Invasive Carcinoma: Radiation Therapy After Mastectomy

Jefferson E.C. Moulds

Introduction

Adjuvant radiotherapy after mastectomy reduces the risk of tumor recurrence in the chest wall and regional lymphatic areas by a factor of about two thirds. This risk reduction for locoregional recurrence is highly statistically significant and remarkably consistent in more than 30 randomized trials involving more than 16,000 women conducted over the last five decades (1,2) and is independent of risk of local recurrence, type of mastectomy, and technique of radiotherapy.

Effect of Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy on Overall Survival

Despite the clear and dramatic effect of radiotherapy on locoregional recurrence (Fig. 20.1), the impact on overall survival has been difficult to demonstrate until recently. Various theories on the importance of local therapy have waxed and waned over the last century. Earlier emphasis on aggressive local treatment as expressed by Halsted (3) gave way to a focus on the systemic nature of the disease as articulated by Fisher and others (4). Current opinion has evolved to appreciate the view of Hellman that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and that inadequate local therapy may leave persistent subclinical locoregional disease that in some cases may give rise to distant metastases (5).

There are several reasons why, after so many trials involving so many patients, the impact of local therapy on overall survival was so difficult and took so long to demonstrate. First, the impact on survival is fairly modest compared to that on local-regional recurrence. It is seen only after many years, whereas the benefit on local-regional recurrence is seen quickly, as is the benefit on survival from systemic therapies. Second, toxicity, particularly cardiac toxicity from older radiotherapy techniques, adversely affected overall survival, partially counteracting the benefit obtained in breast cancer–specific survival. Many of the early trials included patients with favorable node-negative cancers who were unlikely to benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy at all.

Determining the group that benefits the most from radiotherapy is contentious. The addition of radiotherapy only could have an impact on distant metastases if a particular patient had occult locoregional disease after mastectomy that was completely eradicated by radiotherapy and that patient did not have subclinical distant metastases at time of diagnosis that were unable to be eradicated by adjuvant systemic therapy. This implies that the group most likely to obtain a survival benefit from postmastectomy radiotherapy might be at some intermediate risk for local recurrence. If the risk for local recurrence is quite low, then the absolute benefit from radiotherapy would be quite small. If the risk for local recurrence is very high, then the risk of undetected but already established and ultimately uncontrollable distant disease is high as well, and the impact of local measures on survival should be minimal. Of interest, as the ability of systemic therapy to eradicate metastatic disease improves, it is possible that a larger group of patients could see a survival benefit from radiotherapy. Of course, if systemic therapy were able to eradicate all disease completely, there would be no need for radiotherapy or surgery. It is unlikely that such systemic therapy will be developed for solid tumors such as breast cancer, although it should be acknowledged that chemotherapy and endocrine therapies do have a favorable impact on local control (6), although not as much as radiotherapy (7,8).

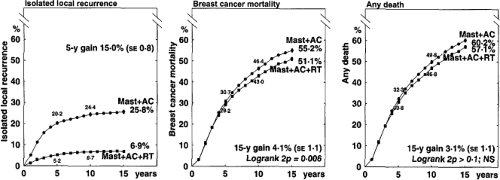

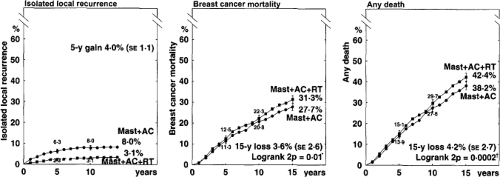

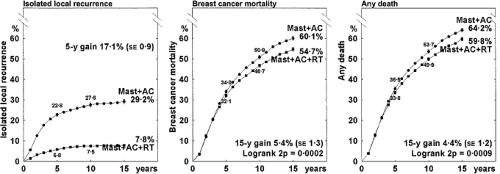

The potential for late cardiac morbidity from radiotherapy is well established (9,10,11,12,13). The Oxford meta-analysis obtained updated individual patient data from all randomized trials (published and unpublished) and evaluated the addition of radiotherapy after potentially curative surgery for breast cancer. This systematic review demonstrated a modest increase in breast cancer–specific survival at 20 years of 4.1% (2p = 0.006) and a decrease in non–breast cancer–specific survival, resulting in an absolute benefit from radiotherapy of 3.1% that does not reach the conventional level of statistical significance (2p >0.1) (Fig. 20.1). Node-negative patients, for whom the absolute local-regional control benefit of postmastectomy radiotherapy is low, appear to experience a deleterious effect on overall survival (Fig. 20.2). For node-positive patients, the 17.1% reduction in local-regional recurrence at 15 years translates into an overall survival benefit of 4.4%, which is statistically significant (2p = 0.0009) (Fig. 20.3).

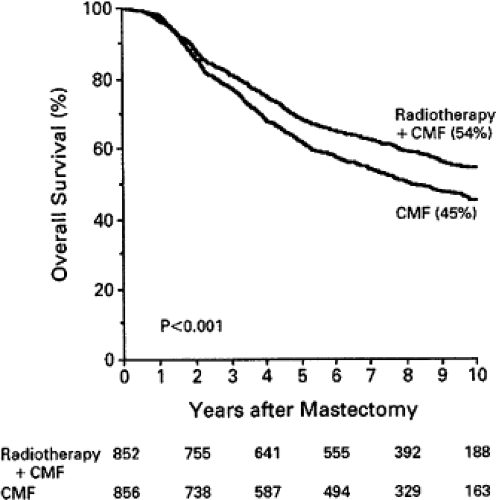

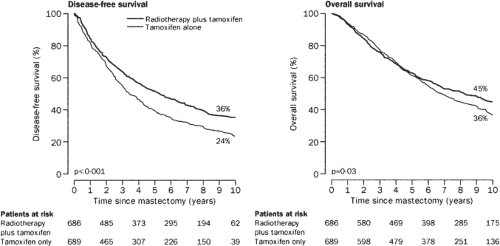

Most of the individual randomized trials of postmastectomy radiotherapy were small and insufficiently powered, did not utilize adjuvant systemic therapy, and treated considerable cardiac volume to high doses of radiation, and many did not treat the areas at greatest risk adequately. As a result, they would not be expected to show a survival benefit from radiotherapy. The most recent trials of postmastectomy radiation do show a survival benefit. The Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) randomized 3,083 women with stage II or III breast cancer. The 1,708 premenopausal patients received eight cycles of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) plus irradiation versus nine cycles of CMF alone. The 1,375 postmenopausal women all received tamoxifen. Meticulous radiation technique was used to treat the chest wall, supraclavicular, and internal mammary nodal areas while minimizing exposure to the heart. Comprehensive axillary radiation was delivered to select patients. At 10 years there was a 9% survival advantage in the group receiving radiotherapy (14,15) (Figs. 20.4 and 20.5). In premenopausal patients, survival was improved, 54% versus 45% (p <0.001). For postmenopausal patients survival was improved, 45% versus 36% (p = 0.03). There was no suggestion of an increase in ischemic heart disease for

those randomized to radiotherapy or in patients receiving radiotherapy for left-sided tumors compared to those with right-sided tumors (16). The British Columbia trial randomized 318 premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with mastectomy and CMF chemotherapy. With 15 years of follow-up, overall survival differed by nearly the same amount as in the Danish Trials, 54% versus 46% (p = 0.07) (17). By 17 years this difference had reached the customary level of statistical difference, p = 0.02 (18).

those randomized to radiotherapy or in patients receiving radiotherapy for left-sided tumors compared to those with right-sided tumors (16). The British Columbia trial randomized 318 premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with mastectomy and CMF chemotherapy. With 15 years of follow-up, overall survival differed by nearly the same amount as in the Danish Trials, 54% versus 46% (p = 0.07) (17). By 17 years this difference had reached the customary level of statistical difference, p = 0.02 (18).

Criticism of the Danish Trials of Postmastectomy Radiation

The Danish trials have been subjected to criticism over the high rate of local failure and the limited extent of surgery, as well the dated systemic therapy, and thus their applicability to current treatment decision making in the United States has been questioned. A median of only seven axillary nodes was identified, and 255 patients had fewer than four nodes recovered. The chemotherapy was not “classic” CMF and certainly was not as aggressive as modern regimens that include an anthracycline, a taxane, appropriate endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab when applicable. The concern over these trials is that if surgery (and systemic therapy) had been more like the current practice in the United States, the benefit from radiation might have been considerably smaller and not worth the toxicity in all groups. Even if this argument were correct, it still acknowledges that local therapies can affect survival, which is a fundamental change from a strict interpretation of the systemic theory of breast cancer.

Which Patients Should Receive Adjuvant Radiation After Mastectomy?

Consensus in the United States has emerged that patients at high risk for local failure should receive postmastectomy radiation therapy in order to reduce the risk of local failure (19,20,21).

While some locoregional recurrences are salvageable, it appears that early adjuvant radiotherapy does reduce the risk of ultimately uncontrollable local disease or “local shambles” compared to later salvage local measures (22). Without radiotherapy, patients treated with modern chemotherapy who have four or more positive axillary nodes have a rate of locoregional failure as a first site of recurrence of at least 19%, and this increases dramatically with increasing tumor size (23,24,25,26). Furthermore, the ultimate cumulative rate of locoregional recurrence is considerably greater and rarely reported. Patients with primary tumors larger than 5 cm are at similarly high risk of locoregional recurrence and generally should receive radiation.

While some locoregional recurrences are salvageable, it appears that early adjuvant radiotherapy does reduce the risk of ultimately uncontrollable local disease or “local shambles” compared to later salvage local measures (22). Without radiotherapy, patients treated with modern chemotherapy who have four or more positive axillary nodes have a rate of locoregional failure as a first site of recurrence of at least 19%, and this increases dramatically with increasing tumor size (23,24,25,26). Furthermore, the ultimate cumulative rate of locoregional recurrence is considerably greater and rarely reported. Patients with primary tumors larger than 5 cm are at similarly high risk of locoregional recurrence and generally should receive radiation.

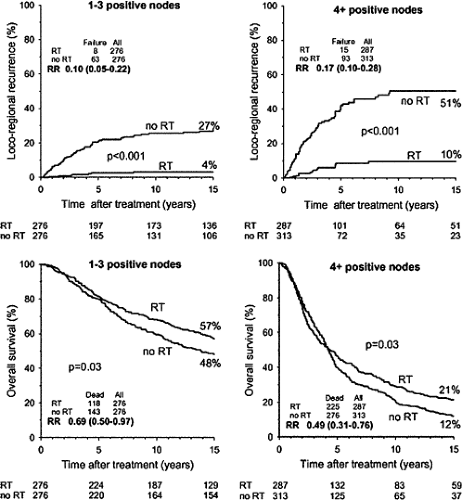

There is little consensus for patients at intermediate risk of local recurrence. A randomized U.S. Intergroup trial of postmastectomy radiation for patients with one to three positive axillary nodes and tumors smaller than 5 cm closed due to poor accrual. The U.K. Medical Research Council recently activated the Selective Use of Postoperative Radiotherapy after Mastectomy (SUPREMO) trial, which enrolls patients with one to three positive nodes after mastectomy or node-negative patients with tumors larger than 2 cm with either grade III histology or lymphovascular space invasion. The primary endpoint is overall survival, so it should be at least a decade before meaningful data are available. Analysis of the 1,152 patients in the Danish trials who had eight or more axillary nodes removed (a surrogate marker for adequate surgery) suggests that those with one to three positive axillary nodes received the same 9% benefit in overall survival from radiation as those with four or more involved nodes in spite of experiencing a smaller absolute benefit in locoregional control (27) (Fig. 20.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree