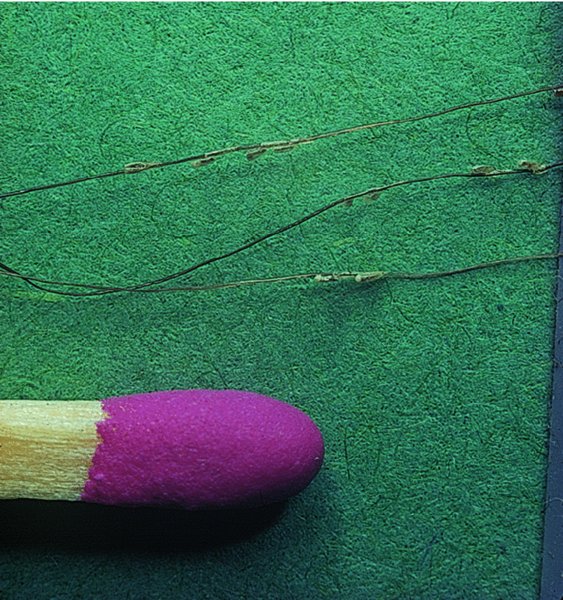

17 Infestation, the presence of animal parasites on or in the body, is common in tropical countries and less so in temperate ones. Infestations fall into two main groups: Table 17.1 lists some of the ways in which arthropods affect the skin. Only a few can be discussed here. Table 17.1 Arthropods and their effects on the skin. Lice are flattened wingless insects that suck blood. Their eggs, attached to hairs or clothing, are known as nits. The main feature of all lice infestations is severe itching, followed by scratching and secondary infection. Two species are obligate parasites in humans: Pediculus humanus (with its two varieties P. humanus capitis, the head louse, and P. humanus corporis, the body louse) and Phthirus pubis (the pubic louse). Head lice are still common: up to 10% of children have them (Figure 17.1), even in the smartest schools. Many of these children have few or no symptoms. Infestations peak between the ages of 4 and 11, and are more common in girls than boys. A typical infested scalp will carry about 10 adult lice, which measure some 1–3 mm in length and are greyish, and often rather hard to find. An adult female louse lives for about 1 month and during that time lays 5–10 eggs per day. These egg cases (nits) can be seen easily enough, firmly stuck to the hair shafts. Spread from person to person is achieved by head-to-head contact, and perhaps by shared combs or hats. Figure 17.1 This woman had acquired a head louse infection from her grandchild. The main symptom is itching, although this may take several months to develop after the first infestation. Subsequent infestations produce itching more rapidly, suggesting that this is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. At first the itching is mainly around the sides and back of the scalp; later it spreads generally over the scalp. Scratching and secondary infection soon follow and, in heavy infestations, the hair becomes matted and smelly. Draining lymph nodes often enlarge. Secondary bacterial infection may be severe enough to make the child listless and feverish. All patients with recurrent impetigo or crusted eczema on their scalps should be carefully examined for the presence of nits. None are usually required. The finding of living moving lice means that the infestation is current and active, and needs treatment. Empty egg cases signify only that there has been an infestation in the past, but suggest the need for periodic re-inspection. Dimeticone is a non-neurotoxic agent that coats the lice and probably suffocates them. It is rubbed into dry hair and scalp and left for 8 hours.This is then repeated 1 week later. Cure rates of 70% or more are reported and it is non-irritant and well tolerated. Malathion and the synthetic pyrethroid permethrin have traditionally been used, but resistance to these neurotoxic pediculocides has been increasing since the 1990s. Sensitivity of less than 20% is reported in some areas, and resistance to more than one agent is also developing. Unsurprisingly, this has been accompanied by a big rise in infestation rates. Where resistance is not yet a problem these agents are more effective at killing adult lice and nymphs than eggs and should thus be applied on two occasions, 1 week apart. The second application is needed to kill young nymphs that hatch after the first application, usually 6–10 days after being laid. Lotions should remain on the scalp for at least 12 hours, and are more effective than shampoos. Wet combing with a fine toothed comb every 3 days for 14 days is an alternative to the treatments mentioned above. The technique relies on physical removal of lice and eggs and is more effective than treatment with neurotoxic agents if carried out thoroughly. Shampoo or conditioner acts as a lubricant and helps with combing, but occasionally matting is so severe that the hair has to be clipped short. A systemic antibiotic may be needed to deal with severe secondary infection. Pillow cases, towels, hats and scarves should be laundered or dry cleaned. Other members of the family and school mates should be checked. Systemic ivermectin therapy is reserved for infestations resisting the treatments listed above. Body lice have diverged genetically from head lice. This probably occurred between 85 000 and 170 000 years ago, and marks the time at which anatomically modern humans started wearing clothes. Body louse infestations are now uncommon except in the unhygienic and socially deprived. Epidemics also occur in times of social disruption, such as civil war or in refugee camps. Morphologically, the body louse looks just like the head louse, but lays its eggs in the seams of clothing in contact with the skin. Transmission is via infested bedding or clothing. Self-neglect is usually obvious; against this background there is severe and widespread itching, especially on the trunk. The bites themselves are soon obscured by excoriations and crusts of dried blood or serum. In chronic untreated cases (‘vagabond’s disease’), the skin becomes generally thickened, eczematized and pigmented; lymphadenopathy is common. Body lice can act as vectors for the organisms causing epidemic typhus, relapsing fever and trench fever. In scabies, characteristic burrows are seen (p. 253). Other causes of chronic itchy erythroderma include eczema and lymphomas, but these are ruled out by the finding of lice and nits. Clothing should be examined for the presence of eggs in the inner seams. First and foremost treat the infested clothing and bedding. Lice and their eggs can be killed by high temperature laundering, by dry cleaning and by tumble-drying. Less competent patients will need help here. Once this has been achieved, 5% permethrin cream rinse or 1% lindane lotion (United States only; Formulary 1, p. 405) may be used on the patient’s skin. Pubic lice (crabs) are broader than scalp and body lice, and their second and third pairs of legs are well adapted to cling on to hair. They are usually spread by sexual contact, and most commonly infest young adults. Severe itching in the pubic area is followed by eczematization and secondary infection. Among the excoriations will be seen small blue–grey macules of altered blood at the site of bites. The shiny translucent nits are less obvious than those of head lice (Figure 17.2). Pubic lice spread most extensively in hairy males and may even affect the eyelashes. Figure 17.2 Pediculosis pubis. Numerous eggs (nits) can be seen on the plucked pubic hairs. Eczema of the pubic area gives similar symptoms but lice and nits are not seen. The possibility of coexisting sexually transmitted diseases should be kept in mind. Carbaryl, permethrin and malathion are all effective treatments. Aqueous solutions are less irritant than alcoholic ones. They should be applied for 12 hours or overnight – and not just to the pubic area, but to all surfaces of the body, including the perianal area, limbs, scalp, neck, ears and face (especially the eyebrows and the beard, if present). Treatment should be repeated after 1 week, and infected sexual partners should also be treated. Shaving the area is not necessary.

Infestations

Arthropods

Type of arthropod

Manifestations

Insects

Hymenoptera

Bee and wasp stings

Ant bites

Lepidoptera

Caterpillar dermatitis

Coleoptera

Blisters from cantharidin

Diptera

Mosquito and midge bites

Myiasis

Aphaniptera

Human and animal fleas

Hemiptera

Bed bugs

Anoplura

Lice infestations

Mites

Demodex folliculorum

Normal inhabitant of facial hair follicles

Sarcoptes scabei

Human and animal scabies

Food mites

Grain itch, grocer’s itch, etc.

Harvest mites

Harvest itch

Feather mites

In pet birds, nests, and sometimes feather pillows

House dust mite

Possible role in atopic eczema

Cheyletiella

Papular urticaria

Ticks

Tick bites. Vector of rickettsial infections and erythema migrans (p. 221)

Lice infestations (pediculosis)

Head lice

Cause

Presentation and course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Body lice

Cause

Presentation and course

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Pubic lice

Cause

Presentation

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree