2 History of reconstructive and aesthetic surgery

Synopsis

History shows that almost every possible local flap has been described in the past and that the ingenuity of plastic surgeons was unlimited.

History shows that almost every possible local flap has been described in the past and that the ingenuity of plastic surgeons was unlimited.

The lesson drawn from history reveals that the so-called new flaps are variations of what has already been published.

The lesson drawn from history reveals that the so-called new flaps are variations of what has already been published.

We have to be humble and recognize that “nothing is new under the sun.”

We have to be humble and recognize that “nothing is new under the sun.”

Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545–1597), from Bologna, Italy, defined plastic surgery as the art devoted to repairing congenital or acquired defects (“to restore what Nature has given and chance has taken away”), and which has as its primary goal the aim of correcting a functional impairment, but also re-establishing an appearance as close as possible to normality (“the main purpose of this procedure – he writes – is not the restoration of the original beauty of the face, but rather the rehabilitation of the part in question”).1 The term “plastic” comes from the Greek πλαστικóς (plasticós), moldable.

Origin of plastic surgery

The distant past

However, this must have been quite complex without appropriate tools, in the presence of hemorrhage and without anesthesia. There is no documentation of stitching of wounds among primitive people.2 We may extrapolate from what was reported in ancient Hindu medicine, where wound edges were sewn with simple means like fibers or strips of tendon, or pinned together using insect mandibles.

In Ancient Egypt

We are well informed about Egyptian surgery thanks to the Smyth papyrus, the most ancient medical text. The papyrus is a later transcription (about 1650 bc) of an original manuscript dating from the Old Kingdom (between 3000 and 2500 bc). It describes 48 surgical cases, including wounds, fractures, dislocations, sores, and tumors, and suggests their potential management. Fresh wounds were treated conservatively with the application of grease and honey using linen and swabs. Adhesive strips of cloth, stitches or a combination of clamp and stitches were advocated to bring together the margins of the wound. A surgical knife was never mentioned, as wounds already existed in the cases presented.2 Treatment of nasal fractures is accurately explained. First, clots should be removed from the inside of the nostrils, then the bony fragments repositioned; two stiff rolls of linen were applied externally “by which the nose is held fast” and finally “two plugs of linen saturated with grease placed into the nostrils.”3

In Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is the region between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates (now approximately Iraq) where Sumerian civilization was born. Medicine was well developed, although strongly influenced by astrology and divination. During excavations of the Nineveh palace, a great library containing more than 30 000 clay tablets with cuneiform inscriptions was discovered, 800 of them of a medical nature. They were written about 600 bc, although the text dates from around 2000 bc. The tablets of interest for plastic surgery are few and concern wound healing or congenital anomalies. “If a man is sick with a blow on the cheek, pound together turpentine, tamarisk, daisy, flour of Inninnu (…) mix in milk and beer in a small copper pan; spread on skin and he shall recover.”4 Another tablet suggests the use of a dressing with oil for an open wound.

Monsters (congenital malformations) were considered important in predicting future events and in determining their course. “When a woman gives birth to an infant (…) whose nostrils are absent, the country will be in affliction, and the house of the man ruined; that has no tongue the house of the man will be ruined; that has no lips affliction will strike the land and the house of the man will be destroyed.”5 Interestingly, surgery is never mentioned in clay tablets, although surgery was certainly performed. In the King Hammurabi Code,2 dating from about 1700 bc, surgical malpractice was recognized with precise laws: “If a physician carried out a major operation on a seignior with a bronze lancet and has caused the seignior’s death or he opened the eye socket of a seignior and has destroyed the seignior eye, they shall cut off his hand.” “If a physician carried out a major operation on a commoner’s slave with a bronze lancet and has caused [his] death, he shall make good slave for slave.”

In India

In India, amputation of the nose was rather common and repair was carried out by the Koomas, a low caste of priests, or, according to others, a guild of potters. In the Áyurvédam, the Indian sacred book of knowledge which deals with medicine, the missing portions of the nose were reconstructed using local flaps transposed from the cheek. An accurate description of blunt (yantra) and sharp (sastra) instruments necessary to perform surgical operations in general and rhinoplasty in particular is supplied.6

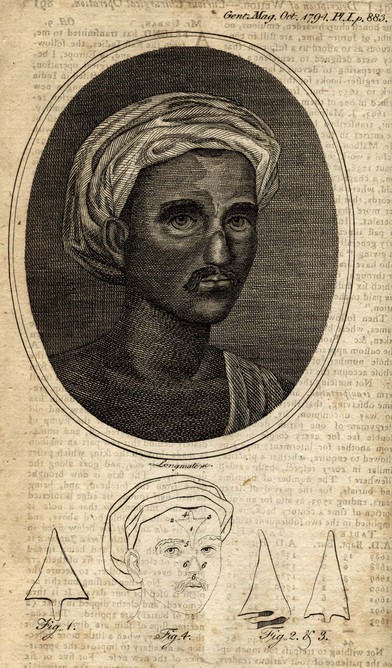

It is not possible either to establish the exact date of the work (it is thought to have been written about 600 bc), or to prove that Sushruta, the author, was one man. On the contrary, there is evidence that over the centuries various Indian surgeons contributed to describe the procedures included in the book. When was the forehead skin used? There is no mention of it. In the second half of the 17th century, the Venetian adventurer Nicolò Manuzzi (1639–1717) wrote a manuscript about the Moghul empire in which an account of forehead rhinoplasty is supplied. Regrettably the manuscript, kept in the Marciana Library at Venice, was not published until 1907.7 Information on the forehead flap in nasal reconstruction only reached the western world at the end of the 18th century, thanks to a letter signed BL, addressed to Mr. Urban, editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine, and published in October 1794 (Fig. 2.1).8

Fig. 2.1 Indian forehead flap nasal reconstruction.

(Reproduced from BL. Letter to the editor. Gentleman’s Magazine 1794;64:891–892.)

In Greece

About 70 medical treatises, assembled during the Alexandrian era (third century ad), were attributed to Hippocrates. They form the so-called Corpus Hippocraticum. Whether Hippocrates himself is the author of the Corpus and these works are authentic has been the matter of great dispute and controversy.9 The Corpus contains manuals, lectures, research, philosophical thoughts, and essays on different topics of medicine, without any logical order and even with significant contradictions among them. The works of Hippocrates were true best-sellers, reprinted numerous times over the centuries. The first printed edition of the Opera omnia (Complete Works) was issued in Latin in Rome in 1525, and in Greek in Venice in 1526 by the Aldine Press.

In Rome

The two most representative figures of Roman medicine were Celsus and Galen.

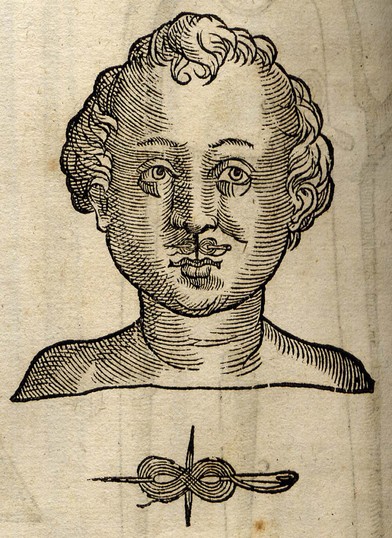

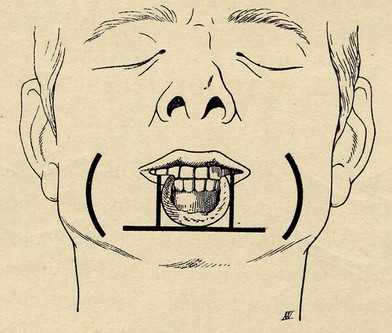

Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 bc–50 ad) was probably not a physician, but a writer from a noble family and the author, in about 30 ad, of De Medicina (On Medicine) in eight volumes. In book seven, chapter nine, vessel ligature and lithotomy as well as lip closure (cleft lip or lip tumor) by means of flaps are reported. It explains how “defects of the ears, lips and nose can be cured” (curta in auribus, labrisque ac naribus, quomodo sarciri et curare possint), followed by a description of wound closure by advancement flap.10 “The defect should be converted into a square (in quadratum redigere). Then, from the inner angles transverse incisions are made (lineas transversas incidere), so that the part on one side is fully divided from that on the opposite side.” “After that, the tissues which have been undermined, are brought together” (in unum adducere). “If this is not possible two additional semilunar incisions are made at some distance from the original (ultra lineas, quas ante fecimus, alias duas lunatas et ad piagam conversas immittere), but only sectioning the outer skin. […] These latter incisions enable the parts to be easily brought together without using any traction” (Fig. 2.2). Celsus holds a key role in the history of plastic surgery, as he is considered the earliest writer on this topic. He is responsible for introducing the four cardinal signs of acute inflammation, “redness and swelling with heat and pain” (rubor et tumor, cum calore et dolore). A copy of Celsus’s manuscript was discovered in Milan in 1443, and printed for the first time in 1478 in Florence.11 De Medicina went through more than 50 editions.

Fig. 2.2 Lip repair according to Celsus.

(Reproduced from Nélaton C, Ombredanne L. Les Autoplasties. Paris, Steinheil, 1907.)

Plastic surgery after the decline of the Roman Empire

Byzantine surgery

Oribasius (325–403 ad) wrote a collection of medical texts entitled Synagogae Medicae in which reconstructive procedures for cheek, nose, ears, and eyebrow defects are described.12 Paulus of Aegina (625–690 ad), surgeon and obstetrician, was the author of a medical encyclopedia (Epitome) in seven volumes. In book 6, which deals with surgery, a description of tracheotomy, tonsillectomy, and lip repair is supplied.13,14 “Defects [Greek, colobomata] of the lips and ears are treated in this way. First the skin is freed on the underside. Then the edges of the wound are brought together and the callosity is removed. Finally, stitches holding them into position are applied.” This technique closely resembles that of Celsus.

The Middle Ages

Arabian surgery

Arabian medical writers came from different nations, such as Persia, Syria, and Spain. Their only common denominator was the language. The most representative figure was Abū-l-Qāsim or Albucasis (c. 936–1013 ad), whose famous treatise, Al Tasrif (On Surgery), was translated into Latin and first published in 1500. It was the first independent surgical treatise ever written in detail. It included more than 200 illustrations of surgical instruments, such as tongue depressor, tooth extractor, hooks, and cauteries, most invented by Albucasis himself, with an explanation of their use.15 Like most Arabian surgeons, Albucasis was a proponent of cautery, for different clinical applications and the management of wounds and cleft lip. He was the first to use a syringe with a piston.

The rise of the universities

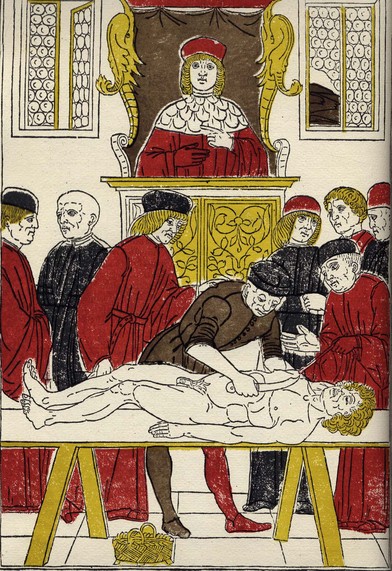

The founding of the universities is one of the most important events in the Middle Age and a key factor in the development of modern culture. Originally, universitas denoted an aggregation of masters (magistri), students, or both, and the primary goal was teaching philosophy and theology. Lessons were practiced in the house of the masters or in small rooms. Students sat on the floor, whereas the professor was in the chair. The oldest university, at least in Europe, was Bologna, established in 1088, followed by Paris, Oxford, and Montpellier. In Bologna medicine was taught and cadaver dissection was accepted, thus significantly contributing to the development of anatomy. Mondino de’ Luzzi (1270–1326) was the first anatomist to lecture directly in front of the cadaver (Fig. 2.3). As anatomists were also surgeons, such as Henry of Mondeville (1260–1320) or Guy of Chauliac (1300–1368), surgery was part of the teaching of anatomy.

The Renaissance

Renaissance surgery

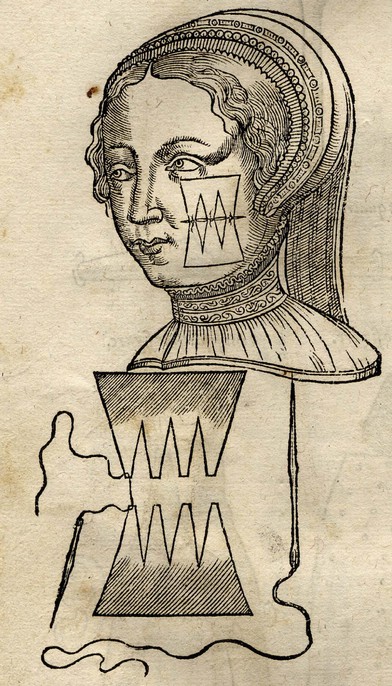

One of the greatest surgical figures of the Renaissance was the Frenchman Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) (Fig. 2.4). A humble but very talented barber surgeon, Paré amassed considerable experience from his tireless work in the battlefields. He disputed the common belief that gunshot wounds were poisoned and required the barbaric practice of wound-cleansing using hot cautery or pouring boiling oil into the wound. He applied a paste of egg yolk instead, mixed with oil of roses and turpentine, to patients’ great relief. In 1545, he published a treatise on gunshot wounds, demonstrating that the use of cautery was unnecessary (La méthode de traicter les playes). He wrote extensively on surgery and his works are collected in Les Oeuvres, published in 1575.16 To demonstrate relationships between anatomy and surgery, he borrowed images from De Humani Corporis Fabrica, issued a few years earlier, in 1543, by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564). He sutured cleft lip, whereas he closed the cleft of the palate using obturators (Fig. 2.5). To approximate scars he stitched adhesive on the outside of the wound margins (Fig. 2.6), and supported Tagliacozzi’s work on nasal reconstruction.

Nasal reconstruction in the western world

In the late 15th century, nasal reconstruction was resumed by Vincenzo Vianeo in Calabria (southern Italy). His sons Pietro (about 1510–1571) and Paolo (about 1505–1560) established a flourishing clinic for rhinoplasty in Tropea (Calabria). Evidence of their reconstructive work comes from the Bolognese army surgeon Leonardo Fioravanti (1517–1588) (Fig. 2.7), who assisted in Vianeo’s operations and published an accurate report in Il Tesoro della Vita Humana (Treasure of Human Life) issued in Venice in 1570.17

Then follows the description of the arm flap procedure.

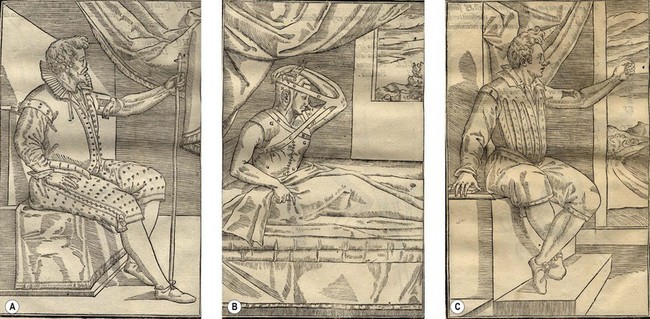

Possibly Fioravanti’s book came under the eyes of Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1544–1599) from Bologna, Professor of Surgery at Bologna University, who successfully applied the technique on some patients. In 1597, he published in Venice a textbook De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem (On the Surgery of Injuries by Grafting),1,18 in which the nasal reconstruction operation is shown step by step and skillfully illustrated. The instruments necessary for the operation are presented first, followed by the indications, flap outlined on the arm, flap inset, the bandage necessary to secure the arm into position, flap severed, trimmed, outcome of nasal repair, as well as different clinical applications for lip and ear (Fig. 2.8). The book was well received and was reprinted in a pocket edition at Frankfurt the following year, directed specifically at military surgeons who were often confronted with the problems of nasal repair in the battlefields.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree