Latissimus Dorsi Flap Breast Reconstruction

Dennis C. Hammond

Michael A. Loffredo

Reconstruction with autologous tissue provides the patient with a reconstructed breast created with her own tissues, obviating the potential complications associated with a prosthesis. The disadvantage with this strategy is related to the creation of an additional donor site with scarring and potential morbidity. Although reconstruction with tissue expanders and implants eliminates the need for the additional donor site, the potential complications associated with these devices are a concern. The latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap (LDF) seems to offer no advantage as, most commonly, tissue expanders and implants are still required, and the additional donor site is created on the back. For this reason, the LDF remains a distant third option for many reconstructive breast surgeons. With the development of newer and more effective tissue expanders and implants, however, the advantages of combining these devices with the well-vascularized LDF have generated a resurgence of interest in the technique. This chapter focuses on the technical strategies for optimizing the use of the LDF with tissue expanders and implants.

OPERATIVE STRATEGY

The LDF was originally described in 1906 by Iginio Tansini in Italy.1 It was used to reconstruct mastectomy wounds at the time, but soon fell from favor, to be rediscovered in the late 1970s.2,3 Since its rediscovery, the flap has been used to reconstruct nearly every part of the body, as both a pedicled and a free flap. The LDF is a reliable and richly vascularized flap, and the proximity of the flap to the anterior chest wall makes it an ideal choice for providing the muscle, fat, and skin for use in reconstructing the breast after mastectomy. Sacrifice of the muscle creates a negligible functional deficit except in extremely athletic women.4,5,6 Transposition of the flap from the back to the anterior chest wall provides a healthy layer of soft tissue that can line the mastectomy defect, effectively softening the edges of the wound and thus recreating the gentle curves of the normal female breast. By adding any one of the numerous different styles of expanders and implants under the flap, the volume that is inherently lacking in the flap can be provided to restore the breast to its natural size and contour.7,8,9,10 Using this as a basic strategy, there are several variables both in flap design and elevation, as well as in expander and implant choice, which can be manipulated to maximize the aesthetic quality of the result, while minimizing the donorsite morbidity and potential complications.

Flap Elevation

Historically, use of the LDF has involved transposing only the muscle to the mastectomy defect with an isolated island of skin and fat of varying size positioned on top of the muscle. Although this can effectively provide cutaneous cover for the breast, a more effective technique for providing volume is to harvest the deep layer of subcutaneous fat with the muscle beyond the skin island. The deep thoracic fascia provides a readily recognizable anatomic landmark that guides dissection and even allows the deep fatty layer below the fascia to be harvested beyond the borders of the muscle. By increasing the overall volume of the flap and creating a volume-added latissimus flap, the ability to fill in and soften the margins of the mastectomy defect is enhanced.

Expander/Implant Choice

Recent developments in expander and implant design have resulted in a wide array of devices available for use in reconstruction. Choosing between round and anatomically shaped devices that are either textured or smooth and filled with either saline or silicone provides a variety of choices, which can be strategically exploited to solve individual reconstructive problems. For instance, a thin patient with stark breast contours may be served best by an anatomically shaped silicone gel textured implant. By combining the volume-added latissimus flap with an appropriately chosen expander or implant, excellent results are possible.

MARKING

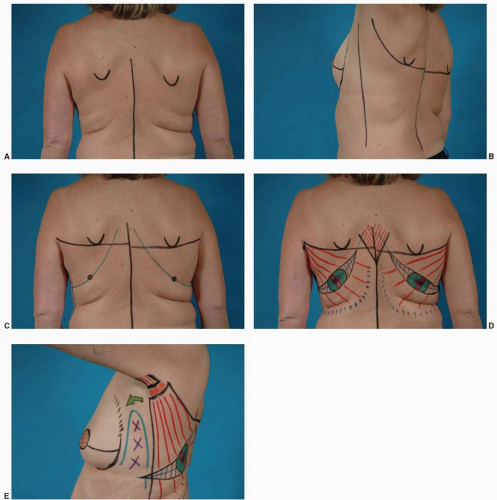

With the patient in the standing position, the borders of the latissimus dorsi muscle are delineated. The midline of the back is identified and the tip of the scapula is marked (Figure 60.1A). With the arm elevated, the anterior border of the muscle is drawn as it extends from the posterior border of the axilla downward toward the iliac crest. The upper border of the muscle is drawn as it extends from the axilla over the tip of the scapula to the midline of the back (Figure 60.1B). The origin of the muscle is marked inferiorly as it curves from the lower midline of the back to the anterior border of the muscle. The inferior segment of the trapezius is drawn as it overlaps the upper medial border of the latissimus as a reminder of this important anatomic relationship.

Once the limits of the muscle have been identified, the location and orientation of the skin island is identified. The skin island is positioned in the center of the muscle to ensure equal soft-tissue coverage of the expander or implant in all directions once the skin island is inset. When a small, circular skin island is required, as is commonly the case when a skin-sparing mastectomy strategy is used, the skin island is positioned directly in the center of the flap. The relaxed skin tension line is identified as it passes through the center of the skin island, and this line guides the drawing of a gentle ellipse around the skin island (Figure 60.1C). By tapering off around the skin island medially and laterally, adequate exposure for flap dissection is provided, while allowing for direct closure of the skin defect without dog-ear formation at the medial or lateral ends of the incision. In this patient, the skin island also includes the addition of an immediate nipple-areola reconstruction using a skate flap purse-string technique (Figure 60.1D).11 Alternatively, the skin island can be left intact to reconstruct the nipple-areola at the second stage.

When a larger skin island is required, as in cases of delayed breast reconstruction, the same strategy is employed, attempting to place the elliptical skin island more or less in the center of the flap and orienting the long axis of the ellipse along the same relaxed skin tension line. The advantage of orienting the long axis of the skin paddle in this fashion is that, despite the scar sweeping up to the upper back, it heals in an acceptable fashion. This is in contradistinction to other scar orientations, which can be quite

unsightly as the orientation of the skin island crosses the relaxed skin tension lines of the back, resulting in widened or hypertrophic scars.

unsightly as the orientation of the skin island crosses the relaxed skin tension lines of the back, resulting in widened or hypertrophic scars.

FIGURE 60.1. Preoperative markings. A. The midline of the back is marked along with the tip of the scapula. B. With the arm raised, the sweep of the superior border of the latissimus muscle can be drawn in as it courses over the tip of the scapula to the midline of the back. The anterior border of the muscle is identified and marked as it runs inferiorly from the posterior border of the axilla to the iliac crest. C. The center of the muscle is identified and the relaxed skin tension line, which passes through this point, is drawn. This line generally sweeps from superomedial and curves anteriorly across the back toward the abdomen. Placing the incision for the skin island in this line results in the least visible postoperative scar. D. A gentle ellipse is drawn around the circular skin island, tapering off medially and laterally so as to provide a smooth postoperative scar. E. On the lateral view, the zone of adherence marked by the X’s should be respected and these tissues should not be elevated during flap transfer. Instead, the flap is optimally passed through a tunnel created high in the axilla and dropped into the mastectomy defect. This preserves the lateral breast contour, which is a landmark that can be difficult to create with internal sutures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|