Kawasaki Disease: Introduction

|

Kawasaki disease (KD), the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed nations, is a multisystem inflammatory illness that particularly affects blood vessels, especially the coronary arteries. About 25% of untreated children develop coronary artery abnormalities, including dilatation and aneurysms that can lead to myocardial infarction and sudden death.1,2 The etiology is unknown, but clinical and epidemiologic data support an infectious cause. In KD, an intense inflammatory cell response develops in a wide array of organs and tissues3; in medium-sized arteries such as the coronary arteries, this response can damage collagen and elastin fibers in the vessel walls and lead to loss of their normal structural integrity with resultant ballooning or aneurysm formation. Despite a limited understanding of KD pathogenesis, a very effective therapy exists in the form of IVIG and aspirin; when given in the first 10 days of fever, this therapy reduces the prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities from 25% in untreated patients to 5% in those who receive the therapy.4 Because the etiology is unknown, no diagnostic test exists, and the diagnosis is made clinically. Classic KD is diagnosed in a patient with prolonged fever and four of five other clinical findings (Box 167-1). However, incomplete forms of illness are well-recognized, in which a child manifests prolonged fever with fewer than four other clinical features of the illness and subsequently develops coronary artery abnormalities. The existence of these incomplete forms of illness results in a major diagnostic dilemma for physicians in establishing the diagnosis accurately in children with prolonged fever of uncertain cause.

Fever ≥5 days,a high spiking and intermittent, with at least four of the five clinical featuresb

|

Historical Aspects

KD is named for Dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki, a Japanese pediatrician who first recognized the clinical features of the illness. He described 50 cases of a new illness in 1967 in the Japanese-language literature that he termed mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome.5 It was not until later that some of the children with this newly described illness experienced sudden death; autopsy revealed myocardial infarction from thrombosis of coronary artery aneurysms. Prior to Dr. Kawasaki’s description of the clinical features, KD was recognized only by pathologists at autopsy, who called the disease “infantile periarteritis nodosa.”6 Dr. Kawasaki described the illness in the English-language literature in 1974; this report was closely followed by a description of the same illness, observed independently in the early 1970s in Hawaii by Dr. Marian Melish and colleagues.7,8 Since that time, it has become clear that although the attack rate of KD is highest in Asian, particularly Japanese, Korean, and Chinese children, all racial and ethnic groups around the world are affected by the illness.

Epidemiology

KD is predominantly an illness of young children, with 80% of cases occurring in children ages 6 months to 5 years.9,10 However, infants less than 6 months of age can be affected, often manifest incomplete forms of the illness, and can have particularly severe KD.11,12 Similarly, KD can occur in older children and teenagers, in whom the diagnosis is often delayed, and who may also have more severe KD with a higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities.13–15 Therefore, the diagnosis must be considered in all pediatric age groups.

Boys are more commonly affected than girls at a ratio of 3:2. The incidence of KD is approximately tenfold higher in Japanese than in Caucasian children.9,10 About 1 in 100 Japanese children develop KD by the age of 5 years; the peak age of illness is 9–11 months of age in both Japan and the United States.9,16 The higher attack rate in Japanese children persists in those who adopt a Western diet and lifestyle, and is likely related to a genetic predisposition to KD among Asian children.17 The risk of KD in siblings is tenfold higher than in the general population, and the incidence of KD in children born to parents who had KD is twice as high as in the general population.18,19 Recurrence is rare, occurring in about 3% of cases in Japan.16

Many epidemiologic features of KD suggest an infectious agent is the cause. Among these are the well-described epidemics of illness17,20–22 and the geographic wave-like spread of illness during an epidemic, compatible with spread of an infectious agent.22 Cases in the United States are more common in the winter and spring.9

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of KD remains unknown. The hypothesis that best fits the available clinical, immunologic, and epidemiologic data is that KD results from infection with a ubiquitous etiologic agent that usually results in asymptomatic infection, but causes KD in a small subset of genetically predisposed individuals. Genetic predisposition is a common theme in susceptibility and host response to infectious diseases. It is likely that KD is polygenic. Intensive investigation of genetic factors influencing susceptibility to KD is ongoing by several international collaborative groups. A functional polymorphism in the ITPKC gene, which is a negative regulator of T-cell activation, has been associated with KD susceptibility and risk of developing coronary artery abnormalities23; it is likely that other susceptibility genes will be discovered in the near future.

KD is often referred to as an autoimmune illness, but there is no compelling reason to classify it as such. The spontaneous resolution of the febrile phase of illness, the rarity of recurrent KD, and the fact that the highest incidence occurs in male infants, a group who rarely develop autoimmune diseases, all argue strongly against this possibility. Immune complexes, although detectable in serum in the subacute phase, are not deposited in tissues and do not appear to play a prominent role in pathogenesis. Although inflammation in KD results in tissue damage, the damage is likely to be primarily the result of an immune response targeting antigen(s) of an infectious agent in the tissue.

Many cytokines are upregulated in KD, which has led some investigators to propose a superantigen as the cause of the illness. However, cytokines are upregulated in many infectious diseases, and the cardinal feature of a superantigen-mediated illness, the paralysis of adaptive immunity,24 is not observed in acute KD. Oligoclonal, antigen-driven CD8 T lymphocyte,25 IgA plasma cell,26 and IgM B lymphocyte27 adaptive immune responses are detected in acute KD.

In KD, an intense inflammatory cell infiltrate is observed in many organs and tissues, particularly in the medium-sized arteries.3 These inflammatory cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases and other enzymes that can disrupt collagen and elastin fibers in the coronary arteries, impairing the integrity of the arterial wall and resulting in ballooning or aneurysm formation.28 The initial insult that causes this immune response is unknown, but the nature of the inflammatory cell infiltrate provides clues. Although neutrophils contribute to the very early inflammatory-cell infiltrate in KD tissues, they are quickly replaced by large mononuclear cells and lymphocytes.2 By two weeks after the onset of fever, the inflammatory infiltrate in the arterial walls largely consists of T lymphocytes (predominately CD8 T lymphocytes), macrophages, plasma cells (predominately of the IgA isotype), and eosinophils.29,30 IgA plasma cells are increased in the respiratory tract, particularly in a peribronchial distribution.31 The presence of IgA plasma cells and CD8 T cells as primary components of the inflammatory infiltrate in acute KD suggests an immune response to an intracellular pathogen with a respiratory portal of entry.29 Sequencing of IgA genes in the arterial walls in acute KD shows an oligoclonal, or antigen-driven, response.26 Synthetic versions of these oligoclonal IgA antibodies identify antigen in acute KD tissues.32 Light and electron microscopic studies show that the antigen detected by KD synthetic antibodies resides in cytoplasmic inclusion bodies that are consistent with aggregates of viral protein and RNA.33,34 Identification of the specific proteins and RNA in the inclusion bodies should lead to identification of the etiologic agent of KD. These studies are hampered by the lack of unfixed tissue specimens from fatal cases, and by the likelihood that the etiologic agent is an RNA virus without significant homology to known viruses, thereby making its RNA sequence difficult to identify.34 It is hoped that advances in high throughput sequencing and bioinformatics analysis will yield the solution to the mystery of the etiology of KD in the near future.

Clinical Findings

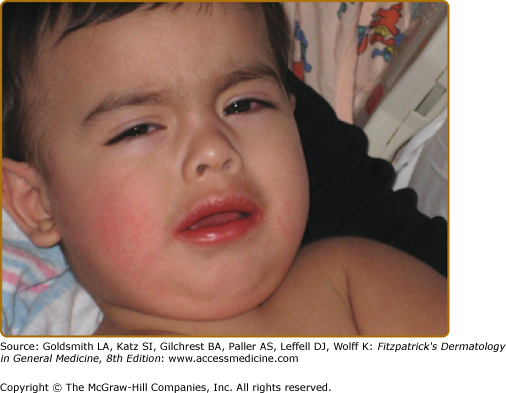

A diagnosis of classic KD is made in the presence of prolonged fever ≥5 days, with four of the following five clinical features in the absence of another explanation for the illness: (1) nonpurulent bulbar conjunctival injection (Fig. 167-1); (2) red, swollen, dry lips, which may crack and bleed (Fig. 167-1); (3) redness and swelling of the hands and feet; (4) rash; and (5) cervical lymphadenopathy, ≥1.5 cm in diameter. Experienced physicians can make a diagnosis of KD before the fifth day of fever in children with classic features. A patient with prolonged fever and fewer than four of the other features of the illness can be diagnosed with KD if coronary artery abnormalities develop. Incomplete (or atypical) KD refers to children with prolonged fever and fewer than four of the other features of illness who have a laboratory profile compatible with KD. Such patients should undergo echocardiography and be considered for treatment with IVIG because KD patients, particularly infants, do not always manifest classic diagnostic criteria during the acute febrile phase of illness, yet can develop coronary artery abnormalities (Box 167-1).

KD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any child with prolonged fever without other explanation. In KD, all clinical features may not be present simultaneously. Therefore, it is important to query parents and physicians who saw the patient during the course of a prolonged febrile illness as to the presence of the other five clinical features of the illness: (1) conjunctival injection, (2) oral mucosal changes, (3) changes of the hands and feet, (4) rash, and (5) cervical adenopathy. Children with KD often have significant enough swelling and discomfort of the hands and feet that they will refuse to pick up objects or to walk. This is not commonly observed in children with most other illnesses in the differential diagnosis of KD and can provide an important clue to the diagnosis. Similarly, extreme irritability is common in KD and not as common in most other illnesses in the differential diagnosis. Without specific therapy, fever in KD is daily, high spiking, intermittent, and lasts for one to two weeks. The illness is often divided into three stages: (1) the acute febrile phase, (2) the subacute phase (that begins when fever resolves and continues until all clinical features have normalized), and (3) the convalescent phase (that follows the subacute phase and continues until the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) normalizes, usually at 6–8 weeks after the onset of fever).

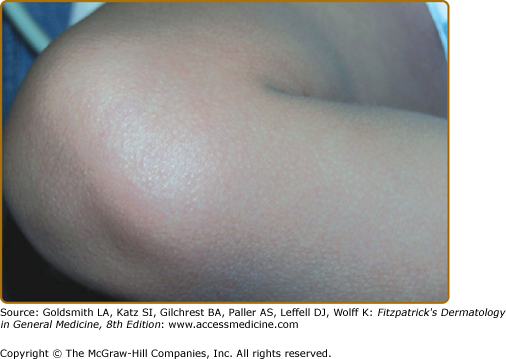

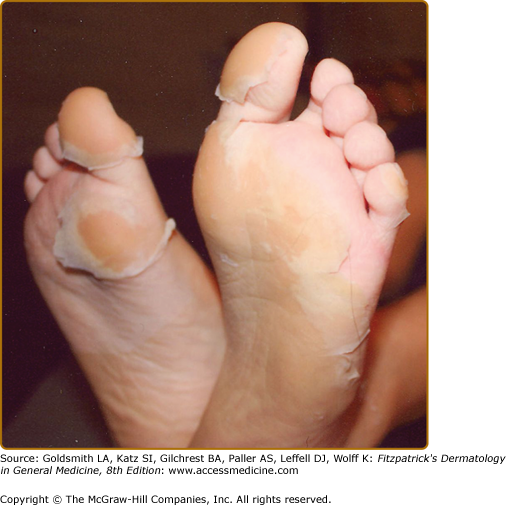

Rash is commonly observed in KD, is most pronounced on the trunk and extremities, and generally takes one of three forms: (1) an erythematous maculopapular exanthema (Fig. 167-2), (2) erythema multiforme with typical target lesions, or (3) a scarlatiniform exanthema. Bullae, vesicles, and ulcerative lesions are not observed, but a fine micropustular rash, especially on the extensor surfaces, occasionally occurs. The rash may be pruritic. In the acute febrile phase of illness, groin erythema and desquamation are commonly observed (Fig. 167-3), and can be mistaken for candidal diaper dermatitis or even a staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. The skin changes in the groin can be seen both in children in diapers and toilet-trained children. Classic periungual desquamation of the fingers and toes does not begin until the second to third week after fever begins, and can progress to involve the entire hand and foot (Fig. 167-4); treatment should be administered well before its appearance. In the third to sixth week after illness, transverse lines across the fingernails (Beau lines) are often apparent. These grow out with the nail.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree