Functional Anatomy and Principles of Uper Extremity Surgery

Kate W. Nellans

Kevin C. Chung

INTRODUCTION

This chapter presents the common elements in the evaluation and conduct of hand surgery.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

Hand and Digits

The thumb is a unique and specialized digit with tremendous mobility and strength, essential for power and precision grips. Painful arthritis at the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint can be crippling, and laxity at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb can prevent a strong oppositional grip because of joint instability. The mobility of the CMC joints of the index through small fingers increases toward the ulnar aspect of the hand. Angulated fractures are generally better tolerated, therefore, in the ulnar digits because of compensatory motion.

The MCP joints of the index through the little fingers have little tolerance for stiffness because the arc of motion for the fingers starts at the MCP joints. Motion at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints also contributes to making a fist, but stiffness is better tolerated in these joints, particularly the DIP joints because stability, rather than mobility, is more important in the terminal joints. Rotational or angular deformities are not tolerated because they may lead to scissoring of the fingers by interfering with the motion of the adjacent normal finger, or catching on pockets and clothing.

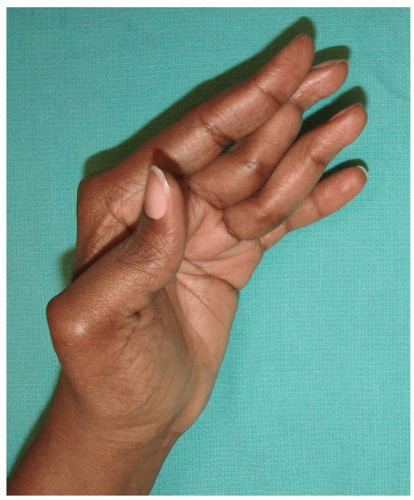

The forces acting across these joints include both static constraints (collateral ligaments, joint capsules, and volar plates) and tendons that create dynamic compression through movements. The volar plate of the MCP, PIP, and DIP may be involved in dislocations, both prior to and following reduction (Chapter 81). For dorsal MCP dislocations, if the deformity is accentuated in an attempted reduction, the volar plate may have become interposed in the joint, necessitating open reduction in the operating room. If the volar plate is disrupted during dorsal dislocation of the PIP joint, the lateral bands may subluxate dorsally over time, causing hyperextension at the PIP and flexion at the DIP, known as a “swan-neck” deformity (Figure 70.1). Another common finger deformity is the boutonniere deformity. This occurs when the insertion of the central slip on the dorsal middle phalanx and the triangular ligament are disrupted, causing the lateral bands to subluxate volarly. The PIP joint becomes flexed, and the DIP hyperextends (Figure 70.2).

Most flexion and extension of the fingers and wrist results from forearm-based muscle groups, innervated far proximally. Finely controlled movements, however, use the intrinsic musculature of the hand (muscles that arise in the hand), which includes the thenar and hypothenar muscle groups, the adductor pollicis, lumbrical, and interosseous muscles. More distal nerve lacerations or compressive pathologies affect these intrinsic muscles without deficits in the other flexors and extensors (Chapters 74 and 77).

Wrist

The wrist consists of eight carpal bones grouped in two rows with restricted motion between them and is the most complex joint in the body. The term “wrist” is used to include any of these numerous articulations. Normal flexion/extension motion is 90°/70°, but an 80° arc provides good function.1 Reduction in hand pronation is well tolerated if one has a functional shoulder to compensate, whereas loss of supination is not as easily tolerated.

The distal radioulnar joint is unique in that the ulna makes no direct contact to the carpal bones and is connected to the radius through the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). Eighty percent of the forces through the arm are dispersed by the carpal articulation with the radius. Static restraints to the movements at the radiocarpal joint include the tough, strong volar capsular ligaments, as well as less stout dorsal capsular ligaments. Incising the volar capsular ligaments to assess articular congruity when performing an ORIF (open reduction and internal fixation) of a distal radius fracture is discouraged, because this can lead to instability.

Movements between the carpal rows are biomechanically complex. The lunate is an intercalated segment sandwiched between the scaphoid and the triquetrum which follows the bone to which it is still attached. Dorsal tilt occurs when the scapholunate ligament is torn because the scaphoid flexes and the lunate must extend with the triquetrum (resulting in a dorsal intercalated segment instability) (Figure 70.3). A more rare condition occurs when the lunotriquetral ligament is disrupted, leaving the scapholunate ligament is intact, resulting in flexion of the lunate with the scaphoid (resulting in a volar intercalated segment instability) (Chapter 81).

Wrist and finger motions are the result of combined actions and firing of multiple muscle groups. For example, wrist flexion requires a balanced flexion of both the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor carpi radialis to prevent deviation in one direction or the other. The finger flexors and the median nerve run through the carpal tunnel, which is covered by the transverse carpal ligament connecting the hamate and the pisiform ulnarly to the scaphoid and trapezium radially (Chapter 77). The median nerve is susceptible to compression in carpal tunnel syndrome and when dorsally displaced distal radius fractures increase the pressure at the carpal tunnel. The extensors

of the wrist and hand are grouped into six tightly bound fibroosseous compartments (Chapter 78). Stenosis or tenosynovitis can develop due to the restricted spaces and movements, commonly resulting in De Quervain syndrome at the first dorsal compartment, or intersection syndrome at the crossover of the first on the second compartment tendons (Chapter 79).

of the wrist and hand are grouped into six tightly bound fibroosseous compartments (Chapter 78). Stenosis or tenosynovitis can develop due to the restricted spaces and movements, commonly resulting in De Quervain syndrome at the first dorsal compartment, or intersection syndrome at the crossover of the first on the second compartment tendons (Chapter 79).

PRINCIPLES OF UPPER EXTREMITY SURGERY

Acute Injuries

Emergency room management of patients with hand injuries includes an assessment of other, life-threatening injuries. One should always remember the expression “life over limb.” A severely mangled hand may attract attention, but the patient must be assessed in sequence to verify that all life-threatening conditions are treated first. Attempting to “tie off” a bleeding vessel in the emergency room is not recommended, because hemorrhage can usually be controlled with elevation and direct pressure. A blood pressure cuff may be inflated above the systolic blood pressure to control bleeding, but should not be left in place for longer than necessary, 90 minutes at most, to prevent ischemic reperfusion injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree