Herpes Simplex: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are common worldwide and are caused by two closely related types of HSV. Their main clinical manifestations are mucocutaneous infections, with HSV type 1 (HSV-1) being mostly associated with orofacial disease, whereas HSV type 2 (HSV-2) is usually associated with genital and perigenital infection.

The incidence of primary infection with HSV-1, which is responsible for the vast majority of recurring labial herpes, is greatest during childhood, when 30%–60% of children are exposed to the virus. Rates of infection with HSV-1 increase with age and reduced socioeconomic status, the majority of persons age 30 or older are seropositive for HSV-1.1,2 From 20% to 40% of the population have had episodes of herpes labialis.3 The frequency of recurrent episodes is extremely variable, and, in some studies, averages about once per year,4 but there is evidence that the frequency and severity of recurrent HSV-1 disease decrease over time.

Acquisition of HSV-2 correlates with sexual behavior and the prevalence of the infection in the pool of one’s potential sexual partners. Antibodies to HSV-2 are rare in people before the onset of intimate sexual activity and rise steadily thereafter. HSV-2 seroprevalence in the United States is 22% in persons 12 years of age or older.5 The rate of HSV-2 seropositivity declined in the United States from 21% in 1988–1994 to 17% in 1999–2004, and rate of HSV-1 seropositivity declined from 62% to 58% during the same period.6

Although most patients infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2 are asymptomatic, they still can transmit the virus. Studies using DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays show that rates of detecting HSV-2 DNA in genital secretions of people who have never recognized herpes outbreaks (asymptomatic persons) are similar to the rates of shedding viral DNA in people who have experienced symptomatic genital herpes but who are not symptomatic at the moment of testing (subclinical shedding).7 In one study, 21% of genital swabs were positive for HSV-2 by PCR and 12% of oral swabs were positive for HSV-1 PCR in HSV-2 and HSV-1 seropositive persons, respectively.8 It is estimated that more than 70% of transmission of HSV-2 is associated with asymptomatic and subclinical reactivation and shedding. The rate of transmission is no higher is persons with frequent symptomatic recurrences than those with infrequent recurrences.9 The average risk of transmission for couples discordant for genital herpes (i.e., one partner has genital herpes and the other does not) varies from 5% to 10% per year.10,11 As with other sexually transmitted infections, the rate of acquisition of HSV-2 infection is higher for women than for men (6.8 vs. 4.4 cases per 100 person-years; relative risk, 1.55). Asymptomatic HSV-2 infection is more common among men and persons who are also seropositive for HSV-1, suggesting that prior infection with HSV-1 reduces one’s likelihood of experiencing symptomatic HSV-2 infection.12 Studies have shown that genital HSV infections significantly increase the risk for acquisition and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Randomized trials with acyclovir reduced the frequency of genital ulcers and slightly reduced HIV viral loads, but did not reduce transmission of HIV.13,14

Etiology and Pathogenesis

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are members of the Herpesviridae family, a group of lipid-enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses. Both serotypes of HSV are members of the α-Herpesviridae virus subfamily. α-Herpesviruses infect multiple cell types in culture, grow rapidly, and efficiently destroy the host cells. Infection in the natural host is characterized by lesions in the epidermis, often involving mucosal surfaces, with spread of virus to the nervous system and establishment of latent infections in neurons, from which virus periodically reactivates. HSV-1 and HSV-2 have a high degree of genetic and antigenic homology. An analysis of herpesvirus phylogeny estimated that the two HSV types diverged from an ancestral protoherpesvirus approximately 8 million years ago.15

Herpesvirus replication is a carefully regulated process. Shortly after infection, immediate-early genes are transcribed whose proteins upregulate expression of early proteins that are required for genome replication. The late [HSV-2→HSV] genes encode virion structural components including the glycoproteins.

In vivo, HSV infections can be divided into three stages: (1) acute infection, (2) establishment and maintenance of the latency, and (3) reactivation of virus. During acute infection, virus replicates at the site of inoculation on mucocutaneous surfaces, resulting in primary lesions from which virus rapidly spreads to infect sensory nerve terminals, where it travels by retrograde axonal transport to neuronal nuclei in regional sensory ganglia. In a subset of infected neurons, a latent infection is established in which viral DNA is maintained as an episome and HSV gene expression is severely restricted: of all of the viral genes, only one is abundantly transcribed during latency. In the last stage, replication reactivates with concomitant anterograde axonal transport of newly assembled virus to a peripheral site, at or near the original portal of entry (see eFig. 193-0.1).

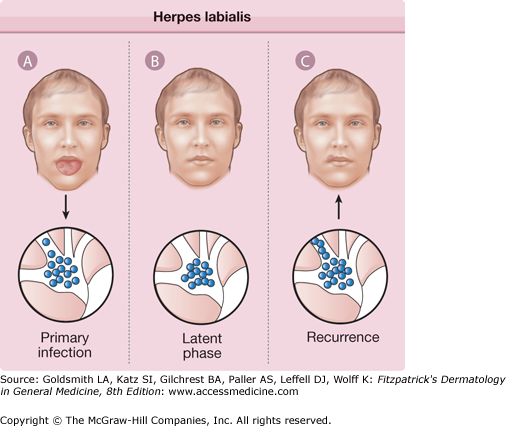

eFigure 193-0.1

Herpes labialis. A. With primary herpes simplex virus infection, virus replicates in the oropharyngeal epithelium and ascends peripheral sensory nerves into the trigeminal ganglion. B. Herpes simplex virus persists in a latent phase within the trigeminal ganglion for the life of the individual. C. Various stimuli initiate reactivation of latent virus, which then descends sensory nerves to the lips or perioral skin, resulting in recurrent herpes labialis.

HSV-1 reactivates most efficiently and frequently from trigeminal ganglia, whereas HSV-2 reactivates primarily from sacral ganglia. The rate of reactivation of HSV appears to be influenced by the quantity of latent viral DNA in the ganglia.16 Reactivation is induced in experimentally infected animals by exposure to ultraviolet irradiation, by hyperthermia, by local trauma, and by other physiologic stressors.

Host immunity to HSV clearly influences the risk of acquiring the infection, the severity of disease, and the frequency of recurrences. The risk of severe HSV disease and the recurrence rate correlates with the level of cellular immune competence of the host. Patients with mild decreases in cellular immunity may experience only an increased number of recurrences and a slower resolution of lesions, whereas severely compromised patients are more likely to develop disseminated, chronic, or drug-resistant infections.

Studies of humans and mice have implicated a role for both CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte subsets, natural killer cells, and inflammatory cytokines like interferon-γ in mediating protection against HSV. However, the contribution of each cell subset and cytokine in the control of HSV infection has not been clearly defined. Innate immunity is also important and polymorphisms in TLR2 are associated with increased rates of genital lesions in seropositive persons.17

Patients with defects in humoral immunity have no increase in HSV disease severity, but the humoral immune response is important in reducing virus titers at the site of inoculation and in regional neural tissues during primary infection. Animals are effectively protected from disseminated and neurologic disease by passive transfer of polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies and by antibody responses elicited actively through vaccination. Moreover, the transfer of HSV-specific antibodies from the mother to the child is a key factor in protecting against neonatal herpes.

The mechanisms of immunity required to sustain latency and limit reactivation of HSV are less clear. There is evidence that constant immune surveillance and engagement are required to maintain latency, mainly by HSV-specific CD8+ lymphocytes and low levels of viral proteins produced in neurons.18 T cells reactive to HSV-1 are clustered around latently infected neurons in ganglia from HSV-1 seropositive persons.19 HSV-specific CD8+ lymphocytes localize to site of reactivation and persist in the skin for weeks after lesions are cleared.20

Clinical Findings

The clinical manifestations of HSV infection depend on the site of infection and, as indicated in Immune Response (above), the immune status of the host. Primary infections with HSV, namely those that develop in persons without preexisting immunity to either HSV-1 or HSV-2, are usually more severe, frequently with systemic signs and symptoms, and they have a higher rate of complications, than recurrent episodes.

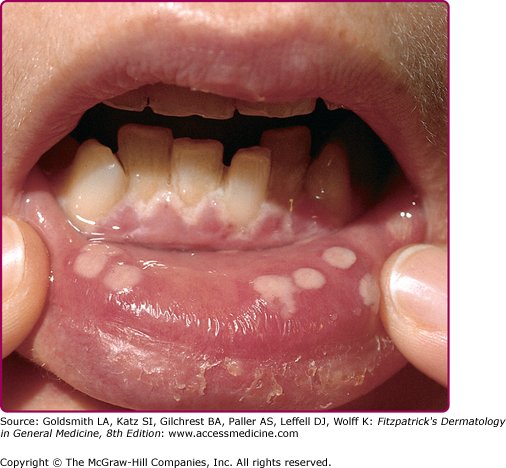

Herpetic gingivostomatitis (Fig. 193-1) and pharyngitis are most commonly associated with a primary HSV-1 infection. The symptoms of primary oral herpes may resemble those of aphthous stomatitis and include ulcerative lesions involving the hard and soft palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa, as well as neighboring facial areas. Patients with pharyngitis exhibit ulcerative and exudative lesions of the posterior pharynx that can be difficult to differentiate from streptococcal pharyngitis. Other common symptoms are fever, malaise, salivation, myalgias, pain on swallowing, irritability, and cervical adenopathy.

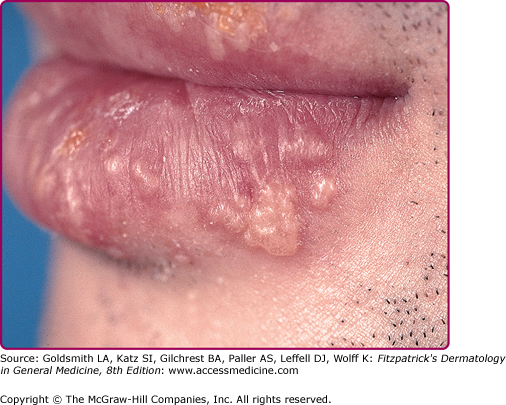

Reactivation of virus from these primary infections involves the perioral facial area, mainly the lips, with the outer one-third of the lower lip being the most commonly affected (Fig. 193-2 and see eFig. 193-2.1). Other facial locations include the nose, chin, and cheek, and account for less than 10% of the cases (Fig. 193-3). Two-thirds of labial lesions involve the vermilion border, whereas the rest occur at the junction of the border with the skin. In patients with frequent recurrences, lesions may differ slightly in location with each episode. Immunocompetent patients tend not to experience recurrent intraoral lesions, but can present with clusters of tiny vesicles and ulcers, or linear fissures on the gingivae and anterior hard palate that are mildly symptomatic. Prodromal symptoms precede herpes labialis in 45%–60% of episodes. Patients experience pain, burning, or itching at the site of the subsequent eruption. Even in the immunocompetent patient, the severity of recurrent herpes labialis is extremely variable and may vary from that of prodromal symptoms alone without the subsequent development of lesions (aborted episodes) to extensive disease induced by severe local sunburn.

The progression of the classical herpes lesions has been divided according to the following stages based on their features: prodromal, erythema, and papule (the developmental stages); vesicle, ulcer, and hard crust (disease stages); followed by dry flaking and residual swelling (resolution stages). The lesions usually resolve within 5–15 days.

Trigger factors for oral herpes recurrences include emotional stress, illness, exposure to sun, trauma, fatigue, menses, chapped lips, and the season of the year.21 Other well-documented triggers include exposure to ultraviolet irradiation, trigeminal nerve surgery, oral trauma, epidural administration of morphine, and abrasive, laser, and chemical facial cosmetic procedures. The exact mechanism by which these diverse factors trigger HSV reactivation is unknown.

HSV-2 causes a primary orofacial infection that is indistinguishable from that associated with HSV-1 except that it is usually in adolescents and young adults and following genital–oral contact. Moreover, HSV-2 orolabial infections are 120 times less likely to reactivate than is orolabial HSV-1 disease. For the differential diagnosis of orofacial herpes see Box 193-1.

Disease | Differences from Orolabial Herpes |

Aphthous ulcers | Not preceded by vesicles, only on mucosa |

Syphilis | Painless, not preceded by vesicles |

Herpangina | Posterior portion of mouth (soft palate, tonsils) |

Stevens Johnson syndrome | Disseminated lesions |

Disease | Differences from Genital Herpes |

Chancroid | Deep ulceration with exudate |

Syphilis | Painless, not preceded by vesicles |

Lymphogranuloma venereum | Painless ulcer, unimpressive primary lesions |

Granuloma inguinale | Painless ulcer, exuberant lesions |

Genital herpes is the major clinical presentation of HSV-2 infection, but it may also result from HSV-1 in 10%–40% of the cases, primarily following oral–genital contact.22 Because of their epidemiology, acquisition of HSV-1 in a person with prior HSV-2 infection is unusual, but HSV-2 acquisition in the presence of previous HSV-1 infection is common, and infection of the genital tract with both HSV-1 and HSV-2 has been described. Patients with previously known HSV-1 genital infection who develop frequent genital herpes recurrences should be tested for HSV-2 infection.23 Viremia occurs in about 25% of persons during primary genital herpes.24

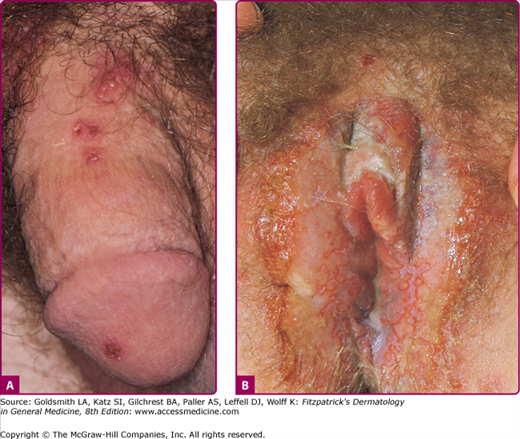

The clinical course of acute first-episode genital herpes among patients with HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections is similar. These infections are associated with extensive genital lesions in different stages of evolution, including vesicles, pustules, and erythematous ulcers that may require 2–3 weeks to resolve (Fig. 193-4). In males, lesions commonly occur on the glans penis or the penile shaft; in females, lesions may involve the vulva, perineum, buttocks, vagina, or cervix. There is accompanying pain, itching, dysuria, vaginal and urethral discharge, and tender inguinal lymphadenopathy. Systemic signs and symptoms are common and include fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias. Herpetic sacral radiculomyelitis, with urinary retention, neuralgias, and constipation, can occur. HSV cervicitis occurs in more than 80% of women with primary infection. It can present as purulent or bloody vaginal discharge, and examination reveals areas of diffuse or focal friability and redness, extensive ulcerative lesions of the exocervix, or, rarely, necrotic cervicitis. Cervical discharge is usually mucoid, but it is occasionally mucopurulent.

The rates of recurrence for genital HSV-2 infections vary greatly among individuals and over time within the same individual. Infections caused by HSV-2 reactivate approximately 16 times more frequently than HSV-1 genital infections, and average 3–4 times per year, but may appear virtually weekly.3 Recurrences tend to be more frequent in the first months to years after first infection. The classical clinical manifestations of recurrent HSV-2 infection include multiple small but grouped vesicular lesions in the genital area (Fig. 193-5), but it can occur anywhere in the perigenital region, including the abdomen, groin, buttocks, and thighs (Fig. 193-6), and the lesions may recur at the same site or change location. The recurrence of genital lesions may be heralded by a prodrome of tenderness, itching, burning, or tingling, and the outbreaks are less severe than primary infection. Without treatment, the lesions usually heal in 6–10 days. Herpetic cervicitis is less common in recurrent disease, occurring in 12% of patients. It may present without external lesions. Signs and symptoms that are less classical for genital HSV infection, and which may divert one from the correct diagnosis include small erythematous lesions, fissures, pruritus, and urinary symptoms. HSV can cause urethritis, usually manifested only as a clear mucoid discharge, dysuria, and frequency. Occasionally, HSV can be associated with endometritis, salpingitis, or prostatitis. Symptomatic or asymptomatic rectal and perianal infections are common. Herpetic proctitis presents with anorectal pain, anorectal discharge, tenesmus, and constipation, with ulcerative lesions of the distal rectal mucosa. Genital herpes can recur at nongenital sites as well. For the differential diagnosis of genital herpes, see Box 193-1.

Figure 193-5

A. Genital herpes: recurrent infection of the penis. Group of vesicles with early central crusting on a red base arising on the shaft of the penis. This “textbook” presentation, however, is much less common than small asymptomatic erosions or fissures. B. Genital herpes: recurrent vulvar infection. Large, painful erosions on the labia. Extensive lesions such as these are uncommon in recurrent genital herpes in an otherwise healthy individual.

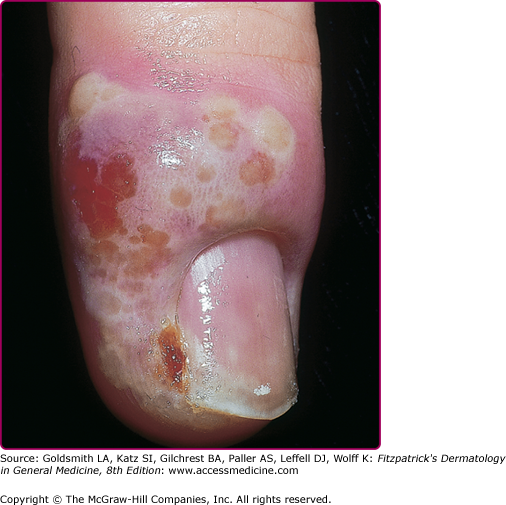

HSV can infect any skin site (Fig. 193-6). The common theme among virtually all of these cutaneous presentations is the requirement that virus has penetrated otherwise normal and well-keratinized tissues. Herpetic whitlow (Fig. 193-7) is infection of the fingers by HSV acquired by direct inoculation or by direct spread from mucosal sites at the time of primary infection. Thus, a typical presentation of whitlow would be in children who suck their fingers during a primary gingivostomatitis outbreak. It is also a well-documented occupational hazard for medical personnel. It is usually caused by HSV-1, but HSV-2 whitlow may develop as a manifestation of primary inoculation following manual–genital contact with an infected partner. The infected region becomes erythematous and edematous. Lesions are usually present at the fingertip and can be pustular and very painful. Fever and local lymphadenopathy are common. Whitlow is often misdiagnosed as a bacterial paronychial infection, but the surgical drainage, often needed for a bacterial infection, is unnecessary and potentially harmful, while antiviral therapy speeds healing. Whitlow may recur.

Cutaneous herpes can be transmitted between athletes involved in contact sports, such as wrestling (herpes gladiatorum) and rugby (herpes rugbiaforum or scrum pox), and may occur as outbreaks or small epidemics among team members. In these instances, multiple herpetic lesions may appear across the thorax, ears, face, arms, and hands, in which infection is facilitated by trauma to the normally keratinized skin during sport activities (Fig. 193-8A). Concomitant ocular herpes can occur.

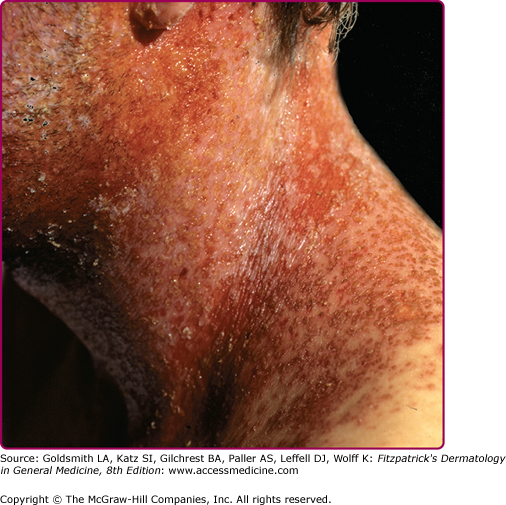

Eczema herpeticum (Kaposi varicelliform eruption; Fig. 193-8B and eFig. 193-8.1) results from widespread infection following inoculation of virus to skin damaged by eczema. It is usually a manifestation of primary HSV-1 infection in a child with atopic dermatitis, and the expression of cathelicidins in the skin may be a factor in controlling susceptibility to eczema herpeticum in these patients.25 Mycosis fungoides, Sèzary syndrome, Darier disease, various bullous diseases of the skin (particularly if patients are receiving immunosuppressive therapy), and burns of second or third degree can also be complicated by cutaneous dissemination of HSV. The severity of eczema herpeticum ranges from mild to fatal, with mortality rates of up to 10% being reported before antiviral therapy was available. Mortality was usually primarily caused by bacterial superinfection and bacteremia. Common pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Pseudomonas. In a typical severe primary attack, several days after exposure vesicles develop in large numbers over areas of active or recently healed atopic dermatitis, particularly the face, and continue to appear in crops for several more days. The vesicles become pustular and markedly umbilicated. Patients commonly have high fever and adenopathy. Viremia with infection of internal organs can be fatal. Recurrences are usually far milder than these first infections. Arriving at the correct diagnosis can be delayed because of secondary impetigo involving the lesions, but it always should be considered in children with infected eczema, particularly if the child is more systemically ill than one might anticipate with impetigo. Eczema herpeticum of the young infant is a medical emergency, and early treatment with acyclovir can prove lifesaving.

Recurrent HSV infection is the most common precipitating event in cases of recurrent erythema multiforme (see Chapter 39). HSV-associated erythema multiforme is usually an acute, self-limited, recurrent disease. The duration of the disease is usually about 3 weeks. The lesions are usually disseminated and symmetric, occurring on acral extremities and the face, and there is grouping of the lesions over the elbow and knees, as well as nail fold involvement. Mucosal involvement is usually mild and restricted to the mouth. Constitutional symptoms are rare, and the skin lesions heal without scarring.

Laboratory Tests

The method of choice for diagnosis of HSV infection depends on the clinical presentation. In many instances, the history and clinical findings may be sufficient, but the social, emotional, and therapeutic implications of a diagnosis dictate that it be confirmed by laboratory testing when possible. For patients with lesions, virus can be isolated in cell culture. In culture, HSV causes typical cytopathic effects, and most specimens will prove positive within 48–96 hours after inoculation. The sensitivity of the culture depends on the quantity of the virus in the specimen. Even in the most experienced centers, only approximately 60%–70% of fresh genital lesions are culture-positive. Isolation of the virus is most successful when lesions are cultured during their vesicular stage and when specimens are taken from immunocompromised patients or from patients suffering from a primary infection.

PCR is more sensitive than viral isolation and has become the preferred method for diagnosis. PCR has been extensively used for the diagnosis of central nervous system infections and in neonatal herpes. It is also useful for the detection of HSV in late-stage ulcerative lesions. Both viral culture and PCR assays enable typing of the isolate as HSV-1 or HSV-2. This information helps to predict the frequency of reactivation after a first-episode of HSV infection.

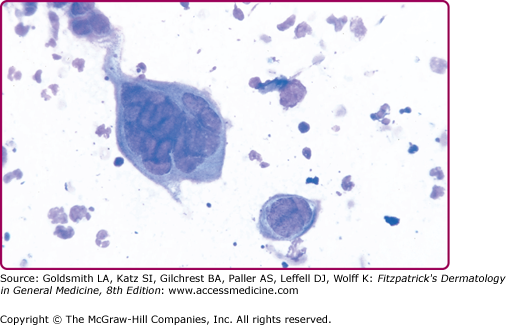

Direct fluorescent antibody staining of lesion scrapings and antigen detection assays can also be used but sensitivity is lower than viral culture.26 The Tzanck smear can be helpful in the rapid diagnosis of herpesvirus infections, but it is less sensitive than culture and staining with fluorescent antibody, with positive results in fewer than 40% of culture-proven cases. It is performed by scraping the base of a freshly ruptured vesicle and staining the slides with Giemsa or Wright stain (the Papanicolaou staining method can also be used), followed by examination for the multinucleated giant cells that are diagnostic of herpetic infection (Fig. 193-9). Both HSV and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) will cause these changes. In skin biopsy specimens, epithelial cells are enlarged, swollen, and often separated. Multinucleated cells with intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Cowdry type A inclusions) can be seen.

Figure 193-9

Herpes simplex virus: positive Tzanck smear. A giant, multinucleated keratinocyte on a Giemsa-stained smear obtained from a vesicle base. Compare size of the giant cell to that of neutrophils also seen in this smear. Another smaller multinucleated acantholytic keratinocyte is seen as well as acantholytic keratinocytes. Identical findings are present in lesions caused by varicella-zoster virus.

Serologic detection of antibodies to HSV can be helpful in certain settings, but the results are often misinterpreted. Its main function is in differentiating a primary episode from a recurrent infection (Table 193-1). A positive serologic test result can be useful in patients with recurrent, genital lesions that are not present at times of examination and, therefore, a positive culture cannot be obtained. Serologic testing can also be helpful for counseling patients with initial episodes of disease and their partners, especially during pregnancy, and in counseling partners of patients with genital herpes about their risk of acquiring HSV.

Classification | Virus Isolated | Serology (Acute) | Serology (Convalescent) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HSV-1 | HSV-2 | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | ||

Primary HSV-1 | HSV-1 | − | − | + | − |

Primary HSV-2 | HSV-2 | − | − | − | + |

Primary HSV-1 plus previous HSV-2 infectiona | HSV-1 | − | + | + | + |

Primary HSV-2 plus previous HSV-1 infection | HSV-2 | + | − | + | + |

Recurrent HSV-1 | HSV-1 | + | − or + | + | − or + |

Recurrent HSV-2 | HSV-2 | − or + | + | − or + | + |

Type-specific serologic assays based on antigenic differences between HSV-1 and HSV-2 glycoprotein G, are available.27 These tests should be used by practitioners who are prepared to counsel patients about the meaning of the test results in terms of the natural history of the disease, available treatment regimens, disease transmission, and the emotional and social implications of the diagnosis.28

Complications

All manifestations of HSV infection seen in the immunocompetent host can also be seen in immunocompromised patients but they are usually more severe, more extensive, and difficult to treat; for many of them, recurrences are more frequent as well. Patients with defects of T cell immunity, such as those with AIDS or transplant recipients, are at particular risk for progressive mucocutaneous or visceral infections, but the degree of dissemination depends on the level of immunodeficiency of the host. Recurrent and persistent ulcerative HSV lesions are among the most common and defining opportunistic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Genital herpes is very common in patients with HIV and can be persistent and severe. Oropharyngeal HSV in immunocompromised patients can present with widespread involvement of skin (Fig. 193-10), the mucosa, and extremely painful, friable, hemorrhagic, and necrotic lesions, similar to mucositis caused by cytotoxic agents. The lesions can spread locally to involve the esophagus. Esophagitis presents with odynophagia, dysphagia, substernal pain, and multiple ulcerative lesions. Esophagitis can also arise directly by reactivation of HSV and its spread to the esophagus via the vagus nerve. Tracheobronchitis can also occur by spreading of the virus from oropharyngeal HSV.

HSV can reactivate from visceral ganglia of the autonomic nervous system or disseminate hematogenously to other visceral organs (causing pneumonitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, or meningitis) and other portions of the gastrointestinal tract, as well as causing adrenal necrosis. Most of these severe infections are caused by HSV-1, but HSV-2 can do so as well. Few are ever diagnosed except at autopsy.

HSV is a leading cause of recurrent keratoconjunctivitis and it is associated with corneal opacification and visual loss. It is usually caused by HSV-1, except in neonates in whom HSV-2 is more prevalent. The majority of HSV eye disease is caused by reactivation of the virus in the trigeminal ganglia, but primary infections of the eye can also occur. Usually, the initial manifestation of herpetic eye disease is a superficial infection of the eyelids and conjunctiva (blepharoconjunctivitis), or corneal surface (dendritic or geographic epithelial ulcer with pain and blurred vision). Deeper involvement of the cornea (stromal keratitis) or anterior uvea (iritis) represents more serious forms of the disease and can cause permanent visual loss. Acute retinal necrosis is a rare but rapidly progressive disease characterized by retinal arteriolar sheathing, uveitis, and peripheral retinal opacification with variable pain and visual loss. Bilateral involvement may occur, and retinal detachment is common. It is usually associated with HSV-1 infection, but HSV-2 retinitis has been described, and VZV causes a similar process.29