Fig. 1.1

Angiokeratomas associated with Fabry disease. Note the multiple, discrete, nonblanching, vascular papules on the penile shaft and scrotum. The differential diagnosis would also include angiokeratomas of Fordyce, which are common growths in the genital area in elderly patients and have no systemic associations. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum can occur in the setting of other lysosomal storage diseases (fucosidosis, sialidosis, etc.) and sometimes in the absence of other enzymatic abnormalities, thus is not pathognomonic for Fabry disease [8, 9]. In addition, there are other variants of angiokeratoma without the systemic associations seen in Fabry patients. These include solitary angiokeratoma, angiokeratoma of Fordyce occurring in older patients on the genitals, angiokeratoma of Mibelli seen in adolescent women on the dorsal hands and feet, and angiokeratoma circumscriptum naeviformis presenting as a unilateral plaque on the trunk or extremities with a segmental distribution [8]. Isolated, solitary angiokeratomas may be misdiagnosed as cherry angiomas, warts, pyogenic granulomas, or Spitz nevi [9]. Thus skin biopsy can be important in cementing the diagnosis.

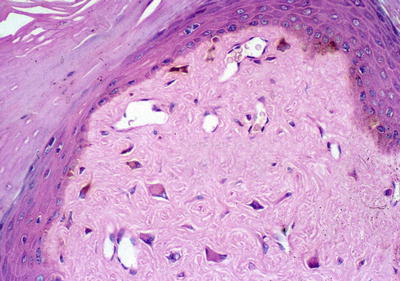

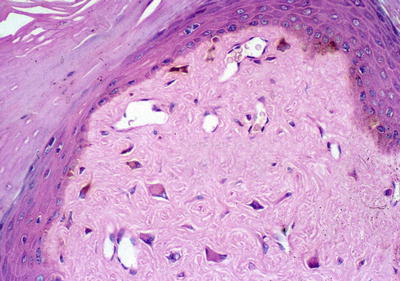

Routine histopathologic examination of an angiokeratoma fixed in formalin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin reveals a dilated, thin-walled vascular proliferation (sometimes filled with red blood cells) of the papillary dermis that is enveloped by an acanthotic epidermis with overlying hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum [3, 8]. A standard skin biopsy will not differentiate angiokeratomas associated with Fabry from angiokeratomas of other etiologies, as the endothelial lipid inclusions characteristic of Fabry disease are destroyed with tissue processing [8]. However, electron microscopic examination of an angiokeratoma in a Fabry patient will demonstrate diagnostic “zebra bodies,” which are vacuolar, electron-dense inclusions within the cytoplasm that have a lamellated appearance [3, 8].

While angiokeratomas are the most often encountered cutaneous vascular lesion in Fabry patients, telangiectasias and cherry angiomas have been reported to occur as well [11–14]. Because these lesions are quite common and can occur as multiple lesions in the general population, it is not recommended that patients presenting with these be screened for Fabry disease. However, if there is a family history of Fabry disease or personal history of other associated Fabry symptoms, further evaluation may be indicated [11, 12].

Other skin manifestations can include abnormalities of sweating, lymphedema, and characteristic facies. Hypohidrosis is reported by patients more commonly than anhidrosis or hyperhidrosis, but all have been documented to occur [3]. This is likely due to GL-3 accumulation in sweat glands [1]. In addition, the same lipid deposition that occurs in vascular endothelium has been proposed to occur in lymphatic vessels, which is thought to contribute to the development of lymphedema, seen in up to 25 % of men with Fabry disease [3, 15]. Fabry facies are seen more often in affected males, but the features can be seen to a lesser degree in females. These features include “recessed forehead, bushy eyebrows, prominent supraorbital ridges, widened nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, shallow midface, full lips, coarse features, posteriorly rotated ears, and prognathism” [8].

Renal Manifestations

Fabry nephropathy is caused by glomerular and renal vascular deposition of neutral glycosphingolipids, which have been demonstrated as early as in utero [16]. Thus timely diagnosis and treatment is crucial in preventing progressive decline in renal function, which can culminate in need for dialysis or kidney transplantation [4]. In fact, it is recommended that those with chronic kidney disease (men younger than age 50, women of any age) of unknown etiology be screened for Fabry disease [17], as this diagnosis may be causative in up to 0.2 % of all dialysis patients [4]. In patients with known Fabry disease, serial monitoring for albuminuria and decline in glomerular filtration rate should begin in adolescence [17]. Studies have demonstrated that enzyme replacement therapy does not appear to be effective at halting disease progression in patients with proteinuria >1 g/day or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [17]. Therefore, initiation of enzyme replacement therapy is most beneficial in those who have not yet reached these thresholds. Chronic kidney disease stage 5 usually develops on average in patients after age 30 years, but it has been reported in a patient as young as age 16 years [17].

In patients with rapidly declining renal function, renal ultrasound should be performed to rule out other possible causes, such as renal cysts [4].

Renal biopsy can be undertaken in those with known Fabry disease and in whom it is unclear whether enzyme replacement therapy should be started. If electron microscopic examination reveals GL-3 within podocytes and vascular endothelial cells, enzyme replacement therapy may be indicated [4].

A less invasive test to assess for Fabry disease of the kidney is urine microscopy. When viewing urine sediment via polarized microscope, autofluorescent, birefringent Maltese cross lipid particles can be seen. Different morphologies of Maltese cross particles have been defined, with those having a lamellated appearance with surface protrusions being most sensitive and specific for Fabry disease [18].

Cardiovascular Manifestations

Glycosphingolipids also accumulate in various cardiac tissues, leading to dysfunction. Myocytes, valves, conduction tissue, and vascular endothelium may all be affected, and the resulting presenting symptoms include dyspnea, syncope, palpitations, or angina [19]. Over time, patients can go on to develop left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, dysrhythmia, ischemia, and/or valvular insufficiency [19, 20].

The cardiomyopathy of Fabry disease is classified as restrictive, due to infiltration of glycosphingolipids within the cardiac myocytes [19]. However, Fabry disease represents an unusual subset of restrictive cardiomyopathy, as there is often lack of significant left ventricular filling defects with presence of left ventricular hypertrophy (with patients meeting high voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy via electrocardiogram) [21]. It was initially hypothesized that the enlargement of the ventricle was simply due to the volume of lipid deposition within the lysosomes, but it was later shown that this only accounted for 1 % of the increased left ventricular mass [21]. It is now thought that there is an increase in left ventricular muscle mass that accounts for the hypertrophy, although the etiology of this is unclear [21]. The presence of left ventricular hypertrophy can be demonstrated via echocardiography, electrocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [21].

Dysrhythmias occur as a result of glycosphingolipid deposition within the conduction system or by atrial dilatation and ischemia due to left ventricular hypertrophy [19, 21]. While atrial fibrillation is most commonly reported, supraventricular tachycardia, various degrees of heart block, premature ventricular beats, and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia have also been shown to occur [19, 21].

Over half of Fabry patients complain of anginal chest pain, with glycosphingolipid deposition within cardiac endothelial cells playing a role in vascular dysfunction and ultimately in myocardial injury [21]. However, the exact mechanism is unclear. Vasospasm or perhaps decreased coronary perfusion due to left ventricular hypertrophy may be causative [21]. Atherosclerotic plaques causing stenosis do occur in Fabry patients, but cardiac catheterization has not been performed routinely and thus the true incidence of this is unclear [21].

Valvular insufficiency most often manifests as mitral valve regurgitation, but patients do not generally require valve replacement [19].

Neurologic Manifestations

The peripheral, central, and autonomic nervous systems may all be affected in Fabry disease.

Fabry pain crises, occurring as attacks of neuropathic pain, may be the first manifestation of the condition. They can begin in early childhood with episodes of severe, burning pain in the distal extremities, brought on by stress, infections, or changes in temperature and lasting minutes to days [4, 22]. Deposition of GL-3 within the small vessels of the peripheral nerves leads to vascular spasm and infarction that culminates in a small-fiber peripheral neuropathy [22]. Quantitative sensory testing can be done to evaluate this and often demonstrates abnormalities in thermal sensation [23]. Punch biopsy of the skin stained for nerve fibers can also reveal a decrease in density of these fibers [24]. Involvement of large fibers (indicated by loss of vibration and pinprick sensation) generally occurs only in those with renal disease [4, 23].

Cerebrovascular disease, caused by glycosphingolipid deposition within cerebral vessels, is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with Fabry disease [4, 25]. Transient ischemic attacks and ischemic strokes (preferentially affecting the vertebrobasilar territory) can occur in both men and women and often at a young age [4, 7, 25]. Half of male patients experience their first stroke before the diagnosis of Fabry disease is rendered, and it has been estimated that up to 5 % of males and 2.5 % of females with stroke of unknown cause may carry a diagnosis of Fabry disease [3, 4]. In addition to vascular disease, patients may also demonstrate white matter lesions and cortical atrophy with magnetic resonance imaging [4, 25].

Involvement of the autonomic nervous system manifests as abnormalities of sweating and gastrointestinal complaints [4].

Ophthalmologic Manifestations

Cornea verticillata, bilateral, whorl-shaped corneal opacities diagnosed by slit-lamp examination, is the characteristic eye finding in patients with Fabry disease and can be seen in nearly all patients by age 10 [25]. This clinical finding is caused by deposition of GL-3 in the limbal blood vessels of the epithelial basement membrane and does not affect vision [25]. On examination, there are yellowish lines emanating outward from the central cornea in pattern resembling a vortex. Medications and other lipid storage diseases can also cause cornea verticillata, but in Fabry disease, the deposits are lighter colored and more superficial [4, 25]. Lens opacities and tortuosity of the conjunctival vessels have also been described [25].

Other Organ Involvement

Other symptoms reported in Fabry patients are diverse and can include:

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis of Fabry disease are as follows: attacks of pain in distal extremities triggered by physiological or psychological stress, cutaneous angiokeratomas, proteinuria or renal failure of unknown cause, left ventricular hypertrophy, stroke, characteristic corneal opacities, and unexplained gastrointestinal complaints [7, 22].

In affected males, the diagnosis can be confirmed by measuring alpha-galactosidase A activity in plasma or peripheral leukocytes [6, 22]. Males with classic Fabry disease will have less than 1 % enzyme activity, while those with atypical forms may have higher levels of enzyme activity [22]. Some experts then suggest that GLA gene sequencing analysis be performed subsequently to identify the specific causative mutation [17]. Most families with Fabry disease have family-specific mutations, and over 300 of these have been described [6].

Female carriers have variable levels of alpha-galactosidase activity (may be normal or very low), so this test is not reliable in diagnosing women. Suspected female carriers must undergo molecular testing to confirm the diagnosis [6, 17, 22].

Other diagnostic tests can include detection of accumulating glycosphingolipids. Urinary GL-3 levels and plasma deacetylated GL-3 levels may be elevated in affected patients. In addition, analysis of urinary sediment via polarized microscopy may reveal Maltese crosses [17].

Disease Course and Prognosis

Fabry disease is chronic and slowly progressive, with premature death resulting from renal failure, heart disease, or stroke. This generally occurs at around age 50 for classically affected males, whose life span is reduced by 20–25 years compared to the general population [25]. Carrier females also experience a reduced life expectancy, with average age of death at around 70 years [3, 25].

Monitoring

The clinical effects of GL-3 accumulation are far-reaching; thus multiple disciplines are likely to be involved in the care of a patient with Fabry disease. Once a diagnosis has been established, patients should undergo complete history (including family history) and physical examination. Patients should be asked about pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, and these should be documented for longitudinal follow-up. Examination for cutaneous vascular lesions (which may occur underneath undergarments) should be done [6, 26]. Recommended laboratory evaluation can include hematology, chemistries, urinalysis, and 24 h urine collection for protein [6]. In addition, obtaining a baseline echocardiogram and electrocardiogram is advised [4, 26]. To assess for white matter lesions, a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging study may be indicated [4]. Consider referral to ophthalmology for slit-lamp examination and referral for audiologic testing as well [7].

Follow-up should occur at least annually, with many of the above tests being repeated each year [6]. However, some have recommended more frequent monitoring [17]. It is important to keep in mind that end-organ damage may occur in the absence of clinical symptoms, and the studies mentioned may help identify an early need to intervene with therapy.

Treatment

Prior to the advent of enzyme replacement therapy, treatment for Fabry disease focused primarily on supportive and symptomatic care based on the patient’s complaints [6, 27]. These adjunctive therapies are still important in managing patients with Fabry disease. Pain should be controlled, although narcotics should be avoided and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are generally ineffective [6]. Monitoring for and treatment of cardiac comorbidities such as hypertension, dysrhythmias, and hyperlipidemia should be undertaken. Providers should also consider use of antiplatelet therapy, particularly in patients with transient ischemic attacks or stroke [4, 6]. In patients with proteinuria, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is recommended [4, 6]. In advanced renal disease, dialysis or kidney transplantation can prolong life [6]. Given the large number of lesions, angiokeratomas are treated only when symptomatic. Different treatment modalities reported to be effective include excision, cryosurgery, and laser therapy [1].

Enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease in the form of recombinant alpha-galactosidase A is available in two forms. Agalsidase-alpha is produced from human fibroblasts, while agalsidase-beta is produced from Chinese hamster ovarian cells [22]. Only the latter is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use in the United States, although both forms have been approved for use outside of the United States [7]. Agalsidase-alpha is administered via intravenous infusion every 2 weeks at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg. Agalsidase-beta is also administered via intravenous infusion every 2 weeks, but the dose is higher at 1.0 mg/kg [26]. Average annual cost of enzyme replacement therapy for an adult was estimated at $250,000 in 2007 [7].

Patients generally tolerate enzyme replacement therapy well, with only a small minority of patients experiencing infusion reactions. These adverse reactions can usually be managed by premedicating patients with antihistamines or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Sometimes, decreasing the infusion rate is helpful. For more severe reactions, systemic corticosteroids may be needed. The reactions tend to be less severe over time [6].

Enzyme replacement therapy has been shown to decrease plasma and renal capillary endothelial levels of GL-3, with studies showing stabilization of renal function. However, some have suggested that those with advanced end-stage renal disease may not demonstrate these benefits [7]. Enzyme replacement therapy has also been demonstrated to clear glycosphingolipids from cardiac tissue, thus improving left ventricular hypertrophy and overall cardiac function [4]. Of note, cardiac disease has been reported to occur in patients actively on enzyme replacement therapy, and the effect of enzyme replacement therapy on survival has not been proven [22]. Studies have also not been able to show clearly that enzyme replacement therapy has a positive impact on cerebrovascular complications of Fabry disease [7]. Enzyme replacement therapy has been shown to improve neuropathic pain and autonomic dysfunction, but patients may require additional pain management depending on their symptoms [4, 7]. Enzyme replacement therapy has also been demonstrated to improve quality of life, improve peripheral nerve function, improve hearing and vestibular function, and relieve gastrointestinal complaints.

It is recommended that enzyme replacement therapy commence as soon as possible after a diagnosis of Fabry disease is rendered. Symptomatic carriers should also be strongly considered for enzyme replacement therapy [22].

Genetic Counseling

Fabry disease is inherited in an X-linked recessive fashion. An affected father will not pass on the mutation to his sons, as they inherit his Y chromosome, which does not contain the mutation. An affected father will pass on his faulty X chromosome to his daughters, making them carriers of Fabry disease. In the offspring of a carrier mother (who has one normal X chromosome and one affected X chromosome), 50 % of females will inherit the mutation (making them carriers as well) and 50 % of males will inherit the mutation (giving them Fabry disease) [25]. Specific recommendations for testing are shown under the diagnosis heading.

Tuberous Sclerosis

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by inactivating mutations of either of the tumor suppressor genes, TSC-1 or TSC-2, encoding for hamartin and tuberin respectively [28]. Downstream effects include activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway with subsequent disordered cellular proliferation and differentiation, producing hamartomatous lesions in multiple organ systems including brain, skin, lungs, kidneys, heart, retina, and liver [28, 29]. The triad of seizures, mental retardation, and facial angiofibromas described by Vogt in 1908 are only present in about 30 % of patients. As reflected in this diagnostic triad, neurological and dermatological findings are the most common disease manifestations experienced by tuberous sclerosis patients, occurring in up to 90 % [28, 30]. Neurologic manifestations, namely seizures, are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with tuberous sclerosis [29]. Causes of death in affected patients vary by age, with status epilepticus and brain tumors being most common in younger patients and renal failure predominating in older patients [31]. Thus, early recognition and intervention is crucial, with both medical and surgical management playing a role. In the past several years, pharmacotherapy for tuberous sclerosis in the form of mTOR inhibitors has shown promise at causing regression of the hamartomatous lesions [32].

Epidemiology

The disease affects all ethnicities and both genders [31], and the incidence has been estimated at 1 in 6,000 live births [28]. Population-based studies have estimated an overall prevalence of 1 in 14,000 to 1 in 25,000. As most patients are diagnosed before age 15 months, prevalence decreases with age [33]. Of note, these numbers may represent underestimates of the prevalence because they do not account for undiagnosed cases in patients who have only mild disease or are asymptomatic [29].

Genetics

Tuberous sclerosis results from inactivating mutations in either the TSC-1 or TSC-2 tumor suppressor genes encoding for proteins hamartin and tuberin respectively. Although tuberous sclerosis is autosomal dominantly inherited, up to 2/3 of patients have sporadic mutations [30]. Mutations in TSC-1 are more commonly reported (15–30 % of affected families) whereas mutations in TSC-2 are slightly less common (10–20 % of affected families) [30]. Over 1,200 allelic variants have been discovered in both the TSC-1 and TSC-2 genes, accounting for the widely varying phenotypes [29]. However, it is important to note that even family members with the same genetic mutation may have differing degrees of clinical manifestations. While attempts to correlate genotype and phenotype have not been consistent, studies have demonstrated that patients with the TSC-2 mutation have more severe disease [30].

The molecular pathway affected by tuberous sclerosis gene mutations has been elucidated. In unaffected patients, hamartin and tuberin form an intracellular heterodimer that, through cell signaling pathways, ultimately inhibits the protein kinase mTOR, a regulator of cellular proliferation, differentiation, and growth [28, 29]. In patients with TSC mutations, there is constitutive activation of mTOR leading to abnormalities in cell cycle progression, cellular metabolism, gene transcription, and protein translation [28, 33]. The resulting effect is the overgrowth of widespread benign tumors called hamartomas in multiple organ systems.

Mucocutaneous Findings

Characteristic skin findings comprise a number of the diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis, so a complete cutaneous examination is important in establishing the diagnosis. Clinicians should be aware that patients present with differing skin manifestations based on their age, so serial follow-up over time is also essential.

The earliest skin finding in tuberous sclerosis patients is the ash leaf spot, an ovoid, hypopigmented macule or patch measuring 1.0–12 cm in diameter [29] (see Fig. 1.2). Ash leaf spots are one of the most common cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis, occurring in over 90 % of patients [29]. Some have described the shape of the lesion as having a sharper tip at one pole and a rounded tip at the other, while others have likened it to a thumbprint shape [29]. The lesions are generally present at birth, although they may be difficult to appreciate without the use of a Wood lamp that accentuates the pigment change. The ash leaf spots become more apparent with age and are usually obvious by age 2 [34]. At least three hypomelanotic macules must be present as part of the major diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35]. Hypomelanotic lesions are common in the general population, with 5 % having one lesion, 1 % having two lesions, and 0.1 % having three lesions [29]. The differential diagnosis for ash leaf spots includes vitiligo, which is classically depigmented rather than hypopigmented; nevus depigmentosus, which occurs in the absence of other systemic findings; and nevus anemicus, a vascular anomaly wherein a localized hyperreactivity to catecholamines causes vasoconstriction that can be confused for hypopigmentation.

Fig. 1.2

Ash leaf macules associated with tuberous sclerosis. These hypopigmented macules and patches are often the first cutaneous manifestation of tuberous sclerosis. There are also confetti-like macules on the lower trunk. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

Confetti-like hypopigmented macules also occur in patients with tuberous sclerosis, with the onset being later in life [29]. They have been reported less commonly than ash leaf spots, with studies reporting presence in 3–30 % of patients [29]. These lesions are smaller than ash leaf spots, occur symmetrically over extremities, and are numerous [29]. They are one of the minor diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35]. The confetti-like hypopigmentation may clinically mimic idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, a benign dermatosis which is seen in middle-aged patients and has no associated systemic features [29].

Facial angiofibromas (previously labeled inaccurately as adenoma sebaceum) were a part of the initial diagnostic triad described by Vogt and remain a part of the major diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35]. They typically appear in childhood but not before age 3 [36]. They become more prominent with puberty and can be mistaken for acne vulgaris. However, acne lesions also include comedones and pustules, which are not associated with tuberous sclerosis. Angiofibromas are skin colored to erythematous smooth papules that measure a few millimeters in diameter and occur in multiple over the central face, particularly within the nasolabial folds and sparing the central upper cutaneous lip [29]. They may be found in over 70 % of patients with tuberous sclerosis [34] (see Fig. 1.3). As the name suggests, histopathology demonstrates a fibrotic dermis containing large and stellate fibroblasts with prominent, dilated capillaries [29] (see Fig. 1.4). Facial angiofibromas are not pathognomonic for tuberous sclerosis and can be seen as an isolated finding in the general population [35]. In addition, most patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I will also have facial angiofibromas. Multiple facial angiofibromas can also resemble the facial adnexal neoplasms seen in other genodermatoses, such as the tricholemmomas of Cowden disease, the fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas of Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) disease, and the cylindromas of Brooke-Spiegler disease. These lesions can be differentiated by their histopathology.

Fig. 1.3

Angiofibromas associated with tuberous sclerosis. The multiple, smooth, pink papules of the mental crease are characteristic of the condition. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

Fig. 1.4

Angiofibroma histopathology. There are stellate fibroblasts within the fibrotic dermis, which also demonstrates increased vasculature. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

A forehead plaque, which is a type of angiofibroma, is present in roughly 20 % of tuberous sclerosis patients and appears in childhood, enlarging over time [34]. They are indurated, elevated plaques measuring a few centimeters in diameter that are skin colored to slightly yellow in color. It shares histologic features with facial angiofibromas [29].

Shagreen patches are connective tissue hamartomas that appear in over 30 % of young children with tuberous sclerosis [34]. The lumbosacral area is the most common site of involvement for these benign tumors, which are described as skin colored to slightly brown in color, irregularly shaped raised plaques with ill-defined borders and a cobblestoned surface [34] (see Fig. 1.5). The shagreen patch comprises one of the major diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35]. Biopsy of this connective tissue nevus often shows dense bands of collagen with accompanying increases in connective tissue elements such as vasculature, elastic tissue, adipose tissue, and smooth muscle [29].

Fig. 1.5

Shagreen patch associated with tuberous sclerosis. This ill-defined, subtle, skin colored to pink plaque on the trunk has a slightly cobblestoned surface. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

Fibromas of the nail unit, also known as Koenen tumors, tend to occur in adolescents and young adults with tuberous sclerosis and have been reported in nearly 70 % of affected patients [29]. These lesions are skin-colored, smooth papules and nodules that are found in association with both fingernails and toenails and are localized to the lateral or proximal nail fold in most cases [29] (see Fig. 1.6). Ungual fibromas can also occur as a result of trauma, but when seen in the absence of preceding trauma, these lesions are part of the major diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35]. Biopsy of one of these lesions shows histologic features similar to those of the facial angiofibroma [29].

Fig. 1.6

Ungual fibromas associated with tuberous sclerosis. This patient has multiple skin colored to pink smooth nodules surrounding the nail plate with associated nail dystrophy. Photo courtesy of Dirk Elston, M.D.

Other skin findings reported in tuberous sclerosis patients include café au lait macules (well-marginated, evenly pigmented, tan-brown macules) and molluscum fibrosum pendulum (fleshy, pedunculated papules resembling skin tags), which are quite common in the general population. Their significance in tuberous sclerosis is unclear, and these clinical findings are not included in the diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [29].

Oral examination is important in patients with suspected tuberous sclerosis, as dental enamel pitting and gingival fibromas comprise two of the minor diagnostic criteria for the condition [35]. Dental enamel pitting has been described in 50–100 % of patients with tuberous sclerosis, usually apparent at the labial surfaces of the canine and incisor teeth [29]. Gingival fibromas are most often seen on the anterior segment of the upper jaw but have been described elsewhere in the mucosa [29].

Renal Manifestations

Just as hamartomas form in the skin as a result of hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway, renal hamartomas also occur in patients with tuberous sclerosis.

The most commonly encountered renal tumor is the benign angiomyolipoma, which is seen in up to 80 % of patients with tuberous sclerosis [32]. Lesions are often multiple and bilateral and are seen up to four times more often in female patients [34]. Renal involvement begins in infancy, with size and number of lesions increasing with age [34]. Lesions are usually asymptomatic, but they may cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and palpable masses [31]. As the name suggests, angiomyolipomas are tumors composed of abnormal vasculature, smooth muscle, and fatty tissue [30]. While they are considered benign, the most serious and common complication is spontaneous hemorrhage of the abnormal vessels (often aneurysms) contained within [32]. The risk of hemorrhage in tuberous sclerosis patients is estimated at 25–50 % (with up to 20 % of these patients presenting with hypovolemic shock), with lesions greater than 5 cm in diameter having the highest risk [28]. Surgical resection is discouraged in order to preserve renal function, and lesions are preferably treated with embolization [32]. With growth, these lesions may also encroach upon normal renal tissue, leading to dysfunction and potentially to renal failure [28]. It is important to note that these lesions can occur independently of tuberous sclerosis, as only 20 % of patients with angiomyolipomas have tuberous sclerosis [31]. However, angiomyolipomas do comprise one of the major diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35].

Renal cysts are the second most common kidney manifestation of tuberous sclerosis, occurring in about 50 % of patients [28]. These lesions are generally asymptomatic but can lead to development of hypertension [28]. When symptomatic, lesions are usually larger than 4 cm in diameter and can cause flank pain and hematuria [34]. In 2–3 % of patients with tuberous sclerosis, their gene mutation may involve contiguous deletions in TSC-2 and the adjacent gene for polycystic kidney disease, PKD-1 [30]. These patients develop multiple, large cysts with onset of renal failure in early adulthood [30]. The presence of multiple renal cysts is one of the minor diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis [35].

Renal cell carcinoma has also been reported in patients with tuberous sclerosis, but notably the overall incidence of 2–3 % is similar to that of the general population [32]. Patients with tuberous sclerosis tend to develop malignancy at an earlier age, with some studies showing an average age at diagnosis of 28 years (25 years younger than in the general population) [28]. Varied subtypes of renal cell carcinoma have been demonstrated, including clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe [31]. Benign oncocytomas have also been reported [37]. It is important to note that the true incidence of renal cell carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis may be incorrect because some cases of angiomyolipomas (particularly the epithelioid variant) may be misdiagnosed as renal cell carcinoma [37]. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in making this distinction.

Neurologic Manifestations

As noted by Vogt in his descriptive triad of tuberous sclerosis, two of the three findings (seizures and mental retardation) result from neurologic involvement of characteristic hamartomatous lesions. However, the degree to which patients manifest these two findings is highly variable, with some having no seizures and normal intellect and others having severe, intractable seizures with profound mental retardation [34]. It has also been recognized that patients with tuberous sclerosis have impairments in cognition and behavior, with 25 % carrying a diagnosis of autism [37]. The four common central nervous system manifestations include cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, and white matter abnormalities [31], with the first three lesions each accounting for major diagnostic criteria and the last accounting for a minor diagnostic criterion for tuberous sclerosis [35].

Cortical tubers are the hallmark lesion of tuberous sclerosis [37] and are thought to be responsible for causing many of the neurologic symptoms in affected patients [31]. Tubers are histologically comprised of disorganization of the six-layered structure of the cerebral cortex with proliferation of both glial and neuronal cells [30, 38]. They have been identified in patients as young as 20 weeks gestational age [32], and they are usually diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging [38]. Cortical tubers vary in size, number, and anatomic location, and these factors likely account for the variation in clinical manifestations [38]. Foci of seizure activity map to areas where tubers are present [38], and patients with numerous (>7) tubers tend to have seizures that are more difficult to control [32]. Improvement in seizure activity with resection of the tubers has been well documented [38]. Tubers in the frontal and parietotemporal regions have been associated with autism [31]. These lesions remain present throughout life, although malignant transformation has not been reported [38].

Subependymal nodules are benign hamartomas that grow on the surface of the cerebral ventricles [38]. They are present in utero and may enlarge or calcify over time, but in most patients they are asymptomatic [30]. Subependymal nodules that are larger than 5 mm and are located near the foramen of Munro are at risk for transforming into subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (which also have benign biological features [31]), and this process occurs slowly over time [30]. The tumors pose a risk when they enlarge to sufficient size to impede the flow of cerebrospinal fluid through the foramen of Munro, leading to increased intracranial pressure [30, 38].

White matter abnormalities include radial white matter bands (this particular finding is considered a minor diagnostic criterion for tuberous sclerosis), cyst-like white matter lesions, and superficial white matter abnormalities seen with cortical tubers [31]. These can be diagnosed radiologically [31].

The most common neurological symptom in affected patients is epilepsy, which has been reported in up to 90 % of patients [38]. In addition, seizures are the leading cause of morbidity and poor quality of life in patients with tuberous sclerosis [34, 37]. The types of seizures reported include complex partial, generalized tonic-clonic, myoclonic, and infantile spasms [38]. Over time, the epilepsy progressively worsens and becomes more resistant to medical therapy; developmental delay is strongly associated with poor control of seizure activity [38]. Therefore, aggressive control of seizures either medically or surgically is recommended [37]. Specific therapies are discussed later. A majority of patients have their first epileptic event in the first 2 years of life [29], presenting with either infantile spasms or partial seizures that may progress to generalized seizures [37].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree