26 Lipoabdominoplasty

Synopsis

The results of lipoadominoplasty include:

Better body contour, because liposuction decreases abdominal measurement.

Better body contour, because liposuction decreases abdominal measurement.

Less morbidity due to preservation of the perforating vessels and the absence of dead space.

Less morbidity due to preservation of the perforating vessels and the absence of dead space.

Low percentage of complications.

Low percentage of complications.

It is easy to perform because all surgeons perform liposuction and abdominoplasty.

It is easy to perform because all surgeons perform liposuction and abdominoplasty.

Rejuvenated abdomen with a more natural profile.

Rejuvenated abdomen with a more natural profile.

Preservation of suprapubic sensitivity.

Preservation of suprapubic sensitivity.

Quick postoperative recovery and shorter scar.

Quick postoperative recovery and shorter scar.

It can be associated with vibroliposuction or ultrasound liposuction.

It can be associated with vibroliposuction or ultrasound liposuction.

Introduction

Abdominoplasty and liposuction attempt to correct those problems. For many years abdominoplasty was considered to be a relatively easy procedure to perform, but its results were not always satisfactory from a cosmetic point of view. In the evolution of aesthetic abdominal surgery many surgical treatments have been proposed, as surgeons searched for innovations.1–17 The goals have been an improvement of shape with minimal morbidity and a low complication rate. For the past few years, there has been considerable progress in methods to undermine the abdominoplasty flap and treat abdominal wall fat.

Historical perspective

Undermining evolution

From 1899 to 1957 there was continued progress in undermining the abdominal flap. Extensive undermining was standardized by Vernon,2–4 facilitating transposition of the umbilicus.

In 1965, Callia,4 in his PhD dissertation, placed the median part of the incision over the pubis and its lateral extensions parallel and beyond the crural arcades and, in this way, he hid the scar. This kind of incision inaugurated a new phase in abdominoplasty.

Pitanguy, in 1967,5 supported the horizontal incision, just above the pubis, curving laterally downwards with intense undermining and transposition of the umbilicus. His great contribution was plication of the straight abdominal muscle, without opening the aponeurosis. In 1974, he emphasized that the lateral incisions should stretch downward or upward, depending on the individual case.5

Liposuction, developed and reported by Illouz,6 changed the history of abdominoplasty completely.

Hakme (1985) presented a new approach for abdominal lipectomy called minilipoabdominoplasty. This consisted of liposuction of the whole abdomen and the flanks, an elliptical resection of the suprapubic skin, and plication of the supra- and infraumbilical muscles, all without dislocation of the umbilicus.8

Cardoso de Castro et al. (1984) published methods to avoid complications related to the flap during miniabdominplasty.18

In 1991 and 1995, Matarasso focused on the complications of combined liposuction and abdominoplasty methods, presenting two articles that recommended safe areas of liposuction.9,10 In these articles he considered the back and the flanks safe areas, but he did not regard the lateral region of the abdomen as a safe area and the central region of the abdomen was considered prohibited for liposuction.17

In 1995, Lockwood reported on the high lateral tension abdominoplasty, in which he used Scarpa’s fascia to decrease the tension of the skin closure.12,13

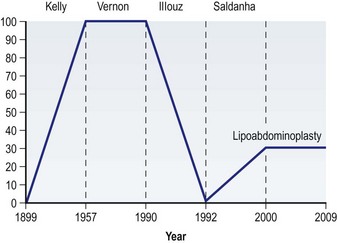

Since the 1990s progressively less undermining of the abdominoplasty flap has been described. In 1992 the technique of abdominoplasty mesh undermining was described by Illouz11,18,19. Shestak14 and Avelar15 presented partial abdominolipoplasty, utilizing liposuction for undermining. Figure 26.1 shows the trend of undermining evolution in abdominoplasty, from 1899 to 2009.

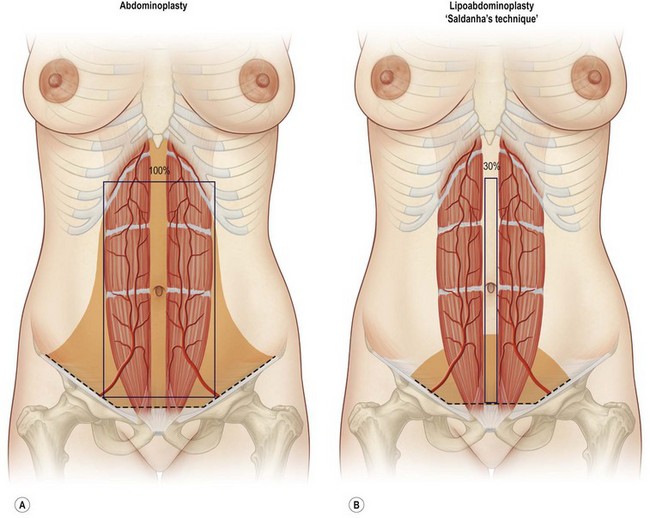

In 2001, using the term “lipoabdominoplasty” for the first time and with the publication of this technique, Saldanha et al.16 described a selective undermining along the internal borders of the rectus abdominal muscles, corresponding to 30% of traditional undermining, thus preserving the abdominal perforating vessels, safely performing liposuction and abdominolipoplasty at the same time.20–26 This selective undermining is maintained to this day.

Basic science/disease process

Anatomic principles of the lipoabdominoplasty

Lipoabdominoplasty is based on an understanding of the vascular anatomy of the abdominal wall, particularly the perforating vessels, which come from the deep epigastric arteries. Many studies have evaluated the vascular anatomy of this region based on cadaver dissections, clinical observations, and noninvasive radiological examinations.27–29

Taylor et al. (1991) studied skin vascularity, describing the angiosomes which separate the abdominal area into superior, inferior, and lateral regions.29 In the superior region, the superior epigastric vessels are responsible for blood supply. In the lateral region, the superficial and deep circumflex vessels and branches of the intercostal vessels provide blood supply. In the inferior region, the main vascularity comes from the inferior deep epigastric vessels (Fig. 26.2).

According to Huger,30 in classical abdominoplasty, normal vascular flow is interrupted by section of the perforating vessels coming from the rectus abdominis muscle. Consequently, the vascularity of the remaining flap is supplied by the intercostals, subcostal and lumbar perforating branches, situated superiorly and laterally. Therefore when combined with liposuction, extensive traditional undermining may damage the vascularity of the flap, increasing the risk of tissue necrosis. This anatomy is described in Chapter 25.

An important paper published by Graf,31 using Doppler flowmetry, looked at perfusion in the periumbilical perforating vessels on the 15th day after lipoabdominoplasty, showing that liposuction did not damage vessels whose diameters were 1 mm or more. Furthermore, there was a 9% increase in the caliber of the arteries and a 56% increase in the flow of these perforators. The explanation for this increase in flow is uncertain, but may be due to the physiopathology of surgical trauma generating vasodilatation.

Munhoz et al.32 identified and quantified the perforating vessels, which allowed for a comparative evaluation of the blood supply of the flap in the pre- and postoperative periods of patients who had undergone lipoabdominoplasty. In this study more than 81.21% of perforating vessels were preserved.

Another relevant paper was published by De Frene et al.,33 in which the authors performed breast reconstruction using flaps based on vessels which perforate the rectus abdominis muscles, in patients who had previous abdominal liposuction. The successful outcomes demonstrated that liposuction had not harmed the larger perforating vessels.

Fundamental principles of the technique

The two fundamentals of this technique are preservation of abdominal wall perforating vessels and the use of superficial liposuction. In this anatomic location, superficial liposuction, originally introduced by De Souza Pinto, involves aspiration of fat superficial to Scarpa’s fascia.7,26 The key finding which makes lipoabdominoplasty possible is that superficial cannula liposuction significantly mobilizes the abdominal wall flap. The flap can then be advanced inferiorly to the pubis, without the need for classical undermining in the area of the vascular perforating vessels. A narrow central tunnel between the vascular perforators can then be safely opened in order to accomplish rectus plication.