Leishmaniasis and Other Protozoan Infections: Introduction

|

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis, a truly ancient disease,2 was recognized on Amerindian pottery drawings dating back to the first century ad.3 It was named after W.B. Leishman who identified organisms in smears taken from the spleen of a patient who died from “dum-dum fever” in India in 1901. The disease burden remains important in the twenty-first century with up to 2 million individuals developing systemic disease annually and accounting for around 70,000 deaths per year.4

The various types of leishmaniasis are confined primarily to the Mediterranean basin, Southern Europe, Central Africa, and parts of Southern and Central Asia [Old World (OW)], and Central and South America [New World (NW)]. The infection is endemic in 88 countries, 72 of which are developing countries.

In Western countries, the incidence is increasing due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-Leishmania coinfection, military appointment, and tourism in endemic countries.5,6 New Zealand, Antarctica, and the Pacific islands are Leishmania-free. Australia was thought to be devoid of Leishmania species until 2004, when it was discovered in red kangaroos that had developed ulcers over their limbs or ears, raising the possibility of imported species becoming endemic, or of a current still unrecognized human form of the disease.7

More than 90% of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL) cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.8 In the United States, most LCL cases are imported; however, the Southern and Central parts of Texas are considered endemic for Leishmania mexicana.9,10

The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified leishmaniasis as a category 1 disease (emerging and uncontrolled). The recent geographic spread is attributed to massive rural-urban migration and agro-industrial development projects that bring nonimmune urban residents into endemic rural areas. Other incriminated factors include natural disasters, cessation of malaria spraying leading to increased sandfly population, reconstructions, control programs, global warming, wars, and deforestation.

Risk factors for contracting the disease include residing in an endemic area and in a ground floor, the design and construction material of the house, and the presence of domesticated animals. The prevalence of the disease increases until the age of 15 then seems to stabilize, probably reflecting development of immunity.11 In general, males have greater likelihood of developing the disease. This can be explained by behavioral differences in exposure as well as by hormonal modulation of disease susceptibility or resistance.12

See Box 206-1 for various forms of leishmaniasis and their abbreviations.

|

The genus Leishmania consists of parasitic protozoa of the phylum Sarcomastigophora, order Kinetoplastida, and family Trypanosomatidae. At least 21 species are pathogenic for humans and all are essentially transmitted by the bite of an infected female phlebotomine sandfly.4 Cases of venereal14 and vertical15,16 transmission, as well as transmission from infected blood transfusion17 or needles18–22 have, however, been reported.

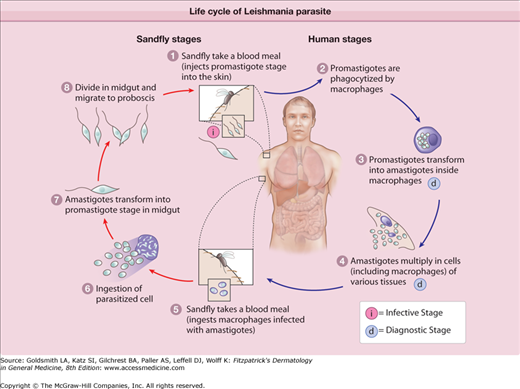

Leishmania are dimorphic parasites; in the gut of the sandfly or in culture, they exist in the spindle-shaped motile (single anterior flagellum) promastigote form (10–20 μm). In the cells of the host reticuloendothelial system, Leishmania exist in the oval nonmotile amastigote form (2–6 μm) that has a relatively large basophilic nucleus and a smaller rod-shaped kinetoplast of extranuclear DNA at the base of the lost flagellum.23 Infected macrophages are ingested by the fly during a blood meal and the amastigotes are released into the stomach of the insect where they immediately transform into the promastigote form. The latter migrate to the alimentary tract of the fly, multiply extracellularly by binary fission, and in few days, reach the esophagus and the salivary glands of the fly where they change into infective metacyclic promastigotes, which will be released into the skin at next bite. They are then phagocytosed by host macrophages where they transform into amastigotes that multiply by binary fission and get released following cellular burst to infect other macrophages (eFig. 206-0.1)

Leishmaniasis is mostly zoonotic, being incidentally transmitted to humans from wild and domestic animals (primary reservoir hosts) (Table 206-1).24,26–29 However, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) caused by Leishmania donovani and OW-cutaneous leishmaniasis (OW-CL) caused by some Leishmania tropica strains are anthroponotic diseases (i.e., humans are the primary reservoir hosts).

Leishmania Species | Vector | Main Reservoir Hosts | Disease Caused | Geographic Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Old World (OW) Leishmaniasis | |||||

OW Leishmaniasis | Leishmania major | Phlebotomus |

| LCL DCL (1 isolate in Ethiopia) |

|

Leishmania tropica |

| LCL, LR, VTL |

| ||

Leishmania aethiopica | Hyraxes | LCL, DCL, MCL (rarely) | East Africa (Kenya, Sudan, Ethiopia) | ||

Leishmania donovani | Humans, dogs | LCL, VL, PKDL | India, Sudan, Kenya, China, Pakistan, Nepal, Tanzania, | ||

New World Leishmaniasis | |||||

Leishmania mexicana complex | L. mexicana Leishmania amazonensis | Lutzomyia | Rodents Wood rat in Texas Spiny rats Less commonly: rodents, marsupials, and carnivores | LCL, DCL LCL, LR, MCL, DCL, VL | Central America, Mexico, Texas South America |

Leishmania pifanoi | Unknown | LCL | Venezuela, South America | ||

Leishmania venezuelensis | Domestic cat? | LCL | |||

L garnhami | Opossum | LCL | |||

Leishmania (Viannia) or Leishmania braziliensis complex | L. (V) braziliensis Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis L. (Viannia) peruviana L. (Viannia) Guyanensis L. (Viannia) lainsoni L. (Viannia) colombiensis | Lutzomyia Psychodopygus Lutzomyia | Rodents Less commonly: canids, felids, equines Sloths Less commonly: marsupials, rodents Domestic dogs Less commonly: humans, rodents, Marsupials Sloths Less commonly: anteaters and opossums Lowland Paca, brown capuchin monkeys Sloths Less commonly: anteaters and armadillos | LCL, MCL, LR, uta LCL, LR, MCL, DCL LCL LCL, LR, MCL (rarely) LCL LCL, VL (rarely, reported in Venezuela) | South America, Central America, Mexico Central America, Colombia, Ecuador Peruvian Andes Guyana, Brazil Brazil, Bolivia, Peru Colombia, Venezuela |

OW and NW Leishmaniasis | |||||

Leishmania chagasi/Leishmania infantum | Lutzomyia, Phlebotomus | Dog, fox, opossum, porcupine | LCL, infantile VL | Mediterranean basin; Middle East and Central Asia to Pakistan; China; Central and South America | |

The insect vector of leishmaniasis, the female phlebotomine sandfly, is grouped under the Suborder Nematocera of the order Diptera. Three genera [(1) Phlebotomus in the OW, and (2) Lutzomyia and (3) Psychodopygus in the NW], and around 70 species are implicated as vectors.31 They are widely distributed and have predilection to intertropical and warm temperate zones. Only the female sandfly is hematophagus. Phlebotomine sandflies are less than 3 mm long, and do not fly far from their breeding site. Their activity is mostly crepuscular or nocturnal while the host is asleep. They rest during the day and lay their eggs in dark, cool, humid, and organic matter-rich places such as rodent burrows, bird’s nests, and house wall fissures. Being exophilic and exophagic, they prefer to rest and to have their meal outdoors, which limits their control through house spraying.

The resulting disease depends on the fate of the phagocytosed amastigotes. This in turn is function of numerous parasite- and host-related factors, as well as other factors that may account for geographical differences.8,32

In general, parasites interfere with the signaling pathways, intracellular kinases, transcription factors, and gene expression of macrophages, compromising their ability to generate leishmanicidal substances. In addition, they impair dendritic cell activation, migration, and ability to secrete T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines.

Sandfly saliva is increasingly recognized as an essential element in the pathogenesis of the disease. Besides containing vasodilators, anticoagulants, and immunomodulators, it may also increase the inoculum size and the diameter of the lesion.34 Intraspecific variations of sandfly saliva may even affect the overall clinical outcome of Leishmania infantum-induced disease by shifting the adaptive immunity from a Th1 to a Th2 immune response. The development of anti-saliva antibodies after exposure may account for the decline with age of susceptibility to the infection in endemic areas.11

Other parasite-related factors include infectivity, pathogenicity, virulence, and tissue tropism.35–39 These differ from one species to the other. For example, lipophosphoglycan and gp63 are two important promastigote virulence factors that impair infected cells’ overall functions with the former being clearly involved in Leishmania major disease but absent in L. mexicana.11

Although viscerotropic species tend to spread to the reticuloendothelial system, they may become dermotropic as a consequence of treatment such as seen in post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL).40 Similarly, L. tropica, classically dermotropic, may cause visceral disease.41,42

Malnutrition, immunosuppression, and host genetic background influence host susceptibility as well as resistance to the disease. The output of acquired T cell immunity, which depends on the net effect of the opposing Th1 and Th2 responses, largely determines the course and the therapeutic response of the infection. A dominant Th1 response resulting in the production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and nitric oxide leads to a leishmanicidal state of macrophages, and accounts for subclinical infection or self-healing LCL and the positive Montenegro skin test (that assesses delayed-type hypersensitivity to leishmanial antigen). A dominant Th2 response accounts for progressive disease such as diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL), and is characterized by anergy to leishmanial antigen (negative Montenegro skin test). Mucosal leishmaniasis patients will have both Th1 and Th2 responses, with slight predominance of Th2 immunity, explaining persistence of the disease. To summarize, T-cell immunity would be intact in LCL, defective in DCL, and pathologically exuberant in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL). Humoral immunity seems to play little or no role in determining the course of the infection. High titers of anti-leishmanial IgG correlate more with chronic, nonhealing, and visceral disease.

The clinical spectrum includes cryptic infection, LCL, and other forms including disseminated infection [DCL, MCL, VL, VTL (viscerotropic leishmaniasis), PKDL, leishmanid].31

Both cutaneous and visceral infection can remain subclinical or manifest with mild, nonspecific, and transient symptoms.8,31,44,45

LCL constitutes 50%–75% of all incident cases. It is the mildest form of Leishmania diseases and the one that prevails in the OW.3 It can be caused by all Leishmania species. Most cases heal spontaneously within 1 year and are characterized as acute LCL. Disease lasting more than 1 year is termed chronic LCL.

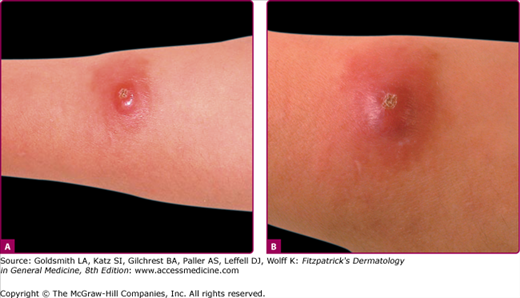

OW-CL (Aleppo boil, Baghdad boil, Oriental sore, leishmaniasis tropica, Biskra button, Delhi boil, Bouton d’orient, Lahore sore, Rose of Jericho, Kandahar sore, the little sister) is caused mainly by L. major, L. tropica, Leishmania aethiopica, and to a lesser extent L. infantum (Table 206-1).24,26–29 Two major types, (1) the moist type (caused by L. major) (Fig. 206-1) and (2) the dry type (caused by L. tropica), are identified (Table 206-2).47–50 Both types may coexist in the same patient.40

Moist Type | Dry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Synonyms | Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis | Anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

Species | Leishmania major | Leishmania tropica | |

Areas | Rural | Urban | |

Incubation Period | 2–8 weeks | Up to 8 months | |

Clinical Picture | Number of Lesions | Multiple (Up to 100 insect bite-like lesions on exposed body parts, most of them resolve and only few evolve into LCL) | Single lesion over face |

Ulceration | More prominent and early, hemorrhagic crust | Less prominent and late, serous crust | |

Period of Healing | 6 months (3–12 months) | Twice as long as moist type | |

Course/Outcome | Mild, self-limited, atrophic scars | Risk of progression to chronic LCL, Leishmaniasis recidivans or VL | |

Treatment | Observation or local treatment | Systemic treatment often required | |

L. aethiopica may cause a similar cutaneous disease to L. tropica but carries a higher risk of evolving into DCL in up to 20% of affected individuals.47 L. infantum, the causative agent of Mediterranean VL in children, may cause a self-limited skin disease in adults.51–53 Species identification cannot be made clinically and requires biochemical/molecular techniques.

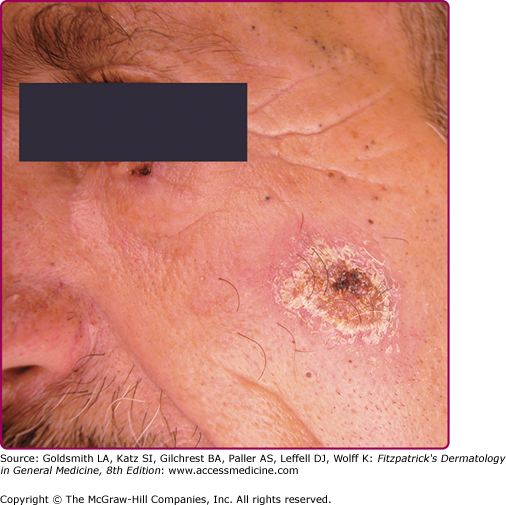

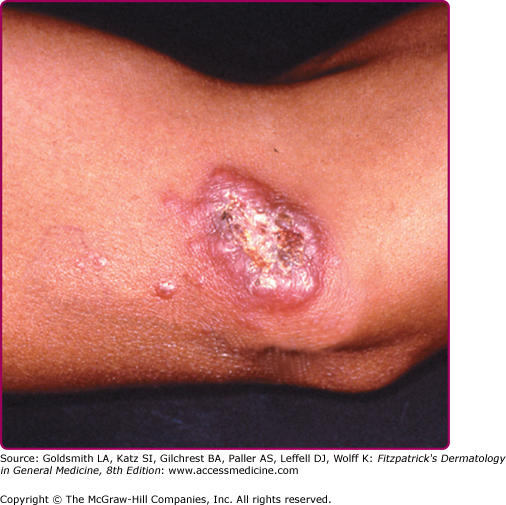

The morphologic spectrum of OW-LCL is wide. Lesions start as erythematous papules that enlarge over few weeks to form nodules/plaques and often ulcerate and become crusted (Figs. 206-2, 206-3, and 206-4; eFigs. 206-4.1 and 206-4.2). The “volcanic” noduloulcerative morphology is characteristic and consists of painless crateriform ulcer with a rolled margin and a necrotic base that is often covered with an adherent crust (Fig. 206-5). Other presentations include “iceberg nodules,”54 and eczematoid, psoriasiform,50 erysipeloid,55,56 zosteriform, paronychial, chancriform, annular, palmoplantar,57 verrucous, and keloidal58 lesions. Satellitosis (Fig. 206-6), regional lymphadenopathy, localized lymphadenitis,59 sporotrichoid lymphatic spread (eFig. 206-6.1), subcutaneous lymphatic nodules,54,60 and localized hypoesthesia61 may occur. Mature lesions may be elongated and oriented parallel to skin creases.54 Secondary bacterial infection is common.62

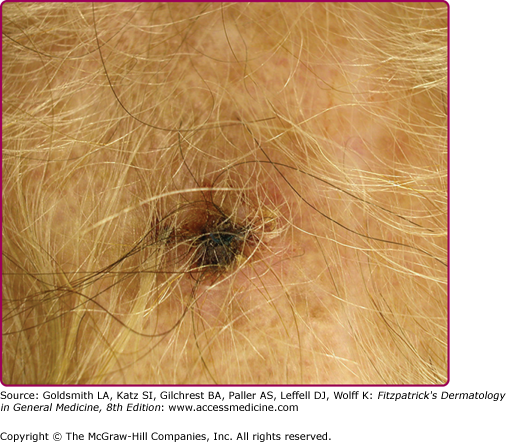

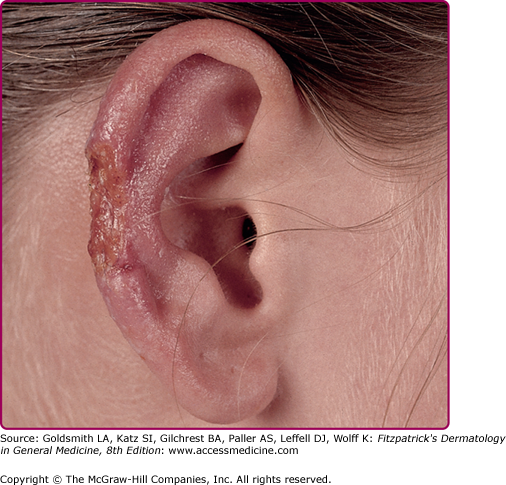

NW-LCL (valley sickness, Andean sickness, white leprosy, chiclero ulcer, uta, pian bois, and bay sore) is caused by L. mexicana and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis complexes mainly (Table 206-1). Infection with L. mexicana or Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis causes only cutaneous disease in contrast to infection with L. (V) braziliensis and Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis, which may, in 40%–80% of the cases, progress to MCL. Pure cutaneous disease is very similar to OW-LCL and isolated ulcers in exposed areas are the most common presentations. The progression of the lesions gives rise to a characteristic scar consisting of thin pale skin at the ulcer site with a hyperpigmented border.3 About 50% of the lesions caused by L. mexicana heal within 3 months, whereas those caused by L. braziliensis persist much longer and are often associated with lymphadenopathy.63,64 L. mexicana, however, is the causative organism of chiclero ulcer, a chronic mutilating infection of the pinna of the ear of forest workers in Mexico and Central America. (Fig. 206-7) Lutzomyia flaviscutellata is the major vector. In Brazil, the lower limbs are commonly affected, causing the typical Bauru ulcers.3 Uta, the Andean cutaneous form of leishmaniasis, is caused by L. braziliensis and predominantly affects exposed areas in children. Its principal vector is Lutzomyia peruensis. An atypical nodular form of NW-CL caused by Leishmania d. chagasi has been reported from Honduras65,66 and Nicaragua.67 Unusual clinical pictures have been reported, especially in immunosuppressed patients.3,68

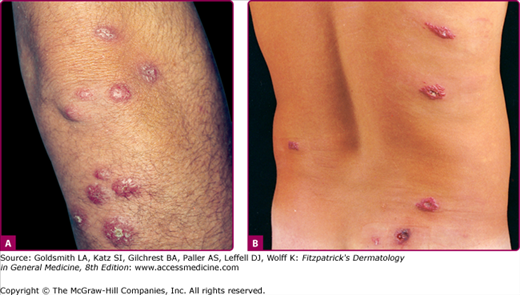

Common complications include permanent scarring, disfigurement, and social stigma. Autoinoculation or koebnerization following trauma, tattooing, or surgery have been reported.69 Major complications of LCL include chronic LCL, DCL, and MCL (in NW-LCL). Acute immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and other immunosuppressive conditions increase the risk of mucocutaneous and visceral dissemination,70–73 and of recurrence following therapy.74 Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis, defined as more than ten pleomorphic lesions in noncontiguous areas of the body, has been reported in increasing frequency to complicate NW-LCL and HIV-associated OW-LCL.69

Typically, the lesions evolve from papules to chronic disfiguring indurated nodules/plaques that are larger than average acute LCL lesions and may exhibit variable degrees of scaling, ulceration, verrucosity, and scarring. (Fig. 206-8) The diagnosis may be challenging because of the paucity of organisms seen on histologic examination.

Leishmaniasis recidivans (LR) is a rare form of chronic LCL and accounts for 3%–10% of all LCL cases. It is caused mostly by L. tropica in the OW, and less commonly by L. (V) braziliensis in the NW as well as Leishmaniasis amazonensis, L. (V) panamensis, and L. (V) guyanensis. Erythematous scaly papules, often with apple jelly appearance, at the borders of a completely or partially healed CL lesion, are characteristic. It may complicate vaccination with a live strain of Leishmania75 and usually occurs in the setting of hyperactive T-cell immunity and low antibody titers. Reactivation of dormant infection (up to 15 years after apparent resolution) after an unknown stimulus such as trauma or topical corticosteroids, rather than reinfection with different strains, is believed to account for most of the cases. In fact, several studies have demonstrated persistence of the intracellular living organisms in “healed” Leishmania lesions, this being more likely to occur if therapy was incomplete or deficient.76,77

Lupoid leishmaniasis shares similar etiology and clinical picture with LR; however, the former is not a recurrent lesion.62 The lesion characteristically occurs over the face and may resemble clinically lupus vulgaris or discoid lupus erythematosus.78 In the absence of molecular identification of parasites, the diagnosis may be delayed for several years leading to mutilation (Fig. 206-9).79

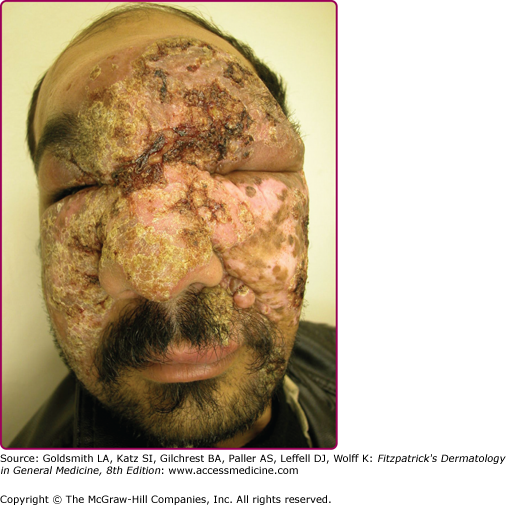

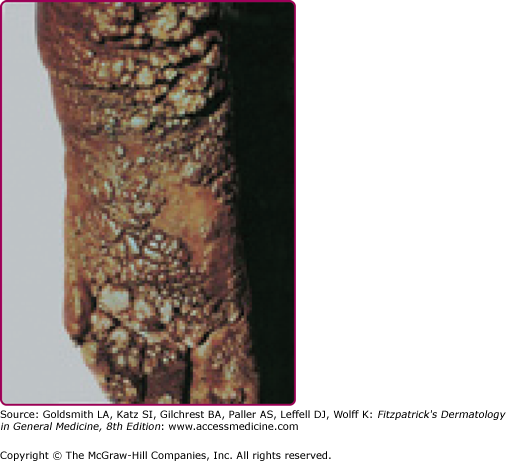

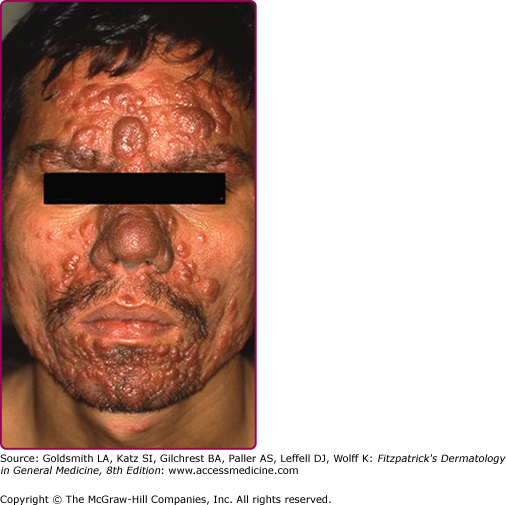

DCL, also called pseudolepromatous leishmaniasis, is an anergic rare form of cutaneous leishmaniasis that occurs in the setting of deficient cell-mediated immunity and mimics clinically and histologically lepromatous leprosy. It is usually caused by L. aethiopica in the OW and by L. amazonensis and L. mexicana in the NW. Immunosuppressed patients, especially HIV-infected individuals, may develop a severe form of DCL (>200 lesions) with no species-specific relation.4,80,81 Following a classical LCL lesion, dissemination occurs (immediately in 30% of cases but up to 11 years in others)47 in the form of nonulcerated and parasite-laden nodules (eFig. 206-9.1) with predilection for exposed areas of the body such as the face, where lesions may coalesce leading to leonine facies. Viscera are not involved. A progressive/chronic course with relapse after therapy is classical.

MCL may complicate up to 10% of LCL patients and is characterized by the chronic and progressive spread of lesions to the nasal, pharyngeal, and buccal mucosa; lesions appear 1–5 years after resolution of the primary lesion(s), or less commonly while they are still present. It is often a complication of NW-LCL caused by L. (V) braziliensis, L. (V) panamensis, L. amazonensis, and L. (V) guyanensis. Ninety percent of cases occur in Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru.82 In the OW, similar mucosal lesions caused by L. aethiopica may be seen but have a better prognosis.4,83,84

MCL results from direct extension or hematogenous/lymphatic spread to the upper respiratory tract, and rarely ocular and genital mucosa, and liver.40 Bony structures are usually spared. Stuffy nose, epistaxis, coryza, hyperemia, and nasal septum crusting and ulceration are frequent presenting symptoms and signs. If untreated, the disease evolves into either septal perforation with resulting collapse of the nasal bridge and free hanging nose (tapir nose or parrot beak) or partial/total naso-oropharyngeal mutilating ulceration (espundia) (Fig. 206-10). In rare cases, the lips, cheeks, soft palate, or larynx are involved.11 Lymphadenopathy is common in L. braziliensis-induced disease and may be associated with hepatomegaly and systemic symptoms.4

The major causes of mortality are secondary infection, pharyngeal obstruction, and respiratory failure. Cure rates decrease with advanced disease.4

VL (Sikari disease, Burdwan fever, Shahib’s disease, tropical splenomegaly, kala-azar, death fever, dum-dum fever) is endemic in the tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Ninety percent of cases occur in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Brazil, and Sudan.82 The causative agents are L. donovani and L. chagasi/infantum and to a lesser extent L. amazonensis, and Leishmania (Viannia) colombiensis. Infection with L. donovani occurs in the OW (India and Sudan), is anthroponotic and highly endemic, and involves Phlebotomus argentipes as a vector. Other infections are zoonotic and dogs are the major reservoir hosts. L. infantum afflicts mainly malnourished children in China, Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean basin.

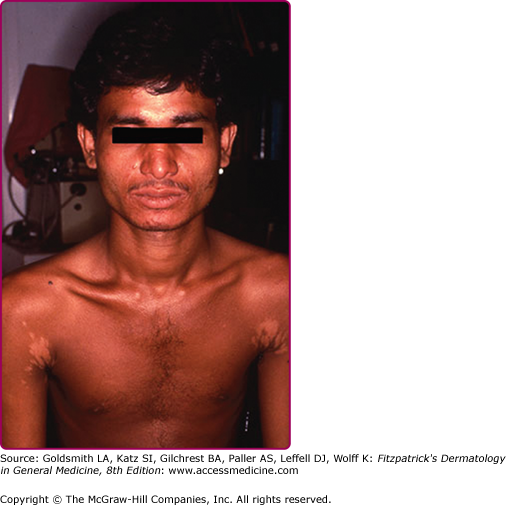

Hematogenous dissemination of the parasite to the reticuloendothelial system follows skin inoculation. However, congenital (transplacental) transmission may occur.16 Most infections remain subclinical. The incubation period and the duration of the disease are variable. The cardinal features of VL are persistent high undulating fever, leucopenia, anemia, splenomegaly, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Other findings include emaciation, burning feet (peripheral neuropathy), hepato-gastrointestinal disturbances, epistaxis, thrombocytopenia, and lymphadenopathy. Skin lesions develop later in the course of the disease and consist of ashy hyperpigmented patches on the temple, around the mouth, and on the abdomen, hands, and feet in light skin-persons; hence, the name kala-azar (in Hindi, black sickness). Other findings include hair and skin depigmentation (in Kenyan patients),40 cutaneous nodules and mucosal ulcers (in Sudanese patients),40 trichomegaly (Pitalugo’s sign), petechiae, and jaundice.40

Without treatment, the fatality rate in developing countries approaches 100% in 2 years with the major complications being cachexia, secondary infections, enteritis, and pneumonia. Hemolytic anemia, acute renal damage, and severe mucosal hemorrhage are less common.

Most coinfection cases have intravenous (IV) drug use as a common denominator86 and represent diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, since VL precipitates the onset of AIDS and HIV increases the risk of VL. The problem is mostly described in Spain, Italy, France, and Portugal.82,86–89 L. infantum is the major causative agent; however, other Leishmania species that do not normally visceralize have been isolated.80,81,90 MCL-, PKDL-, and DCL-like pictures may result91 and cutaneous lesions are highly variable.71 Multiple dermatofibroma- and Kaposi’s sarcoma-like papulonodular lesions may occur,86 and should be differentiated from parasitic colonization of Kaposi’s sarcoma.92 The presence of amastigotes in atypical locations tend to correlate with the degree of immunosuppression.93 People with both conditions have worse prognosis, shortened survival time, higher relapse rate and inferior response to treatment compared with HIV-negative patients. VL is now being proposed to be integrated in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical category C as an AIDS-defining illness.3

PKDL is extremely rare in the NW and is mostly seen, in two major forms, in Sudan and India (eTable 206-2.1). As the name implies, it is a cutaneous manifestation of VL that usually develops months to years after resolution of VL, and rarely during its treatment.96,98 In India, PKDL is the most common skin manifestation of leishmaniasis (eFigs. 206-10.1 and eFigs. 206-10.2). Affected patients are the major reservoirs of the infection.98 High blood concentration of the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin-10 in VL patients is predictive of PKDL development. The parasite count is low and detection of organisms is not always possible. With polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, however, Leishmania parasites are recovered in skin lesions in up to 83% and 94% of Sudanese and Indian PKDL, respectively. The development of skin lesions in PKDL is closely linked to Leishmania-specific lymphocyte reactivity, or in HIV patients, to immune reconstitution during HAART treatment. The reason behind the two major clinical forms of PKDL remains essentially unclear.94

Sudan | India | |

|---|---|---|

Interval between VL and PKDL | 0–6 months | 2–3 years |

Incidence | 50% | 5%–10% |

Organism | Leishmania donovani | Leishmania donovani |

Presentation | Punctuate measle-like papular eruption first over the face, forearms, and legs. | Hypopigmented (Fig. 206-10.1)/erythematous patches and/or butterfly erythema, photosensitivity. Later on, lesions disseminate, become papulonodular, and coalesce mainly over the face leading to leonine facies (Fig. 206-10.2) |

Mucosal involvement | Rare ocular involvement: conjunctivitis, blepharitis and anterior uveitis.95 | Possible (mostly of mouth and larynx) and caries a worse prognosis. Possible ocular involvement ranging from keratitis/blepharoconjunctivitis to blindness.96,97 Sexual transmission possible with genital involvement. |

Course/management | Self limited within months.40 Systemic treatment recommended for long-standing lesions (>1 year), mucosal involvement, and/or uveitis94 | Systemic therapy recommended.96 |

Caused by L. tropica, this variant has been described among American veterans of Operation Desert Storm. Visceral infection manifests as fever, malaise, and variable hematologic and hepato-gastrointestinal findings. Classic signs of VL are absent and the skin is usually not involved; however, a recent report in a young Afghani refugee living in the United States demonstrated cutaneous lesions.99 Positive culture from bone-marrow aspirates and good response to antimonials are typical.

This term refers to an id reaction consisting of a diffuse, asymptomatic, and symmetric papular eruption in the setting of acute LCL or LR.100 It typically resolves within 8 weeks of its appearance. Leishmanid may develop during treatment and is not an indication to withhold therapy.47

Given the potential treatment toxicity, confirmation of the diagnosis is always mandatory. Even when smear, histology, and culture results are combined, the parasite may not be detected in 10%–20% of cases.40,54 The diagnostic challenge is often greater in NW disease and in chronic lesions.63,103 The sensitivity of both tissue smear and culture approaches 90% when specimens are taken during the first weeks of infection.3 The best approach is to use several diagnostic methods.

Taken from the infiltrated margin, a skin biopsy may be divided into three parts: one for an impression smear, one for histological examination, and another one for culture.

Several smear techniques may be used with a success rate ranging between 50% and 80%.40 They are obtainable from fine needle aspirates or tissue scrapings, air-dried, fixed with methyl alcohol, stained with Giemsa stain, and viewed under oil-immersion microscopy. Impression smears, made by gently pressing the skin biopsy against a glass slide 2–5 times, provide better sensitivity than H&E examination.104

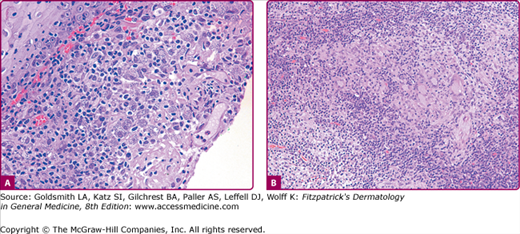

The histopathologic examination of early lesions of LCL reveals a dense and diffuse mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate composed predominantly of histiocytes, and scattered multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells105 (sometimes with intracytoplasmic homogenous eosinophilic immunoglobulin material called Russell bodies). The hallmark of the disease (in around 70% of the cases) is the presence of numerous extracellular and intracellular (within histiocytes) amastigotes (also known as Leishman–Donovan bodies) (Fig. 206-11A).40 Giemsa stain stains the parasite nonmetachromatically and the kinetoplast bright red. The organisms may also be highlighted by the Wright and Feulgen stains. Monoclonal antibodies such as G2D10 can identify amastigotes and promastigotes in smear, biopsy or culture specimens, constituting a rapid screening test for leishmaniasis.106 The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases characterized by parasitized macrophages. The presence of halo surrounding the yeasts in Histoplasmosis, safety pin-like encapsulated Donavan bodies in Granuloma inguinale, and Mikulicz cells in Rhinoscleroma distinguishes these conditions from Leishmaniasis. Other considerations are blastomycosis, paracoccidiomycosis, toxoplasmosis, and trypanosomiasis. As the lesion evolves, the number of amastigotes per section decreases and the histology approaches that of chronic LCL where the predominant histologic pattern is nodular/diffuse noncaseating tuberculoid granulomatous dermatitis (Fig. 206-11B). Epidermal hyperplasia and ulceration are variable. Scarring with marked loss of elastic fibers may be seen.

Figure 206-11

Histologic examination (hematoxylin and eosin). A. Acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. Moderately dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with numerous parasitized macrophages containing amastigotes (Leishman bodies). B. Chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Tuberculoid granulomatous dermatitis. Note the presence of multinucleated giant cells, the surrounding lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and the absence of parasites.

In DCL, a diffuse infiltrate composed of vacuolated macrophages with numerous intra- and extracellular amastigotes is characteristic. The major differential diagnosis is lepromatous leprosy. In MCL, the histopathologic findings are similar to those of LCL but organisms are usually sparse. In PKDL, Pautrier-like epidermal microabscesses and a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with papillary dermal edema (in early lesions) are characteristic.47

Culture (at room temperature), by means of a biphasic medium such as Novy-Mac-Neal-Nicolle (NNN) or chick embryo medium, is the gold standard of diagnosis, but with a sensitivity of only 50%.40 It can be performed using aspirates, scrapings or fresh skin biopsies.69 Promastigotes often appear after several days but occasionally may take few weeks. Species identification is not possible based on their morphology.

Molecular techniques using species-specific oligonucleotide probes for kinetoplast DNA may be used on all specimens. PCR methods are particularly useful and offer superior specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis, MCL, and VL, especially in cases where organisms are scarce.107–111 Their widespread use, however, is hindered by cost as well as by the technical expertise they require. False-positive reactions and species identification in NW-CL may be at times problematic.11

Isoenzyme analysis is currently considered to be the gold standard for Leishmania speciation. It consists of enzyme electrophoresis of cultured promastigotes and is based on the fact that morphologically similar promastigotes of different species have different enzyme profiles; however, it is lengthy and costly.

Serology in cutaneous leishmaniasis is not useful due to its low sensitivity (antibodies present in low titre112) and specificity (due to cross-reaction with leprosy, malaria, and other trypanosomal infections).

The Montenegro skin test (Leishmanin) is analogous to the tuberculin test and consists of phenol-killed promastigotes injected in the dermis.3 This allows the detection of exposure to Leishmania without distinguishing between past and active infection.113 Up to 50% of people living in endemic areas may test positive without a history of previous or active disease. The test is positive once crusting has developed, and negative in anergic states such as DCL and PKDL or often in lesions (less than 3-months-old).

Laboratory animal inoculation (xenodiagnosis) is useful when the parasite load is low.40 Electron microscopy offers no advantage over light microscopy and its use is limited.40

In VL, microscopic detection and/or culture of parasites in tissue aspirates from spleen (sensitivity >97%), lymph nodes (sensitivity 60%), or bone marrow (sensitivity 55%–97%) is diagnostic. However, as these techniques are invasive, several serologic and molecular methods have been developed. Anti-K39 antibody based on a recombinant antigen from L. chagasi has high sensitivity and specificity. It is an immunochromatographic strip test using finger prick blood and is helpful in resource-poor regions. As a last resort, PCR of peripheral blood or tissue aspirate can be done and is extremely sensitive.114

|

The clinical course is disease dependent. In general, lifelong species-specific immunity follows drug-induced cure or natural resolution.115 Cross-species immunity may also develop.116 Sterile immunity does not occur and persistent tissue infection seems to be the rule even following adequate therapy.39,117–119

Given the clinical diversity of leishmaniasis and the lack of adequately controlled therapeutic trials, each case needs to be individualized based on the parasite species (Table 206-3), extent of the disease, host immune and nutritional status, presence of intercurrent diseases, geographic region, and cost, availability and toxicity of the various therapeutic options. In general, NW-CL tends to be more severe and progressive than OW-CL. In addition, NW-CL caused by L. braziliensis may eventuate into “espundia,” thus necessitating systemic therapy. As a rule, patients should be monitored until the lesions have completely healed. Follow up at 6 months is appropriate.

OW-CL | Leishmania major | Expectant observation Local therapy |

Multiple, progressive or sporotrichoid | Systemic therapy | |

Leishmania tropica Leishmania aethiopica Leishmania infantum | Systemic therapy | |

NW-CL | Leishmania mexicana complex | Expectant observation Systemic therapy |

NW-MCL | Leishmania braziliensis Complex | Systemic therapy |

Since most lesions caused by L. major and L. mexicana heal spontaneously within 4 months, an expectant approach is favored as it may confer protective immunity. Multiple, persistent, progressive, deep, sporotrichoid, and secondarily infected lesions should, however, be treated as well as lesions on cosmetically or functionally important sites such as joints.

Local therapy (Box 206-3) is appropriate for small, noninflamed and localized lesions that are not at risk to progress to MCL. Topical imiquimod alone is ineffective.141 Systemic therapy is reserved for complicated CL such as DCL and CCL, MCL, VL, relapsing disease, or disease complicated by HIV coinfection. In general, OW-CL requires shorter courses compared to NW-CL. Systemic therapies used for leishmaniasis are summarized in Table 206-4. Sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate are pentavalent antimony derivatives with slightly differing antimony concentrations and comparable efficacy and safety profiles. They are the mainstay of systemic treatment.178 Indian VL is treated with 20 mg/kg/day intramuscularly or IV once daily for 40 days versus 28 days if the disease is contracted elsewhere. Antimony resistance is a serious issue in India and in Iran.179–182 Resistant cases may benefit from combining antimonials with pentoxifylline,156 allopurinol,183–186 paromomycin,187,188 azithromycin,189–191 IFN-γ,192–194 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor,195 and topical imiquimod.196,197

|

Systemic Treatment/Dose | Mechanism of Action | Indications | Effectiveness | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pentavalent antimonials: sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) IV and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) IM/IV 20 mg/kg/day for 20–30 days | Inhibition of glycolysis and oxidation of fatty acids of the parasite |