Leprosy: Introduction

|

Historical Aspects

![]() Leprosy is an ancient disease; sacred writings from India in the sixth century bc give a good description of a similar or identical illness. By the second century ad, Greek physicians in Europe wrote descriptions of the disease, evidently well established by that time. Stigmatization of patients with leprosy remains an unfortunate but enduring legacy of the European pandemic that occurred from 1,000–1,500 ad Hansen’s attribution of Mycobacterium leprae as its etiologic agent in 1873 marks the beginning of scientific leprology.1

Leprosy is an ancient disease; sacred writings from India in the sixth century bc give a good description of a similar or identical illness. By the second century ad, Greek physicians in Europe wrote descriptions of the disease, evidently well established by that time. Stigmatization of patients with leprosy remains an unfortunate but enduring legacy of the European pandemic that occurred from 1,000–1,500 ad Hansen’s attribution of Mycobacterium leprae as its etiologic agent in 1873 marks the beginning of scientific leprology.1

![]() Effective chemotherapy began with the introduction of sulfones in 1943. In 1961, the limited growth of M. leprae in the mouse footpad provided a way to screen for therapeutic agents and to identify drug resistance.2 In 1970, rifampin was the first drug to be identified as bactericidal for M. leprae and is now the cornerstone of most therapeutic regimens. Ridley and his associates3 provided a detailed account of the granulomatous spectrum of leprosy that is useful to clinicians and pathologists and essential to subsequent immunologic studies. Jopling clearly defined and separated the two common reactional states.

Effective chemotherapy began with the introduction of sulfones in 1943. In 1961, the limited growth of M. leprae in the mouse footpad provided a way to screen for therapeutic agents and to identify drug resistance.2 In 1970, rifampin was the first drug to be identified as bactericidal for M. leprae and is now the cornerstone of most therapeutic regimens. Ridley and his associates3 provided a detailed account of the granulomatous spectrum of leprosy that is useful to clinicians and pathologists and essential to subsequent immunologic studies. Jopling clearly defined and separated the two common reactional states.

![]() In 1919, the lepromin skin test inaugurated systematic study of host resistance as the source of disease diversity,4 with lymphocyte transformation tests being established in the 1960s as an in vitro correlate. The recognition of leprosy in the nine-banded armadillo, in 1971, provided a source of large quantities of highly purified M. leprae for a wide variety of investigations,5 culminating in the sequencing of the entire genome of M. leprae in 2001.6

In 1919, the lepromin skin test inaugurated systematic study of host resistance as the source of disease diversity,4 with lymphocyte transformation tests being established in the 1960s as an in vitro correlate. The recognition of leprosy in the nine-banded armadillo, in 1971, provided a source of large quantities of highly purified M. leprae for a wide variety of investigations,5 culminating in the sequencing of the entire genome of M. leprae in 2001.6

Epidemiology

![]() Now primarily a disease of developing countries, leprosy is endemic in all continents, except Antarctica. In the Americas, only Canada and Chile are not endemic countries, with Texas and Louisiana having endemic foci in the United States. The southern-most nations of Europe have a very low incidence, while leprosy is endemic in many Pacific islands. The Indian subcontinent has two-thirds of the world’s leprosy burden. The highest case detection rates are in Angola, Brazil, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Madagascar, Nepal, and Tanzania.7,8 During the decade of the 1990s, the prevalence of leprosy fell by 90%, because patients completing a course of multiple-drug therapy have been considered cured, but the incidence of the disease, which varies in direct proportion to case finding efforts, has not been convincingly reduced.

Now primarily a disease of developing countries, leprosy is endemic in all continents, except Antarctica. In the Americas, only Canada and Chile are not endemic countries, with Texas and Louisiana having endemic foci in the United States. The southern-most nations of Europe have a very low incidence, while leprosy is endemic in many Pacific islands. The Indian subcontinent has two-thirds of the world’s leprosy burden. The highest case detection rates are in Angola, Brazil, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Madagascar, Nepal, and Tanzania.7,8 During the decade of the 1990s, the prevalence of leprosy fell by 90%, because patients completing a course of multiple-drug therapy have been considered cured, but the incidence of the disease, which varies in direct proportion to case finding efforts, has not been convincingly reduced.

![]() In all populations studied, lepromatous disease is more common in men than in women by a 2:1 ratio.9 If leprosy is common, the high resistance forms (tuberculoid—TT and borderline tuberculoid—BT) dominate. If leprosy is uncommon, the low resistance forms (borderline lepromatous—BL and lepromatous—LL) dominate. Leprosy is said to be a disease of rural incidence but of urban prevalence. The median age of onset is less in tuberculoid than in lepromatous patients, but in both groups, leprosy is predominantly a young person’s disease, the medial age of onset being less than 35 years. However, age is not protective; new cases of each type occur in the eighth and ninth decades of life. The incubation time for tuberculoid leprosy (TT) is up to 5 years and for lepromatous may be 20 years or longer.

In all populations studied, lepromatous disease is more common in men than in women by a 2:1 ratio.9 If leprosy is common, the high resistance forms (tuberculoid—TT and borderline tuberculoid—BT) dominate. If leprosy is uncommon, the low resistance forms (borderline lepromatous—BL and lepromatous—LL) dominate. Leprosy is said to be a disease of rural incidence but of urban prevalence. The median age of onset is less in tuberculoid than in lepromatous patients, but in both groups, leprosy is predominantly a young person’s disease, the medial age of onset being less than 35 years. However, age is not protective; new cases of each type occur in the eighth and ninth decades of life. The incubation time for tuberculoid leprosy (TT) is up to 5 years and for lepromatous may be 20 years or longer.

![]() The preponderance of opinion supports the traditional view that M. leprae is transmitted from human-to-human, but the presence of a lepromatous-like illness caused by M. leprae in wild armadillos,10 evidence of armadillo exposure as a risk factor for leprosy in people,11 and the presence of an M. leprae-like organism on sphagnum moss,12 suggest that nonhuman sources for M. leprae may be important. The route of infection is unproven, but current evidence favors respiratory transmission; evidence for congenital and percutaneous transmission has been presented, but these are probably rare.13 In leprosy endemic areas, subclinical infection is common, as judged by serologic studies identifying M. leprae-specific antibodies,14 but the incidence of overt disease is by comparison very small, most individuals apparently making a curative immunological response.

The preponderance of opinion supports the traditional view that M. leprae is transmitted from human-to-human, but the presence of a lepromatous-like illness caused by M. leprae in wild armadillos,10 evidence of armadillo exposure as a risk factor for leprosy in people,11 and the presence of an M. leprae-like organism on sphagnum moss,12 suggest that nonhuman sources for M. leprae may be important. The route of infection is unproven, but current evidence favors respiratory transmission; evidence for congenital and percutaneous transmission has been presented, but these are probably rare.13 In leprosy endemic areas, subclinical infection is common, as judged by serologic studies identifying M. leprae-specific antibodies,14 but the incidence of overt disease is by comparison very small, most individuals apparently making a curative immunological response.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Risk factors are birth or residence in a known endemic area, a family member with leprosy, reflecting common genetic susceptibility, environmental exposure, or both, and, as with many other infections, poverty. Therapeutic use of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies and the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) have been associated with the onset of leprosy.15,16

Mycobacterium leprae, the cause of leprosy, is a noncultivable, Gram-positive, obligate intracellular, acid-fast bacillus. Sequencing of the bacillary genome17 revealed gene deletion and decay leaving M. leprae with few respiratory enzymes, providing an explanation for the failure to cultivate the organism in cell-free media, as well as for its obligatory intracellular environment. In tissues or smears, M. leprae is quantified by the biopsy index (BI), a logarithmic scale as to the numbers of bacilli per oil immersion field (OIF): a BI of 6 is 1,000 or more bacilli/OIF; a BI of 5 is 100–1,000/OIF; a BI of 4 is 10–100/OIF; a BI of 3 is 1–10/OIF; a BI of 2 is 1 bacillus/1–10 OIFs; a BI of 1 is 1 bacillus/10–100 OIFs; and a BI of 0 is no bacilli in 100 OIFs. Because a BI of 6 indicates 109 bacilli per gram of granuloma, tissue with a BI of 0, may have as many as 103 organisms per gram.

The bacillary cell wall consists of a peptidoglycan backbone linked to arabinogalactan and mycolic acids. Immunogenic proteins are associated with the cell wall, and also are present in the cytoplasm. The cell-wall-associated lipoproteins, ligands for pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLR2 and NOD2 of the innate immune system, probably initiate the host’s first response M. leprae. This response may be important in determining the eventual clinical outcome.18 A lipoglycan target of both antibody and cellular immune responses, lipoarabinomannan, courses through the outer membrane and inserts into the cell membrane. Phenolic glycolipid I is a major, species specific and immunogenic constituent of the highly nonpolar outer layer of the bacillus. Entry into nerves is mediated by the binding of the species-specific trisaccharide in phenolic glycolipid I to laminin-2 in the basal lamina of Schwann cell–axon units,19 providing a rationale for why M. leprae is the only bacterium known to invade peripheral nerves.

A twin study has provided compelling evidence that both genetic and environmental factors are important in determining disease susceptibility and expression.20 A region on chromosome 10p13, including the PARK2 and PACRG, loci for susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease, has been found to also contain a risk factor for the development of leprosy.21 This includes both tuberculoid and lepromatous forms, and has been identified in a number of genetically diverse populations, but not all. Major histocompatibility complex class II antigens appear to influence the clinical presentation, but not disease susceptibility,22 while PRRs such as the TLRs and NOD2 may influence both.23–27 The great majority of people exposed to M. leprae are presumed to make a curative immunologic response, while the clinical presentation of the granulomatous spectrum of leprosy provides an immunologic spectrum of host defense, thus providing an exemplary model for examining cell-mediated immunity (CMI) in humans.

Clinical Findings

For physicians practicing in nonendemic areas, learning that the patient has risk factors for leprosy, i.e., birth or residence in an endemic area, or a blood relative with leprosy may lead to a correct diagnosis of leprosy.

Historic data or symptoms that should elicit further suspicion of leprosy include complaints referable to peripheral neuropathy, persistent nasal stuffiness, ocular symptoms, and, in young men, loss of sexual drive or infertility.

Ridley and his associates provided the most detailed description of the granulomatous spectrum of leprosy,28,29 integrating both clinical and histologic changes. Ridley’s construct is a six-member spectrum, ranging from high to low resistance, TT (polar tuberculoid), BT (borderline tuberculoid), BB (borderline), BL (borderline lepromatous), LLs (subpolar lepromatous), and, finally, LLp (polar lepromatous):

Conceptually, TT and LLp are clinically stable, but, between the poles, the host response may change, as indicated by the arrows, upgrading (or reversing) to a state of higher resistance, often with devastating inflammation, or downgrading to a posture of lower resistance, usually silent but occasionally inflammatory. BT patients may upgrade to TT, thus, becoming stable, but LLs patients do not downgrade to LLp nor do LLp patients upgrade. (“LL” includes both LLs and LLp patients.) The host’s granulomatous response is the result of the degree of CMI directed against M. leprae. The classification is determined primarily by clinical and histologic changes, bacillary numbers being a secondary consideration. Patients along the clinical spectrum of leprosy are presumed to be manifestations of evolving immune responses, which, based on environmental and genetic factors, will eventually gravitate toward one of the two poles.

In comparison of pre-Ridley and Ridley terminology, “tuberculoid” corresponds to TT and BT, “borderline” or “dimorphic” to BB and BL, and “lepromatous” to LLs and LLp. In virtually all TT patients, and in most BT cases, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cannot be found, whereas in BB, BL, LLs, and LLp, bacilli are demonstrable with ease. Ridley’s construct is useful in classifying patients, especially for immunity.

Five types of peripheral nerve abnormalities are common in leprosy. (1) Nerve enlargement (usually perceived as asymmetry), particularly in those close to the skin, generally thought to be due to the fact that those locations are coolest in temperature, such as the great auricular, ulnar, radial cutaneous, superficial peroneal, sural, and posterior tibial. (2) Sensory impairment in skin lesions. (3) Nerve trunk palsies either with signs and symptoms of inflammation or without such overt manifestations, that is, silent neuropathy,30 usually with both sensory and motor loss (weakness and/or atrophy) and, if long standing, also with contracture. (4) Stocking-glove pattern of sensory impairment (S-GPSI), with a slow loss of type C fibers, involving heat and cold discrimination before loss of pain or light touch, beginning in acral areas and, over time, extending centrally but initially sparing the palms. (5) Anhidrosis on palms or soles suggests sympathetic nerve involvement.

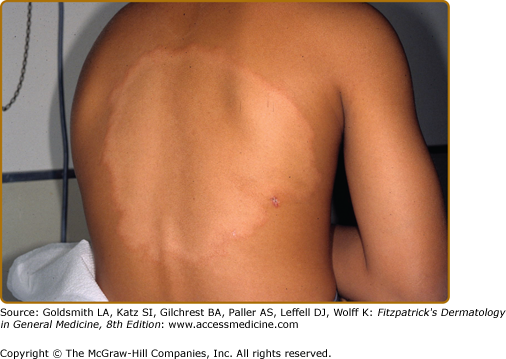

In TT leprosy immunity is strong as manifested by spontaneous cure and the absence of downgrading to a posture of less host resistance. The primary skin lesion of TT is a sharply marginated plaque, often annular secondary to peripheral propagation and central clearing. Typically, the lesion is firmly indurated, elevated, erythematous, scaly, dry, hairless, and hypopigmented (Fig. 186-1), but clinically, considerable variation is encountered (eFig. 186-1.1).

Figure 186-1

A solitary, anesthetic, and annular lesion of polar tuberculoid leprosy (TT), which had been present for 3 months. Its sharp margins, erythema, and scale are more evident than its elevation. The central red dots are the sequelae or “footprints” of testing for pinprick perception when it is absent. (If present, the patient withdraws, preventing overly purpuric consequences.) The central portion of the lesion was slightly hypopigmented as compared to the surrounding normal skin.

eFigure 186-1.1

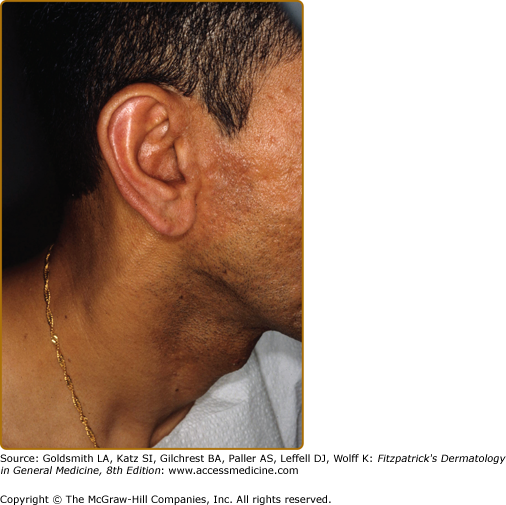

The right ear had become erythematous, as compared to the left. Anterior to the red ear is a slightly indurated, erythematous plaque. What could be interpreted as a neck vein is an enlarged great auricular nerve. The patient was classified as TT because of the histologic finding of caseation necrosis in a tuberculoid granuloma, see eFig. 186-8.1.

A nearby sensory nerve may or may not be enlarged (eFig. 186-1.1), but the lesion itself is characteristically anesthetic and anhidrotic. Skin lesions are often solitary, particularly in those patients who are TT de novo, as contrasted to those who upgrade to TT from BT, where multiple lesions, usually no more than three, may be found. In both groups, immunity is sufficient to affect cure, thus, placing an upper limit of 10 cm on lesion size, but antibiotic therapy is recommended.

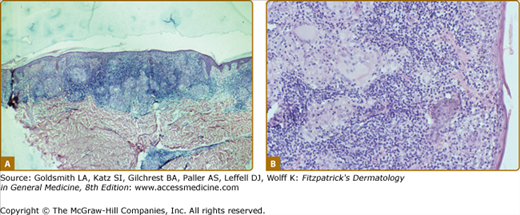

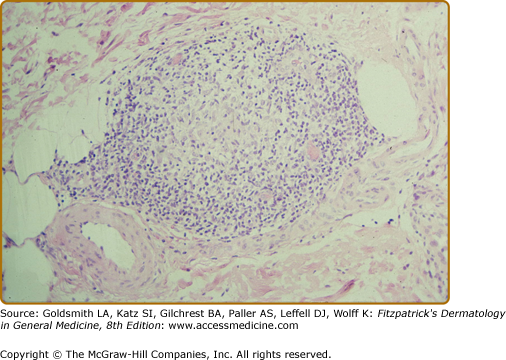

In de novo TT lesions, small, well-developed epithelioid tubercles are surrounded by large lymphocytic mantles, but are uncommonly seen. In TT upgrading from BT, abundant Langhans-type giant cells and a brisk exocytosis into the epidermis are usually found in addition to the lymphocytic mantle (Fig. 186-2). Rarely caseation necrosis is seen, and, if present, warrants the classification of TT (eFig. 186-2.1). AFB are not found.

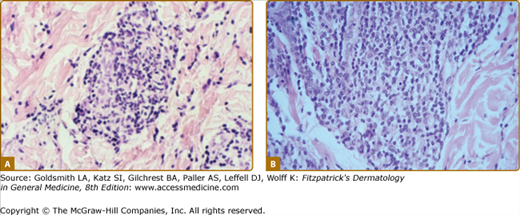

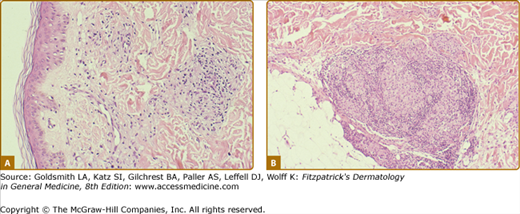

Figure 186-2

Two views of the histology of a TT lesion. A. The lower power view looks a lot like that of lupus vulgaris, which is the origin of the term “tuberculoid” leprosy. (H&E, 10× objective.) B. The high-power view of the same lesion shows abundant Langhan’s giant cells, epithelioid tubercles, a dense lymphocytic infiltrate and a brisk exocytosis into the epidermis. (H&E, 20× objective.)

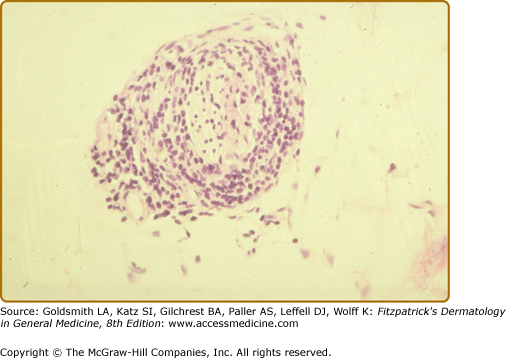

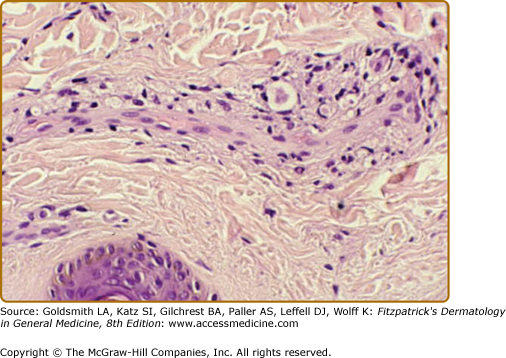

eFigure 186-2.1

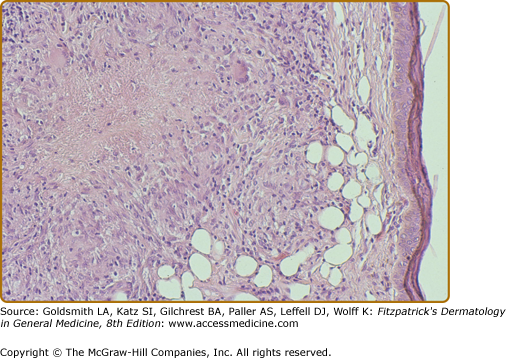

The histology of the biopsy specimen taken for the TT lesion shown in eFig. 186-1.1. The skin anterior to the ear was only slightly indurated, but the presence of caseation necrosis required the classification of TT. (H&E, 20× objective.)

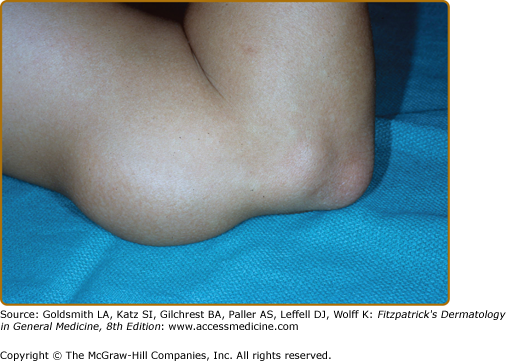

In BT disease (Fig. 186-3 and eFigs. 186-3.1 and 186-3.2), immunologic resistance is strong enough to restrain the infection, in that the disease is limited and bacillary growth retarded, but the host response is insufficient to self-cure. These patients are somewhat unstable—resistance may increase, upgrading to TT, or decrease, downgrading to BL.

Figure 186-3

One of several lesions of borderline tuberculoid leprosy (BT), which had an incompletely annular configuration with satellite papules. Compared to the TT lesion in Fig. 186-1, there is less erythema, no evident scales, but the sharp margination, and the “footprints” of absent pinprick perception are well developed. The lesional histology is shown in eFig. 186-3.2.

eFigure 186-3.1

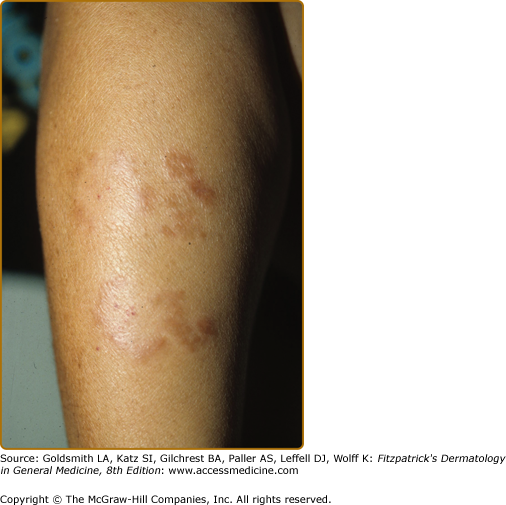

A large annular BT lesion present for 7 years, beginning near the midline, and expanding slowly by peripheral extension and central clearing. The uniform hypopigmentation within the annulus returned to normal slowly, taking about 5 years. The lesional histology is shown in eFig. 186-8.3.

The primary skin lesions of BT are plaques and papules (Box 186-1). As in TT, an annular configuration is common and both borders are sharply marginated but annular lesions or plaques may have sharply marginated satellite papules (Fig. 186-3). Hypopigmentation may be conspicuous in darkly pigmented patients (eFig. 186-3.1). In contrast to TT, typically, there is little or no scaling, less erythema, less induration, and less elevation, but lesions may become much larger, that is, well over 10 cm in diameter, a single lesion sometimes involving an entire extremity over time (eFig. 186-3.1). Multiple, asymmetric lesions are the rule, but solitary lesions are not rare. Impairment of sensation in skin lesions is the rule and nerve trunk involvement, enlargement or palsies, usually in no more than two and asymmetric, are common. Nerve abscesses, when they occur, are most often seen in males with BT disease (eFig. 186-3.2).

PRIMARY LESIONS

|

SECONDARY LESIONS

|

CLINICAL CONSTELLATIONS

|

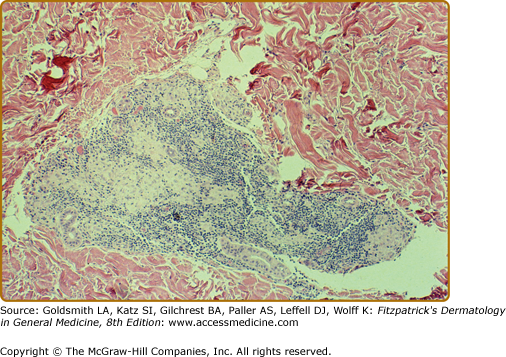

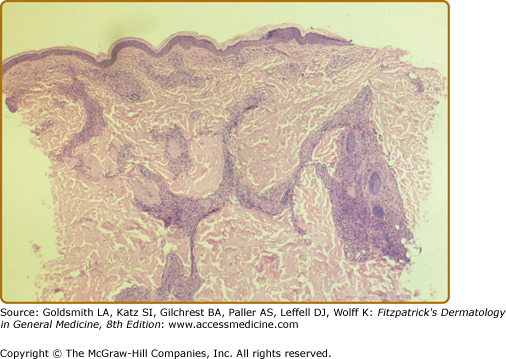

In BT tissues, well-organized epithelioid tubercles are present but the lymphocytic mantles are less well developed than in TT disease (eFigs. 186-3.3 and 186-3.4). Also, Langhans-type giant cells are inconstant. Epidermal exocytosis, if present at all, is focal. AFB are only rarely seen in BT. The presence of AFB or plasma cells in what otherwise appears to be BT warrants consideration of a reversal reaction.

eFigure 186-3.3

The histology of the biopsy specimen taken from the BT lesion shown in Fig. 186-2. An epithelioid tubercle without any giant cells is surrounded by a lymphocytic mantle. (H&E, 20× objective.)

eFigure 186-3.4

The histology of the biopsy specimen taken from the BT lesion shown in eFig. 186-2.1. The granulomatous pattern is not as tidy as in eFig. 186-8.2, but the critical elements are present, i.e., epithelioid tubercles and lymphocytic mantles, even if they are they incomplete. (H&E, 10× objective.)

BB is the immunologic midpoint or midzone of the granulomatous spectrum, being its most unstable area, with patients quickly up- or downgrading to a more stable granulomatous posture with or without a clinical reaction. Characteristic skin changes are said to be annular lesions with sharply marginated interior and exterior margins, large plaques with islands of clinically normal skin within the plaque, giving a “Swiss cheese” appearance, or the classic dimorphic lesion. Because of instability, the BB posture is short lived and such patients are rarely seen. For example, we have yet to see a nonreactional patient meeting both clinical and histologic criteria.

In BB, the epithelioid differentiation remains, but lymphocytes are sparse, giant cells are absent, and bacilli are easily found.

In BL disease, resistance is too low to significantly restrain bacillary proliferation, but still sufficient to induce tissue destructive inflammation, especially in nerves. Thus, BL patients have the worst of both worlds. The BL category is highly variable in its clinical expression (eFigs. 186-3.5 and Fig. 186-4). Although seen in only a third of BL patients, the classic dimorphic lesion is the most characteristic, having an annular configuration with a poorly marginated outer border (lepromatous like) but a sharply marginated inner one (tuberculoid like), hence, having both morphologies thus “dimorphic leprosy.” Variation may be considerable in one patient and even greater across the entire BL population. Poorly or sharply marginated plaques with “punched out” or “Swiss cheese” sharply marginated areas of normal skin in the interior of the plaque are also characteristic, and can be thought of as a variant of the classic dimorphic lesion (eFig. 186-3.5). Annular lesions with sharply marginated exterior and interior borders are not uncommon. Lepromatous-like, poorly defined papules and nodules may be numerous, but are usually accompanied by sharply marginated lesions somewhere.

Lesions range in number from solitary to numerous and widespread. Generally, the annular and plaque lesions are asymmetrically distributed, but the lepromatous-like nodules, if numerous, are symmetric (Fig. 186-4). Skin lesions are often hypesthetic or anesthetic, but not necessarily so. Nerve trunk palsies have their highest prevalence in BL disease, but are variable in number, ranging from none to serious neurologic deficits, both motor and sensory, in all four extremities. Involvement of both median and ulnar nerves, not infrequently bilateral, is characteristic. When disease is extensive, BL patients may also develop S-GPSI.

Untreated BL patients have slow relentless progression of skin and nerve changes. With or without treatment, this course may be altered by a reactional state (see section below), upgrading or reversal reactions being more common than erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). Also, BL patients may silently downgrade to an LLs granulomatous posture.

One classic BL dermal response is a relatively dense lymphocytic infiltrate restricted to the space occupied by the macrophages (eFig. 186-4.1). The macrophages are often foamy, but undifferentiated macrophages may be common. The epidermis is undisturbed. In nerves, the other classic BL response is lamination of the perineurium with infiltration by inflammatory cells (eFig. 186-4.2). In BL, as contrasted to LLs, the inflammatory infiltrate is so dense as to obscure the lamination. An alternative BL pattern is that of a chronic lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (eFigs. 186-4.3 and 186-4.4A). Plasma cells may be present. Bacilli are easily found, and globi are not unusual.

eFigure 186-4.1

The classic histology of a BL dermal lesion. A. The lymphocytic infiltrate is restricted to the space occupied by the macrophages in this small lesion. (H&E, 40× objective.) B. A larger BL dermal lesion with an even denser infiltrate, further emphasizing the restriction of the lymphocytes to the space occupied by the macrophages. (H&E, 40× objective.) Both are in contrast to TT and BT lesions where the lymphocytes extend into the tissues surrounding the epithelioid tubercles.

eFigure 186-4.3

This low-power photomicrograph of a BL lesion shows two changes each of which gives good reason to consider the possibility of leprosy. The superficial and deep infiltration is the most common but the least specific of the two. The bizarre, sausage-shape configuration of the infiltrate is very suggestive of leprosy, but is not a common finding. The third “suggestive” finding is that of apparently normal skin. (Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 10× objective)

eFigure 186-4.4

A. From a BL lesion before treatment, showing a pattern of chronic inflammation showing edema modifying tissue architecture. (H&E, 20× objective.) B. From the same patient 4 weeks later and 1 week into a DTH reaction, showing epithelioid differentiation of macrophages, tubercle formation, foci of more lymphocytes, and lymphocytes in “mantle” distribution. (H&E, 20× objective.)

In lepromatous leprosy (LL) the diminished CMI toward M. leprae permits unrestricted bacillary replication and widely disseminated, multiorgan disease. Diffuse dermal infiltration is always present subclinically and, may be overtly manifested by enlargement of ear lobes, widening of the nasal root, fusiform swelling of the fingers, and the skin being thrown into folds. Poorly defined nodules are the most common lesions, usually up to 2 cm in diameter, and are symmetrically distributed. A conjunction of skin folding and nodule formation produces the “leonine faces.”

Dermatofibroma-like or histiocytoma-like lesions, usually multiple, are sharply marginated erythematous papules or nodules, sometimes confluent into plaques (Fig. 186-5A and 186-5B). These were first identified in relapsing patients as “histoid” leprosy, but are not unusual as presenting lesions. Less common presenting skin lesions include digitate, barely indurated patches of erythema (Fig. 186-6), which in light-skinned patients are sometimes followed by a mild hyperpigmentation, a veil of melanin concealing the erythema; in dark-skinned patients multiple hypopigmented macules may be seen. Also, rarely, a dense dermal infiltrate may mimic a nevoid lesion (see eFig. 186-6.1).

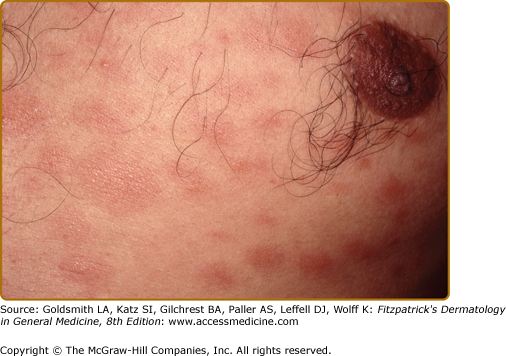

Figure 186-5

A. Multiple dermatofibroma-like papules, with some confluence to form plaques. B. Multiple dermatofibroma-like and histiocytoma-like lesions in a patient who had sought no help for these, until taken to the hospital from an automobile accident. The senior pathologist who reviewed the case suggested a Fite stain. The skin between such nodules is diffusely infiltrated.

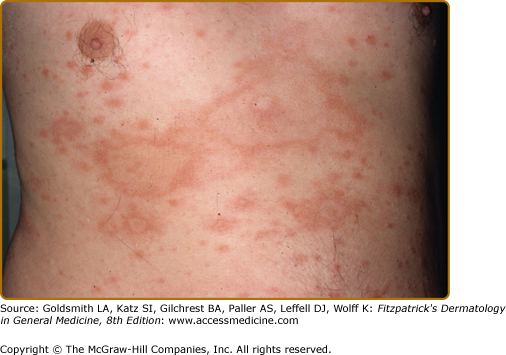

Figure 186-6

These multiple, barely palpable, erythematous, and asymptomatic lesions had been erupting over the previous 2 months in an LLs patient. With treatment, as the lesions remitted they became mildly hyperpigmented. Here, the accentuation of the normal skin markings is in contrast to their effacement, as shown in Fig. 186-4.

A clinical clue of LLs is a sharply marginated region in a lesion, perhaps the residual of a BL lesion in a patient who has downgraded to LLs, or the presence of dermatofibroma-like lesions. The distinction between LLs and LLp is usually made histopathologically.

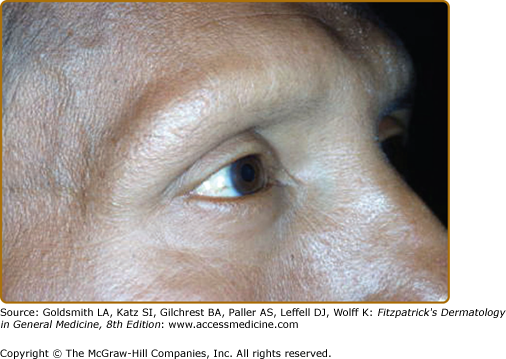

Hair loss is most common in the eyebrows (eFig. 186-6.2), where it may progress medially to laterally or be patchy. Hair loss may also occur on the eyelashes and extremities, and may be partially reversible if treated early. Scalp involvement is rare. Loss of eccrine sweating from sympathetic nerve involvement is common, as manifested by dry palms or soles. Any given skin lesion may or may not be hypoesthetic but generally, in each patient, some are. Nerve trunk palsies occur, but are less common than in BL. The stocking glove pattern of sensory impairment is common and may be so severe as to lead to debilitating trophic changes of the hands or feet.

Untreated LL disease is relentlessly progressive, but this course may be altered by reactional states. LLs and LLp subjects frequently develop erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). LLp patients do not develop reversal reactions (see below), whereas LLs patients may.

LLs and LLp have many histologic features in common. (1) Nodular lesions, consisting mainly of foamy or undifferentiated macrophages, have replaced much of the dermis, with loss of appendages. The epidermis is attenuated by the nodule, but a thin layer of dermis (grenz zone) separates the two and a Fite stain shows numerous bacilli. (2) Clinically normal skin will show a variably dense infiltrate of foamy or undifferentiated macrophages, often scant in a perivascular and periappendageal distribution, but the epidermis is undisturbed (eFig. 186-6.3). (3) Both LLs and LLp may show small but dense aggregates of lymphocytes, which may be B-cells. (4) The appearance of the macrophages varies with the age of the lesion, ranging from undifferentiated to foamy cells (eFigs. 186-6.4 and 186-6.5). (5) Endothelial AFB are not uncommon in LLs and LLp. (6) Plasma cells and mast cells, the latter often easily identified by the AFB counter stain, are sometimes increased. (7) In older lesions, foreign-body giant cells may be common, probably arising in response to the death of macrophages containing many dead AFB (eFig. 186-6.6).