15 Latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction

Synopsis

The latissimus flap includes a large well-vascularized flat muscle that is well suited for dealing with poorly-vascularized or radiated defects, contour deformities following breast conservation therapy, or for covering an implant.

The latissimus flap includes a large well-vascularized flat muscle that is well suited for dealing with poorly-vascularized or radiated defects, contour deformities following breast conservation therapy, or for covering an implant.

Placement of a tissue expander under the latissimus muscle allows postoperative adjustment of breast volume and ultimately better symmetry with the opposite breast.

Placement of a tissue expander under the latissimus muscle allows postoperative adjustment of breast volume and ultimately better symmetry with the opposite breast.

Complete mobilization to reach medial breast defects may require the partial release (90%) of the latissimus dorsi insertion. This helps avoid the displeasing bulge in the low axilla, however care must be taken to protect the thoracodorsal vessels.

Complete mobilization to reach medial breast defects may require the partial release (90%) of the latissimus dorsi insertion. This helps avoid the displeasing bulge in the low axilla, however care must be taken to protect the thoracodorsal vessels.

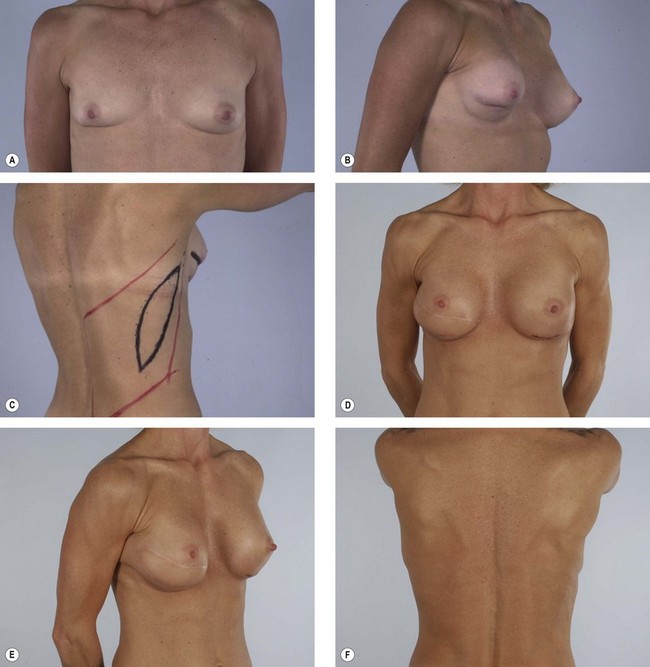

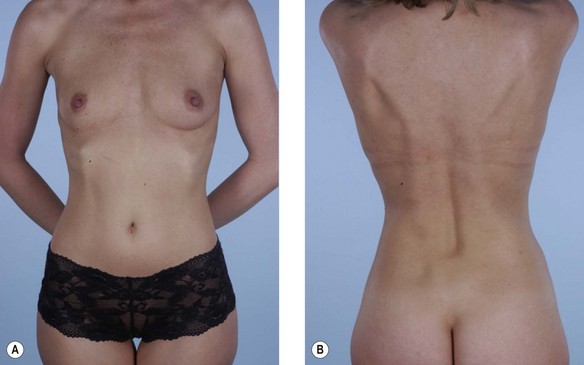

The extended latissimus dorsi flap is a reliable method for totally autologous breast reconstruction and can be considered a primary choice for breast reconstruction, particularly in women who otherwise are at high risk for a TRAM flap or an implant procedure.

The extended latissimus dorsi flap is a reliable method for totally autologous breast reconstruction and can be considered a primary choice for breast reconstruction, particularly in women who otherwise are at high risk for a TRAM flap or an implant procedure.

Introduction

In 2009, the National Cancer Institute reported nearly 200 000 new diagnoses of invasive breast cancer among women, as well as an additional 60 000 cases of in situ breast cancer.1 Progressively more of these women are receiving adjunctive radiation and may not be candidates for implant alone reconstructions. The main workhorses of autologous reconstructions are abdominal based flaps, however the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is an essential reconstructive option. A renewed interest has developed in the latissimus dorsi flap for breast reconstruction due to its reliability, ease of dissection, versatility, and minimal donor site morbidity.

History

The latissimus dorsi muscle flap was originally described by Iginio Tansini (1855–1943) in 1906 for use as an axial musculocutaneous flap to cover mastectomy defects.2,3 This novel technique for post-mastectomy skin closure was in opposition to the teachings of his contemporary, William Hasted. Halsted believed that achieving a definitive cure for breast cancer required removal of all mammary glands, the muscles, the lymph nodes, and wide excision of the overlying skin. The resultant defect was skin grafted or left to heal secondarily. Tansini argued tissue from a distant source could achieve closure without increasing cancer recurrence, what he referred to as an “autoplastic flap of the back”.4 Tansini noted that the flap, if taken as a random skin pattern, usually experienced significant distal tip necrosis, however elevation of the underlying latissimus dorsi with flap harvest resulted in a more reliable flap, from what he mistakenly attributed to as blood supply from the scapular circumflex artery. This technique was popular in Europe through the 1910s and 1920s, however Halsted’s procedure would become the “gold standard” ultimately discounting the latissimus dorsi flap for half a century. Halsted, perhaps in response to Tansini, is notably quoted, “I should not care to say ‘Beware of the man with the plastic operation’ … But to attempt to close the breast wound more less regularly by any plastic method is hazardous, and in my opinion to be vigorously discountenanced”.5 Unfortunately, weary surgeons did not return to Tansini’s progressive techniques until the 1970s.

In 1977, Schneider and colleagues6 described the anatomy of the latissimus dorsi flap and outlined its use for reconstruction of the breast. The technique of the skin island over the muscle was popularized by Bostwick e al.7 in 1978. This allowed for the possible replacement of skin deficiencies and reconstruction of radical mastectomy defects. McCraw et al.8 defined the vascular territory of the latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap, and Maxwell and co-workers9 concluded that the flap could be raised successfully even when the thoracodorsal arterial trunk is ligated, to be sustained presumptively by secondary perfusion.10 This secondary source of circulation to the flap was later shown to be the serratus collateral branch.11 The description of the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap by Hartrampf and colleagues12 in 1979 and the ability to reconstruct the breast completely with autogenous tissue, resulted in the decline of the use of the latissimus dorsi muscle flap. Today, with the advancements in techniques and the tremendous improvements in the aesthetic results of breast reconstruction, the latissimus dorsi muscle flap with its versatility is undergoing resurgence in popularity, as different applications are being developed. It is commonly used in immediate and delayed breast reconstruction to replace skin, to add tissue to reduce the size of the breast implant needed, and to provide more cushion and cover to establish a more natural breast contour. New approaches now allow additional fat and subcutaneous tissue to be harvested over the latissimus dorsi muscle, making purely autologous latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction possible for certain candidates. Partial breast reconstruction is also possible after quadrantectomy or lumpectomy by use of this flap with specific designs. Thus, the latissimus dorsi flap is now frequently used as a primary method of immediate and delayed reconstruction, as well as a supplement to other techniques.

Anatomy

The pattern of circulation of the latissimus dorsi muscle is type V according to the Mathes and Nahai classification.13,14 The dominant pedicle is composed of the thoracodorsal artery, two veins, and the thoracodorsal nerve. The length of the thoracodorsal artery is 8 cm with a diameter of 2.5 mm. This vessel’s relatively large diameter, predictability, and minimal anatomic variation along with the large musculocutaneous unit it supplies make the latissimus dorsi flap a highly reliable donor site as a transposition or free flap for breast reconstruction.

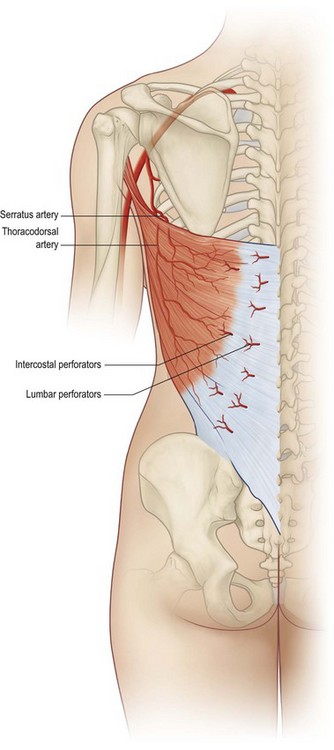

The thoracodorsal artery, along with the circumflex scapular artery, is a branch of the subscapular artery arising from the axillary artery. The thoracodorsal artery gives off a branch to the serratus muscle shortly after entering the underside of the latissimus muscle in the posterior axilla 10 cm inferior to the muscle insertion into the humerus (Fig. 15.1). Understanding of the anatomy in this area is important. In patients with previous axillary dissection, when the thoracodorsal pedicle has been divided, a reversal of flow through the serratus branch can provide adequate blood flow to the flap, allowing the use of the latissimus dorsi muscle as a transposition flap based on its dominant vascular pedicle.11 Once it is in the muscle, the vascular pedicle bifurcates into a large lateral descending branch and a smaller transverse branch. These branches arborize within the muscle to produce extensive intramuscular collateralization.15–17 A precise knowledge of the internal vascular anatomy of the muscle makes it possible to split it for use as a double flap or to preserve half of the muscle to maintain function.

Secondary segmental pedicles enter the underside of the muscle through the lateral perforators row off the posterior intercostal arteries 5 cm from the posterior midline and through the medial perforators row off the lumbar artery adjacent to the site of muscle origin. These perforators allow the use of the latissimus dorsi as a foldover flap to cover midback defects.18,19

Numerous musculocutaneous perforators extend from this rich intramuscular vascular network into the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue, allowing skin islands to be safely designed anywhere within the margin of the muscle. The largest perforators branch from the lateral branch of the thoracodorsal artery, making safest the skin island located in a lateral vertical orientation.15–17

The latissimus dorsi muscle adducts, extends, and rotates the humerus medially. It also assists in securing the tip of the scapula against the posterior chest wall. It is an expendable muscle because function is preserved by the remaining synergistic shoulder girdle muscles. Transposition of this muscle anteriorly has been shown to be well tolerated by patients and results in only a minimal functional deficit,20,21 although dynamic weakness in shoulder extension and adduction may occur.22

Patient selection/indications

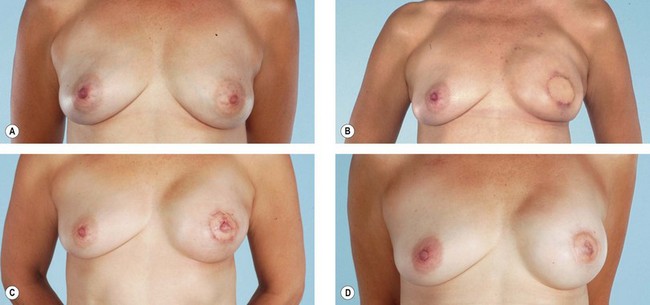

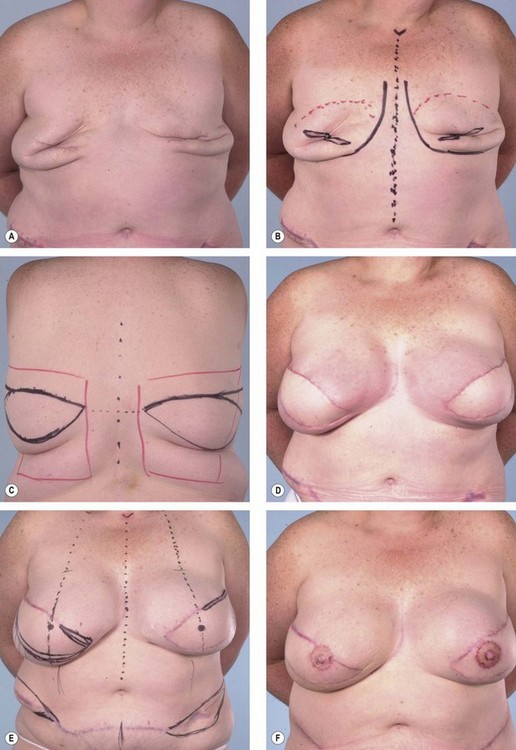

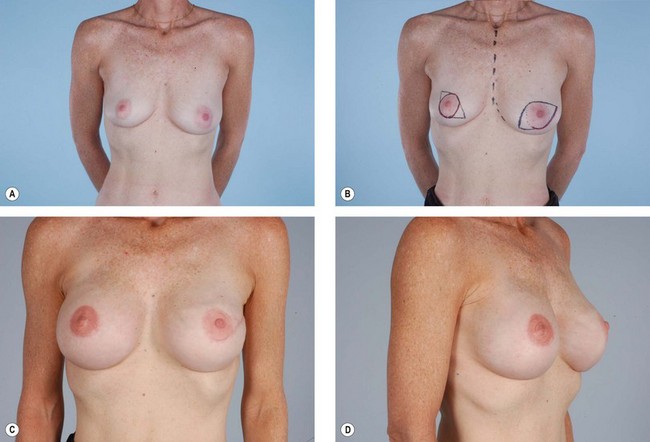

The latissimus dorsi is helpful for breast reconstruction after a skin-sparing mastectomy when a breast prosthesis is part of the plan. The latissimus dorsi skin can be used to replace the missing skin at the site of the nipple-areola, and the muscle can be used to provide improved soft tissue coverage of the breast implant or expander (Fig. 15.2). Placement of a tissue expander under the latissimus muscle allows postoperative adjustment of breast volume and ultimately better symmetry with the opposite breast (Fig. 15.3). Use of the autogenous latissimus dorsi alone without a prosthesis does not allow as much range in the size of the reconstructed breast. In either instance, it is difficult to assess the final volume of the reconstructed breast at the initial setting because of swelling and settling of the breast in the postoperative course.

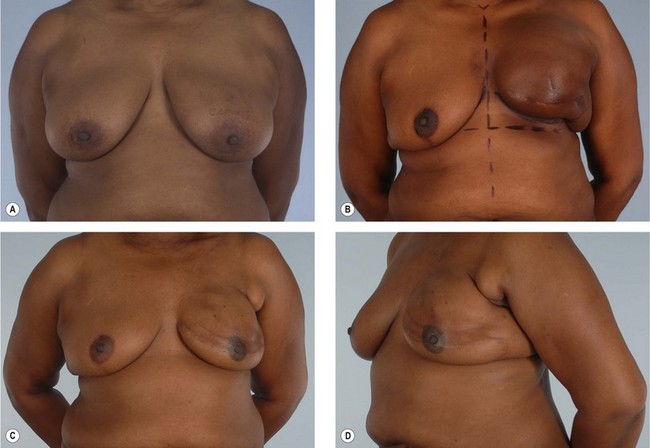

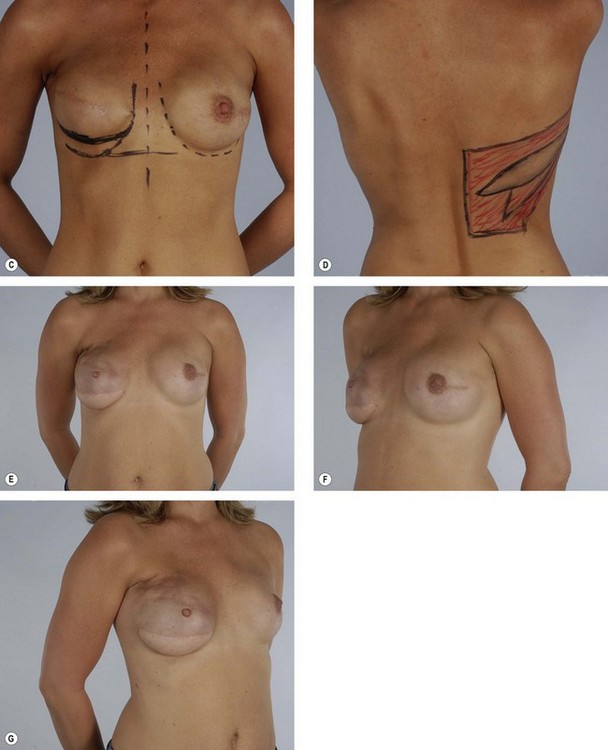

Primary reconstruction can still be accomplished without an implant, especially for women with a small to medium-sized breast.23 An extended latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap without an implant could even be used for a larger breast, especially in patients with at least 2 cm of pinch thickness of back fat.24–28 The texture of the breast and the absence of an implant are major advantages of the purely autogenous breast reconstruction.29 Finally, the latissimus dorsi flap is particularly useful for reconstruction of partial mastectomy or lumpectomy deformities (Fig. 15.4). In such patients, in whom irradiation is certain to aggravate the lumpectomy deformity, the latissimus flap can replace some or all of the missing tissue and thus mitigate the eventual damage.

Specific indications

Patients who are not candidates for a TRAM flap

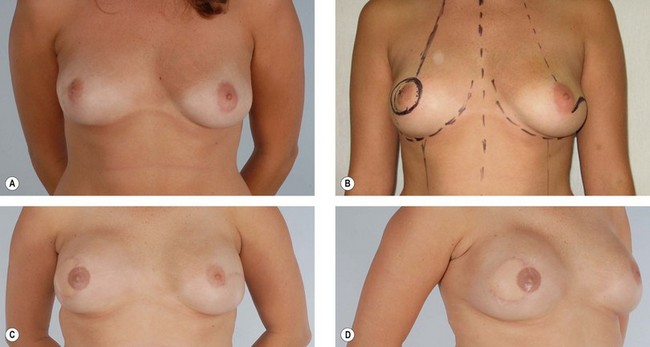

Some women who need supplementary autologous tissue for a satisfactory breast reconstruction or who wish to have purely autogenous breast reconstruction may not be candidates for the TRAM flap.30 This includes women who have had a previous abdominoplasty or TRAM flap, and it may also include women with insufficient abdominal skin or fat (Fig. 15.5). Women who smoke, have diabetes, or are obese may be considered to be too high risk to undergo a TRAM flap. Some women may choose not to undergo on operation as extensive and lengthy as a TRAM flap, particularly in light of the time required for recuperation. When a TRAM flap is not available or advisable, the latissimus flap becomes an obvious option. Aside from being an alternative when a TRAM flap is not the right choice, the latissimus flap has certain attributes and advantages that may make it a better choice. The latissimus flap includes a large well-vascularized flat muscle that may be better suited for dealing with poorly vascularized defects or for covering an implant. In patients with small defects, particularly laterally, the latissimus may be the best choice.

Previous irradiation during breast conservative therapy

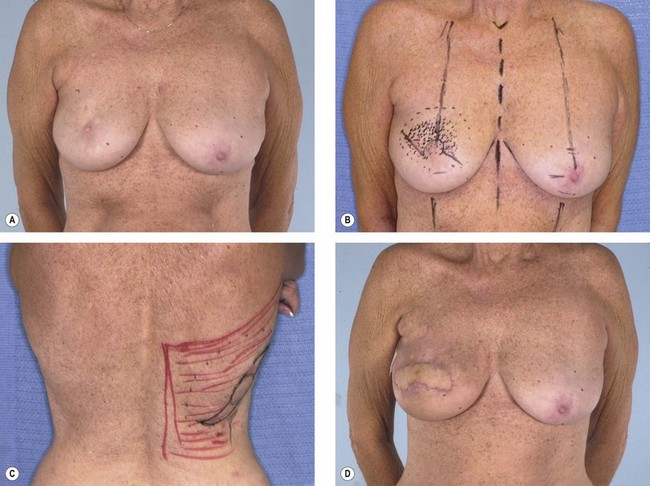

Several papers have discussed the detrimental effects radiation has on tissues and breast reconstruction. Contracture, wound healing problems, implant exposure, infection, skin necrosis and pigmentary changes are all commonly associated with radiation therapy (Figs 15.6, 15.7). If the consultation takes place after radiation therapy, it is important to determine the indications for the radiation, the dose and site of the radiation, and most important, the quality of the remaining tissues. The presence of radiation damage is significant because reconstructions in irradiated tissues, regardless of the method, always lead to a diminished result and a higher rate of complications. Large doses of radiation, as high as 10 000 cGy, typically leave the tissues feeling inelastic, tight, and thickened.31 This is especially troublesome when the radiation is given during the reconstruction when a tissue expander is already in place. In any case, reconstruction with an implant alone may not be possible and may result in significant complications or, at the very least, a disappointing result. Reconstruction with the help of autologous tissue may be critical because it brings well-vascularized tissue to the ischemic chest wall. The pedicled latissimus flap provides a moderately sized skin island as well as a large amount of well-vascularized muscle. It is a hardy flap that can be used despite irradiation to the axilla.

The skin flaps of a previously irradiated breast are unreliable from a circulatory point of view and inelastic from a tissue expansion perspective. If no radiation therapy is anticipated, the addition of a latissimus musculocutaneous flap at the time of an immediate postmastectomy reconstruction makes the operation safer and improves the odds that the ultimate result will be satisfactory.32 Adding a latissimus flap to the inferior pole of the breast (as opposed to opening the mastectomy scar and placing the skin paddle mid-breast) has helped in creating a favorable contour for the breast when combined with an implant. Critical to this concept is that the latissimus flap be added only after radiation therapy has occurred. Adding the latissimus skin paddle to the inferior pole is critical in releasing the non-compliant radiated skin and soft tissue that prevents the implant from creating the normal breast contour and ptosis (Fig. 15.8). In a review of consecutive patients over 5 years at our institution, 15% received radiation following immediate reconstruction.31 It was found that for patients with expander based reconstructions, the majority went on to successful two-stage device-only reconstructions (60%). For the remaining 40%, the addition of a latissimus dorsi flap to the lower pole provided adequate release of constricted lower mastectomy flaps with an improved cosmetic appearance.

Partial mastectomy defects

In women in whom a lumpectomy would establish an undesirable defect, the latissimus flap can replace or make up for the missing tissue.33