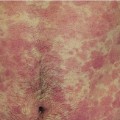

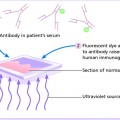

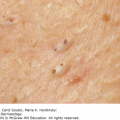

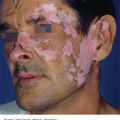

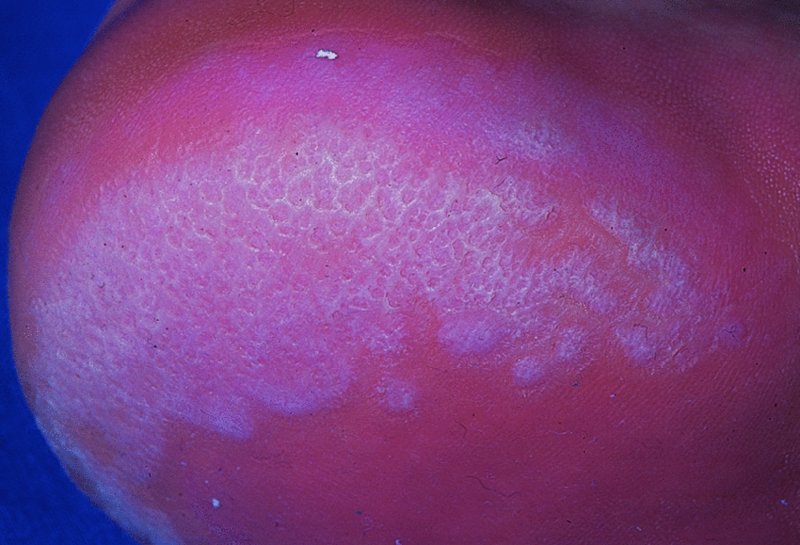

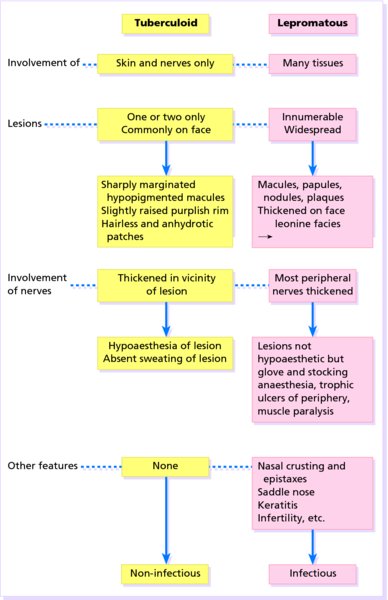

16 The surface of the skin teems with micro-organisms, which are most numerous in moist hairy areas, and areas rich in sebaceous glands. The move away from culture-based approaches to genomic characterization has revealed that the skin microbiome is greatly more diverse than we had previously thought and generally exists in a delicate balance with their human host. Organisms are found, in clusters, in irregularities in the stratum corneum and within the hair follicles. The resident flora is a mixture of harmless and poorly classified staphylococci, micrococci and diphtheroids. Staphylococcus epidermidis and aerobic diphtheroids predominate on the surface, and anaerobic diphtheroids (Propionibacteria sp.) deep in the hair follicles. As a general rule, Gram-positive species such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes colonize the skin above the waist, while Gram-negative bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococci are additionally found below the waist. Several species of lipophilic yeasts also exist on the skin. The proportion of the different organisms varies from person to person but, once established, an individual’s skin flora tends to remain stable and helps to defend the skin against outside pathogens by bacterial interference or antibiotic production. Nevertheless, overgrowth of skin diphtheroids can itself lead to clinical problems. The role of Propionibacteria in the pathogenesis of acne is discussed on p. 157. Overgrowth of aerobic diphtheroids causes the following conditions. The axillary hairs become beaded with concretions, usually yellow, made up of colonies of commensal diphtheroids. Clothing becomes stained in the armpits. Topical antibiotic ointments, or shaving, will clear the condition, and frequent washing with antibacterial soaps will keep it clear. The combination of unusually sweaty feet and occlusive shoes encourages the growth of diphtheroid organisms that can digest keratin. The result is a cribriform pattern of fine punched-out depressions on the plantar surface (Figure 16.1), coupled with an unpleasant smell (of methane-thiol). Fusidic acid or mupirocin ointment is usually effective, and antiperspirants (Formulary 1, p. 400) can also help. Occlusive footwear should be replaced by sandals and cotton socks if possible. Figure 16.1 Pitted keratolysis of the heel. Some diphtheroid members of the skin flora produce porphyrins when grown in a suitable medium. Overgrowth of these strains is sometimes the cause of symptom-free macular wrinkled, slightly scaly, pink, brown or macerated white areas, most often found in the armpits or groins, or between the toes. In diabetics, larger areas of the trunk may be involved. Diagnosis is helped by the fact that the porphyrins produced by these diptheroids fluoresce coral pink with Wood’s light. Topical fusidic acid or azoles will clear the condition. Staphylococcus aureus is not part of the resident flora of the skin other than in a minority who carry it in their nostrils, perineum or armpits. Carriage rates vary with age. Nasal carriage is almost invariable in babies born in hospital, becomes less frequent during infancy, and rises again during the school years to the adult level of roughly 30%. Rather fewer carry the organism in the armpits or groin. Staphylococci can also multiply on areas of diseased skin such as eczema, often without causing obvious sepsis. A minor breach in the skin’s defences is probably necessary for a frank staphylococcal infection to establish itself; some strains are particularly likely to cause skin sepsis. Of concern is the rise in incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the community and in hospitalized patients. This can result in abscesses and furunculosis as well as other infections. Prevention of emerging resistant strains is with a combination of scrupulous hygiene, patient isolation, antiseptic agents and restriction of antibiotics. Impetigo may be caused by staphylococci, streptococci, or by both together. It is the most common skin infection of children and occurs particularly in tropical or subtropical regions, or during summer months in the nothern hemisphere. As a useful rule of thumb, the bullous type is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, whereas the crusted ulcerated type is caused by β-haemolytic strains of streptococci. Both are highly contagious. Exfoliative toxins produced by S. aureus cleave the cell adhesion molecule desmoglein 1 (p. 8). If the toxin is localized this produces the blisters of bullous impetigo, but if generalized leads to more widespread blistering as in the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. A thin-walled flaccid clear blister forms on non-follicular skin, and may become pustular before rupturing to leave an extending area of exudation and yellowish varnish-like crusting (Figure 16.2). Lesions are often multiple, particularly around the face. The lesions may be more obviously bullous in infants. Superficial infection of the hair follicles (superficial folliculitis) with pus in the epidermis is also common. Figure 16.2 Impetigo on an uncommon site showing erosions, crusting and rupture blisters. The condition can spread rapidly through a family or class. It tends to clear even without treatment. Streptococcal impetigo can trigger an acute glomerulonephritis. Herpes simplex may become impetiginized, as may eczema. Always think of a possible underlying cause such as this. Recurrent impetigo of the head and neck, for example, should prompt a search for scalp lice. The diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds. Gram stains can be done or swabs can be taken and sent to the laboratory for culture, but treatment must not be held up until the results are available. Systemic antibiotics (such as flucloxacillin, erythromycin or cefalexin) are needed for severe cases or if a nephritogenic strain of streptococcus is suspected (penicillin V). For minor cases the removal of crusts by compressing them and application of a topical antibiotic such as neomycin, fusidic acid (not available in the United States), mupirocin or bacitracin will suffice (Formulary 1, p. 404). This term describes ulcers forming under a crusted surface infection. The site may have been that of an insect bite or of neglected minor trauma. The bacterial pathogens and their treatment are similar to those of impetigo. Whereas in impetigo the erosion is at the stratum corneum, in ecthyma the ulcer is full thickness, and thus heals with scarring. A furuncle is an acute pustular infection of a hair follicle, usually with Staphylococcus aureus. Infection spreads to the deep dermis, where small abscesses may form. Adolescent boys are especially susceptible to them. A tender red nodule enlarges, and later may discharge pus and its central ‘core’ before healing to leave a scar. Fever and enlarged draining nodes are rare. Most patients have one or two boils only, and then clear. The sudden appearance of many furuncles suggests a virulent staphlococcus including strains of community-aquired MRSA, or staphylococci expressing Panton–Valentine leucocidin toxin. A few unfortunate persons suffer from a tiresome sequence of boils (chronic furunculosis; Figure 16.3), often due to susceptibilty of follicles or colonization of nares or groins with pathogenic bacteria. Immunodeficiency is rarely the problem. Figure 16.3 Chronic furunculosis. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is an unusual complication of boils on the central face. Septicaemia may occur but is rare. The diagnosis is straightforward but hidradenitis suppurativa (p. 169) should be considered if only the groin and axillae are involved. A group of adjacent hair follicles becomes deeply infected with Staphylococcus aureus, leading to a swollen painful suppurating area discharging pus from several points. The pain and systemic upset are greater than those of a boil. Diabetes must be excluded. Treatment needs both topical and systemic antibiotics. Incision and drainage has been shown to speed up healing, although it is not always easy when there are multiple deep pus-filled pockets. Consider the possibility of a fungal kerion (p. 241) in unresponsive carbuncles. In this condition the skin changes resemble a scald. Erythema and tenderness are followed by the loosening of large areas of overlying epidermis (Figure 16.4). In children the condition is usually caused by a toxin produced by staphylococcal infection elsewhere (e.g. impetigo or conjunctivitis). Organisms in what may be only a minor local infection release exfoliative toxins that cleave the superficial skin adhesion molecule desmoglein 1 (p. 8) to disrupt adhesion high in the epidermis, causing the stratum corneum to slough off. With systemic antibiotics the outlook is good. The disorder affects children and patients with renal failure; most adults have antibodies to the toxin, and therefore are protected. In adults with widespread exfoliation, consider toxic epidermal necrolysis, which is usually drug-induced. The damage to the epidermis in toxic epidermal necrolysis is full thickness, and a skin biopsy will distinguish it from the scalded skin syndrome (p. 121). Figure 16.4 Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Bacterial toxins are also responsible for this condition, in which fever, a rash – usually a widespread erythema – and sometimes circulatory collapse are followed a week or two later by characteristic desquamation, most marked on the fingers and hands. Many cases have followed staphylococcal overgrowth in the vagina of women using tampons, although group A streptococci can also be responsible. The bacterial toxins act as superantigens, directly stimulating T cells and causing massive cytokine release. Systemic antibiotics and irrigation of the infected site are needed. Intravenous immunoglobulin may neutralize superantigen and reduce tissue damage. Erysipelas is an acute infection of the dermis or hypodermis. The first warning of an attack is often malaise, shivering and a fever. After a few hours the affected area of skin becomes red, and the eruption spreads with a well-defined advancing edge. Blisters may develop on the red plaques (Figure 16.5). Untreated, the condition can even be fatal, but it responds rapidly to systemic penicillin, sometimes given intravenously. The causative streptococci usually gain their entry through a split in the skin (e.g. between the toes or under an ear lobe). Figure 16.5 Erysipelas – note sharp spreading edge, here demarcated with a ballpoint pen. Treatment of erysipelas should include antibiotics active against streptococci, usually penicillin. The choice of oral or parenteral route is dictated by the severity of the infection. Recurrence occurs in up to 20% of erysipelas patients. This inflammation of the skin occurs at a deeper level than erysipelas. The subcutaneous tissues are involved; and the area is more raised and swollen, and the erythema less marginated than in erysipelas. Cellulitis often follows an injury and favours areas of hypostatic oedema. Streptococci, staphylococci, or other organisms may be the cause. Treatment is elevation, rest – sometimes in hospital – and systemic antibiotics, sometimes given intravenously and active against both staphylococci and streptococci. A combination of a macrolide with a streptogramin may be more effective than penicillins. Toe web intertrigo and lymphoedema are risk factors for the development of both erysipelas and cellulitis, which in turn predispose patients to persistent lymphoedema. It is important to treat these underlying factors as well as the bacterial infection to reduce the risks of recurrence. A mixture of pathogens, usually including streptococci and anaerobes, is responsible for this rare condition, which is a surgical emergency. Diabetics and post-surgical patients are predisposed. At first the infection resembles a dusky, often painful, cellulitis, but it quickly turns into an extending necrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Classically, the central area of skin involvement becomes anaesthetic due to cutaneous nerve damage. Hyponatraemia is often present and in a septic patient with clinical signs of soft tissue infection should arouse the doctor’s suspicions. A deep ‘stab’ incision biopsy through the skin into the fascia may be necessary to establish the diagnosis and to obtain material for bacteriological culture. Computed tomography, or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may help to establish how far the infection has spread. The prognosis is often poor despite early wide surgical debridement and prompt intravenous antibiotic administration, even when given before the bacteriological results are available. It is convenient to mention this here, but the causative organism is Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. and not a streptococcus. This Gram-positive rod infects a wide range of animals, birds and fish. In humans, infections are most common in butchers, fishmongers and cooks, the organisms penetrating the skin after a prick from an infected bone. The disease has become less common with improvements in the animal handling industry. Infections are usually mild, and localized to the area around the inoculation site. The swollen purple area spreads slowly with a clear-cut advancing edge. With penicillin the condition clears quickly; without it, resolution takes several weeks. The infective agent is the bacillus Bartonella (Rochalimea) henselae. A few days after a cat bite or scratch, a reddish granulomatous papule appears at the site of inoculation. Tender regional lymphadenopathy follows some weeks later, and lasts for several weeks, often being accompanied by a mild fever. The glands may discharge before settling spontaneously. There is no specific treatment. In immunosuppressed patients, most commonly those with HIV, Bartonella henselae causes bacillary angiomatosis (p. 237). Neisseria meningitides is a Gram-negative coccus that commonly colonizes the upper respiratory tract. Usually, it is only responsible for local infections such as conjunctivitis, but for unknown reasons it may rarely become invasive and cause a severe and life-threatening disease. Meningitis and septicaemia are not always easy to recognize in their early stages when their symptoms can be very similar to common illnesses such as influenza. The signs and symptoms do not appear in any order and some may not appear at all. Acute meningococcal septicaemia can present as a fulminating disease with septic shock and meningitis or more non-specifically with rigors, leg pain, headache, stiff neck, vomiting and pallor. A haemorrhagic rash with petechiae and then purpura (with no blanching or change on diascopy), found mainly on the trunk and limbs, is characteristic. An unwell feverish child with these skin signs should considered highly likely to have meningococcal disease. Diagnosis is confirmed by the isolation of N. meningitidis from blood or cerebrospinal fluid, but treatment with high dose intravenous benzyl-penicillin should be started as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Rifampicin prophylaxis can be used for close contacts. Trust your instincts, if you suspect meningitis or septicaemia and seek hospital help immediately. Infection with the causative organism, Treponema pallidum, may be congenital, acquired through transfusion with contaminated blood or by accidental inoculation. The most important route, however, is through sexual contact with an infected partner, and the incidence is currently rising, with concurrent HIV infection. If there is a high standard of antenatal care and testing, syphilis in the mother will be detected and treated during pregnancy, and congenital syphilis will be rare. Otherwise, stillbirth is a common outcome, although some children with congenital syphilis may develop the stigmata of the disease only in late childhood. The features of the different stages are given in Figure 16.6. After an incubation period (9–90 days), a primary chancre develops at the site of inoculation. Often this is genital, but oral and anal chancres are not uncommon. A typical chancre is a painless button-like ulcer of up to 1 cm in diameter accompanied by local lymphadenopathy. Untreated it lasts about 6 weeks and then clears leaving an inconspicuous scar. Figure 16.6 The stages of syphilis. The secondary stage may be reached while the chancre is still subsiding. Systemic symptoms and a generalized lymphadenopathy usher in eruptions that at first are macules and inconspicuous, and later papules and more obvious. Lesions are distributed symmetrically and are of a coppery ham colour. Sometimes they resemble pityriasis rosea or guttate psoriasis. Classically, there are obvious lesions on the palms and soles. Annular lesions are not uncommon. Condyloma lata are moist papules in the genital and anal areas. Other signs include a ‘moth-eaten’ alopecia and mucous patches in the mouth. The skin lesions of late syphilis may be nodules that spread peripherally and clear centrally, leaving a serpiginous outline. Gummas are granulomatous areas; in the skin they quickly break down to leave punched-out ulcers that heal poorly, leaving papery white scars. Even if left untreated, most of those who contract syphilis have no further problems after the secondary stage has passed. Others develop the cutaneous or systemic manifestations of late syphilis such as gummas and dementia. The skin changes of syphilis can mimic many other skin diseases. Always consider the following. The diagnosis of syphilis in its infectious (primary and secondary) stages has traditionally been confirmed using dark field microscopy to show up spirochaetes in smears from chancres, oral lesions or moist areas in a secondary eruption. Serological tests for syphilis become positive only some 5–6 weeks after infection (usually a week or two after the appearance of the chancre). The non-treponemal (rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL)) tests are 78–86% sensitive in primary and 100% sensitive in secondary syphilis, but may produce false positive results. Positive results are thus confirmed with more specific treponemal tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody/absorption (FTA/ABS) and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) tests, although HIV infection may cause false negative results. Serological tests may not become negative after treatment if an infection has been present for more than a few months and thus cannot be relied on to differentiate between and active and successfully treated infections. Patients with syphilis should be screened for concurrent sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhoea and HIV. This should follow the current national recommendations (see www.guidelines.gov) Penicillin is still the treatment of choice. Procaine penicillin is given parenterally for 10 days in early syphilis and 17 days in late stage disease or in early syphilis with neurological involvement. Benzithine penicillin can be given as a single intramuscular dose in primary or secondary syphilis. Doxycycline for 14 days or azithromycin for 10 days are alternatives for those with penicillin allergy. Patients with concomitant HIV infection need longer treatment and higher doses. Lumbar puncture is indicated in later stages as a guide to treatment. The use of long-acting penicillin injections overcomes the ever-present danger of poor compliance with oral treatment. Every effort must be made to trace and treat infected contacts. Yaws is distributed widely across the poorer parts of the tropics. The spirochaete, Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue, gains its entry through skin abrasions. After an incubation period of up to 6 months, the primary lesion, a crusting and ulcerated papule known as the ‘mother yaw’, develops at the site of inoculation; later it may enlarge to an exuberant raspberry-like swelling which lasts for several months before healing to leave an atrophic pale scar. In the secondary stage, other lesions may develop in any area but do so especially around the orifices. They are not unlike the primary lesion but are smaller and more numerous (‘daughter yaws’). Hyperkeratotic plaques may appear on the palms and soles. The tertiary stage is characterized by ulcerated gummatous skin lesions, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, and a painful periostitis that distorts the long bones. Serological tests for syphilis are positive. Treatment is with penicillin. The spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi is responsible for this condition, named after the town in the United States where it was first recognized. It is transmitted to humans by ticks of the genus Ixodes, commonly harboured by deer. Ticks need to remain attached to the skin for 1 or 2 days to be able to effectively pass the infection on. The site of the tick bite becomes the centre of a slowly expanding erythematous ring (erythema migrans; Figure 16.7). Later, many annular non-scaly plaques may develop. In the United States, a few of those affected develop arthritis and heart disease, both of which are less common in European cases. Other internal complications include meningitis and cranial nerve palsies. Treated early, the condition clears well with a 21-day course of oral amoxicillin or doxycycline: patients affected systemically need longer courses of parenteral antibiotics. Infection may be confirmed by serology, although this is usually negative in the first few weeks after inoculation and individuals living in endemic areas can have positive serologic tests, probably as a result of minor infection that resolved spontaneously. Serial testing can sometimes help to sort this out in patients with atypical rash. Figure 16.7 A tick bite was followed by erythema migrans. This condition is usually acquired through contact with infected livestock or animal products such as wool or bristles. Previously rare in industrialized countries, its importance increased after the infectious agent was used in the United States for a bioterrorism attack. Anthrax has two main clinical variants: the often fatal inhalational anthrax, which is outside the scope of this book; and cutaneous anthrax. The incubation period of the latter is usually 2–5 days. A skin lesion then appears on an exposed part, often in association with a variable degree of cutaneous oedema, which can sometimes be massive, especially on the face. Within a day or two, the original small painless papule shows vesicles that quickly coalesce into a larger single blister. This ruptures to form an ulcer with a central dark eschar, which falls off after 1–2 weeks leaving a scar. The skin lesions are often accompanied by fever, headache, myalgia and regional lymphadenopathy. The mortality rate for untreated cutaneous anthrax is up to 20%; with appropriate antibiotic treatment, this falls to less than 1%. Cultures of material taken from the vesicle may be positive in 12–48 hours; a Gram stain will show Gram-positive bacilli, occurring singly or in short chains. Quicker results may be obtained by a direct fluorescence antibody test, or by an enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay (ELISA) – both of which are currently available only at reference laboratories. Before the results are available, it is wise to assume that the organism is penicillin- and tetracycline-resistant, and to start treatment with ciprofloxacin at 400 mg intravenously every 12 hours or, for milder cases, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally every 12 hours. The latter dose is suitable for prophylactic use in those who are known to have been exposed to spores. A switch to an alternative regimen can be made once the antibiotic sensitivity of the organism has been established. At present, anthrax vaccine is in short supply; it requires six injections over 18 months, with subsequent boosters, to prevent anthrax. The spores of Bacillus anthracis, the causative organism, are highly resistant to physical and chemical agents. Skin lesions are important clues to the diagnosis of this condition, in which the symptoms and signs of classic gonorrhoea are usually absent. The patient, usually a menstruating woman with recurring fever and joint pains, develops sparse crops of skin lesions, usually around the hands and feet. The grey, often haemorrhagic, vesicopustules are characteristic. Rather similar lesions are seen in chronic meningococcal septicaemia. Most infections in the United Kingdom are caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mycobacterium bovis infection, endemic in cattle, can be spread to humans by milk, but human infection with this organism is now rare in countries where cattle have been vaccinated against tuberculosis and the milk is pasteurized. The steady decline of tuberculosis in developed countries has been reversed in some areas where AIDS is especially prevalent. Dormant tuberculosis of the skin can also be reactivated by systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppresants and anti-tumour necrosis factor biological agents. Inocculation into skin causes a wart-like lesion at the site. Systemic spread to the skin (lupus vulgaris; Figure 16.8) can follow from an underlying infected lymph node or from a pulmonary lesion. Lesions occur most often around the head and neck. A reddish-brown scaly plaque slowly enlarges, and can damage deeper tissues such as cartilage, leading to ugly mutilation. Scarring and contractures may follow. Figure 16.8 A plaque with the brownish tinge characteristic of lupus vulgaris. Diascopy was positive. Diascopy (p. 36) shows up the characteristic brownish ‘apple jelly’ nodules. The clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by a biopsy. The skin overlying a tuberculous lymph node or joint may become involved in the process. The subsequent mixture of lesions (irregular puckered scars, fistulae and abscesses) is most commonly seen in the neck. A number of granulomatous skin eruptions have, in the past, been attributed to a reaction to internal foci of tuberculosis. Of these, the best authenticated – by finding mycobacterial DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) – are the papulonecrotic tuberculides – recurring crops of firm dusky papules, which may ulcerate, favouring the points of the knees and elbows. Most tuberculosis-like granulomas of the face are forms of granulomatous rosacea. In erythema induratum, deep purplish ulcerating nodules occur on the backs of the lower legs, usually in women with a poor ‘chilblain’ type of circulation. Sometimes, this is associated with a tuberculous focus elsewhere. Erythema nodosum (p. 107) may also be the result of tuberculosis elsewhere. Biopsy for: The treatment of all types of cutaneous tuberculosis should be with a full course of a standard multidrug antituberculosis regimen. There is no longer any excuse for the use of one drug alone. Outbreaks of pulmonary tuberculosis are reminders that this disease has not yet been conquered and that vigilance is important. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination of schoolchildren, immunization of cattle and pasteurization of milk remain the most effective protective measures. Mycobacterium leprae was discovered by Hansen in 1873, but has still not been cultured in vitro, although it can be made to grow in some animals (e.g. armadillos, mouse foot-pads). In humans, the main route of infection is through nasal droplets from cases of lepromatous leprosy. Leprosy is present in around 120 countries worldwide, particularly in the tropics and subtropics with hotspots in central Africa, parts of Asia and Brazil. The World Health Organization’s aim to eliminate (i.e. have less than 1 registered case per 10 000 population) the disease worldwide by 2000 has not been met, but the incidence is slowly falling, and less than a quarter of a million new diagnoses are made each year. The incubation period is usually 3–5 years, although it can be up to 20 years. The range of clinical manifestations and complications depends upon the immune response of the patient (Figure 16.9). Those with a strong cell-mediated immune response develop a paucibacillary tuberculoid type (Figure 16.10) and those with a poor response a multibacillary lepromatous type. Lymphocytic infiltration leads to earlier nerve thickening and damage in the tuberculoid than lepromatous disease (Figure 16.11). A few hypopigmented, discrete macules are found. Widespread haematogenous spread occurs in lepromatous leprosy. Some patients develop macular lepromatous leprosy with widespread hypopigmented macules. In the nodular form of lepromatous leprosy, patients develop nodules, loss of eyebrows and the corrugated facial appearance known as leonine facies. Between the extremes lies a spectrum of reactions classified as ‘borderline’. Those most like the tuberculoid type are known as borderline tuberculoid (BT) and those nearest to the lepromatous type as borderline lepromatous (BL). The clinical differences between the two polar types are given in Figure 16.12. Figure 16.9 The spectrum of leprosy: tuberculoid to lepromatous. Figure 16.10 Tuberculoid leprosy: subtle depigmentation with a palpable erythematous rim at the upper edge. Figure 16.11 The ‘leonine’ facies of lepromatous leprosy. Figure 16.12 Tuberculoid and lepromatous leprosy. Consider the following – in none of which is there any loss of sensation. Widespread leishmaniasis can closely simulate lepromatous leprosy. The nodules seen in neurofibromatosis and mycosis fungoides, and multiple sebaceous cysts, can cause confusion, as can the acral deformities seen in yaws and systemic sclerosis. Leprosy is a great imitator. In endemic countries, diagnosis is based on the clinical findings of typical skin lesions of leprosy in association with anaesthetic patches and possibly thickened nerves with demonstrable loss of function, combined with positive slit skin smears. Histology from a skin or nerve biopsy and PCR examination for M. leprae DNA in biopsy material can help the diagnosis, but these investigations are not often available in resource-poor countries, where leprosy mostly occurs. Slit skin smears are taken from six sites at cool parts of the body (e.g. ear lobes, buttocks, forehead). Cuts are made 5 mm long by 3 mm deep, and scraped with the scalpel blade sideways. The scrapings are stained with a modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain, and the number of bacteria counted to determine whether the patient has multibacillary or paucibacillary leprosy. Lepromin testing is of no use in the diagnosis of leprosy but, once the diagnosis has been made, it will help in deciding which type of disease is present (positive in tuberculoid type). The development of resistance to single agent treatment with dapsone means that multidrug therapy (MDT) is now offered free to all patients with leprosy by the World Health Organization. Patients with multibacillary leprosy are treated with 12 months of rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine. Those with paucibacillary disease receive 6 months of rifampicin and dapsone. A brief period of isolation is needed only for patients with infectious lepromatous leprosy; with treatment they quickly become non-infectious and can return to the community. However, their management should remain in the hands of physicians with a special interest in the disease. Treating lepra reactions and reducing nerve damage is an important part of leprosy treatment as is teaching patients to cope with the results of nerve damage and anaesthesia.

Infections

Bacterial infections

The resident flora of the skin

Trichomycosis axillaris

Pitted keratolysis

Erythrasma

Staphylococcal infections

Impetigo

Cause

Presentation

Course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigation and treatment

Ecthyma

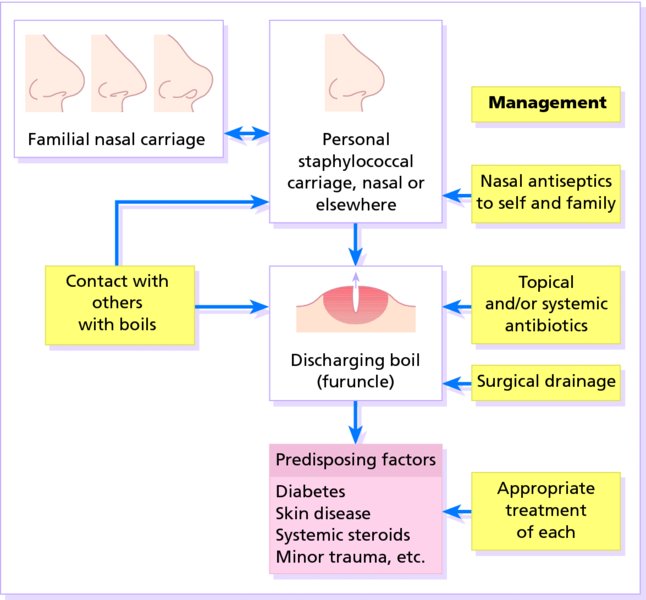

Furunculosis (boils)

Cause

Presentation and course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations in chronic furunculosis

Treatment

Carbuncle

Scalded skin syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome

Streptococcal infections

Erysipelas

Cellulitis

Necrotizing fasciitis

Erysipeloid

Cat-scratch disease

Meningococcal infection

Spirochaetal infections

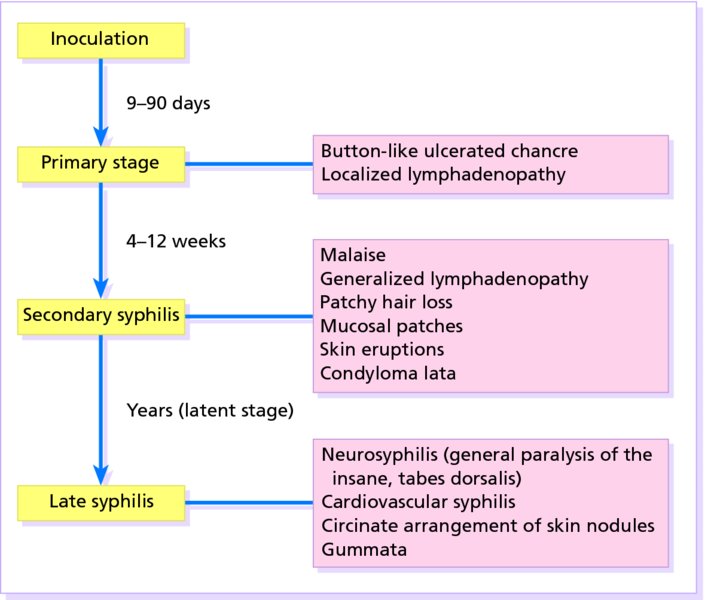

Syphilis

Cause

Presentation

Congenital syphilis.

Acquired syphilis.

Clinical course

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Yaws

Lyme disease

Other infections

Cutaneous anthrax

Gonococcal septicaemia

Mycobacterial infections

Tuberculosis

Inoculation tuberculosis

Scrofuloderma

Tuberculides

Erythema induratum (Bazin’s disease)

Investigations

Treatment

Prevention

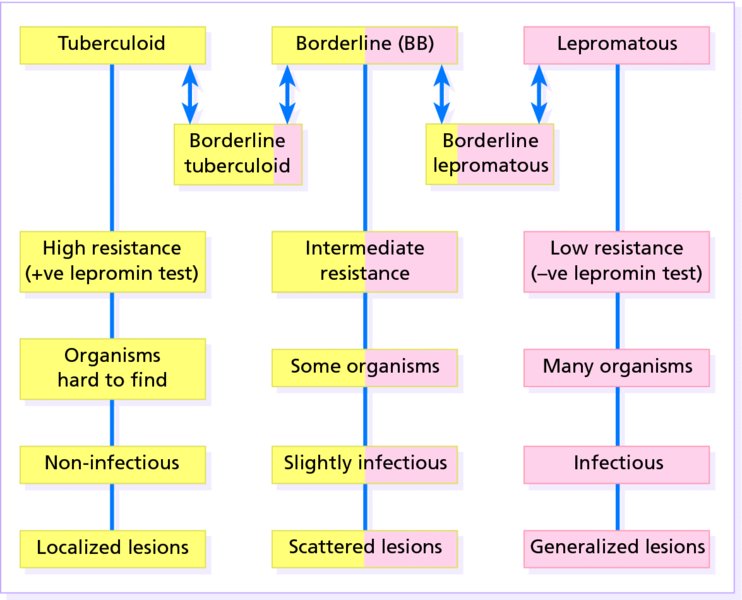

Leprosy

Cause

Epidemiology

Presentation

Differential diagnosis

Tuberculoid leprosy.

Lepromatous leprosy.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree