Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Angiosarcoma: Introduction

|

General Considerations

In 1872, the Austro-Hungarian dermatologist Moriz Kaposi described five patients with multicentric cutaneous and extracutaneous neoplasm that primarily affected older individuals.1 This disease, originally described as “idiopathic multiple pigment sarcoma,” was later eponymously designated Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Since then, different variants of this tumor have been described that have distinct epidemiologic features and run distinct clinical courses but show comparable histopathologies.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Several decades of epidemiological data and electron microscopic studies have suggested an infectious agent as an etiologic factor in KS.2,3 This suspicion was substantiated in 1994 when Chang and colleague discovered DNA of an unknown virus in KS lesions.4 This finding led to cloning, isolation, and characterization of a novel human herpesvirus now referred to as KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or alternatively, human herpesvirus (HHV)-8.5,6

HHV-8 is a member of the γ-Herpesviridae subfamily, genus Rhadinovirus.5–9 Its 165-kb DNA genome has been entirely sequenced and shown to contain approximately 90 open reading frames.5,7,8 Many of the HHV-8 regulatory genes are homologous to genes of other Rhadinoviruses, and several are homologous to human genes involved in the regulation of apoptosis, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis.5,9,10 As with other herpesviruses, HHV-8 gene expression is tightly controlled and either associated with viral latency, such as LANA-1, V cyclin, and vFLIP, or lytic viral replication, such as vGPCR, vIL 6, and v-bcl-2.5,10 Several HHV-8 gene products, both of the lytic and the latent viral life cycles, have been shown to transform cells in vitro as well as in animal models in vivo.6,10–13 Therefore, it is generally accepted that this transforming capacity of HHV-8 plays a direct role in the development of KS.

The host range of HHV-8 in vivo and in vitro comprises vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells as well as different types of hemopoietic cells.6 The widely expressed 12-transmembrane light chain of the human cystine/glutamate exchange transporter system xc and the C-type lectin DC-SIGN have recently been proposed as receptors of HHV-8.14,15 The latter is of particular interest since in contrast to the former it is expressed by activated B cells, which are important host cells for HHV-8 in vivo.6,15

The routes of HHV-8 transmission are not yet completely known. The high incidence of KS in homosexual and bisexual patients and the association of tumor development with certain sexual practices originally suggested a role for the sexual transmission of the virus.3 In later epidemiological studies, sexual activities were confirmed as a route for HHV-8 transmission, and it was demonstrated that the transmission risk increases with the number of sexual partners16 and with certain practices such as oral/genital and oral/anal sex.16 By contrast, in areas where the virus is widespread such as in Mediterranean countries and Africa, strong evidence exists that nonsexual transmission among family members16,17 plays a major role. The oropharynx is the site of the most robust viral replication and high HHV-8 copy numbers are present in saliva.18 On the basis of these findings, the nonsexual transmission via saliva is widely assumed to play the most important role in childhood transmission in endemic areas.19 Vertical transmission from mother to child during pregnancy or birth seems not to play an important role for the spread of the virus.16 For the medical profession, it is important to remember that HHV-8 may also be transmitted by blood and blood products as well as from donor organs in the course of transplantations.16,20

HHV-8 is present in all KS-variants,21,22 and the evidence for a causal relationship between HHV-8 infection and KS tumor development is overwhelming. Amongst the most important arguments for the role of HHV-8 in KS pathogenesis are the findings that (1) the HHV-8 viral genome is detectable in KS lesions at all stages regardless of the clinical variant,5,6,21,22 (2) within KS lesions HHV-8 is present in the latent form in virtually all tumor cells,23,24 and (3) KS tumor cells show oligoclonal or monoclonal integration of viral DNA.5,6 Furthermore, the prevalence of HHV-8 is largely congruent with that of KS: in areas of low incidence of KS, such as the United States and Northern Europe, HHV-8 infection is very rare (below 0.1%;16,25 By contrast, in areas where high incidence of KS has been reported such as in southern Italy, HHV-8 prevalence is much higher and approaches 20%.16,26 As expected the highest HHV-8 prevalence has been found in Central Africa in the regions known to be hot spots of African endemic KS. In this region, the seroprevalence in adults ranges from 22% to 71%.16 Similarly, in HIV-1-infected patients in industrialized countries HHV-8 prevalence is highest in homosexual and bisexual men and reflects the incidence of KS in this risk group.16,27

The time span from infection with HHV-8 to development of KS depends on the clinical type. Immunosuppression/dysregulation plays an important aggravating role and leads to disease manifestation in organ-transplant recipients within 1–2 years and in HIV-1-infected patients 5–10 years after infection.16 For classic KS, this time span is far longer and the contributions of either host-related or environmental factors are not yet established.16

In addition to KS, HHV-8 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of pleural effusion lymphoma, a rare B cell neoplasm seen primarily in AIDS patients, and multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD).10,16,28,29 In the former HHV-8 is in variably present and diagnostic, in the latter it is found in the majority (>95%) of HIV-infected patients with MCD but only in about 40% of HIV-negative MCD patients.10 Castleman’s disease has been associated in the past also with classic KS.30

The histogenetic derivation of the KS tumor cells, i.e., the cells lining the irregular vascular-like spaces of early and angiomatous lesions and the cells composing the bundles and interlacing fascicles of solid tumors, has been the subject of intense research interest over the past two decades. The immunophenotype of these cells (i.e., vWF+/−, PAL-E−, CD31+, CD34+, VEGFR3+) characterizes them as part of the lymphatic endothelial differentiation lineage.31,32 The recent demonstration that HHV-8 replicates better in lymphatic than in blood vascular endothelial cells is a further argument for this assumption.33 However, the finding that infection of blood vascular endothelial cells with HHV-8 leads to a phenotypic switch toward lymphatic endothelial cells33,34 leaves the possibility open that an immature angioblast either resident in the skin or circulating and able to differentiate into both endothelial cell lineages is the initial precursor of KS tumor cells.35

Some discussion surrounds the question as to whether KS is a reactive proliferative disorder or a true malignant neoplasm. Analyses of the methylation pattern of the human androgen receptor gene by several investigators have shown that lesions with both clonal and polyclonal proliferations can be identified.36,37 Similarly, studies of HHV-8 terminal repeat sequences have demonstrated both viral mono- and oligoclonality in KS lesions.38,39 Taken together, these findings indicate that KS starts out as a polyclonal disease, i.e., as a reactive process, which with disease progression may develop into monoclonal tumors.

Clinical Manifestations

The typical patient with classic KS is a Caucasian male in his sixties with a Mediterranean or Jewish background. The tumors usually start on the skin as unilateral or bilateral bluish-red (hematoma-like) macules on the distal portions of the lower extremities. These lesions tend to progress only slowly both horizontally and vertically and develop into firm plaques (Fig. 128-1) and, subsequently, into nodules. During tumor progression, the color might change to brownish and the skin overlying the tumor becomes hyperkeratotic and, in particular on the lower extremities, might exulcerate. The tumor surroundings frequently show a pitting edema, which may evolve into fibrosis. Classic KS usually runs a rather prolonged benign course and patients may sometimes live with slowly progressive disease for decades.40,41 After several years, progression (Fig. 128-2) and dissemination to other body sites are frequently seen, and tumors may become manifest in lymph nodes, on mucous membranes and in inner organs, in particular the gastrointestinal tract although it becomes rarely symptomatic.40,41 Since mostly elderly patients are affected by KS, death from other causes may precede its full spread.

The annual incidence rates for classic KS vary greatly in different geographic regions and ranges from 0.14 per million inhabitants (for both women and men) in Great Britain to 10.5 per million in men and 2.7 per million in women in Italy.40 A preponderance of male patients has persisted since the original description with a male:female ratio of about 3:1 noted in large surveys of most regions.40,41 The higher KS incidence in countries surrounding the Mediterranean has led some authors to propose a Mediterranean KS variant as a distinct entity.42 However, since the clinical course is comparable to the one of classical KS, Mediterranean KS will not be treated separately here.

An increased frequency of KS in black Africans in Central Africa was noted several decades before the outbreak of the AIDS pandemic.43,44 In some countries of this region, KS accounts for up to 10% of all malignancies in men.16,43,44 A prevalence of male patients, with ratios ranging from 3:1 in children and up to 18:1 in adults, is seen with endemic African KS.40 The age at onset is lower than that in classical KS—around 35–39 years for males and 25–39 for females.40

According to clinical features, African endemic KS occurs as nodular-, florid-, infiltrative-, and lymphadenopathic-types.45,46 The florid/vegetating and infiltrative variants are characterized by a more aggressive biologic behavior and lesions may extend deeply into the dermis, subcutis, muscle, and bone. Lymphadenopathic African KS predominantly affects children and young adults and may run fulminant courses with rapid progression47; skin and mucosa are affected to a lesser degree. The reasons for the different courses observed in African KS are not clear and potential cofactors have not unequivocally been identified.

During the 1970s, a high incidence of KS was described in organ-transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive therapy with an up to 500-fold increase as compared to the control population.48,49 Transplantation-associated KS is observed predominantly in kidney allograft recipients, while it occurs rarely in recipients of other solid organs and bone marrow allografts.48–50 KS has also been reported in individual patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy for other reasons, most notably the treatment of autoimmune diseases.51–53

The clinical appearance and the course of KS in therapeutically immunosuppressed patients may be slowly progressive as with the classical variant. It can also rapidly disseminate as is the case with AIDS KS. KS can occur as early as 1 month and as late as more than 10 years after transplantation.54 A very important risk factor for developing KS and determining its clinical course is the dose and type of the immunosuppressive drug.40,50 For example, the risk associated with cyclosporine is higher than with other drugs such as glucocorticoids and azathioprine and the disease onset is earlier.49,50 Regression of KS can be achieved by reduction or withdrawal of the immunosuppressive agent (see below). Similarly, rapid tumor progression can occur after increase of the dosage.49,50 In transplantation-associated KS, a preponderance of male patients with a ratio of about 3:1 is observed,50 and in geographic regions with a high incidence of classical KS as well as in ethnic groups with a higher risk of KS development, the risk for transplantation-associated KS is increased.50 Skin involvement is most common in transplantation-associated KS. In a large series, skin involvement was found in more than 85% of the patients with transplantation-associated KS, whereas less than 15% had visceral (gastrointestinal, lungs, lymph nodes) disease without skin involvement.50

A major harbinger of the AIDS pandemic was clusters of young homosexual men suffering from KS identified in large US cities in 1981.55 During the first decade of the AIDS pandemic, KS had been diagnosed as the AIDS defining disease in more than 20% of HIV-1-infected patients in Europe.56 Despite a decline in recent years, KS is still the most frequent AIDS-associated tumor in homosexual patients. Other patient groups at risk for AIDS including intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs, blood-transfusion recipients, and children born to HIV-positive mothers in industrialized countries are far less affected.3,57 The situation is different in Africa where KS is the most frequent tumor arising in HIV-1-infected patients independently of their risk group and includes children suffering from AIDS.58,59

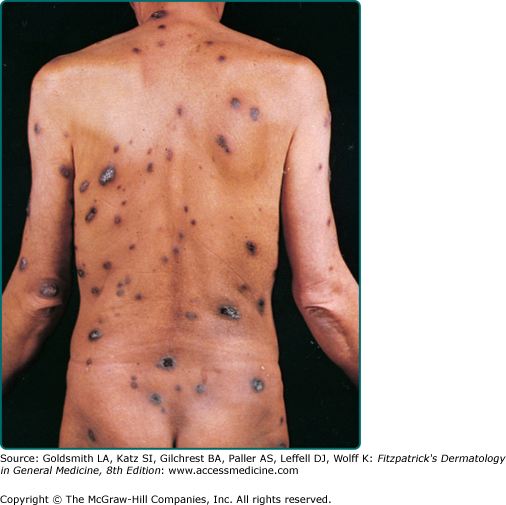

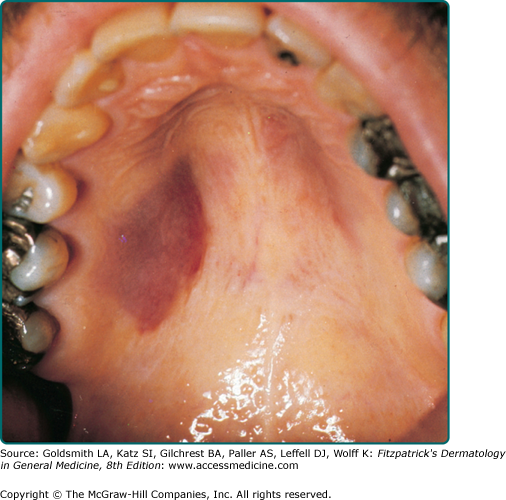

Clinically, AIDS KS differs from classical KS by its more rapid course and its rapid multifocal dissemination: early AIDS-KS lesions that appear as small oval violaceous macules develop rapidly into plaques and small nodules, which frequently are present at multiple locations at disease onset and have a tendency for rapid progression. In contrast to other variants of KS, the initial lesions in AIDS patients frequently develop on the face, especially on the nose, eyelids, ears, and on the trunk, where the lesions follow the relaxed skin tension lines (Fig. 128-3). If untreated, disseminated AIDS-KS lesions may coalesce to form large plaques involving large parts of the face, the trunk, or the extremities leading to functional impairment. The oral mucosa is frequently involved and represents the initial site of a 10%–15% of AIDS KS (Fig. 128-4). Involvement of the pharynx is not uncommon and may result in difficulty in eating, speaking, and breathing.60

The involvement of extracutaneous sites occurs more rapidly and more dramatically in patients with AIDS KS than those with classical KS. Besides the oral mucosa, KS lesions are most frequently found in the lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal tract, and the lungs.61–63 Although gastrointestinal KS is usually found when cutaneous lesions are present, exclusive gastrointestinal involvement is possible as is noted in transplantation-associated KS. KS lesions have a predilection for the stomach and duodenum and can cause bleeding and ileus. Although visible by gastroscopy, such lesions are underdiagnosed histologically because they are located in the submucosa and may escape the biopsy forceps. Pulmonary KS can cause respiratory symptoms such as bronchospasm, coughing, and progressive respiratory insufficiency.62 Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy is most appropriate for the diagnosis of pulmonary KS.

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous KS depends on the clinical stage and hematoma, pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma, melanoma, pyogenic granuloma, spindle cell hemangioendothelioma, arteriovenous malformations (pseudo-KS), severe statis dermatitis (pseudo-KS), bacillary angiomatosis, angiosarcoma, cavernous hemangioma, angiokeratoma, and nodal myofibromatoma. In the oral mucosal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and melanoma have to be considered (Table 128-1).

Most Likely

|

Consider

|

Always Rule Out

|

Histopathology

The histopathology of KS is dependent on the stage of KS development64

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree