Reconstruction of nasal defects presents a particularly unique challenge for the surgeon. Complex aesthetic subunits and limited available adjacent mobile skin with varying color, texture, and thickness all contribute to this task. The ideal reconstruction of nasal defects recruits tissue of similar color, texture, and thickness to that of the defect. Two versatile local flaps for nasal reconstruction are the glabellar flap and an extension of the glabellar flap, the dorsal nasal flap. The authors describe the use of these two local flaps for reconstruction of nasal defects and modifications of these procedures for certain indications, as well as their use in medial canthal reconstruction.

The nose occupies the central third of the face and is bordered by important functional and aesthetic structures, such as the medial canthus and lacrimal apparatus. The ideal nasal structure does not draw focus on itself but rather blends with other facial structures, focusing attention on perioral and periorbital areas. Defects of the nose and surrounding structures occur most commonly as a result of malignancy but also as a result of infection, trauma, congenital anomalies, and prior surgery. These defects, if not properly addressed, lead to a potentially aesthetically displeasing form and potentially impaired function. The surgical correction of defects of the nose and surrounding structures can pose significant challenges to the reconstructive surgeon.

Nasal reconstruction was revolutionized by Burget and Menick, who divided the nose into multiple subunits based on the multitude of differences of elasticity, color, contour, and texture of the skin. The repair of defects of the nose and surrounding structures requires the knowledge of these aesthetic subunits as well as a variety of surgical techniques. Generalized options for addressing nasal defects include primary closure, healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, and the use of local and distant flaps. Although multiple options exist, optimal results are obtained when “like is used to repair like.” The use of tissues of similar color, texture, and thickness for the repair of defects usually requires various local flaps to recruit adjacent tissue into the defect.

The purpose of this article is to revisit the application of the glabellar flap and its modifications for reconstruction of defects of the external nose. We also review modifications of these flaps to provide inner lining of the nose as well as reconstruction of the medial canthus.

Relevant anatomy

The nose is a 3-dimensional structure consisting of 3 layers. The external layer contains the skin that drapes over the middle layer, which consists of the bony/cartilaginous skeleton. The nasal cavity is lined by the third layer, which is the nasal mucosa. According to the principles of Burget and Menick, the nose can be divided into 9 aesthetic subunits. These include the paired lateral side walls; alar lobules; soft tissue triangles; and the singular nasal dorsum, nasal tip, and columella. The nasal subunits can be divided into concave and convex. The 4 concave nasal subunits include the lateral side walls and the soft tissue triangles, whereas the 5 convex subunits include the nasal tip, dorsum, columella, and paired alar lobules.

The nose may be further divided into 3 zones. Zone 1 covers the dorsum and side walls. The skin of Zone 1 is thin and does not contain sebaceous glands. Zone 2 typically begins approximately 1.0 to 1.5 cm above the supratip and covers the 3 nasal subunits consisting of the alar lobules and the nasal tip. The skin of Zone 2 is thicker than that of Zone 1 and contains sebaceous glands. Zone 3 is the most inferior skin that overlies the soft tissue triangles, columella, and infratip lobule. The skin is relatively immobile, smooth, and thin, and does not contain sebaceous glands.

The glabella is defined as the area between the eyebrows. The glabella lies directly above the nose and joins the superciliary ridges. The area is slightly elevated and contains a significant amount of redundant skin, which can be recruited for use in local flaps. The skin of the glabella is thicker relative to the skin of the nasal dorsum and this fact should be considered when designing local flaps for nasal reconstruction.

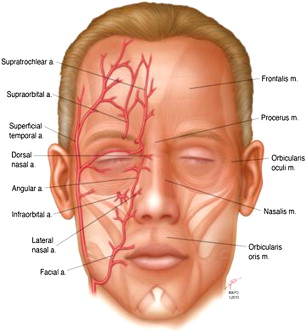

The musculature of the glabellar region consists of the frontalis, procerus, and corrugator supercilli ( Fig. 1 ). The frontalis is the anterior portion of the occipitofrontalis. The frontalis arises from the epicranial aponeurosis and inserts into the skin of the eyebrows. It functions to elevate the eyebrows and produces the transverse wrinkles in the forehead. The frontalis is innervated by the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The procerus muscles are thin extensions of the frontalis muscles arising from the skin of the eyebrows and inserting over the dorsum of the nose. Contraction of the procerus produces transverse wrinkles over the radix of the nose and is supplied by the buccal branch of the facial nerve.

The corrugator supercilli muscles arise from the medial aspect of the superciliary arch beneath the frontalis muscles. They are small thin muscles of pyramidal shape that pass between the orbital and palpebral portions of the orbicularis oculi muscles to insert on the skin of the eyebrows. Contraction of the corrugator supercilli draws the eyebrow medial and downward, producing vertical wrinkles in the glabellar region. The corrugator supercilli is innervated by the frontal branch of the facial nerve.

The vascular anatomy of the nose, and in particular that of the forehead, glabellar, and medical canthal regions, are pertinent to the design of local flaps in these regions. The blood supply to the forehead consists primarily of the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries, which branch from the ophthalmic arteries arising as the first branch of the internal carotid arteries.

An extensive vascular arcade exists around the paranasal region that communicates via multiple branches with the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries (see Fig. 1 ). The angular artery and its branches are the primary blood supply to the lateral nasal side walls and nasal dorsum. The angular artery arises from the facial artery after the latter gives rise to the superior and inferior labial arteries. The angular artery traverses the nasojugal groove giving off the lateral nasal artery, which communicates with a branch of the ophthalmic artery, the dorsal nasal artery. The extensive vasculature of this region allows axial pattern flaps to be developed in not only the glabellar, but forehead and medial canthal regions as well. For example, Kelly and colleagues performed 9 cadaver dissections and radiologic studies of the arterial anatomy of the supraorbital and paranasal region and found that the flaps based in the glabellar and medial canthal regions receive blood supply from both the angular as well as supratrochlear arteries. McCarthy and colleagues injected the facial arteries of 6 cadavers with blue dye and found blood flow to the forehead even after ligation of the supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries. These results exhibit the role of the dorsal nasal artery as a collateral circulation for the forehead with contributions from the angular artery.

Glabellar flaps in nasal reconstruction

Glabellar Flap

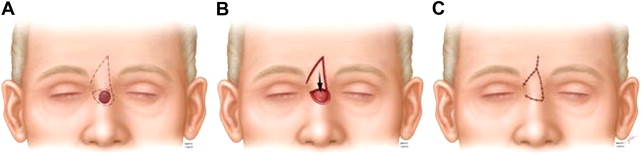

Recruitment of redundant skin from the glabella was first reported by von Graefe in 1818 with subsequent reports by Joseph, Labott, Limberg, and others. The glabellar flap has traditionally been described as a V-Y advancement flap based on a random blood supply for the reconstruction of defects of the upper third of the nose; however, multiple modifications of the procedure have been described ( Fig. 2 ). For example, Field described a modification of the V-Y advancement, which he called the glabellar transposition banner flap, in which the pedicle of the flap arises from the lateral nasal side wall on the side opposite the defect. The glabellar skin is recruited into the defect by rotation, and the secondary defect created in the glabella is closed primarily with excellent aesthetic results observed by the investigator. Field also described a bipedicled modification of the glabellar flap for reconstruction of defects of the upper third of the nose. The defect is excised and a bipedicled flap, with each pedicle originating from the lateral nasal side walls and medial canthal region, is elevated in the subcutaneous plane. The flap is advanced inferiorly and a region of glabellar skin is undermined to advance inferiorly for closure. Field reported excellent camouflage of the incisions as well as no distortion of the medial eyebrows.

Modifications of the glabellar flap have been described to address more distal defects involving reconstruction of the nasal tip, columella, alar lobule, and upper lip, generally relying on an axial blood supply rather than a random pattern. For example, Morrison and colleagues described a reverse island glabellar flap based on the terminal branches of the angular artery to reconstruct defects of the nasal tip, alar lobule, columella, and even the upper lip. The investigators observed 2 complications in their series with both consisting of superior necrosis of the flap. Most of their donor site could be closed primarily or with local flaps; however, 5 donor sites required closure with full-thickness skin grafts from a postauricular donor site. Seyhan reported a series of 10 patients undergoing reconstruction of Moh’s surgery defects of the lower eyelid, nose, and medial canthal and malar region with a modification of the reverse island glabellar flap, which he called the “radix nasi island flap” based off of the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic artery. The average defect size in greatest dimension in their series was 2 cm, and all 10 donor defects could be closed primarily.

Surgical Technique

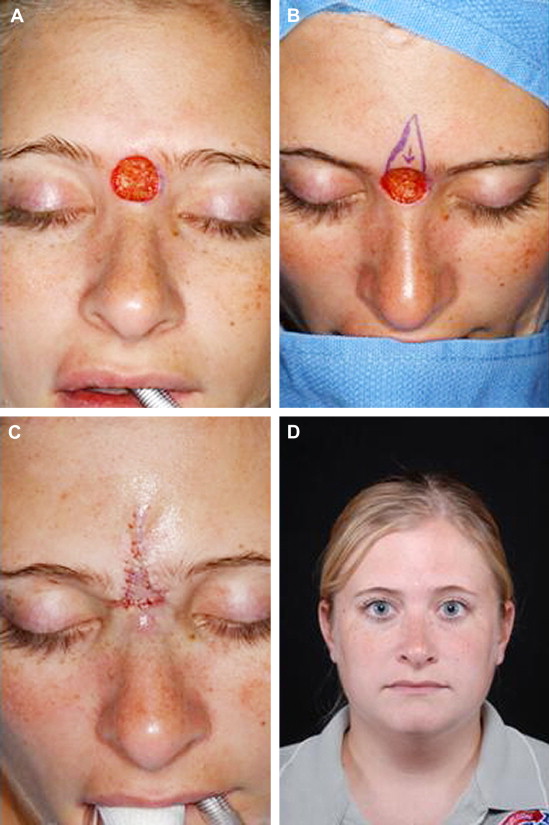

The procedure can be done under either local or general anesthesia based on patient preference, comorbidities, and other planned procedures. First, an inverted V is outlined from the midpoint of the glabella just above the brow (less than 60° angle). Both segments of the flap should extend below the brow and the longer portion of the flap should join the lateral aspect of the defect ( Fig. 3 ).

The outlined skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised with a #15 blade and undermined extensively in the subcutaneous plane. The flap is then rotated into the defect with its apex placed at the lateral edge and the point at the inferior tip of the defect. Once the tip of the flap is trimmed to fit the defect, the flap is secured with buried, interrupted, subcutaneous 6–0 Vicryl sutures. The skin is then closed with interrupted 6–0 nylon or silk sutures. The donor site is sutured in a V-Y closure, which may cause narrowing of the interbrow distance and, occasionally, require a secondary debulking procedure.

The flap may be thinned significantly at the time of harvest. Resection of most subcutaneous fatty tissues in approximately half of the distal side of the flap has been reported not to compromise the circulation to the flap. This thinning is possible because of its stable blood supply arising from the subcutaneous vascular network of the nose, consisting of the lateral nasal branch of the facial artery, the angular artery, and the dorsal nasal artery.

Advantages/Disadvantages

The glabellar flap can easily be performed under local anesthesia, leading to decreased risk to the patient and increased convenience. Additionally, glabellar flaps use local skin that is of similar texture, consistency, and color to that of the defect. The resultant secondary defect can be closed primarily in most cases, and the incisions and resultant scars are generally well camouflaged.

The disadvantages of the glabellar flap and its modifications include the thick skin of the glabella, which is frequently discrepant with the thickness of the skin of the defect; however, the glabellar flap generally tolerates thinning of the skin at the time of harvest such that this hurdle can be overcome. Although the scars are usually unnoticeable, there are reports of difficulty with pin cushioning, especially glabellar island flaps, leading to noticeable deformity and suboptimal cosmetic outcome. Finally, closure of the secondary defect can lead to narrowing of the interbrow distance, especially when larger amounts of skin are needed for reconstruction.

Glabellar flaps in nasal reconstruction

Glabellar Flap

Recruitment of redundant skin from the glabella was first reported by von Graefe in 1818 with subsequent reports by Joseph, Labott, Limberg, and others. The glabellar flap has traditionally been described as a V-Y advancement flap based on a random blood supply for the reconstruction of defects of the upper third of the nose; however, multiple modifications of the procedure have been described ( Fig. 2 ). For example, Field described a modification of the V-Y advancement, which he called the glabellar transposition banner flap, in which the pedicle of the flap arises from the lateral nasal side wall on the side opposite the defect. The glabellar skin is recruited into the defect by rotation, and the secondary defect created in the glabella is closed primarily with excellent aesthetic results observed by the investigator. Field also described a bipedicled modification of the glabellar flap for reconstruction of defects of the upper third of the nose. The defect is excised and a bipedicled flap, with each pedicle originating from the lateral nasal side walls and medial canthal region, is elevated in the subcutaneous plane. The flap is advanced inferiorly and a region of glabellar skin is undermined to advance inferiorly for closure. Field reported excellent camouflage of the incisions as well as no distortion of the medial eyebrows.