Chapter 39 Gluteal contouring and rejuvenation

• Rates of surgical intervention to contour and rejuvenate the gluteal region have been rapidly increasing in recent years.

• The gluteal esthetic has largely been codified and varies across ethnicities.

• A systematic approach to the evaluation of the gluteal region is critical as one designs an appropriate and individualized operative plan.

• Modalities including the utilization of prosthetic implants, liposculpture and autologous tissue flaps may be employed alone or in combination to contour the gluteal region.

• These procedures may be performed safely and reliably if careful attention is paid to patient selection, operative design and technical execution.

• Complications of gluteal contouring procedures are generally infrequent and minor.

Introduction

Evaluation of female beauty and esthetics varies across cultures, but tends to focus on the breast and buttocks as key elements of investigation, evaluation and surgical intervention. Plastic surgical trends have largely focused on the breast; however, over the past 10 years augmentation and rejuvenation of the gluteal region have far outpaced intervention upon the breast and abdominal region. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgery trends, from 2000 to 2010, procedures which aim to enhance the esthetic of the gluteal region, including lower body lifting and specifically buttock lifting, have seen increases of 4550% and 143% respectively.1

Preoperative Preparation

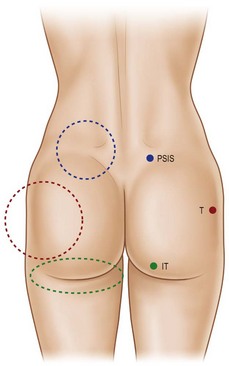

The characteristics of the ideal gluteal esthetic must first be defined prior to the determination of an appropriate surgical plan for the patient presenting for gluteal contouring surgery. The gluteal esthetic was largely codified in 2006 by Cuenca-Guerra and colleagues.2 Their analysis of over 2400 images of the gluteal area revealed four of the most recognizable characteristics of an esthetically pleasing gluteal region: (1) Two mild lateral depressions that correspond to the femoral greater trochanter; (2) A short infragluteal fold lying in the horizontal crease under the ischial tuberosity which does not extend beyond the medial two-thirds of the posterior thigh; (3) Two supragluteal fossettes (or dimples) on either side of the medial sacral crest which correspond to the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS); and (4) A V-shaped crease (sacral triangle) which arises from the proximal end of the gluteal crease and extends toward the sacral fossettes (Fig. 39.1).

It is critical for one to understand the variations across ethnicities in defining gluteal esthetics. Roberts has outlined very specific variations of this basic framework between ethnic groups in the United States.3 The short infragluteal fold, supragluteal fossettes and sacral triangle are generally universally accepted, whereas mild lateral depressions tend not to be preferred by Hispanic or African-Americans. This population tends to prefer a fuller lateral gluteal region along with increased projection compared to Asian-Americans, who prefer a short buttock with a high point of maximum projection. United States Caucasians tend to prefer a more athletic ideal with greater muscular and bony anatomy definition with less anterior-posterior projection.

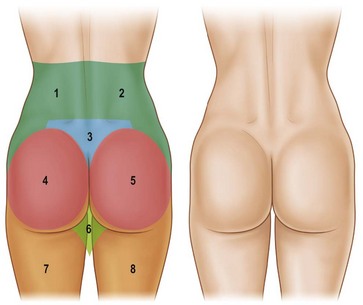

With these regions of a pleasing buttock region defined, one must have a systematic way to define the anatomy of the patient presenting for gluteal contouring. Centeno has described eight esthetic units that must be evaluated in order to design an appropriate, individualized surgical plan.4 From the posterior-anterior view, the gluteal region consists of two symmetrical flank units, a sacral triangle, two symmetrical gluteal units, two symmetrical thigh units, and one infragluteal diamond unit (Fig. 39.2). These regions should be individually considered and addressed in the surgical planning process. The junctions between these units serve as useful sites for incision placement during excisional procedures. Mendieta has subsequently divided these esthetic units into more discrete subunits.5 One must also consider the surrounding regions of the abdomen, anterior thigh, medial thigh, and lateral thigh. Derangement, overcorrection, or undercorrection of these areas may create overall disharmony as the gluteal region is surgically approached.

Proper evaluation of the gluteal region is critical when planning surgical intervention. Mendieta has devised a classification system analyzing the underlying bony framework, gluteus maximus muscle, subcutaneous fat topography and overlying skin to assist in operative planning.5 It is the interplay of these variables that assists in selecting the appropriate procedure on an individual basis.

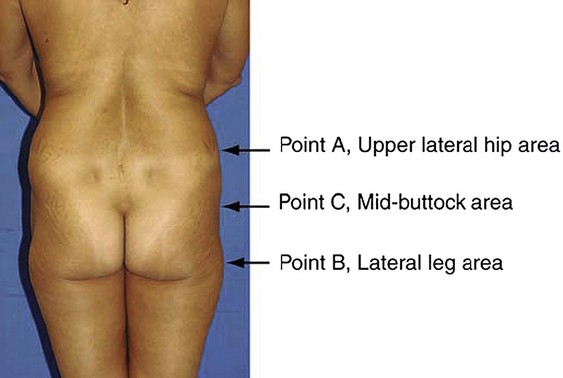

Mendieta begins with classification of the “frame”, which he defines as the bone, skin, and fat of the buttock region. Frame types are defined based on the location of three topographical landmarks: the “A” point representing the most protruding point in the upper lateral hip, the “B” point representing the most protruding point in the lateral thigh, and the “C” point representing the depression at the lateral mid-buttock (Fig. 39.3). The square buttock, most commonly seen, is defined as equal protrusion of points A and B. The round shape is similar, but is characterized as having excess fat deposition at point C. A-shaped frames are characterized as having more fat in the lateral upper thigh (B point); this is contrasted with the V-shaped frame which is characterized as having more fat in the upper lateral hip region (A point). These A-shaped and V-shaped frames have colloquially been referred to as “pear shaped” and “apple shaped”, respectively. Targeted liposculpture tends to be very effective in reshaping these frames to achieve a more esthetically pleasing gluteal region.

FIG. 39.3 Mendieta’s frame evaluation utilizing three critical landmarks.

(Mendieta C. Classification system for gluteal evaluation. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:333–346.)

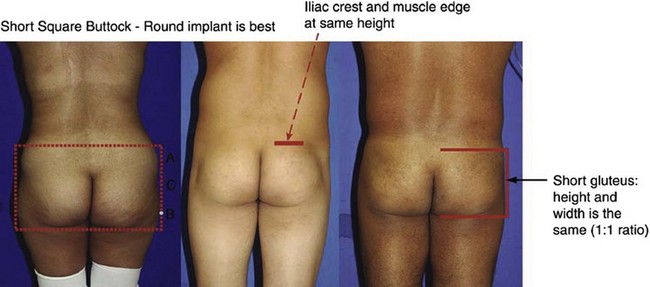

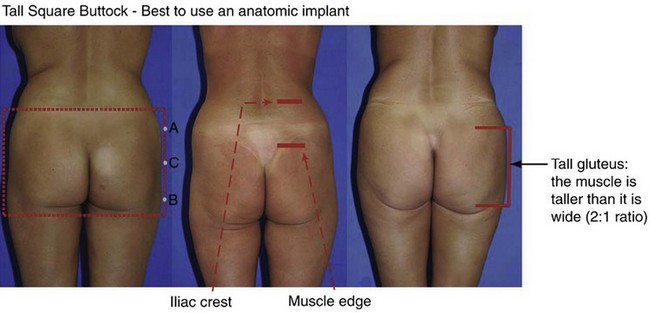

The gluteus maximus muscle can then be evaluated. Mendieta classifies the gluteal musculature based on its height-to-width ratio with 1 : 1 being defined as a short muscle, 2 : 1 being defined as a tall muscle, and those in between defined as an intermediate muscle (Fig. 39.4). This classification scheme is particularly critical when one is evaluating a patient for gluteal implant placement. Patients with short gluteus maximus muscles are best augmented with round implants, whereas those with tall muscles require an anatomic implant. For those with intermediate gluteal muscles, evaluation of projection and shape from a lateral view assists in determining the appropriateness of a round, anatomic or oval implant shape.

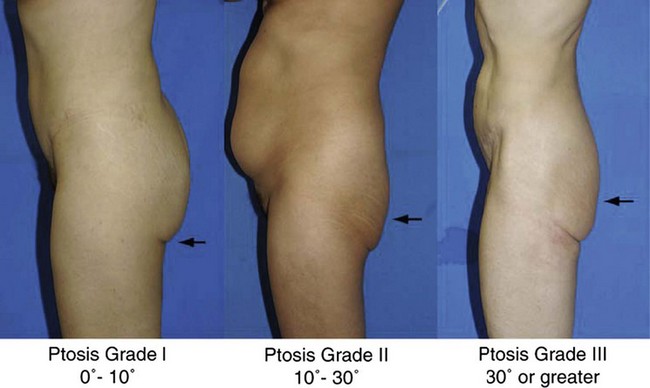

A gluteal ptosis classification scheme has also been devised by Mendieta, which is similar in design to that of breast ptosis described by Regnault.6 Those patients with some buttock volume and skin falling slightly below the infragluteal fold are described as having Grade I ptosis. Patients with an apparent and angular infragluteal fold with skin drooping below it are classified as having Grade II ptosis. Those patients with severe skin laxity, along with a laterally extending infragluteal fold with an angle of greater than 30° are classified as having Grade III ptosis (Fig. 39.5).

Surgical Technique

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – An Overview

Gluteal augmentation for reconstruction was first described by Bartels in 1969.7 Cosmetic correction of lateral gluteal depressions was subsequently undertaken by Cocke and Ricketson in 1973 with their utilization of mammary implants.8 Specific gluteal implants are now available in various shapes and textures. Numerous options for prosthetic implantation exist in Mexico and South America. Cohesive gel implants with a polyurethane textured surface allow implants to have a natural feel with less capsular contracture and a tendency to maintain their position. Unfortunately, the soft solid elastomer prostheses available in the United States are more rigid, leading to increased palpability and firmness.

Subcutaneous implant placement was originally described by Gonzalez-Ulloa.9 This approach has been abandoned secondary to unacceptably high complication rates and utilization of more appropriate tissue planes.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Submuscular Approach

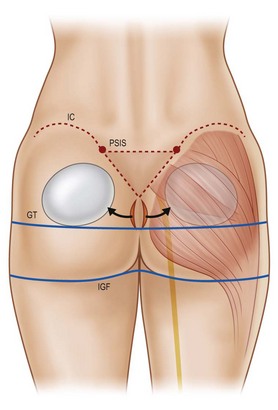

In 1984, Robles and colleagues described gluteal augmentation utilizing the submuscular space.10 This approach successfully addressed the capsular contracture and palpability complications seen with the subcutaneous approach. However, the anatomy of the submuscular space limits the augmentation that may be achieved. Because the sciatic nerve exits on the underside of the piriformis muscle at its inferior border, augmentation is limited to utilization of smaller round implants placed in a more superior location. This results in greater projection in the upper gluteal region with a deficiency in the lower portion (Fig. 39.6). Furthermore, with such superior placement, gluteal ptosis may not be appropriately addressed. Risk of direct injury to the sciatic nerve also accompanies this approach. While this technique may be used today for patients with a well-developed inferior gluteal region requiring upper pole augmentation, it has largely fallen out of favor with the advent of intramuscular and subfascial descriptions.

Prosthetic Gluteal Augmentation – Intramuscular Approach

The intramuscular approach to prosthetic gluteal augmentation provides padding both above and below the gluteal implant. Utilization of this space allows for better inferior placement when compared to the submuscular approach and decreases the risk of injury to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 39.7).

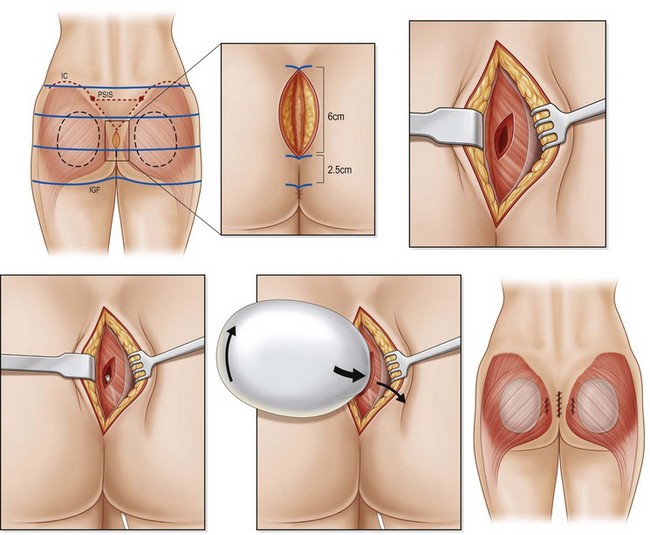

The authors prefer the technique outlined by Mendieta.11 Preoperative Decadron and clindamycin are administered and intermittent pneumatic compression stockings are applied. General anesthesia or epidural placement with IV sedation may be utilized. The patient is placed in the prone jackknife position with the entire gluteal region prepped and draped. A Betadine-soaked gauze is placed over the anus to prevent contamination of the surgical field. While a single midline approach had previously been advocated, two parasacral incisions are now utilized to minimize postoperative wound dehiscence. The midline is marked and two paramedian lines are drawn 1 cm lateral to the midline which curves to follow the upper gluteal curvature superiorly for a total length of 8 cm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree