Nasal injectables and surface treatments alter the appearance of the nose both primarily and following nasal surgery. Fillers such as hyaluronic acids, calcium hydroxyapatite, and fat have a variety of advantages and disadvantages in eliminating small asymmetries postrhinoplasty. All nasal injectables have rare but severe ocular and cerebral ischemic complications. The injection of steroids following nasal reconstruction has a role in preventing supratip swelling and can improve the appearance of grafts to the nose. Resurfacing techniques reduce the appearance of autotransplanted grafts to the nose; there is little controversy about their benefit but surgeon preference for timing is varied.

Key points

- •

All injectable types have been reported to cause rare but serious ocular and cerebral complications; exercise even greater caution following nasal surgery because the altered blood supply may increase risk.

- •

Hyaluronic acid is commonly used to smooth out minor irregularities following nasal surgery; hyaluronidase may be used to minimize the severity of complications. Hyaluronic acid lasts longer in the nose compared with other areas of the face.

- •

Autologous fat is commonly injected into the post-rhinoplasty nasal deformity, particularly when significant volumes are needed.

- •

Steroid injections may be used to reduce edema and scarring following nasal surgery and nasal reconstruction.

- •

Skin resurfacing can improve scars, and is especially useful for full-thickness skin grafts and para-median forehead flaps.

Introduction

The use of injectable fillers has soared over the past 10 years. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons reports an increase from 650,000 filler procedures in 2000 to 2.3 million procedures in 2014. As with many new technologies and medications, increased experience by physicians has led to “pushing the envelope” and using the materials for ever-increasing indications. Before the current era, medical-grade silicone injections had been used for many years to correct thousands of postrhinoplasty deformities with good success; however, the use of this product was not specifically US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the nose, was associated with several complications, and its use was therefore controversial. Safe new injectable biomaterials have fueled the current surge in use, but none of them are FDA approved for the nose. Despite this fact, nonsurgical primary, revision, and reconstructive injectable rhinoplasty has gained popularity. This article discusses the use of injectable fillers in the nose. In addition, it examines the use of autologous fat injections as well as the use of dermabrasion in nasal reconstruction.

Introduction

The use of injectable fillers has soared over the past 10 years. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons reports an increase from 650,000 filler procedures in 2000 to 2.3 million procedures in 2014. As with many new technologies and medications, increased experience by physicians has led to “pushing the envelope” and using the materials for ever-increasing indications. Before the current era, medical-grade silicone injections had been used for many years to correct thousands of postrhinoplasty deformities with good success; however, the use of this product was not specifically US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the nose, was associated with several complications, and its use was therefore controversial. Safe new injectable biomaterials have fueled the current surge in use, but none of them are FDA approved for the nose. Despite this fact, nonsurgical primary, revision, and reconstructive injectable rhinoplasty has gained popularity. This article discusses the use of injectable fillers in the nose. In addition, it examines the use of autologous fat injections as well as the use of dermabrasion in nasal reconstruction.

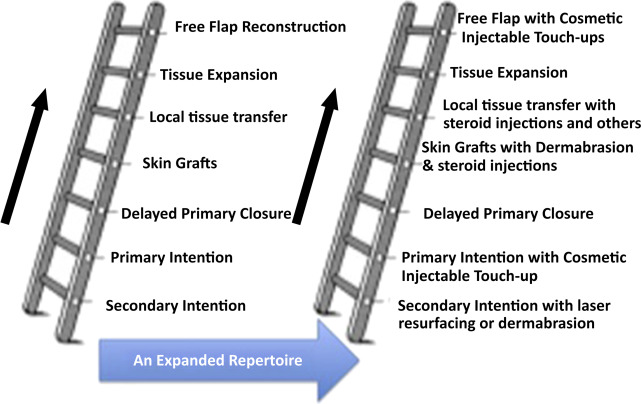

The new reconstructive ladder

The goal of facial and nasal reconstruction is to allow patients to return to their premorbid condition with as little stigma from the deficit as possible. As with every reconstructive situation, strong consideration should be given to the least invasive but appropriate method first, and then clinicians may consider other options from elsewhere on the reconstructive ladder ( Fig. 1 ). Surgery remains the gold standard for safe, long-term correction of nasal abnormalities, both functional and aesthetic. The role of fillers in the nose continues to be explored, and is not considered standard of care for the long-term management of nasal defects. This article presents controversies associated with the use of different types of injectables in the nose, different injection techniques, side effects, complications, and histologic findings.

Overview of nasal injectables

The term nasal injectable in this article is used to mean any substance injected into the nose to physically alter the appearance of the nose. This use differs from medications injected into the nose, such as corticosteroids or botulinum toxin, that alter the healing or functional properties. Table 1 represents a background classification of the basic characteristics and functional properties of injectables, which is essential to understanding the ideal uses of the different injectables.

| G′: elasticity coefficient. Ability to resist deformation from pressure; higher indicates more lift with less volume | — | N′: viscosity coefficient. Ability to resist sheering forces; less diffusion into tissue |

| High G′ and high N′ | Medium G′ and N′ | Low G′ and N′ |

| CaHA: Radiesse | CaHA with lidocaine and HA: Restylane, Perlane, Restylane SubQ, Restylane Lyft | HA: Juvederm Ultra, Juvederm Ultra Plus, Juvederm Voluma, Belotero Balance |

| Less diffusion; precise sculpting | — | More diffusion; improved blending |

| Less volume needed for lift | — | More volume needed for lift |

Injectable fillers

Hyaluronic Acids: Restylane, Juvaderm, Belotero

Hyaluronic acid (HA) products (Restylane, Juvaderm, Belotero, and others) have been used as adjuncts following rhinoplasty or nasal reconstruction to adjust minor deformities. In addition, they have been used as stand-alone tools for primary injectable rhinoplasty and nasal reconstruction. The most commonly reported applications of HA fillers include the correction of tip ptosis, dorsal irregularities, dorsal hump camouflage, and saddle deformity. These irregularities may occur as a result of prior trauma or genetic predisposition, or may be iatrogenic following nasal surgery.

To address a drooping, ptotic nasal tip, which is commonly seen in Asian women, Han and colleagues described multiple injections at the supraperiosteal, supraperichondrial, intramuscular, and subcutaneous layers. Layering the HA in multiple planes was thought to prevent the dorsal widening that can be seen with supraperiosteal injections alone. In addition, the investigators speculated that the use of both sharp needles and blunt cannulas may help minimize the risk of intravascular injection in higher-risk vascular regions. Han and colleagues used EME (Love II), a different HA than is used in the United States and that requires the use of larger gauge needles and cannulas as it is more viscous, has a higher N′, and contains more HA per milliliter relative to Restylane and Juvaderm. In their series of 280 patients, there are no reports of skin necrosis or ocular complications.

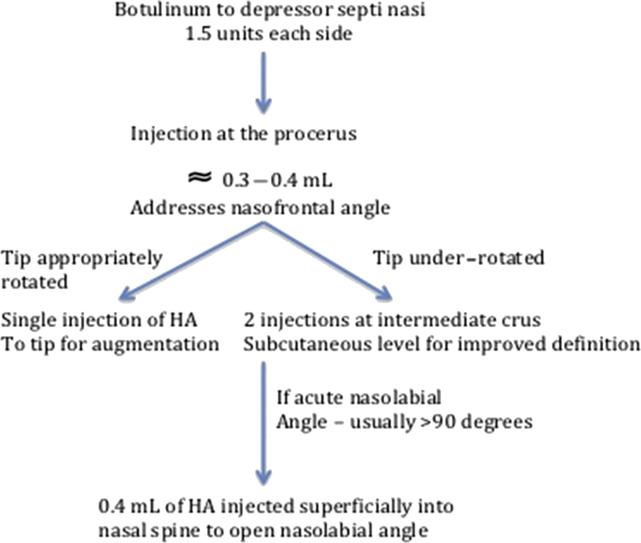

Redaelli addresses the drooping tip with a combination of HA and botulinum toxin injections ( Fig. 2 ). Botulinum toxin type A (1.5 units of Vistabex) was injected into each depressor septi nasalis muscle in 45% of the reported patients. Preventing motion of the depressor septi muscle limits the nose’s tendency to droop with smiling and perioral animation, and provides a stable platform for HA layering. Depending on the extent to which the nose drooped, injections were performed in a stepwise sequence. Ninety-five patients are presented in the series and no significant complications were encountered. These principals of injection rhinoplasty can also be applied to the reconstructed nose; however, care must be taken to avoid intravascular or pressure ischemia–induced necrosis caused by the altered and less predictable blood supply patterns.

The literature contains many reports of injectables used in the nose, but not every article should be accepted as evidence for safe or appropriate clinical practice. Liapakis and colleagues report that HA can provide aesthetic improvements in postrhinoplasty patients for the temporary postrhinoplasty defects caused by asymmetrical soft tissue edema. Eleven patients were seen 1 month following standard surgical rhinoplasty for asymmetry that was presumed to be associated with asymmetrical postoperative soft tissue edema. A variety of injectable techniques were used to insert Juvederm into the nose to correct the asymmetrical edema. No complications were reported, but 7 of the 11 patients required secondary HA injections within 2 weeks to correct residual deformities. Despite the reported success of this publication, the idea of injecting the nose at such an early postoperative period must be seriously questioned. Clearly, following rhinoplasty, edema may persist for a year or more. Variations in the amount and location of edema in the early and even later postoperative periods may be caused by something as simple as the patient’s sleeping position, and is not likely to alter a well-constructed nose’s long-term symmetry. At the same time, the long-term effects of healing and persistent edema that may be induced by filler injection at 1 month following surgery are unknown and may themselves cause long-term asymmetries and complications. The suggestion of filling the nose with an HA product to create postoperative symmetry at 1 month after surgery should be seriously doubted as a reasonable approach, and the authors warn against incorporating this as a standard practice.

The use of HA in the treatment of saddle nose deformity is a useful technique that can provide patients with improved cosmetic appearance in place of, or preceding, definitive surgical nasal reconstruction. Bennett and Reilly present a case of Restylane injection to correct a significant saddle nose deformity in a 22-year old woman with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, who was shown to have continued improvement in appearance at 6 months postoperatively. They point out that this patient will also have an improved appreciation of what to expect following definitive surgical reconstruction. Vogt and colleagues report 4 cases of successful 42-month mean follow-up after definitive surgical nasal reconstruction of saddle nose deformity with an L-shaped cartilage rib graft. These patients were in remission from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (ANCA-associated vasculitis) at the time of surgical rhinoplasty, but they were continuing to receive immunosuppressive medication. Although the data are limited, it is suggested that patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis with saddle nose deformity can undergo cosmetic nasal filler during active disease states with temporizing injectable fillers, and once in remission they may safely undergo definitive surgical repair.

Calcium Hydroxyapatite: Radiesse

Significant controversy exists regarding calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHA) in nasal reconstruction and to a lesser degree as a form of injection rhinoplasty. Postrhinoplasty, CaHA offers a longer duration; its effects can be expected to last 12 to 18 months compared with 6 to 12 months with HA products. Stupak and colleagues reported their experience with 13 patients. At least 3 months following rhinoplasty or trauma, Radiesse was injected to treat sidewall depressions, overly deep supratip breaks, alar asymmetries, and dorsal irregularities. Injections were performed with 27-gauge and 30-gauge needles and patients were evaluated for appearance, complications, and pain. Fifteen of 17 injection sites were graded as improved; 8 of 13 patients considered their outcome excellent, with 2 patients considering their outcome good. There was 1 minor complication of self-limiting dorsal erythema. Pain was tolerable for all patients. This series suggests that the feasibility and outcomes of CaHA nasal augmentation are similar to what has been presented with fat and HA.

In contrast, Kurkjian and colleagues discourage CaHA use for primary injection rhinoplasty and for secondary nasal reconstruction. The arguments against CaHA are 3-fold: clinicians cannot correct injection imperfections because of a lack of an equivalent hyaluronidase analog, HA products can last up to 2 to 3 years in the nose (not inferior to CaHA), and thin nasal skin can lead to palpable nodularity. These same principles are magnified in postrhinoplasty patients with the added caveat that the blood supply to the skin is fundamentally compromised and so the risk of irreparable complication is increased. There is limited clinical evidence to suggest that CaHA presents a higher risk of complication with injectable rhinoplasty. Bernd Schuster reports on 46 patients (26 undergoing CaHA injections and 20 undergoing HA injections) with 88 treated areas, with 6 patients experiencing complications, all of whom were treated with CaHA. Mild complications included 2 visible hematomas and palpable subcutaneous nodules. Moderate complications included an erythematous nasal tip, treated effectively with topical steroids and cefuroxime. Serious complications included extensive facial cellulitis, and, in a postrhinoplasty patient, a displaced Medpor implant, nasal tip abscess, and skin necrosis. The abscess was drained and the implant repositioned. Given these complications, Dr. Schuster no longer performs CaHA injection rhinoplasty. CaHA is a controversial injectable material to use following nasal reconstruction. Surgeons should be aware of the risks, and exercise their best judgment to ensure optimal results.

Autologous fat

Autologous fat transfer can be used as a stand-alone nasal augmentation procedure or as a touch-up following nasal reconstruction or rhinoplasty. The donor site should be easily camouflaged and highly lipogenic, with common sites including the abdomen or outer thighs in women and the flanks in men. Fat harvest is achieved through a small incision with a 3-mm suction cannula and 10-mL syringe for suction. The aspirated fat is centrifuged and prepared for injection. Some practitioners freeze the remaining fat, store it in personal freezers, and then thaw it for subsequent injections. This practice is not standard and should cease, because the storage of any part of a human body in a non–tissue bank setting should be avoided because of disease transmission, other health-related factors, and legal implications. Various injection techniques are listed in Table 2 .

| Injection Equipment | Injection Plane | Injection Technique | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baptista et al, 2013: 20 postrhinoplasty | 21-gauge needle then 21-gauge cannula | At the periosteum and in the SMAS | Cross-hatched layers |

| Cardenas & Carvajal, 2007: 78 at rhinoplasty | Via 5-mm incisions as closing rhinoplasty | Subcutaneous, onto bone and cartilage grafts | Directly onto structures of nose |

| Monreal, 2011: 15 at rhinoplasty, 18 postrhinoplasty | 1.2–1.4-mm blunt-tip cannulas; 18-gauge needles for adherent or fibrous tissues | In the SMAS and subcutaneous planes | Direct injection without cross-hatching |

| Erol, 2014 : 313 no rhinoplasty | 22–24-gauge cannula | Intradermal or subcutaneous | Directly on to deformities |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree