Issues, Considerations, and Outcomes in Bilateral Breast Reconstruction

Elisabeth K. Beahm

Robert L. Walton

Introduction

Each year over 40,000 women die from breast cancer in the United States alone, with an estimated lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of approximately 13% (1). The BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation confers a risk estimated to be as high as 87% for developing breast cancer by the age of 70 years (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Although predominantly a unilateral disease, the contralateral breast is at increased risk in patients with breast cancer, and especially in those with genetic markers. The application of bilateral mastectomy, a procedure that may include contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) or bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (BPM), as a risk-reducing procedure has been carefully and convincingly studied. Prophylactic mastectomy has a demonstrated cancer risk reduction of more than 80%, underscoring a significant increase in the application of BPM and CPM procedures in the United States (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Indications for these procedures continue to evolve (9). In BRCA patients, the benefit of mastectomy has been shown to be greater in younger patients, in those with a high-penetrance mutation, and in patients with node-negative disease, conferring an increased survival of 0.6 to 2.1 years (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). From the clinical perspective, 6 normal breasts must be removed in high-risk patients to avert 1 case of breast cancer, and 25 normal breasts must be removed to prevent a single death from breast cancer. In moderate-risk patients, the numbers of mastectomies nearly doubles for each category (2,3,4,5,6,7,8).

The increased application of prophylactic mastectomy must be considered in terms of the positive and negative impacts of any associated reconstructive procedures that may follow. Surgical complications in reconstructive surgery can and do occur and unfortunately are linked to poor patient satisfaction (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44). In the case of prophylactic mastectomy, complications appear to occur with the same general frequency in the preventative breast as in the index breast (5,6,26).

Bilateral Versus Unilateral Breast Reconstruction: the Surgical Decision Process

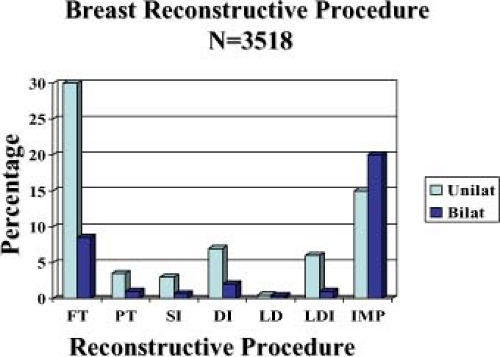

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center, the number of bilateral breast reconstructions performed after 2000 has increased by approximately 36%. We have noticed a differential utilization of reconstructive strategy in the bilateral reconstructions. Analysis of 1,590 consecutive cases of immediate breast reconstruction from July 2000 to July 2005 demonstrated 1,200 cases of unilateral and 390 cases of bilateral reconstruction. Over two thirds (68%; 816 cases) of the unilateral cases were managed with autologous tissue, while 32% (384 cases) were implant-based reconstructions. The reverse was noted in the bilateral patients. In this setting, implants were utilized in 62% (242 cases), while autologous tissues were utilized for reconstruction in 38% (148 cases) (Fig. 71.1).

The trend to treat bilateral mastectomy deformities with implants compared to treating unilateral deformities with autologous tissue did not evolve by chance (45,46,47,48). While the surgical objectives of aesthetics in form and symmetry are the same for both autologous and implant-based breast reconstructions, the surgical effort is not (49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83). From the surgeon’s perspective, bilateral breast reconstruction doubles the surgical energy required for management (84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95). This is compounded by the fact that insurance payments for professional services rendered for performing implant-based reconstructions are nearly equal to those received for autologous reconstructions despite the large disparities between the two modes in work effort and operating time (27,28,29,30,31,32). Therefore, the decision to proceed with one type of reconstruction over another may well be influenced by the rate of reimbursement for time and energy expended in the reconstructive effort.

Other confounding issues may also impact the surgical decision process (33,44,47,48). Autologous tissue affords a soft, warm, permanent, and potentially sensate breast replacement (33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83). Bilateral autologous breast reconstruction can give gratifying results yet may be inappropriate or impossible in certain settings. The extremes of weight pose problems in the morbidity and/or availability of donor sites (34,35,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48). Donor-site morbidity can be proffered as a legitimate argument against autologous approaches, especially for abdominal-based flaps, in which the risks of pain, contour deformity, and hernia are considerably higher in the bilateral than in the unilateral setting, even with the use of perforator or muscle-sparing flaps (41,42,43,44,48,51,52,83,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107). While possibly yielding extraordinary results, bilateral autologous breast reconstruction is a challenging endeavor for both patient and surgeon.

The cumulative effect of the foregoing factors drives the decision-making process in reconstructive technique and accounts for the disparity in approach to unilateral compared to bilateral breast reconstructions.

Implant-Based Breast Reconstructions

Implant-based breast reconstruction remains the most commonly performed type of breast reconstruction both nationally and internationally (84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95). This approach is appealing, as implants completely obviate the need for a donor site, are perceived as “less invasive” than autologous flaps, and require a shorter convalescence. Many patients simply do not want to undergo lengthy and/or staged autologous procedures. Implant-based reconstructions may also be favored in situations

with a marginal or insufficient volume of available abdominal tissue. This is particularly pertinent for younger patients, who are more likely to be undertaking risk-reducing mastectomy (6,10,13,14,15,16,17,19,26,85,90,91,92). Incurring less operative time, as noted earlier, implants provide comparable reimbursement to autologous flaps.

with a marginal or insufficient volume of available abdominal tissue. This is particularly pertinent for younger patients, who are more likely to be undertaking risk-reducing mastectomy (6,10,13,14,15,16,17,19,26,85,90,91,92). Incurring less operative time, as noted earlier, implants provide comparable reimbursement to autologous flaps.

There are several approaches to implant-based breast reconstruction (84,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,93). Most commonly, a “two-stage” approach is employed, with use of a tissue expander followed by a secondary procedure for expander removal and placement of a permanent implant (Fig. 71.2). Less frequently, a postoperatively adjustable implant may be used in lieu of an expander, inserted at the time of mastectomy and sequentially inflated from a remote port. The port is then removed, leaving the permanent implant in place. While appealing, this approach is less often employed, as there is a relatively limited range of implant sizes and shapes and a higher rupture rate in these devices.

Insertion of a fully inflated permanent implant at the time of mastectomy has been advocated to preserve the breast volume and skin envelope and minimize the time lag and operative steps required to achieve the reconstructive endpoint. This latter approach has been increasingly utilized in the application of bilateral nipple-areolar (NAC)–sparing mastectomies (87,88). While a more expeditious approach to the reconstructive process is appealing, the rationale for employing staged expansion of the mastectomy skin envelope largely stems from concerns about the viability of the mastectomy skin flaps, which have a 3.5% rate of necrosis (6). The placement of a partially deflated expander minimizes the potential for exacerbating a compromised flap and has the secondary benefit of permitting adjustment in the case of an unfavorable pathology report and need for radiation and so on (85,90,93) (Fig. 71.3). The use of acellular dermis and bioprosthetic materials to extend the pectoralis muscle and improve initial expander and implant fill has been increasingly employed in this regard (92).

Major concerns about implant-based reconstructions include the stability of the prosthesis over time and the development of fibrous capsular contracture around the implant. Short-term complication rates are significantly lower in implant-based reconstructions. The long-term (>5 years) loss rate of implants, additional revision, and complication rates reflect on the temporal instability of implants over time (29,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,84,85,86,90,95). It is important to emphasize the long-term limitations of implants to patients, and particularly the younger patients, who will likely undergo sequential long-term operative revisions of their reconstructed breasts (29,32,33,34,36,37,38,39) (Fig. 71.4).

Latissimus Dorsi Breast Reconstruction

The latissimus muscle or musculocutaneous flap is used primarily for breast reconstruction in patients who are not candidates for an abdominal or other remote flap. It has been used to great advantage in implant-based breast reconstructions that require additional soft tissue for coverage (74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83). The additional soft tissue coverage provided by the latissimus muscle over the implant significantly improves the appearance and shape of the reconstructed breast and provides for improved protection, as well as additional fill for the superior medial pole, infraclavicular hollow, and axilla. The application of the latissimus flap also appears to provide for improved long-term retention of a prosthesis. The disadvantages of the latissimus flap include persistent seroma at the donor site, unfavorable scarring, alteration of the contour of the back, and functional deficits secondary to latissimus muscle harvest (81,82,83). In the bilateral setting, a major drawback is the necessity for intraoperative change in the patient’s position, which results in a lengthy, cumbersome operative procedure. As the latissimus is generally used in conjunction with an implant, the reconstruction carries the potential for implant rupture and fibrous capsular contracture, which may also constitute a significant disadvantage.

The technical refinements and variables of latissimus flap harvest and inset include denervation of the nerve and/or complete takedown of the humeral insertion of the flap to limit undesirable postoperative contraction of the muscle, which distorts the contour of the breast, placement of a permanent, postoperatively adjustable implant or a tissue expander, and the degree to which the pectoralis major muscle is elevated. All of the foregoing technical refinements may lead to improved outcomes, but results vary from surgeon to surgeon (74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83). In addition, the orientation and size of the donor-site scar on the back is quite variable and will be dictated by the size and location of the mastectomy skin defect (78,79) (Fig. 71.5). Ideally, many surgeons prefer placement of the scar in the bra line to conceal its appearance when the patient is wearing a bathing suit or other revealing attire.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree