Fig. 1.1

Dr William Halsted (1852–1922) photographed by John H. Stocksdale (1922) [From: Images from the History of Medicine—National Library of Medicine, NIH; this item has no reserved right]

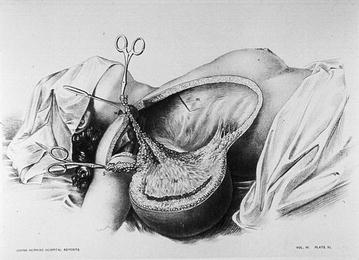

Fig. 1.2

Table reporting a radical mastectomy according to William Halsted technique performed at the John Hopkins Hospital [From: Images from the History of Medicine—National Library of Medicine, NIH; this item has no reserved right]

Meanwhile, BCS has become the standard operation for early breast cancer since Veronesi et al. [6] and Fisher et al. [7] reported the results of large studies in the 1980s. Results from these experiences represented an important break through with the past since they emphasized that the treatment of breast cancer could reconcile a conservative approach to the safety of radical treatment in oncology. From that time on, new impulse toward finding alternative more conservative surgical treatment was generated.

Both mastectomy and BCS have strongly and rapidly evolved in the last few years, leading to the modern surgical approach of the present millennium: classical lumpectomy/quadrantectomy have evolved into targeted oncoplastic treatments in BCS, while a further step beyond simple and even SSM with immediate reconstruction has been done, leading to the new concept of the so-called “conservative mastectomies”, which include now safe skin and nipple-areola complex preservation [8] (Fig. 1.3). Actually a broader spectrum of techniques are available now, so that the modern breast surgery has become a targeted treatment according with many variables: breast size and shape, tumor’s stage and biology, and patient’s desire and point of view.

The gap between BCS and mastectomy has been progressively reduced by modern approach, and minimally invasive mastectomy is coming to almost fill this gap.

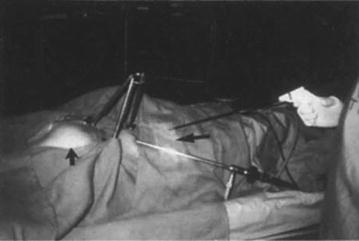

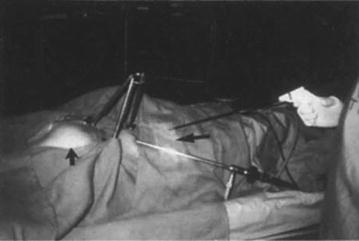

The first report regarding video-assisted surgery for breast cancer was written by Friedlander et al. [9] in 1995. They performed experimental surgery using an endoscope and an original tripod elevator initially on porcine models and thereafter on cadavers (Fig. 1.4). Their surgery consisted of total glandectomy, axillary dissection, and reconstruction of the breast with the rectus abdominous muscle. They thought of applying this surgery to patients with large ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ who required complete removal of the mammary gland. They also suggested the application of such surgery for benign breast disease.

Fig. 1.4

The first experimental experience dealing with endoscopic breast surgery performed by Friedlander using a tripod used for creating an operative working space in swine [84]

This experience is rooted in esthetic breast surgery where the possibility of operating in the mammary lodge with small skin incisions was obviously very attractive for both patients and plastic surgeons. Since Kompatscher [10] described the technique of endoscopic capsulotomy of capsular contracture after breast augmentation in 1992, numerous reports regarding video-assisted breast augmentation have been produced [11–18]. Today, it has become a standard technique for breast augmentation. On the other hand, video-assisted surgery for breast tumors has been examined only very recently. As a new surgical technique, it may still be challenging, but it has already showed the potential of becoming an important alternative approach for both benign and malignant tumors of the breast.

1.3 Endoscopic Breast Surgery in Eastern Countries: The Solution to a Specific Medical and Cultural Need

In the western countries’ literature, no clinical application has been reported since the first experimental Friedlander’ study. However, the idea found its first clinical applications in eastern countries (Korea, China, and Japan) where the need to operate, producing little visible scarring was not only a medical but also a cultural need.

First, the endoscopic surgery of the breast provided a brand new alternative for the prevention of keloids in a very sensitive site as the anterior chest wall.

Hypertrophic scars and keloids exclusively develop in humans [19, 20] with the same prevalence in male and female sexes and the highest incidence in the second decade [20–22]. The incidence of hypertrophic scarring is about 39–68 % after surgery and 33–91 % after burns, depending on the depth of the wound [23–26].

There seems to be no valid data available about their regional susceptibility, although it was thought that hypertrophic scars are related to forces opposite to tension, [27] because hypertrophic scar contractures occur only on the flexor surfaces of the joints and never on the extensor surfaces, [28] whereas wounds that are oriented in the relaxed skin tension lines generally heal with normal scar formation [29]. Keloids are seen in individuals of all races, except albinos, but occur approximately 15 times more often in patients with darker compared with lighter skin [30–32]. Negroid, Spanish, and Asian people have proved to be more susceptible and develop keloids in 4.5–16 % [30–32] of the cases. Unexplained is their regional susceptibility: the anterior chest, shoulders, earlobes, upper arms, and cheeks have a higher predilection for keloid formation, whereas eyelids, genitalia, palms, soles, cornea, and mucous membranes and even the umbilical cord, are less affected [33–37].

Based on this evidence, and considering: the high tension usually developed by the scar after a mastectomy, the site of the scar on the anterior chest wall and the increased susceptibility to keloid in the Asian population, then we understand what could be the high expectations of the use of endoscopic breast surgery for the reduction of disfiguring scars in Asia.

The development of endoscopic surgery in the East has also been facilitated by the presence of a cultural factor rooted for centuries in the culture of the peoples of those latitudes. Having a perfectly uniform white complexion is considered a hallmark of beauty and social success.

The desire for pale skin has roots that run deep in India’s history. It is entwined with Hinduism’s complex social hierarchy, or caste system. In India, white skin is considered as a mark of class and caste as well as an asset. A white complexion was seen as noble and aristocratic. Those higher up the scale generally tend to have paler skins because the rich and educated could afford to stay indoors, while the poor and uneducated were forced to work outdoors.

In Asia, women were deeply influenced by the concept that a white complexion is powerful enough to hide a number of faults. In ancient China and Japan, the saying “one white covers up three ugliness” was passed through the generations. Asian countries have long histories of utilizing white skin as a key criterion of personal beauty. In China, “milk-white” skin is a symbol of beauty. In Korea, flawless skin like white jade and an absence of freckles and scars have been preferred since the first dynasty in Korean history.

Ancient cultures used botanicals and mineral compositions of various kinds to facilitate skin lightening. Several of these materials, researched in recent years, have been found to contain natural enzyme/hormone inhibitors, antioxidants, and sunscreens. Chinese were known to ground pearl from seashells into powder and swallow it to whiten their skin, while across the Yellow Sea, applying white powder to the face has been considered a woman’s moral duty since the Edo period. In Korea, various methods of lightening the skin have long been used such as applying miansoo lotion and dregs of honey. Historically, women in South India bathed with turmeric which is now known for its skin lightening and anti-inflammatory properties.

1.4 Endoscopic Breast Surgery: Development of a New Technical Approach

Clinical reports of video-assisted surgery for breast tumors are briefly reported in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Clinical reports of video-assisted surgery for breast tumors

Years | Author | N. pts | Indications | Endoscopic intervention | Access to the gland | Technique for working space creation | Dissection technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1997 | Yamagata et al. | BC | BCS | Areola | External retraction method | ||

1998 | Tamaki et al. | 7 | BC < 2, 5 cm | BCS + AD | Axilla | External retraction method | Bipolar scissors |

1998 | Kitamura et al. | 6 | Benign | Tumorectomy | Inframammary or axilla + other sites (3 incisions) | Dissection balloon, CO2 insufflation 5–6 mmHg | Harmonic scalpel |

1999 | Ishiguro et al. | Axilla | External retraction method | ||||

2001 | Tamaki et al. | 6 | BC < 2 cm | BCS | Circumareolar incision | External retraction method | |

2001 | Kitamura et al. | 36 | Benign | Inframammary or axilla + other sites (3 incisions) | Dissection balloon, CO2 insufflation 5-6 mmHg | Harmonic scalpel | |

2001 | Osani et al. | Axilla | CO2 insuflation, low pressure | Blunt dissection | |||

2001 | Sawai et al. | Axilla | External retraction method and CO2 insuflation, low pressure | ||||

2002 | Kitamura et al. | 21 | BC 19 m FU | SM + P-rec | 6 cm Axilla, | External retraction method vs CO2 insufflation 5–6 mmHg | ? (harmonic scalpel?) |

2002 | Nakajima et al. | 17 | BC 18 m FU | SM + AD + LDR | 5–7 cm Axilla | (lifting fan) External retraction method | Bipolar scissors |

2002 | Ho et al | 9 | Early BC | SM + AD + P-rec | 5 cm Axilla ± inferior circumareolar | External retraction method | Harmonic scalpel |

2004 | Owaki et al. | 6 | BC < 1, 5 cm | BCS | 5 cm Axilla ± periareolar (inner Q) | Double retractor method | No data |

2006 | Lee et al. | 20 | BC < 3 cm | BCS | 2, 5 cm axilla and periareolar | Double retractor method | Tunnel technique, powerstar scissors |

2006 | Yamashita and Shimizu | 100 | 82 early BC 18 Benign T | 80 BCS, 2 SM 1 P-rec | 2, 5 cm Axilla ± periareolar; 5 cm lateral chest for SM | Skin pulled up with muscle retractor (retromammary route) | Tunnel technique, harmonic scalpel |

2008 | Ito et al. | 33 | In situ/Early BC (2 postCHT) 51 m FU | SM + SLN ± AD + P-rec | 5 cm axilla + breast skin (site of biopsy optival trocar) | Dissection balloon | Tunnel technique, harmonic scalpel |

2008 | Yamaguchi et al. | 21 | BC (no further data) | SM + Rec | 8 cm axilla or inframammary fold | Dissection balloon | No data |

2009 | Fan et al. | 43 | BC T < 3 cm (ok postCHT) 6-48 m FU | SM + AD + P-rec | Three 0, 5 cm incisions (superior, lateral and inferior breast edge) | CO2 insufflation 8 mmHg | Lipolysis solution, liposuction, electric hook |

2009 | Nakajimaet et al. | 244 | 65 m FU BC | BCS + Flap reconstruction | Axilla for lateral Q; | Hirotech external retractor | Tunnel technique, electric scalpel |

Circumareolar for internal Q | |||||||

2009 | Sakomoto et al. | 89 | BC | NSM—No rec in most pts | 3–5 cm Axilla and periareolar | External retractor for face lifting | Tunnel technique, Powerstar scissors |

2012 | Ferrari A, Sgarella A, Zonta s. | 40 | BC and RR | NSM + P-rec;SNB ± AD | 3–4 cm Axilla | 1. External retractor 2. Single-port CO2 insufflation (BESS) | Harmonic scalpel firstly; than radiophrequency dissector (Ligasure) |

In 1997, Yamagata and Iwai [38] reported on endoscopic partial mastectomy and axillary dissection for breast cancer. The access to the breast was represented by an incision around the areola; they performed partial mastectomy using a lifting system, and axillary lymph node dissection under gas insufflation after blunt dissection using a balloon system. The average operation time was 158 min, and blood loss was 25–250 g.

In 1998, Tamaki et al. reported on the preliminary results of video-assisted partial mastectomy performed on a patient with a small breast cancer [39]. A working space was created by subcutaneous dissection using a special endoscope-retractor system and bipolar scissors. A wide excision of the tumor was performed endoscopically through a single small wound in the axilla, and total clearance of the axillary nodes from the same wound with the naked eye.

Kitamura et al. in 1998 [40] proposed a technique that was the merger of the previous experiences: in fact, he realized the dissection of the breast by means of a balloon and then he used the CO2 insufflation at low pressure in order to maintaining the working space wide open. He applied three endoscopic port, one 12 mm trocar and two 5 mm trocars placed on the mid axillary line for excising benign tumors in a small series of patients [37]. He introduced the use of harmonic scalpel both for tissue dissection and hemostasis.

Ishiguro et al. [41] reported a similar surgery in 1999. Although this technique proved to have greater cosmetic advantages over those obtained by routine open surgery, the lengthy operation time could not be disregarded.

To overcome this problem, Tamaki et al. [42] moved the primary incision from the axilla to the periareolar region [42]. The mean total operation time was reduced from 387 to 241 min, and the partial glandectomy itself was performed in 87 min on average. In the latter cases, a sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed through an adjunctive small incision made in the axilla. In case of metastatic sentinel node demonstrated by frozen sections, full axillary dissection was performed with the naked eye from the same wound enlarged to a length of 5 cm, such as in routine breast surgery.

Another interesting variant technique has been proposed by Osanai et al. [43], who performed tumorectomy for benign nodules approaching from the retromammary space. The advantage of the procedure could be represented by less injury to the skin such as burns and numbness. However, this approach would be rather difficult to perform for a large mass or for a tumor located on the surface of the gland.

It should be noted that all these previous reports describing endoscopic breast surgery techniques aimed at the partial removal of the gland affected by cancer, except for Kitamura et al. who realized a total removal of the breast; however, the indications in this case were limited to benign disease. This was mainly due to the fact that SM, either open or video-assisted as proposed in the early 1990s [44, 45], was not (and it is still not) world-wide considered an oncologically safe procedure in the field of breast cancer surgery.

Experiences reported in the first decade of the present millennium include series of endoscopic both BCS and SM for breast cancer, by applying technical approach already described in a variant of combinations.

The evolution of endoscopic BCS evolved from very small series without follow-up [37–39] to the paper of Yamashita and Shimizu [46], who reported on 80 cases of BCS via retromammary route. However, the most important experience appeared in the literature compared more recently, in 2009, when Nakajima and Colleagues [47] reported a series of 244 patients who underwent endoscopic BCS with immediate autologous tissue reconstruction. (Fig. 1.5) While they observed high patient satisfaction, after a mean follow-up of 65.3 months the local recurrence rate of 5.3 % and DFS-OS were similar to the results of conventional BCS. These data raised some interest in the field of endoscopic breast surgery, even if limited to BCS technique.

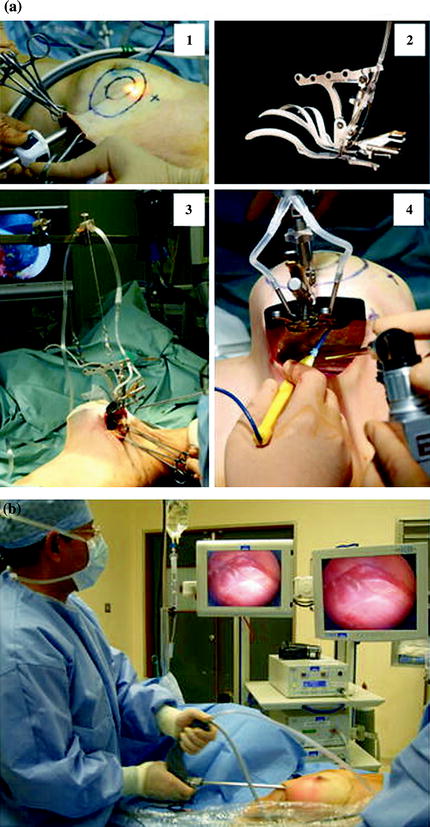

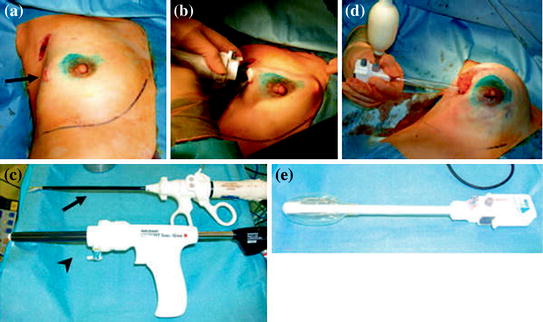

Fig. 1.5

Video-assisted nipple sparing mastectomy as proposed by Nakajima et al. [47] (a) Subcutaneous tunneling method and lifting method. 1 Separation between breast gland and skin under video guidance using the subcutaneous tunneling method, 2 HIROTECH retractor, 3 separation between breast gland and skin under video guidance, 4 separation between breast gland and pectoralis major muscle under video guidance from the mid axillary incision using the lifting method. (b) Intra operative setting of the operative theatre [85]

On the other hand, the field of endoscopic-assisted mastectomy increasingly raised more interest than endoscopic BCS, due to the attractive promise to totally remove the breast gland without scar on the skin and immediate restoring of female body image. However, as in open surgery, leaving the NAC was not already considered an oncologically safe option.

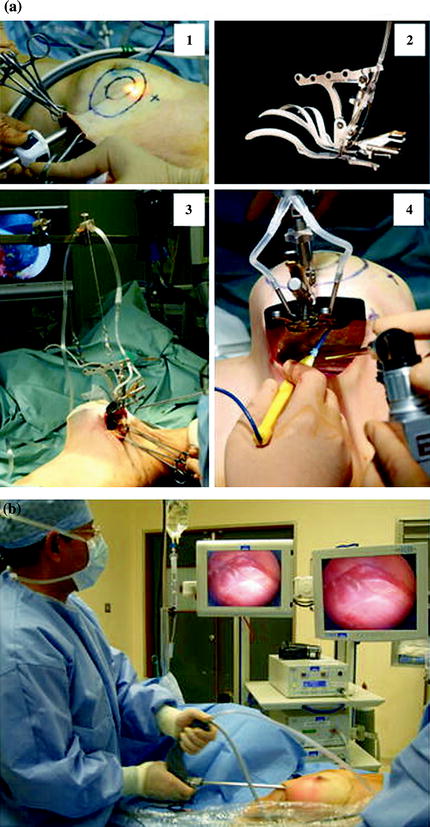

The first series of SM for breast cancer started to compare in the new millennium. In 2001, Sawai et al. [48] described a video-assisted SM and immediate reconstruction with the latissimus dorsi muscle. They removed both the mammary gland and the axillary lymph nodes endoscopically via a 5 cm long skin incision in the midaxillary line. While oncological safeness of the procedure remained questionable, their surgery demonstrated a great cosmetic benefit as compared to conventional mastectomy (Fig. 1.6).

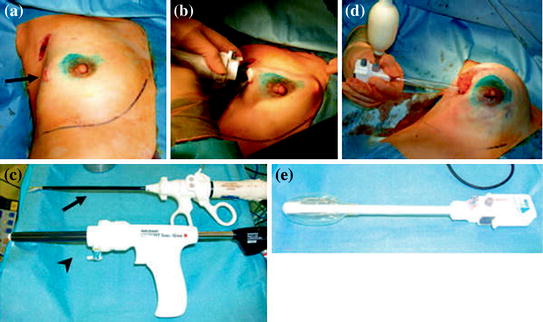

Fig. 1.6

Video-assisted nipple sparing mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy performed in the early 2000s by Ito et Al. (a), visualization trocar is inserted through the axillary incision which had been used to conduct SLNB, and a skin flap is created (b), harmonic scalpel (arrow) and visualized trocar (arrowhead) (c), using a dissection balloon the breast tissue is dissected off the pectoralis fascia (d), the dissection balloon (e) [85]

In 2002, Kitamura et al. [49] presented a series of 21 patients who underwent a video-assisted SM and immediate prosthetic reconstruction again through the axilla (6 cm access), with the aid of CO2 insufflation. He was the first to give a follow-up, even if 19 months long only. In few years, other small series of endoscopic SM with immediate reconstruction for BC were reported by Nakajima et al. in 2002 [50], Ho et al. in 2002 [51], Yamashita and Shimizu in 2006 [52], Ito et al. in 2008 [53], Yamaguchi et al. in 2008 [54], and Fan et al. in 2009 [55]. The latter Author reported the most numerous series (43 patients) with a follow-up ranging from 6 to 48 months, which suggested a safe short-term outcome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree