Kidney Transplantation with Complex Arterial Anatomy

Carlton J. Young

DEFINITION

Live donor or deceased donor renal transplantation can be complicated by complex arterial anatomy. This complex anatomy can be the result of donor factors or procurement errors. Regardless of the cause, the inability to correct complex arterial anatomy will result in the inability to transplant the kidney or loss of the kidney due to arterial vascular thrombosis. Many of the techniques that follow were developed and perfected in the 1980s.1,2,3 The incidence of multiple renal arteries has been estimated to be between 18% and 30%, with the incidence of bilateral multiple renal arteries as high as 15%.4

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Procurement of a renal allograft is covered in another chapter. One way to minimize complex renal arterial anatomy is being cognizant that anatomic variations can occur. For living donor kidneys, preoperative imaging should give the procuring surgeon good insight to the arterial anatomy. Many centers are more willing to accept donors with two or even three renal arteries. The use of automatic vascular staplers yields shorter arteries than those used in the era of open donor nephrectomy.

Deceased donor complex anatomy can be unavoidable when accessory arteries are missed during procurement. This is often the case for lower pole arteries that arise near the aortic bifurcation. In addition, arteries can be damaged by carelessness when dissecting in the hilum.

The one advantage of deceased donor kidneys is that an aortic cuff can be used for the anastomosis.

Prior to implanting the kidney, the surgeon must correlate the recipient arterial anatomy with the donor kidney. Recipient vascular calcifications may limit the landing zone for the renal arterial anastomosis, potentially affecting donor arterial reconstruction.

Try to sew multiple arteries individually into the recipient iliac artery when possible rather than using the complex reconstructions discussed in the following text. However, anastomosing individual arteries is not always possible.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Reconstructing complex anatomy is minimized with careful procurement. Removing kidneys en bloc is safer than removing them individually in situ. Kidneys should then be separated on the back table where the en bloc kidneys can be viewed from all directions. Be cognizant of the possibility of a distal lower pole artery.

Assure the entire kidney is well flushed. If a section has not been adequately flushed, look for a missed artery.

Upper pole arteries can be sacrificed if they are small (i.e., supply less than 10% of the renal parenchyma). Lower pole arteries should not be sacrificed; they may be the sole blood supply to the ureter. Lower pole arteries as small as 1 mm should be salvaged.

One way to determine the extent of supply of an artery is to inject heparinized saline mixed with indigo carmine into the artery.

Once the hilum is cleaned of excess fat and the lymphatics ligated, the full extent of the complex anatomy can be appreciated. The surgeon should then assess the recipient iliac artery. At this time, decisions about reconstruction should be made.

TECHNIQUES

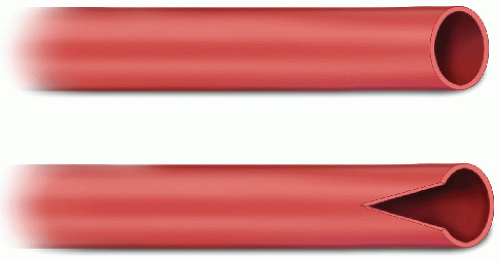

Simple spatulation (FIG 1)—Simple spatulation facilitates enlarging the orifice of a small accessory renal artery (usually from the lower pole). Anastomosis can then proceed after arteriotomy and use of a small (e.g., 2.8 mm) coronary hole punch. A 7-0 or 8-0 Prolene can be used in a running or interrupted fashion. This technique is useful when the arteries are far apart and there is adequate recipient length on the iliac artery to allow two anastomoses. Perform the most proximal anastomosis first. This is usually the larger of the two arteries. There is no need to reperfuse the kidney through the upper pole artery before completing the lower pole anastomosis as long as the anastomoses can be performed expeditiously. If excessive warm time is expected, the upper pole artery and vein can be opened. Importantly, a perfused kidney is larger, diminishing space to perform the lower pole anastomosis.

Two arteries on a common Carrel patch but with a large distance between orifices (FIG 2)—When two arteries share a common cuff but are separated by a large distance, do not create large recipient arteriotomy. Instead, the intervening section of the patch can be removed and the two arteries may be anastomosed separately. Alternatively, the Carrel patch can be reconstituted with a running 6-0 Prolene stitch. This stitch starts

at one end of the cut patch and goes to the opposite end, making sure the knot is on the outside of the patch.1,2

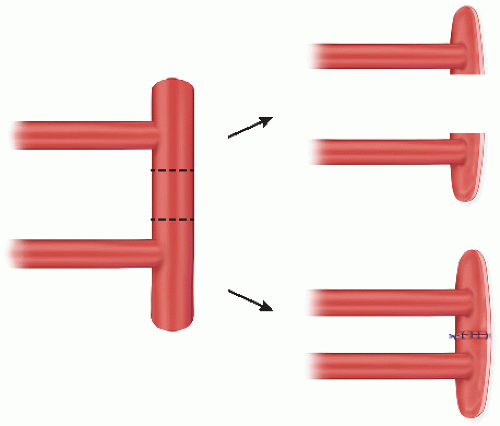

Two arteries with no patch (FIG 3)—Multiple arteries with no patch are common in living donor kidneys and in deceased donor kidneys where an error has occurred. If the recipient arterial anatomy precludes individual anastomoses, then the two arteries can be sewn together. The distance of the spatulation is between 3 and 5 mm. This distance should be enough to allow access to the lumen without excessive manipulation of the intima. Care must be employed to minimize injury to the intima. Excessive handling of the intima will result in a higher rate of thrombosis. Two 7-0 or 8-0 Prolene sutures are placed on either side of the “V.” Once the suture is tied to itself, one side is sewn in a running fashion. Once the apex of the spatulation is reached, the suture is tied to itself again. This process is repeated for the opposite side as well.1,2 Heparinized saline can then be used to test for patency. The most likely location of a leak is at the crotch of the “V.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree