CHAPTER 69 High lateral tension abdominoplasty

History

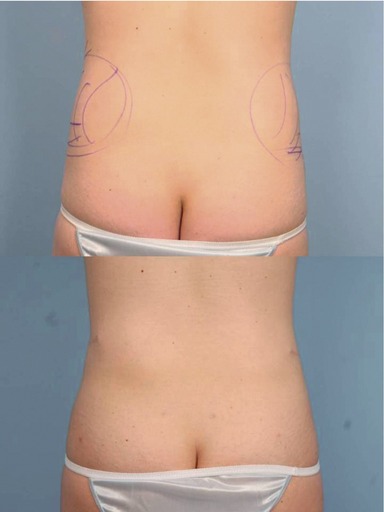

The HLT is not just an abdominoplasty; it is a powerful lower body lifting procedure, creating improvement not just of the abdomen, but to the mons, inguinal region, proximal thighs, and even the buttocks. Even posture can be improved (Figs 69.1, 69.2).

Physical evaluation

• Vertical skin laxity: The signatures of the high lateral tension abdominoplasty is to place the highest tension on the lateral portion of the incision, such that the central third of the incision is nearly in apposition after closure of each lateral third. This often means that the old umbilical site does not get excised, leaving a vertical scar from its closure. While this usually heals well, and accepting the presence of this scar may be considered part and parcel with being a true HLT “purist”, this scar does not always heal perfectly, and many patients and surgeons indeed do want to avoid it. There are occasions preoperatively when the surgeon cannot be certain as to whether the old site will be able to be excised, without tension but if there is any question, the patient should be warned that there are three choices: proceeding with a classically marked HLT and accepting that vertical scar if it is necessitated for proper skin tension of excision intraoperatively, perhaps locating the entire incision more superiorly in order to increase the likelihood of getting out the old umbilical site, or simply not doing an HLT, but resecting as much tissue as necessary centrally in order to remove the site, even if this means distorting or raising the height of the mons.

• Extent of skin laxity: Many patients today ask for a “mini” tummy tuck, wanting the horizontal extent of the incision to be as short as possible, perhaps even as narrow as their C-section scar. It is rare to find women whose laxity is so centrally located that such a short scar removes all of the laxity that is troubling to the patient while creating a smooth contour to the abdomen, and the patient should always be evaluated sitting upright, as this demonstrates the extent to which the laxity extends laterally. Patients can understand that if the laxity extends to the mid-axillary line that an incision the width of her previous C-section will fail to correct the lateral laxity. Even compared to the standard abdominoplasty, the HLT does require a wider incision. That is because the standard tummy tuck is essentially an exercise in “excising the umbilicus”; the width of the incision is determined according to one parameter: how much is necessary to remove that vertical excess without creating a dog-ear. But the HLT considers that lateral excess the most important area for excision. By pulling down and out laterally, a greater degree of flattening of the epigastrium occurs than pulling simply straight inferiorly. This can easily be demonstrated to a patient by creation of downward tension on the epigastrium by pinching between the umbilicus and just above the mons, and contrasting that with the greater improvement that occurs to the epigastrium by simultaneously pinching lateral, angled down and out, so that the epigastrium is being pulled in two directions. The greatest laxity on the trunk of the post-partum or weight loss patient is also laterally, so this area needs the greatest amount of excision.

• Skin quality and texture: Just like with a mastopexy, after skin is removed, the same skin that stretched once and was damaged remains behind. The ultimate quality of the result and appearance will be based upon the patient’s own skin, for which we have little if any control. It is important to asses the skin in order to give the patient expectations as to what their particular outcome is likely to be. Do stretch marks still exist superior to the likely line of resection so that many will remain, or are they likely to all be excised? Is the skin thin and/or sun-damaged, likely to reloosen to a significant degree or have notable lines or wrinkles? These issues must all be addressed with the patient preoperatively in order to set their expectations, and patients should further realize that there is no preoperative test that can predict how their particular skin will hold up after surgery; the best a surgeon can do is offer them an educated guess. The presence of pre-existing abdominal scars must be assessed as they may have affected blood supply in such a way so as to necessitate modification of the HLT design, or to limit undermining even more than usual. Occasionally the scar is adherent to the underlying abdominal wall and consideration needs to be given to whether the scar needs to be freed to allow transfer of tightening forces beyond it, or whether such a maneuver would compromise blood supply. There are also sometimes transverse lines of adhesion, usually between umbilicus and xyphoid between the midline and the anterior axillary line that prevent transference of pull from the abdominoplasty to the tissues cephalad to it. It can take substantial undermining to free these up, and in doing so the blood supply to the flap can be compromised. These issues need to be discussed with the patient preoperatively.

• Excess fat within flap: The HLT allows for safe suctioning of the abdominoplasty flap. The flap should be evaluated not just for the presence of significant subcutaneous fat, but for the extent to which this fat is proportional to the patient’s overall body habitus. Most important is noting the thickness at the expected level of flap transection relative to where that tissue will be sewn inferiorly. It is frequently much thicker superiorly, and liposuction of the flap should be considered to create a smooth transition. I tend to suction abdominaplasty flaps only occasionally. The patient population I predominantly see is thin. Moreover, though liposuction of the flap can be done safely, it does seem to increase the likelihood of seroma formation and prolong recovery.

• Excess fat in contiguous areas: When a patient seems to have a large amount of fat in their abdominal flap, there is usually an even greater amount of fat in the pubic area or the posterior iliac crest area. Too much is made of liposuctioning of abdominal fat within the flap. Oftentimes, there is not enough to remove to make a significant difference in the appearance. Usually, the hips contain substantially more fat in proportion to the abdomen. If there is a lot to remove in the abdomen, there is usually more in the hips or the thighs, and it is important to look at those areas and consider treating them, lest the surgeon create a disharmonious proportion. With the abdomen flattened from an abdominoplasty, the width that results from excess hip fat can be very apparent. In fact, by tightening the abdomen, the width of the hip area can appear to increase following an abdominoplasty (Fig. 69.3). Narrowing the waist through suction of the posterior hip roll can dramatically improve the appearance of the abdomen. Similarly, excess fat in the mons area is often not noted preoperatively. Either the abdomen may be protuberant or there may be tissue overhanging the waist. After a smooth and flatter abdomen, the mons can protrude in clothing and be disconcerting. This can be treated with liposuction at the time of abdominoplasty and this area should be assessed for this preoperatively.

• Rectus diastasis/hernia: The patient should be examined standing, sitting, and laying back flat while raising her shoulders up, as in doing a partial sit-up. This is a good way to test for a rectus diastasis. From this position, one can take the patient’s hands and show them the gap that exists between their muscles. Some patients will comment that they need “to work out more.” But they need to be reassured that exercise will only increase the strength of the muscles; only surgery can bring them back together. I always discuss with patients that they have an option of whether or not to plicate any diastasis. While the plication can substantially improve the outcome, so too does it lengthen the recovery and make it more uncomfortable. The umbilicus is always assessed for the presence of a fascial defect that may need to be repaired either separately or at the time of abdominoplasty. The patient should also be examined in profile with her arms at her sides and above her head, asking her to allow her abdominal musculature to relax. During plication, it is all too tempting to tighten her as much as possible from pubis to xyphoid; more important is to assess the patient’s laxity and preplan where the abdomen needs to be tightened to create the most attractive contour.

• Intra-abdominal fat: Pressure from the internal organs including intra-abdominal fat puts pressure on any repair that is done of the rectus diastasis. While it is possible for there to be relapse in any situation, this is certainly exacerbated in cases in which there is the greatest degree of intra-abdominal fat. This is important because it might weigh on your choice as to whether or not there is enough of a benefit from plication to make it worth the additional recovery. Also, it helps to warn patients about an increased possibility of the repair loosening and restretching with time.

Anatomy

The skin/adipose layer

It also must be appreciated that there is both horizontal and vertical excess of the skin/subcutaneous fat layer. The horizontal scar of an abdominoplasty obviously reduces the vertical excess, but what about the horizontal excess? Usually the body is wider at the height of the lower abdominoplasty incision than it is at the upper abdominoplasty incision, so that when the edges are closed, the horizontal excess is apparently eliminated. But there is not a significant change in width of the abdomen from the level of the xyphoid down to about the level of the umbilicus; in fact, the body often narrows. What this means is that the tissue that is transferred down from the upper to the mid-abdomen during a tummy tuck develops even greater horizontal laxity when a traditional abdominoplasty is done, as the incision is relatively parallel to the ground and the greatest pull is straight inferiorly. But with the HLT, the lateral limbs of the final closure diverge superiorly in an oblique direction, and they hold the greatest amount of tension. This serves to excise that horizontal redundancy in the epigastrium, thereby flattening it and significantly improving the abdominal contour.