Gonorrhea, Mycoplasma, and Vaginosis: Introduction

|

Gonorrhea

More than 600,000 people are estimated to acquire new gonococcal infections in the United States yearly according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although only about half are actually reported through the public health system. This makes gonorrhea the second most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States, second only to chlamydia. The rate of new infections declined after the implementation of a national gonorrhea control program in the United States during the mid-1970s and continued to decrease through the late 1990s. It has since stabilized at near 100 cases per 100,000 population.1 The prevalence of infection may have decreased due to sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening programs that have incorporated immediate, on-site, single-dose treatment, when indicated. Safer sex practices in response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic may also be a factor contributing to the decline of new gonorrheal infections. The highest rate of reported gonococcal infections is among sexually active teenagers and young adults, aged 15–24. There is notable ethnic disparity, with the reported gonorrhea rate in African-Americans being twenty times higher and in Hispanics twice as high when compared to Caucasians.1 Such racial disparity is multifactorial and may be due to differences in accessibility to health care, lack of use of available resources, and sexual partner preferences. Risk factors for acquisition of gonorrheal infection include new or multiple sex partners, younger age, unmarried status, commercial sex work, minority ethnicity, substance and alcohol abuse, lower socioeconomic and educational levels, inconsistent condom use, and any previous STD infection. Prior gonorrhea is an especially important risk factor for acquisition of a new gonococcal infection, as recidivism is particularly common.2 As is true of most STDs, alcohol ingestion to the point of inebriation is associated with risky sexual behavior, including unprotected intercourse and sex with multiple partners, and is thus a major factor in acquisition of gonorrhea.3

Since the 1980s, prevalence rates among men and women have been similar in all age categories, although for any given age range, the prevalence will be slightly higher in women. The highest rates in women are for those between the ages of 15 and 19 years and in men between the ages of 20 and 24 years.1 However, one should never exclude the diagnosis of any STD based upon age alone. A relatively high divorce rate and the wide availability of drugs to treat erectile dysfunction have both contributed to a resurgence of STDs (including gonorrhea) amongst those middle-aged and older individuals living in industrialized countries.4 A higher rate of new infections among men having sex with men (MSM) has also been reported in some major cities.5

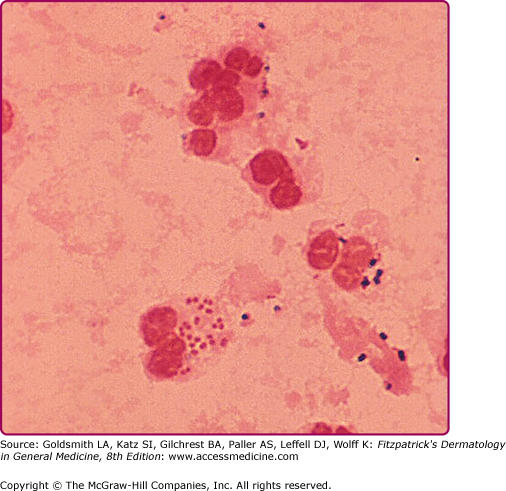

Albert Ludwig Sigismund Neisser first discovered the causative agent of gonorrhea in 1879. This infection is due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative, aerobic coccus-shaped bacterium typically found in pairs. The organisms are usually visualized intracellularly, located within polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Fig. 205-1). Gonorrhea is acquired through sexual contact, or, much less commonly, as a result of poor hygiene or the complementary/alternative “medical” use of urine. It can also be transmitted vertically from mother to child during normal vaginal birth, characteristically causing an inflammatory eye infection (ophthalmia neonatorum).

Pathogenesis involves bacterial attachment to columnar epithelial cells via pili or fimbriae. The most common sites of attachment include the mucosal cells of the male and female urogenital tracts. Outer membrane proteins, PilC and Opa, on the bacteria aid in attachment and local invasion. Invasion is mediated by bacterial adhesins and sphingomyelinase, which contribute to the process of endocytosis. Gonococci also induce upregulated target cell integrins, which prevent mucosal cell shedding, a natural defense mechanism. Certain gonococcal strains produce immunoglobulin A proteases that cleave the heavy chain of the human immunoglobulin and block the host’s normal bactericidal immune response. Once inside the cell, the organism undergoes replication and can grow in both aerobic and anaerobic environments. After cellular invasion, the organism replicates and proliferates locally, inducing an inflammatory response. Outside the cell, the bacteria are susceptible to temperature changes, ultraviolet light, drying, and other environmental factors. The outer membrane contains lipooligosaccharide endotoxin, which is released by the bacteria during periods of rapid growth and contributes to its pathogenesis in disseminated infection. Delays in proper antibiotic treatment, physiologic changes in host defenses, resistance to immune responses, and highly virulent strains of bacteria contribute to hematogenous spread and disseminated infection. Humans are the only natural hosts of N. gonorrhoeae.6

N. gonorrhoeae infection tends to involve mucous membranes predominantly lined by columnar epithelial cells. The urethra, cervix, rectum, pharynx, and conjunctiva are the areas most commonly involved.

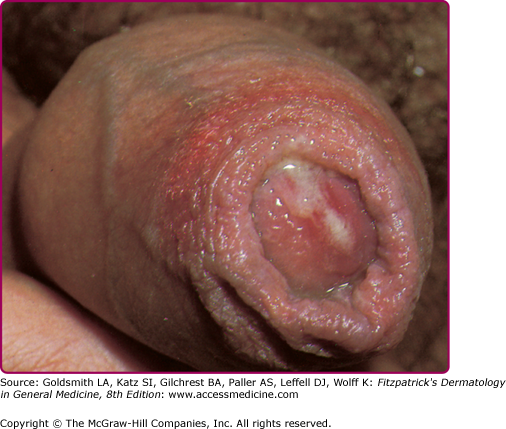

The incubation period in men is typically from 2 to 8 days, although it may rarely be longer since most infections are symptomatic by 2 weeks following exposure. Only about 10% of infections are asymptomatic in men. The most common manifestation of gonococcal infection in men is urethritis, characterized by a spontaneous, often profuse, cloudy or purulent discharge from the penile meatus. (Fig. 205-2). Mucosal membrane inflammation in the anterior urethra leads to pain or burning upon urination and meatal erythema and swelling (Fig. 205-3). In some cases, there is so much soft tissue inflammation that the entire distal penis becomes swollen, so-called “bull head clap.” (Fig. 205-4) Testicular pain and swelling may indicate epididymitis or orchitis and may be the only presenting symptom. However, epididymitis is more commonly caused by Chlamydia trachomatis or by combined infection with N. gonorrhoeae. There have been rare instances of genital skin furuncles due to gonorrhea.7

Proctitis is a manifestation of gonococcal infection manifesting in those who practice unprotected anoreceptive intercourse. Thus, it is most common in MSM. Symptoms may include a rectal mucopurulent discharge, pain on defecation, constipation, and tenesmus. As a result of gonococcal proctitis, MSM are at a higher risk of acquiring HIV infection due to both damaged anorectal epithelial integrity and local recruitment of HIV-target cell types (CCR5/CD4+ T cells and DC-SIGN+ dendritic cells).8

Pharyngitis caused by N. gonorrhoeae was once thought to be rare. However, the commonplace practice of fellatio amongst heterosexual adolescents and young adults, as well as among MSM, often in lieu of penetrative intercourse, has made pharyngeal gonorrhea much more common.9 While it may be asymptomatic, pharyngeal disease may serve as a source for disseminated gonococcal disease. When present, symptoms range from cervical lymphadenopathy and mild-to-moderate pharyngeal erythema to severe ulceration with pseudomembrane formation.10

Fifty percent of women infected with N. gonorrhoeae are asymptomatic. Appropriate screening, prompt diagnosis, and treatment are crucial in women due to serious complications that can result in sterility. The endocervix is a common site of local infection. Symptoms of urethritis include mucopurulent discharge, vaginal pruritus, and dysuria. However, vaginitis does not occur except in prepuberal girls or postmenopausal women because the vaginal epithelium of sexually mature women does not support growth of N. gonorrhoeae. Other sites of infection include Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands, which results is swelling and tenderness.7 Organisms may invade the upper genital tract, including the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, resulting in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

PID occurs in about 10%–40% of uncomplicated gonorrheal infections in women and is characterized by fever, lower abdominal pain, back pain, vomiting, vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia, and adnexal or cervical tenderness during movement associated with a pelvic examination. Sequelae of untreated infection include tubo-ovarian abscesses, subsequent ectopic pregnancies, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility due to chronic inflammation with resultant scarring. Symptoms tend to occur or worsen at the time of menses and cannot be distinguished from nongonococcal etiologies.11,12 Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, involving inflammation of the liver capsule, is associated with genitourinary tract infection and may be present in up to one-fourth of women with PID caused by either N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis. Presenting symptoms include right upper quadrant pain and tenderness with abnormal liver function tests.13 This syndrome must be distinguished from acute viral hepatitis.

Women may also develop proctitis through autoinoculation from cervical discharge or as a result of direct contact from an infected partner’s penile secretions. As is true in men, symptoms may include rectal mucopurulent discharge, pain on defecation, constipation, and tenesmus. The incidence of gonococcal pharyngitis is higher than that in men due to the common practice of fellatio, especially among adolescents. It is estimated that, in adolescent women, 11%–26% of cases of gonorrhea are comprised solely of asymptomatic pharyngeal infection.9

Neonates may acquire N. gonorrhoeae during passage through the birth canal from contact with infected secretions. Such ocular infections are known as ophthalmia neonatorum, and are characterized by profuse, purulent ocular discharge.14 and can lead to severe corneal perforation or scarring. Most states, by law, require the prophylactic use of silver nitrate drops, erythromycin, or tetracycline ophthalmic ointment for prevention of ophthalmia neonatorum. However, the efficacy of prophylactic ocular antibiotics has been recently questioned, and its use in low-risk patient populations may someday be discontinued.15 Pharyngeal or genital gonococcal infection in children is often a sign of sexual abuse and warrants further investigation.14

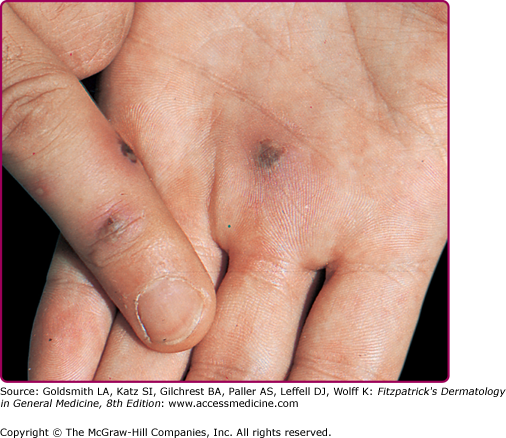

Spread of infection from the primary site of inoculation to other parts of the body through the bloodstream leads to disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), also known as gonococcemia. Disseminated disease occurs in 0.5%–3% of cases and is associated with a classic triad of dermatitis, migratory polyarthritis, and tenosynovitis. Pain and swelling may occur in a single joint or in multiple joints asymmetrically. True septic arthritis due to gonorrhea is more typically monoarticular or pauciarticular, whereas polyarticular disease is most often associated with active bacteremia.16

Skin findings consist of small- to medium-sized macules or, most typically, hemorrhagic vesicopustules on an erythematous base located on palms and soles (Fig. 205-5) or on the trunk and elsewhere on the extremities. Skin lesions may develop necrotic centers. The concurrence of some degree of hemorrhage and necrosis led to the term “gun metal gray” to describe the cutaneous lesions of DGI. On the palms and soles, lesions may be tender, but in other sites they tend to be both nonpruritic and painless. Skin lesions disappear after appropriate treatment has been administered. Cutaneous lesions may be present in 40%–70% of cases of disseminated disease. Histologically, perivascular neutrophilia, dermal vasculitis, and epidermal neutrophil infiltration may be seen.

Organisms are Gram-negative, intracellular diplococci visualized microscopically inside polymorphonuclear cells. Because of high specificity (>99%) and sensitivity (>95%), a Gram stain of a urethral specimen that demonstrates polymorphonuclear leukocytes with intracellular Gram-negative diplococci can be considered diagnostic for infection with N. gonorrhoeae in symptomatic men.17 However, because of lower sensitivity, a negative Gram stain can not be considered sufficient for ruling out gonococcal infection in asymptomatic men at high risk for infection. In addition, Gram stains of endocervical specimens, pharyngeal, or rectal specimens also are not sufficient to detect infection, and, therefore, are not recommended.17 Vaginal specimens are never recommended for diagnostic purposes, since the vaginal mucosa resists gonococcal invasion.

Bacterial culture has been the “gold standard” diagnostic test for years, although newer and more specific tests are now being widely used. Culturing N. gonorrhoeae requires media containing heme, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, yeast extract, carbon dioxide, and other supplements required for isolation. Culture can be performed on modified Thayer-Martin medium. In men, culture and Gram stain are performed on secretions or urethral swabs. Endocervical and endourethral specimens for culture and Gram’s stain yield accurate results in women. Cultures on pharyngeal and rectal swabs may also be performed if infection is suspected in these areas.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved certain chemiluminescent DNA probes that can be used on endocervical or urethral specimens for diagnosis of gonorrhea. However, distinguishing gonococcal from nongonococcal infection may be difficult with DNA probes. Newer techniques include the use of nucleic acid amplification tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcription-mediated amplification, and strand displacement amplification on urine or urethral specimens. Overall, nucleic acid amplification tests are highly sensitive and specific and may be able to detect even the presence of one organism.18 However, the precise test considered “optimal” in terms of specificity, sensitivity, practicality, and cost effectiveness remains to be determined and is subject to ongoing controversy.19 Even nucleic acid detection tests may yield false positive and false negative results. In addition, diagnosis via any nonculture method does not allow for antibiotic sensitivity testing.

In DGI, cultures, and if available, nucleic acid amplification testing, should be done on blood, joint fluid, and skin lesions. Synovial fluid from affected joints must be analyzed for cell count, Gram stain, and culture. Of necessity, diagnosis may rely on clinical suspicion and pertinent findings, because tests for DGI yield positive results only in a small number of cases.

Box 205-1 shows the differential diagnosis for all mucosal-oriented venereal diseases.

Localized | Systemic | Always Rule Out |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Permanent sequelae of gonococcal infection in women may be infertility as a result of untreated PID. Untreated DGI can lead to septic arthritis, yielding permanent joint damage. Meningitis and endocarditis are rare manifestations of DGI, which can lead to death or permanent disability due to central nervous system or cardiac damage.

Prognosis is excellent if infection is treated early with appropriate antibiotics. Previously treated gonococcal infection does not reduce the risk of reinfection. DGI has a good prognosis if treated appropriately and before permanent damage to joints or organs occurs.

Ten percent to 30% of people with gonococcal infection are coinfected with Chlamydia. Thus, routine dual therapy with doxycycline or azithromycin has been recommended and shown to be cost effective. Dual therapy also decreases the development of antimicrobial resistance. Box 205-2 shows current CDC recommendations, as revised in 2010, for uncomplicated cervical, urethral, pharyngeal, and rectal gonococcal infections.20 Due to the increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, quinolones are no longer recommended for the routine treatment of any gonococcal infections.21 Spectinomycin, the recommended alternative to cephalosporins, has had an inconsistent history of availability and as of 2010, is not available in the United States. However, dosage regimens for spectinomycin are maintained in Box 205-2 should this situation change in the near future.

Alternate single-dose cephalosporin regimens may be considered on an individual basis, and include: Ceftizoxime 500 mg IM, Cefotaxime 500 mg IM, Cefoxitin 2.0 g IM administered with probenecid 1.0 g PO Some evidence exists that the following single-dose regimens might also be effective: Cefpodoxime 400 mg PO and Cefuroxime axetil 1.0 g

|

Patients with DGI may require hospitalization due to septic arthritis, meningitis, or endocarditis. The recommended regimen for DGI is ceftriaxone, 1 g intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) every 24 hours, continuing for 24–48 hours after improvement is noted. Treatment may then be switched to oral doses of the antibiotics listed in Table 205-1. Treatment of gonococcal meningitis should consist of ceftriaxone, 1–2 g IV every 12 hours for 10–14 days. Therapy for gonococcal infections in neonates is shown in Box 205-3. Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum should be treated with ceftriaxone, 25–50 mg/kg IV or IM, not to exceed 125 mg in a single dose. For treatment regimens of PID and epididymitis, the reader is referred to a CDC Web site.20

| Recommended Regimen | |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 g IM or IV every 24 hours (intravenous route preferred) |

| Alternative Regimens | |

| Cefotaxime | 1 g IV every 8 hours |

| Or | |

| Ceftizoxime | 1 g IV every 8 hours |

| Or | |

| Spectinomycin | 2 g IM every 12 hours |

| Following clinical improvement, parenteral therapy may be switched to oral therapy for seven additional days: | |

| Cefixime | 400 mg BID PO |

| Or | |

| Cefpodoxime | 400 mg BID PO |

|

Sexual partners of those found to have gonococcal infections should be evaluated. However, since this is not always feasible, empiric treatment may be advisable. In general, treatment of partners of female or heterosexual male patients diagnosed with gonorrhea empirically is as or more effective than the traditional reliance on referral, testing and as needed treatment.22 One way of doing this is via expedited partner therapy (having the index patient deliver therapy to the partner); such expedited therapy decreases the risk of persistent or recurrent infection in the index patient.23 No studies have evaluated empiric treatment of gonorrhea (or chlamydia) in MSM. State laws vary with regard to expedited partner therapy and must be considered. Moreover, this type of empiric therapy misses the opportunity to counsel partners and treat comorbid disease, when detected.

Chlamydia

Infection with C. trachomatis is the most common reported STD in the United States, with more than 1.2 million reported cases in 2009.1 Due to a high rate of asymptomatic infection, the prevalence of infection may actually be much higher. The national rate of chlamydial infection is 409.2 per 100,000 population, representing a 3% increase from the prior reporting year.1 This may be as a result of wider screening and more sensitive and specific tests. The highest rates of infection reported are in women between the ages of 15 and 24 years. Following the expanded availability of less invasive urine testing for chlamydia, men are getting evaluated with greater frequency, resulting in an increase of over 45% in the chlamydia rate among men between 2004 and 2009.1 While the overall rate of reported chlamydia among men is lower than among women, the CDC estimates that the actual overall prevalence of chlamydia is similar among men and women. Infection rates among African-Americans have been eight times higher and in Hispanics three times higher than those reported in same-gender Caucasians.1 Chlamydial infection is also disproportionately high among Native American and Eskimo populations. Risk factors are similar to those related to gonococcal infections, and include young age, new or multiple sex partners regardless of age, unprotected sexual intercourse, inconsistent condom use, commercial sex work, and low socioeconomic and educational status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree