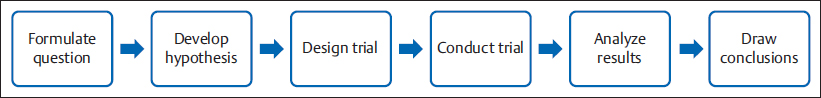

11 How to Set Up a Research Protocol in Plastic Surgery Abstract There has been a shift in the paradigm of medical practice, from a pragmatic approach to understanding and treating an illness to an evidence-based medicine approach. Evidence-based medicine uses the scientific method to answer clinical questions and generate knowledge. This process follows preestablished steps according to the scientific method, and starts with a question. The research question should be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. When one is designing a research protocol, it is important to establish what kind of question to ask: diagnostic, etiologic, prognostic, or therapeutic. There are many ways of answering each type of question; designing the best way to answer a given question generates more accurate, higher-level evidence. This chapter provides an overview of how to set up a research protocol in plastic surgery. Keywords: diagnosis, etiology, prognosis, research protocol, research question, statistics, therapy We are surrounded by clinical questions in our daily practice. Is my patient sick? What is causing his/her sickness? Will it cause disability? Which treatment should I give him/her? Since 1992, there has been a shift in medical paradigms, and the traditional ways of responding to these questions have changed toward evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based medicine uses the scientific method to answer clinical questions and places lower value on nonsystematic clinical experience. The scientific method is the process by which scientists attempt to construct a reliable and consistent representation of the world. It consists of four steps: (1) identification and description of a phenomenon, (2) formulation of a hypothesis to explain the phenomenon, (3) use of the hypothesis to predict future observations, and (4) experiments to test the predictions. The search for the cause of diseases is one of the most important questions we face. Causation is an essential concept in the practice of epidemiology. For Rothman, “A cause is an act or event or a state of nature which initiates or permits, alone or in conjunction with other causes, a sequence of events resulting in an effect.” Because the only way to know what causes a determined effect is the contrafactual model of causation, we can only talk about association or relation between a possible cause and an effect. Statistical methods can be used to determine if two or more events are connected. In statistics, this is referred to as inference. There are many statistical tests for hypotheses that can determine the association, or lack thereof, between two or more events. The scientific method in general and as applied in medicine follows a sequence of steps that begin with a research question and end with analysis and conclusions ( Every protocol must start by asking a question. Questions arise from personal experience, problems encountered, knowledge, new ideas, new technologies, skepticism, imagination, observation, teaching, creativity, and so on. The work begins with formulating a good research question that is feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant (FINER). A good clinical question has three parts: (1) patients or a population, (2) intervention and comparison, and (3) outcomes. This method of formulating a research question is called the PICO strategy (patient or problem, intervention or indicator, comparison, and outcome). Note The PICO Strategy To determine if lipoabdominoplasty is associated with better outcomes than abdominoplasty without liposuction, the following elements would constitute a PICO strategy. Patient (or problem): Women with abdominal ptosis. Intervention (or indicator): Lipoabdominoplasty. Comparison: Abdominoplasty without liposuction. Outcome: Quality of life measured by the Body-QoL instrument. The research question could be written as follows: In healthy women with abdominal ptosis, does lipoabdominoplasty provide better quality of life compared with standard abdominoplasty? Once a FINER question has been formulated, the next step is to perform a thorough bibliographic background to determine whether the question has been asked before, and, if so, to study any previous attempts to answer it. After gathering the relevant information, you should have an idea of how previous researchers have approached the problem, and with that knowledge decide which area of clinical epidemiology (diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, or etiology) applies to your question. When facing a patient with an illness, as doctors we have the difficult task of elaborating a correct diagnosis. Fortunately, we have diverse tests to help us rule out or confirm a diagnosis. These diagnostic tests have several features that allow us to decide how accurate the diagnosis will be after applying the test, and whether the test is even worth performing. These features are extracted from conclusions of diagnostic studies. So if you have developed a new diagnostic test and you want to prove its use and accuracy, you should conduct a diagnostic study. On the other hand, if you already know the diagnosis of your patient, but you need to know the prognosis with or without treatment, you search for prognostic studies. These studies are designed to determine which course the disease will take. If you know your patient’s diagnosis and prognosis, you will need to determine the most effective treatment to administer to maximize your patient’s well-being. Treatment studies help answer these questions. It can be difficult to determine why a patient is diseased. Doing so requires a profound knowledge of the disease’s pathophysiology. Etiology studies aim to find the cause of pathology. A subgroup of studies that does not fit into any of the preceding categories includes clinical cases, case series, and presentations of surgical technique. These types of studies are the oldest and most popular types of medical literature worldwide. However, they are highly criticized because, with just one case or a small case series, authors may arrive at the wrong conclusions. In fact, these types of publications are rarely cited, so many journals reject them to avoid lowering their impact and credibility. Although the level of evidence of case reports and case series is at the lowest level of the evidence hierarchy ( Clinical case reports consist of a detailed description of the clinical record, treatment, complications, and follow-up of a single patient. You should highlight the special characteristics why you believe this particular case is worth reporting. Case series are similar to clinical case reports, but rather than reporting on a single patient they report on a group of patients with a similar characteristic. For a study to be considered a case series, it should include between 2 and 10 cases. Novel surgical techniques, such as face transplants and high-definition liposculpture, are commonly first reported in this type of report. These publications help to update the international surgical community about the latest surgical techniques. All of these reports should come with a full research of the existing literature Novel surgical techniques, such as face transplants and high-definition liposculpture, are commonly first reported as surgical techniques. Every research protocol includes at least the following sections ( Research question: Research questions arise from many backgrounds, such as personal experiences, knowledge, and imagination. As mentioned earlier, a good research question must be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. Your research question must be well formulated because the hypothesis, objectives, and methods will directly derive from it. Table 11.1 Common sections of a research protocol

11.1 Introduction

Fig. 11.1).

Fig. 11.1).

11.2 Clinical Question and Types of Study

11.2.1 Diagnosis

11.2.2 Prognosis

11.2.3 Treatment

11.2.4 Etiology

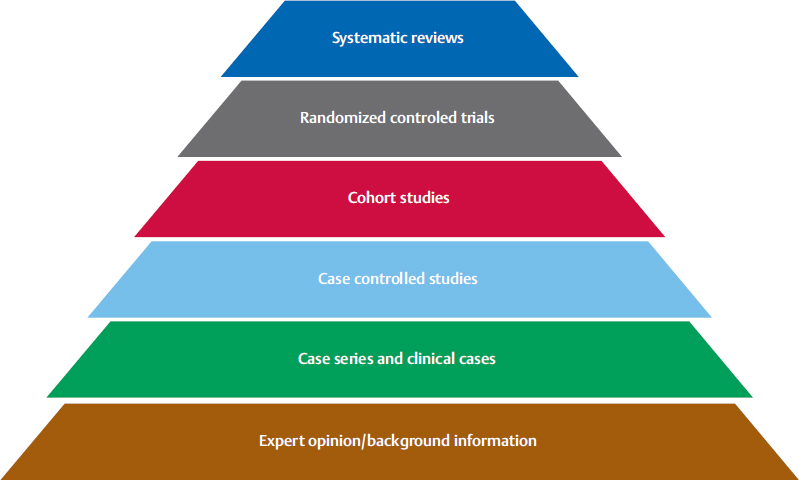

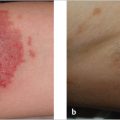

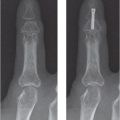

Fig. 11.2), their“open format” makes them useful for providing atypical presentations of diseases, difficult and uncommon diagnoses, rare conditions, and novel surgical techniques. Also, because randomized clinical trials may exclude many patients, for example patients with polypharmacy or with more than two comorbidities, case reports and case series may help us to observe unknown effects of therapies on these patients. For surgeons, and especially plastic surgeons, clinical knowledge is more easily recalled when it arises from reallife reports.

Fig. 11.2), their“open format” makes them useful for providing atypical presentations of diseases, difficult and uncommon diagnoses, rare conditions, and novel surgical techniques. Also, because randomized clinical trials may exclude many patients, for example patients with polypharmacy or with more than two comorbidities, case reports and case series may help us to observe unknown effects of therapies on these patients. For surgeons, and especially plastic surgeons, clinical knowledge is more easily recalled when it arises from reallife reports.

11.2.5 Clinical Cases

11.2.6 Case Series

11.2.7 Surgical Techniques

11.3 Basic Components of a Research Protocol

Table 11.1):

Table 11.1):

Research question |

Literature review |

Objectives of the research |

Population, patients, study center, inclusion and exclusion criteria |

Intervention |

Measurements |

Statistics |

Literature review: Searching the literature for previous attempts to answer your research question, together with a complete knowledge of the disease’s pathophysiology, is paramount to establishing the background of your research and to more properly designing your protocol.

Objectives: The objectives are declaratory statements that provide information about the type of study to be conducted, and they define the specific aims of the study. The primary objective should be coupled with the hypothesis of the study. Secondary objectives should state the aims to help.

Intervention: The intervention you want to study must be well characterized. It may be a treatment or a disease, depending on the type of study you are conducting; also, depending on your design, the intervention can be assigned by the researcher (experimental study), or chosen by the patient or the patient’s physician (observational study).

Measurements: The way you are going to measure your outcomes should be well defined and established. Your outcomes could be a clinical variable or an indirect variable. Clinical variables, such as death, complications, hospital admission, quality of life, are more significant, but you may not be able to measure them. In those cases you can use an indirect variable, such as biological markers. We strongly advise using patient-reported outcomes, such as the Body-QoL or the Breast-Q, for measuring outcomes in plastic surgery.

Statistics: Depending on the type of study you are conducting, statistical analysis can be used to describe your results or find association between interventions and outcomes.

11.4 Measuring the Accuracy of a Diagnostic Test

Establishing a correct diagnosis is an important part of our daily work. To reach the right diagnosis, we frequently need to perform some diagnostic tests. Nevertheless, to interpret the results of those tests you need to be familiarized with some basic principles about them.

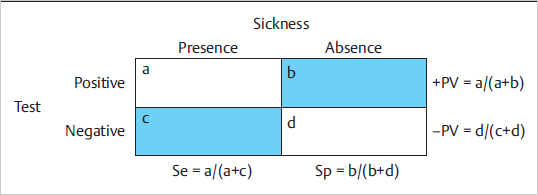

First of all, establishing a diagnosis is an imperfect process, which gives as a result a probability of having the alleged illness. If you have a diagnostic test and the presence of illness, and you represent it on a 2 × 2 table ( Fig. 11.3), then there will be patients correctly diagnosed (true-positive or true-negative), and patients erroneously diagnosed (false-positive or false-negative).

Fig. 11.3), then there will be patients correctly diagnosed (true-positive or true-negative), and patients erroneously diagnosed (false-positive or false-negative).

Because we do not know the truth, we use the best-known diagnostic method there is—the gold standard or the standard of comparison.

Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of individuals that are truly sick and have a positive result in the test, and specificity as the proportion of individuals that are truly healthy and have a negative result in the test.

Sensitivity and specificity are intrinsic properties of a test and are calculated with individuals we already know whether they are sick or not. But what we really need to know is, given the result of the test, if our patient is sick or not. The positive predictive value is defined as the probability of sickness of an individual with a positive result on the test. The negative predictive value is the probability of not being sick when the result of the test is negative. The main difference between sensitivity, specificity, and positive or negative predictive value is that sensitivity and specificity are intrinsic properties of the test, whereas predictive value depends on the population being tested.

If you want to do the math, you can look at the 2 × 2 table ( Fig. 11.3) and see that sensitivity is a/(a + c), specificity is d/(b + d), positive predictive value is a/(a + b), and negative predictive value is d/(c + d). Another way to calculate the positive predictive value is

Fig. 11.3) and see that sensitivity is a/(a + c), specificity is d/(b + d), positive predictive value is a/(a + b), and negative predictive value is d/(c + d). Another way to calculate the positive predictive value is