FROSTBITE

I. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A. Heat loss can occur via four distinct mechanisms

1. Evaporation: Direct absorption of body heat by water (sweat)

2. Conduction: Direct loss of heat via contact with colder object

3. Convection: Heat loss via movement of current/airflow

4. Radiation: Direct loss of body heat to air

B. Patients at highest risk for frostbite have decreased awareness of cold, loss of instinct to seek shelter, loss of shivering reflex, and/or cutaneous vasodilation. An easy way to remember these risk factors is the “I’s” of frostbite. (from Mohr, 2009).

1. Intoxicated (alcohol or other drugs)

2. Incompetent (patients with mental illness or dementia)

3. Infirm (elderly patients ± falls)

4. Insensate (extremity neuropathy)

5. Inducted (increased risk in wartime)

6. Inexperienced (those new to cold climates)

7. Indigent (homeless)

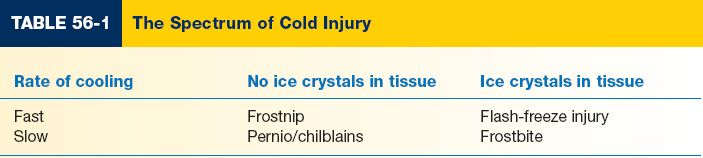

II. SPECTRUM OF COLD INJURY (Table 56-1)

A. The spectrum of cold injury relates to

1. How rapidly the body part is cooled

2. Presence or absence of ice crystals in the tissue

3. Rapid freezing causes intracellular ice crystallization, leading to architectural damage and cell death

4. Slow freezing causes extracellular ice crystallization, leading to intracellular dehydration from osmotic fluid shift out of cells

5. Frostnip is a mild, reversible cold injury with skin pallor, pain, and local numbness

6. Pernio or chilblains is a more severe cold injury from repeat exposures to near-freezing temperatures. This presents as violaceous nodules and plaques with local pain and prurutis on repeat cold exposure.

7. Flash-freezing occurs when tissue is rapidly cooled, resulting in ice crystal formation. An example of this would be licking a metal pole in winter.

III. FROSTBITE—PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND STAGING

A. Frostbite occurs in response to slow rate of cooling with ice crystal formation in tissue

B. Ice crystal formation occurs when tissue temperature reaches 28° F.

______________

*Denotes common in-service examination topics

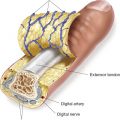

C. Concentrated solutes draw fluid out of cells and ice crystals subsequently cause cell membrane puncture.

D. Intravascular ice crystals cause direct vascular damage and indirect vascular sludging.

E. With rewarming, tissue thaws from blood vessels outward.

F. Freeze-induced endothelial damage allows capillary leak that allows extravasation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mast cells. This results in inflammation, edema, and microvascular stasis and occlusion.

G. Blisters will form at 6 to 24 hours when extravasated fluid collects beneath detached epidermal sheet. If dermal vascular plexus is disrupted, hemorrhagic blisters will be present.

H. Stages of frostbite

1. First degree: Hyperemia, intact sensation, no blisters on rewarming, no tissue loss expected

2. Second degree with blisters containing clear or milky fluid, local edema, no tissue loss expected

3. Third degree with hemorrhagic blisters, edematous tissue, shooting or throbbing pain, and likely tissue loss

4. Fourth degree with mottled or cyanotic skin, hemorrhagic blisters, and frozen deeper structures. Mummification occurs over several weeks.

IV. FROSTBITE—TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

A. Do not rewarm if any chance of refreezing exists.

B. Multiple freeze-thaw cycles causes multiplicative, not additive, damage to the affected tissues.

C. Intact blisters should be left alone. Debride ruptured blisters and apply bacitracin ointment or silvadene.

D. Beware of the afterdrop phenomenon during rewarming

1. Afterdrop occurs when central rewarming results in peripheral vasodilation.

2. This returns cold blood from the extremities to central circulation and can result in systemic hypothermia.

V. *INITIAL FROSTBITE TREATMENT

A. Rapid rewarming of affected area in 104 to 108°F water bath, not radiant heat.

B. Ibuprofen 400 mg PO q12 hours

C. Penicillin 600 mg q6 × 48 to 72 hours.

D. Elevation of limb with splinting to decrease movement

E. No smoking, caffeine, or chocolate

F. Tetanus prophylaxis

G. Three-phase bone scan may identify “at-risk” tissue

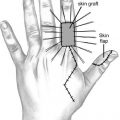

VI. ACUTE INTERVENTIONS

A. For stable patients with severe frostbite, rapid extrication to a center with interventional radiology capabilities within 12 hours is indicated.

1. Arterial catheterization can identify and treat vasospasm and microvascular thrombosis with tPA or heparin.

2. Reversal of local microvascular thrombosis may restore perfusion before irreversible necrosis and ischemia occur.

3. Several studies have shown significant decrease in amputation and tissue loss with this aggressive protocol.

B. Early regional sympathectomy of an affected extremity is controversial.

VII. PROGNOSIS

A. Tissue necrosis may be superficial with underlying viable tissue.

B. Complete demarcation usually takes several weeks. Therefore, amputation should not be considered until complete tissue loss is established.

C. Cold intolerance and an increased susceptibility to cold injury are likely in the affected part or extremity

STEVENS–JOHNSON SYNDROME (SJS) AND TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS (TEN)

I. ETIOLOGY

A. Both SJS and TEN have widespread necrosis of the superficial portion of the epidermis.

B. SJS/TEN is commonly associated with sulfonamides, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, oxicam NSAIDS, chlormezanone, and carbamazepine. However, a single offending drug is identified in less than 50% of cases.

1. Antibiotic-associated SJS/TEN presents ∼7 days after drug is first taken.

2. Anti-convulsant–associated SJS/TES can present up to 2 months after drug is first taken.

C. TEN can also be caused by staphylococcal infections in immunocompromised patients.

II. CLASSIFICATION

A. SJS: Total involvement less than 10% TBSA. Widespread eythematous or purpuric macules or flat atypical targets are present.

B. Overlap SJS-TEN: Total cutaneous involvement of 10% to 30%. Widespread purpuric macules or flat atypical targets are present.

C. TEN with spots: Total cutaneous involvement of greater than 30% TBSA. Widespread purpuric macules or flat atypical targets are present.

D. TEN without spots: Total cutaneous involvement greater than 10% TBSA. Large epidermal sheets present. No purpuric macules or targets.

III. PRESENTATION

A. Initial symptoms can be a 2- to 3-day prodrome of nonspecific findings like fevers, headaches, and chills.

B. Symptoms of mucosal irritation like conjunctivitis, dysuria, and/or dysphagia may be present. These symptoms are followed by mucosal and cutaneous lesions.

C. Mucosal irritation, typically at two or more sites. Involved sites may include vaginal, urinary, respiratory, gastrointestinal, oral, and/or conjunctival.

D. Skin lesions are diffusely present

1. Lesions are typically erythematous macules with purple, possibly necrotic centers.

2. Nikolsky’s sign is typically positive (rubbing the skin causes exfoliation of outermost layers and/or a new blister to form).

E. Differential diagnosis of acute, diffuse blistering includes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, paraneoplastic pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, acute graft versus host disease, and linear IgA dermatosis

F. Diagnosis of SJS/TEN is largely clinical and can be confirmed by skin biopsy and histology

IV. TREATMENT

A. Discontinue all potentially offending drugs.

B. Transfer to a burn ICU for fluid/electrolyte monitoring, dressing changes, and temperature regulation is recommended.

C. Debride flaccid bullae. Initial wound care with dressing changes until extent of skin loss is known.

D. Empiric systemic antibiotics have been associated with increased mortality and are not indicated.

E. Consider hemodialysis to remove potentially offending drugs with long half-lives.

F. Early opthamology consultation. Over 50% of SJS/TEN patients can develop symblepharon or entropion.

G. Can involve other consultant services (pulmonary, urology, OB/GYN, gastroenterology) as needed.

H. Administration of steroids and IVIG is controversial. TEN is known to overexpress FAS, which promotes apoptosis of keratinocytes by binding to the FAS/CD95 receptor. IVIG blocks the CD95 receptor and has been efficacious in small series of TEN patients.

V. OUTCOMES

SJS has a mortality of between 1% and 5%. TENS has a mortality of up to 44%.

PEARLS

1. Frostbite occurs as a result of slow tissue freezing with ice crystal formation in the tissue.

2. *The most important immediate frostbite intervention is rapid rewarming in a 104 to 108°F water bath. Rewarming should only be performed if no chance of refreezing exists.

3. For stable patients with severe frostbite, urgent transfer to a facility with interventional radiology capabilities is appropriate. Angiography can allow direct intervention on vessels with thrombosis or spasm. This protocol has been associated with significant increase in digit salvage.

4. Avoid amputation for severely frostbitten extremities until complete demarcation is established.

5. SJS/TEN are part of the same disease spectrum with widespread necrosis of the superficial portion of the epidermis and involvement of multiple mucosal surfaces.

6. SJS/TEN management is typically conservative. IVIG has shown effectiveness in small studies.

QUESTIONS YOU WILL BE ASKED

1. Who is at risk for frostbite?

Any patient with cutaneous dilation, decreased awareness of their surroundings, or loss of instinct to seek shelter.

2. What are the most important interventions for frostbite?

Remove the patient from the cold. Once no chance of refreezing exists, rewarm the affected part in 104 to 108°F water bath for 30 minutes.

3. In addition to rewarming and wound care, what else can we do for this patient?

Consultation with interventional radiology. Arterial catheterization can identify and treat vasospasm and microvascular thrombosis. Studies have shown that this intervention can be digit- or limb-saving.

Recommended Readings

Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, Cochran A, Edelman LS, Saffle JR. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142(6):546–551; discussion 551–553. PMID: 17576891.

Gerull R, Nelle M, Schaible T. Toxic eipdermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1521–1532. PMID: 21358399.

Hazin R, Ibrahimi OA, Hazin MI, Kimyai-Asadi A. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2008;40(2):129–138. PMID: 18293143.

Mohr WJ, Jenabzadeh K, Ahrenholz DH. Cold injury. Hand Clin. 2009;25(4):481–496. PMID: 19801122.

Schulz JT, Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, MacKool B, Tompkins RG. A 10-year experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21(3):199–204. PMID: 10850900.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>