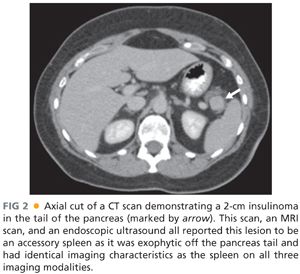

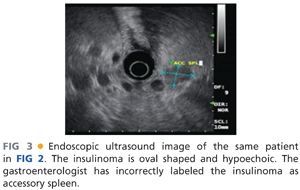

■ Since the early 1990s, a variety of institutions with large experience in insulinoma have used endoscopic ultrasound as the primary imaging technique.12,13 Endoscopic ultrasound allows for direct imaging in three dimensions with very close field ultrasonography of the head, neck, and uncinate process. The pancreatic body is less well imaged as it can only be seen from the placement of the ultrasound probe within the stomach and depending on the patient’s body habitus, the tail may be a blind zone for endoscopic ultrasound. The ultrasound appearance of insulinoma is an oval hypoechoic mass with well-defined margins (FIG 3). Endoscopic ultrasound also allows a relatively straightforward fine needle aspiration biopsy, which would produce neuroendocrine cells on cytology to confirm the diagnosis. Positive imaging may occur with identification of peripancreatic lymph nodes that are often embedded on the surface of the pancreas or accessory spleen, which can be found on the surface or actually within the parenchyma of the pancreas primarily in the tail region. Standard fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans have been shown to be of limited value in insulinomas as these may not be particularly hypermetabolic lesions.14 A recent report showed a specific targeting agent of indium-labeled glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor that was sensitive for insulinomas and also could allow the use of a handheld intraoperative probe to detect these lesions.15 This technique is being developed in Switzerland and has not been widely adapted elsewhere.

■ Despite the high sensitivity of cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic ultrasound, a portion of patients with well-documented biochemical insulinoma may have no lesions imaged.16,17 Historically, an interventional radiology invasive procedure called portal venous sampling was used in which a transhepatic portal vein cannulation was performed and blood was drawn from various regions and tributaries from the portal vein and assayed for insulin.18,19 Portal venous sampling has now been replaced by intraarterial calcium stimulation with hepatic vein sampling. In this technique, two catheters are placed: one in the right hepatic vein and a second standard arterial angiogram catheter advanced into arterial branches feeding the pancreas. Calcium is injected into branches of the splenic artery supplying the body or tail or branches of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery off the gastroduodenal artery or the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery off the superior mesenteric artery. Blood is drawn from the right hepatic vein at 0 second, 30 seconds, and 60 seconds after calcium infusion and an increased gradient of greater than twofold in the hepatic vein insulin levels is significant.18 This procedure does not image insulinoma but rather identifies the region of production of insulin. It is a highly specific test and may be helpful in focusing efforts in the operating room to one area or the other. It may justify performance of a blind distal pancreatectomy for patients without imaged lesions that have gradient in the body and tail, but a blind pancreaticoduodenectomy is virtually never indicated.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ The choices for nonoperative management include diet modification or hypoglycemic agents. One approach for management of hypoglycemic symptoms is small frequent meals, particularly of slowly absorbed carbohydrates to provide more of a steady level particularly while patients are sleeping.2,5 Diazoxide is a benzothiazide analog with antihypertensive effects but also with potent hyperglycemic effects. It inhibits insulin release from the beta cells and enhances glycogenolysis to also contribute to elevation of blood sugar. Side effects include sodium retention causing edema and some patients have nausea. A second agent that has been used for control of hypoglycemic symptoms in insulinoma is somatostatin analogs. However, due to relatively low expression of somatostatin receptors on most well-differentiated insulinomas, these have not been markedly effective.

TECHNIQUES

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

■ The cornerstone to performing an insulinoma resection is being absolutely certain the patient has the disease proven by definitive biochemical workup. In patients who have imaged lesions, particularly if they are biopsied as neuroendocrine tumors or have classic appearance on CT or MRI, this provides very good evidence that the patient has the disease. In patients who have no definitive imaging of the site of the lesion, the surgeon has to review in detail the preoperative blood chemistries. This analysis includes reviewing the data related to a 72-hour fast, looking at concurrent glucose, insulin, and proinsulin levels as described earlier.

■ It is very important for patients to either be the first case of the day or to be admitted to the hospital and have dextrose solution running so that they do not suffer from severe hypoglycemia while they are nil per os (NPO) prior to general anesthesia. In general, for abdominal procedures, anesthesiologists do not administer glucose-containing fluids as they are infused at a relatively rapid rate and patients are catabolic. When operating on patients with insulinoma, it is very important to communicate to the anesthesia team that dextrose needs to be administered often and frequent analysis of glucose levels need to be performed.

SURGICAL APPROACH AND PATIENT POSITIONING

■ Over the past few decades, the majority of patients in most surgical series have been treated with an open surgical technique. There have been many recent reports of laparoscopic excision of insulinomas, particularly in the body and tail, with high success rate. We will describe primarily identification and resection of insulinomas using an open technique and also provide information on laparoscopic approaches.

■ The approach for the open resection of an insulinoma is performed with the patient lying supine with either an upper midline incision or a bilateral subcostal incision. The vast majority of the substance of the pancreas can be assessed with an upper midline incision with the exception of the far distal tail, which may be somewhat difficult particularly in obese patients. For patients with a well-localized insulinoma in the head and neck, uncinate process, or proximal body, a midline incision is preferred if the patient’s body habitus is appropriate. Any patient can be approached with a bilateral subcostal incision.

EXPOSURE OF THE PANCREAS

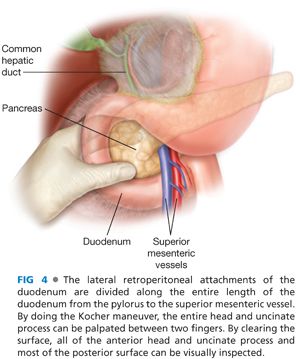

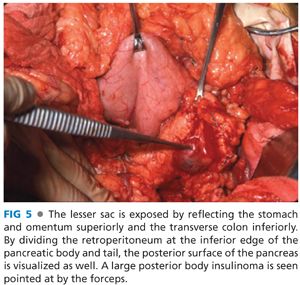

■ The initial steps of an insulinoma resection is to briefly assess the liver, although insulinoma is a benign disease in the vast majority of patients, and if liver metastases existed, they should have been identified on preoperative imaging. The next step is exposure of the pancreas parenchyma. Exposure of the head and neck of the pancreas as well as uncinate process can be achieved with a Kocher maneuver (FIG 4). The duodenum and head of the pancreas are brought up from the retroperitoneal location to allow bimanual palpation for mass lesions as well as visual inspection of both the anterior and posterior surfaces of the pancreatic head. The greater omentum is taken off the transverse colon along its entire length using energy devices with the omentum reflected superiorly, pulling the stomach off the pancreas. There are avascular attachments of the posterior stomach to the anterior pancreas that can be divided sharply. There is always a bridge of vascular tissue from the right gastroepiploic to the middle colic vessels, which crosses anterior to the neck and proximal pancreatic body that needs to be controlled with either energy devices or suture ligation. By dissection along the inferior border of the pancreatic body and tail, the posterior surface can be exposed and the majority of the substance of the pancreatic body and tail can be palpated between two digits (FIG 5). By doing these maneuvers, 95% of the pancreatic parenchyma is accessible for palpation and virtually all of the anterior surface and most of the posterior surface of the body and proximal tail are accessible for visual inspection as well. The only inaccessible area is the very tip of the tail of the pancreas, which may be located completely behind the spleen and require dividing the lateral margins of the splenic ligaments to reflect the spleen medially and expose that area of the very tip of the pancreatic tail.

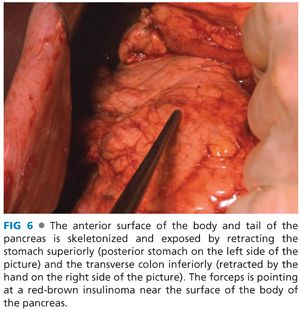

■ Insulinomas are identified by a combination of visual inspection, palpation, and intraoperative ultrasound. Insulinomas are uniformly red-brown in color against the yellow-gray background of the pancreas and lesions near the surface or exophytic lesions can be easily identified by visual inspection (FIG 6). Neuroendocrine tumors have a classic ultrasound appearance and intraoperative ultrasound is a key to management (FIG 7). Even in patients with lesions of the head and uncinate process of the pancreas that are well seen by preoperative endoscopic ultrasound, it is mandatory to have intraoperative ultrasound available. The reason for having intraoperative ultrasound available is because if the small lesion is deep within the parenchyma of the pancreas, it is essential to know exactly where the insulinoma is located so an appropriate enucleation can be performed. It is impossible to use preoperative imaging alone to know where to cut into the pancreas in the same way breast surgeons need intraoperative localizing techniques to remove nonpalpable breast tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree