Chapter 8

Immunobullous and Other Blistering Disorders

OVERVIEW

- Blisters arise from destruction or separation of epidermal cells by trauma, viral infection, immune reactions, oedema as in eczema or inflammatory causes such as vasculitis.

- Immune reactions at the dermoepidermal junction and intraepidermally cause blisters.

- Susceptibility is inherited; trigger factors include drugs, foods, viral infections, hormones and ultraviolet radiation.

- Differential diagnosis depends on specific features, in particular the duration, durability and distribution of lesions.

- The most important immunobullous conditions are bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) and linear IgA.

- Investigations should identify underlying causes and the site and nature of any immune reaction in the skin.

- Management includes topical treatment, immunosuppressive drugs and a gluten-free diet.

Introduction

Blisters, whether large bullae or small vesicles, can arise in a variety of conditions. Blisters may result from destruction of epidermal cells (a burn or a herpes virus infection). Loss of adhesion between the cells may occur within the epidermis (pemphigus) or at the basement membrane (pemphigoid). In eczema there is oedema between the epidermal cells, resulting in spongiosis. Sometimes, there are associated inflammatory changes in the dermis (erythema multiforme/vasculitis) or a metabolic defect (as in porphyria).

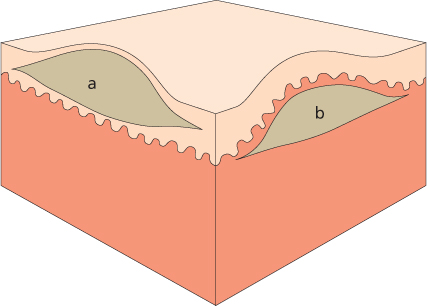

The integrity of normal skin depends on intricate connecting structures between cells (Figure 8.1). In autoimmune blistering conditions autoantibodies attack these adhesion structures. The level of the separation of epidermal cells within the epidermis is determined by the specific structure that is the target antigen. Clinically, these splits are visualised as superficial blisters which may be fragile and flaccid (intraepidermal split) or deep mainly intact blisters (subepidermal split). Therefore, the clinical features can be used to predict the level of the underlying target antigen in the skin.

Figure 8.1 Section through the skin with (a) intraepidermal blister and (b) subepidermal blister.

Pathophysiology

Susceptibility to develop autoimmune disorders may be inherited, but the triggers for the production of these skin-damaging autoantibodies remains unknown. In some patients possible triggers have been identified including drugs (rifampicin, captopril and d-penicillamine), certain foods (garlic, onions and leeks), viral infections, hormones, UV radiation and X-rays.

Bullous pemphigoid results from IgG autoantibodies that target the basement membrane cells (hemidesmosome proteins BP180 and BP230). Studies have demonstrated a reduction in circulating regulatory T cells (Treg) and reduced levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10) in patients with bullous pemphigoid, which partially correct following treatment. Complement activates an inflammatory cascade, leading to disruption of skin cell adhesion and blister formation. The subepidermal split leads to tense bullae formation.

Pemphigus vulgaris results from autoantibodies directed against desmosomal cadherin desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) found between epidermal cells in mucous membranes and skin. This causes the epidermal cells to separate, resulting in intraepidermal blister formation. This relatively superficial split leads to flaccid blisters and erosions (where the blister roof has sloughed off). Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is a rare autoimmune skin disease characterised by subcorneal blistering and IgG antibodies directed against desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) usually manifested at UV-irradiated skin sites.

DH is caused by IgA deposits in the papillary dermis which results from chronic exposure of the gut to dietary gluten triggering an auto-immunological response in genetically susceptible individuals. IgA antibodies develop against gluten-tissue transglutaminase (found in the gut) and these cross react with epidermal-transglutaminase leading to cutaneous blistering.

Differential diagnosis

Many cutaneous disorders present with blister formation. Presentations include large single bullae through to multiple small vesicles, and differentiating the underlying cause can be a clinical challenge (Table 8.1). The history of the blister formation can give important clues to the diagnosis, in particular the development, duration, durability and distribution of the lesions—the ‘four Ds’.

Table 8.1 Differential diagnosis of immunobullous disorders—other causes of cutaneous blistering.

| Other causes of cutaneous blistering | Key clinical features | Diagnostic tests | Further reading |

| Erythema multiforme | Target lesions with a central blister, acral sites | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis | Mucous membrane involvement, Nikolsky-positive, eroded areas of skin | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

| Chicken pox | Scattered blisters in crops appear over days | Viral swab to detect VZV; serology | Chapter 14 |

| Herpes simplex/varicella zoster virus | Localised blistering of mucous membranes or dermatomal | Vesicle fluid for viral analysis | Chapter 14 |

| Staphylococcus impetigo | Golden crusting associated with blisters | Bacterial swab for culture | Chapter 13 |

| Insect bite reactions | Linear or clusters of blisters, very itchy | Clinical diagnosis | Chapter 17 |

| Contact dermatitis | Exogenous pattern of blisters | Patch testing | Chapter 4 |

| Phytophotodermatitis | Blisters where plants/extracts touched the skin plus sunlight exposure | Clinical diagnosis | Chapter 6 |

| Porphyria | Fragile skin with scarring at sun-exposed sites | Urine, blood, faecal analysis for porphyrins | Chapter 6 |

| Fixed drug eruption | Blistering purplish lesion/s at a fixed site each time drug taken | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

Development

If erosions or blisters are present at birth then genodermatoses must be considered in addition to cutaneous infections. Preceding systemic symptoms may suggest an infectious cause such as chicken pox or hand, foot and mouth disease. A tingling sensation may herald herpes simplex, and pain, herpes zoster. If the lesions are pruritic, then consider DH or pompholyx eczema. Eczema may precede bullous pemphigoid.

Duration

Some types of blistering arise rapidly (allergic reactions, impetigo, erythema multiforme and pemphigus), while others have a more gradual onset and follow a chronic course (DH, pityriasis lichenoides, porphyria cutanea tarda and bullous pemphigoid). The rare genetic disorder epidermolysis bullosa is present from, or soon after, birth and has a chronic course.

Durability

The blisters themselves may remain intact or rupture easily and this sign can help elude the underlying diagnosis. Superficial blisters in the epidermis have a fragile roof that sloughs off easily leaving eroded areas typically seen in pemphigus vulgaris, porphyria, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, staphylococcal scalded skin and herpes viruses. Subepidermal blisters have a stronger roof and usually remain intact and are classically seen in bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA and erythema multiforme. Scratching can result in traumatic removal of blister roofs, which may confuse the clinical picture.

Distribution

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree