marked with a circle; zones of adherence and areas to avoid are marked with hash marks. Asymmetries, cellulite, and dimpling are marked for their respective treatment and to allow patients to see problem areas. When complete, the marks are once again reviewed with the patient to ensure that all areas of concern are addressed.4,5 Access incisions are also marked at this setting. Often two incisions are needed per area to be suctioned, the incisions should be placed adjacent to suctioned areas and not too distant. With liposuction, it is beneficial to choose access points that can treat multiple areas. Care should be taken to prevent access incision placement in or adjacent to zones of adherence. The suctioning may cross the zone and disrupt it. Incisions should also allow each area to be treated from different directions for optimal contouring. Incisions should be no longer than 3–4 mm in length and placed in well-concealed areas. Of note, the incisions utilized for ultrasound-assisted liposuction are slightly longer (5–6 mm) than for standard liposuction to account for the placement of skin protectors when utilized. The surgeon should not hesitate in placing additional incisions if access is insufficient with the existing markings.

Figure 24.8 shows the preoperative markings and preferred placement of access incisions based on areas to be suctioned. Cosmetically, it is preferable to stagger incisions in an asymmetric fashion to camouflage their appearance.4,5

Anesthesia technique/location of operation

It is up to the surgeon to determine the optimal surgical setting for each patient undergoing liposuction. Factors which influence this decision are: the amount of expected lipoaspirate, length and extent of procedure, patient positioning, operating surgeon preference, anesthesiologist preference, and overall health of the patient. Depending on the geographical location, there are differing regulations for the location of liposuction procedures, usually based on the type of anesthesia and the size of the liposuction procedure. For example, one recommendation is to avoid epidural and spinal anesthesia in office-based settings because of potential hypotension and volume overload issues.15

Awake liposuction has been performed in the office-based setting with a tumescent technique. The authors prefer to do such procedures only for single area treatments or in small revisions. Detailed patient assessment and strict limitations on volumes infiltrated and amount of lipoaspirate expected should be reviewed prior to performing in an unmonitored office-based setting.16 Although there is some convenience and cost-saving to office-based surgery, with the recent advancements and attention to patient safety, this should be discouraged except for small localized areas and limited volumes.

Special importance should be given to medical co-morbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea. Current American Society of Anesthesiology recommendations are: for patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea, surgery should be performed in a hospital setting with extended recovery and observation to prevent postoperative respiratory complications.17 It is recommended that liposuction procedures, whether inpatient or outpatient, if under anesthesia care, should be performed in an accredited facility with the capability to manage any postoperative insult.18 During the liposuction procedure, it is useful to have the circulating nurse maintain an accurate liposuction data sheet to facilitate consistent and accurate communication among the surgeon, the anesthesiologist, and the operating room team (Fig. 24.9).

Patient positioning

Prone/supine

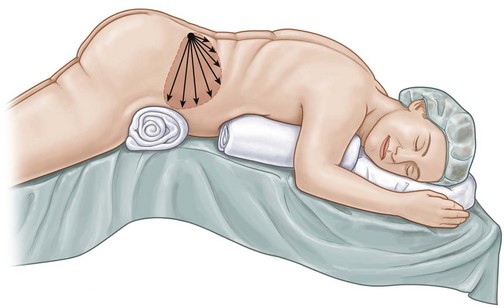

Once marked, the patient position is determined. The cadence of the operation usually begins with the patient in the prone position followed by supine. This necessitates prepping and draping the patient twice. If the team works together, turnaround time should be limited to <10 min. An alternative method is to prep the patient circumferentially while standing and to then position the patient on a sterile table with position changes not necessitating a reprep. We dislike this technique as it may be embarrassing for the patient and increases the likelihood of hypothermia. Once in the operating room, the compression devices are applied to the patient before being placed under general anesthesia. In the majority of our liposuction cases, we prefer to position the patient prone first. A soft hip roll is placed beneath the iliac crests to elevate the treatment areas off the bed, and either pillows or longitudinal rolls are used to support the upper chest (Fig. 24.10). The breasts should be placed medially and nipples protected.

Wetting solutions and perioperative fluid management

When first described, liposuction was performed without the use of any infiltrated wetting solution which resulted in blood loss of up to 45% of aspirate in some areas.19,20 In an effort to reduce blood loss, the practice of infiltrating wetting solutions (saline or LR mixture with dilute amounts of epinephrine and lidocaine) was developed. Liposuction has continued to evolve to include the addition of infiltrating subcutaneous wetting solutions prior to suctioning in order to provide hydro-dissection, improve hemostasis, and potentially provide some perioperative analgesia.

There are four different terms used to describe the types of wetting solution: dry, wet, superwet, and tumescent.19 These terms are based on the volume of infiltrate as a ratio of the volume suctioned (Tables 24.1, 24.2). The dry technique uses no wetting solution and has few if any indications in liposuction. The wet technique involves pre-infiltrating 200–300 mL of solution per region to be treated, regardless of the anticipated amount to be aspirated. The superwet technique employs an infiltration of 1 mL of solution per estimated 1 mL of expected aspirate, and finally the tumescent infiltration, popularized by Klein et al., involves extensive infiltration of wetting solution that creates significant tissue turgor and results in total infiltration of ~3 mL of wetting solution per 1 mL aspirated.19–23 Regardless of the technique used, the infiltrate should be allowed to set for 7 min and no longer than 30 min prior to suctioning because of the estimated onset of action of the anesthetic and vasoconstrictor in the solution. As detailed in Table 24.2, there is negligible blood loss (<1% of the lipoaspirate) when the superwet technique or tumescent techniques are utilized.

Table 24.1 Estimated blood loss with different liposuction techniques19

| Technique | Estimated blood loss as % of volume aspirated |

|---|---|

| Dry | 20–45 |

| Wet | 4–30 |

| Superwet | 1 |

| Tumescent | 1 |

(Data from Fodor PB. Wetting solutions in aspirative lipoplasty: a plea for safety in liposuction. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1995;19(4):379–380.)

Table 24.2 Techniques of liposuction and infiltrates19

| Technique | Infiltrate | Volume aspirate |

|---|---|---|

| Dry | No infiltrate | To treatment endpoint |

| Wet | 200–300 mL/area | To treatment endpoint |

| Superwet | 1 mL infiltrate:1 mL aspirate | 1 mL aspirate/infiltrate (treatment endpoints) |

| Tumescent | Infiltrate to skin turgor | 2–3 mL aspirate/mL |

(Data from Fodor PB. Wetting solutions in aspirative lipoplasty: a plea for safety in liposuction. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1995;19(4):379–380.)

Many authors have popularized different variations of these solutions, but all formulations include some variant of fluid (NS/LR), epinephrine, and lidocaine.19–22 Marcaine should be avoided because of its potential cardiac effects and duration of action; it has yet to be proven clinically as a suitable anesthetic in wetting solutions.24 The most common solution mixtures are shown in Table 24.3.

Table 24.3 The most common formulations of wetting solutions

| Wetting solution contents | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Klein’s formula | |

| Normal saline solution | 1000 mL |

| 1% lidocaine | 50 mL |

| 1 : 1000 epinephrine | 1 mL |

| 8.4% sodium bicarbonate | 12.5 mL |

| Hunstad’s formula | |

| Ringer’s lactate solution | 1000 mL at 38–40°C |

| 1% lidocaine | 50 mL |

| 1 : 1000 epinephrine | 1 mL |

| Fodor’s formula | |

| Ringer’s lactate solution | 1000 mL |

| Aspirates <2000 mL 1 : 500 epinephrine | 1 mL |

| Aspirates 2000–4000 mL 1 : 1000 epinephrine | 1 mL |

| Aspirates >4000 mL 1 : 1500 epinephrine | 1 mL |

| UT Southwestern formula | |

| Ringer’s lactate solution | 1000 mL at 21°C |

| Aspirates <5000 mL 1% lidocaine | 30 mL |

| Aspirates >5000 mL 1% lidocaine | 15 mL |

| 1 : 1000 epinephrine | 1 mL |

Lidocaine

Most wetting solutions utilize lidocaine as the local anesthetic component to be included in the wetting solution. It has been reported to provide analgesia for up to 18 h postoperatively when injected in dilute concentrations into the subcutaneous space.25 Initially with the large volumes of solution injected, there was concern about lidocaine toxicity. Toxicity from lidocaine affects the heart and central nervous system most commonly. The initial signs and symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include circumoral numbness, tinnitus, and lightheadedness. Increasing levels can yield tremors, seizures, and eventually cardiopulmonary arrest. Intraoperative findings would include arrhythmias, and cardiac irregularities.26 The traditional recommended maximum dose of lidocaine with epinephrine is 7 mg/kg;27 however, in the liposuction setting, numerous studies have documented the safety of lidocaine in concentrations >35 mg/kg and as high as 55 mg/kg in large volume cases.22,28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree