CHAPTER 70 Gluteal augmentation

History

The norms of beauty for the gluteal region have changed over the centuries, and probably more during the past 10 to 15 years. The Rubenesque curves of the Renaissance are no longer acceptable to many women today. Contemporary women search for an athletic look with well-defined curves in the buttock area. Standards of beauty include a well-projected gluteus and a uniform line that on the lateral view makes a natural curve from the waist to the knee.1

The demand for gluteal augmentation has been growing since the 1960s, even though no surgical technique had been described at that time. The first way to augment the buttocks was with round silicone gel breast implants, but problems related to their use in the buttock region led to the development of implants designed specifically for gluteal augmentation.2 Surgical procedures were then developed to improve the aesthetic results. Gonzalez-Ulloa was one of the first surgeons to reconstruct the gluteal region, either by lifting “sagging” buttocks or placing a subcutaneous implant to augment them.3 With his technique, the aponeurotic expansions running from the gluteal aponeurosis to the dermis must be divided. Following that, the skin is loose and displacement of the implant results in poor aesthetic results. The second generation of implants included Dacron patches on the back. The goal was to affix the implant within the pocket. However, these patches were not sufficient to maintain implant position. Since that time, techniques for gluteal augmentation have progressed through three other anatomic planes: submuscular, intramuscular and subfascial (Fig. 70.1).

In 1984, Robles described the submuscular approach.4 This approach preserved the aponeurotic system that holds the gluteal skin in position. However, it introduced a new anatomical problem with the potential risk of injury to the sciatic nerve. The intramuscular plane was developed by disrupting the gluteal muscle fibers.5,6 The goal was to leave a 3–4 mm thickness of gluteus maximus muscles attached to the aponeurosis. In fact, it is very difficult to estimate the quantity of muscle on top because undermining was done blindly with no anatomic landmarks to guide the dissection. Moreover, the possibility of injuring the sciatic nerve was not totally eliminated and seroma incidence and complication rate are above 30%. To solve problems encountered with other techniques, we sought to identify a new anatomic plane that could hold gluteal implants securely with little morbidity. Extensive anatomic dissections were performed in which we studied the gluteal aponeurosis. Our subfascial technique is based on these anatomic studies.7–10

Physical evaluation

• Candidates: those who lack projection of the gluteal region and desire an improved shape of the gluteus.

• Ideal candidates: thin patients with an athletic build and little or no ptosis; they can obtain spectacular results.

• Overweight patients may also benefit from this technique, but often require a more extensive liposculpture in the same surgery.

• Know in advance the exact measurements of the subfascial space as well as the patient’s expectations to help to determine the implant size.

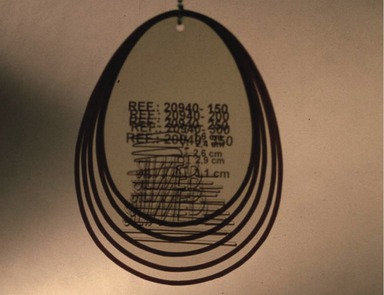

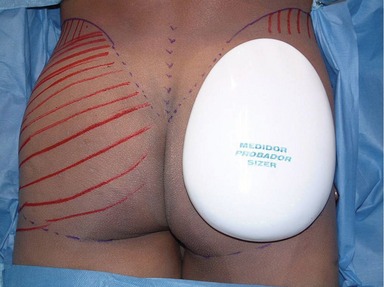

• The most appropriate size of the implant can be selected before surgery using templates.

• Lipodystrophy may be corrected with liposculpture of the neighboring areas.

• Aesthetics of this region include the waist–hip ratio that must be ± 1:1.6.

• Intergluteal sulcus must be in the middle third of the gluteus maximus muscle and about the same size of the lumbosacral–intergluteal sulcus distance.

Technical steps

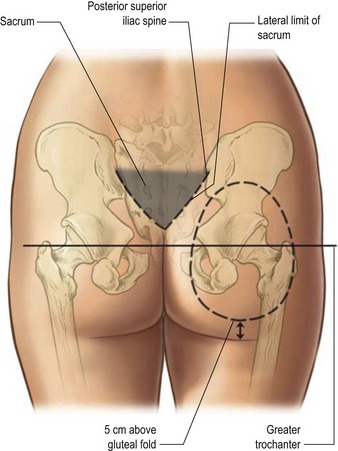

With the patient in the upright position, skin markings are made using a custom-designed template (Fig. 70.2). This template must fit perfectly into the gluteal region leaving 5 cm above the infragluteal sulcus and 2 cm lateral to the external rim of the sacral bone. The sacral triangle must be preserved; it is an important aesthetic landmark of this region. The implant should never be placed on top of the sacral bone. Laterally, the template will extend to the external border of the gluteal region, leaving at least 2 cm from the external line (continuation from the iliotibial line of the thigh) (Figs 70.3 and 70.4).

Fig. 70.3 Skin marking with the template. Markings must follow the anatomical shape of the gluteal region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree