Follow-Up After Surgery for Primary Breast Cancer: Breast-Conserving Therapy and Mastectomy

Elizabeth D. Feldman

Wafa Alkhayal

The detection of recurrent or metastatic disease as well as new primary breast cancers is one of the challenges after surgery for breast cancer, whether it be it after breast-conserving therapy (BCT) or mastectomy. The disease may recur in the ipsilateral breast or chest wall, regional lymph nodes, or systemically. Historically, follow-up after primary treatment for breast cancer has focused on early detection, although the optimal strategy remains somewhat controversial. This chapter will review the literature regarding follow-up after both BCT and mastectomy.

Surveillance After Primary Treatment for Breast Cancer

After primary treatment for breast cancer, it is common practice to enter patients into surveillance programs for many years. An analysis of the annual hazard of recurrence rates in patients involved in the seven large Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) trials demonstrated that the annual hazard of recurrence was greatest for the interval between years 1 and 2, peaking at 13%, and then decreasing to year 5 (1). Beyond 5 years, the annual hazard of recurrence declined slowly and averaged about 4.3% each year. The majority of patients who sustain a locoregional recurrence do so within 2 years (2,3). This suggests that follow-up should be most frequent during the first few years after primary treatment and then taper.

The intensity of the follow-up schedule has been the subject of numerous studies (4,5,6,7). Two randomized trials compared the use of minimal versus more intensive follow-up surveillance of women after primary treatment for breast cancer (4,8) (Table 17.1). The Gruppo Italiano Valutazione Interventi in Oncologia (GIVIO) investigators performed a multi-institutional randomized trial of 1,320 women with stages I, II, and III breast cancer who underwent either intensive follow-up including clinical examinations, bone scans, liver ultrasound, chest x-ray, mammography, and laboratory tests or a control regimen that included only clinical examinations and mammography (4). At a median of 71 months of follow-up, there were no differences between the groups in terms of time to detection of recurrence, survival, or health-related quality of life. A second randomized study of 1,243 women who either underwent physician assessment and mammography or intensive surveillance demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference in cumulative mortality at 10 years (8). A cost-benefit analysis of intensive follow-up versus standard clinical follow-up found that the cost of the latter was approximately one third of that of the intensive group, and there was no difference in the number of early detections in either group (9).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting recommends that only regular history and physical examination and mammography be included in routine follow-up (10). In addition, it recommends that examinations be performed every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, every 6 to 12 months for years 4 and 5, and then annually. For patients who have undergone BCT, a mammogram should be obtained at least 6 months after completion of radiation therapy and then annually. Various other guidelines have been issued internationally (10,11,12,13,14) (Table 17.2).

Another question posed has been who should be following these patients. In a study of 968 women with early-stage breast cancer randomized to either follow-up in a cancer center with a specialist or with their primary care physician, Grunfeld et al. demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference in recurrence-related serious clinical events (15). Similarly, a randomized controlled trial of 296 women who received routine follow-up either at a hospital or in a general practice noted that there was no difference in time to confirmation of recurrence between the two groups, anxiety level, or health-related quality of life (7). A Swedish multicenter study examined the role of nurse-led follow-up, finding that there was no difference in terms of patient satisfaction, anxiety or depression, or time to recurrence or death between patients followed by nurse specialists or physicians (5).

Follow-Up After Breast-Conserving Therapy

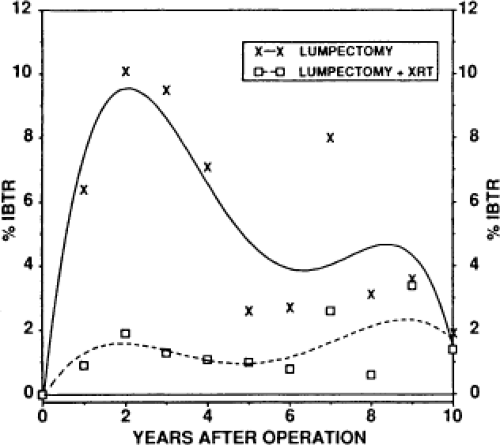

In the last 25 years, the management of breast cancer has changed dramatically. BCT has become widely accepted (16). Although BCT followed by whole-breast irradiation has proven to be effective, women electing to undergo this treatment are faced with the prospect of locoregional recurrence rates of approximately 1% per year (17,18). The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project found a cumulative rate of 14% 20 years after BCT and postoperative radiation therapy (19). The rate was 39% if radiation was not administered (Fig. 17.1).

Detection of Locoregional Recurrence

The most common type of locoregional recurrence, present in 57% to 88% of patients, appears at the site of the primary lesion and probably represents inadequate or incomplete resection of the initial cancer (20,21,22,23,24). The second type, which comprises 22% to 28% of locoregional recurrences, is within

the same quadrant but not directly at the site of the initial tumor (25). The third type of recurrence, within a different quadrant from the initial breast cancer, is found in 10% to 12% of patients and likely represents a new primary (21).

the same quadrant but not directly at the site of the initial tumor (25). The third type of recurrence, within a different quadrant from the initial breast cancer, is found in 10% to 12% of patients and likely represents a new primary (21).

Table 17.1 Randomized Trials of Intensive Schedule Versus Standard Schedule | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The recurrence may be either invasive or in situ carcinoma. For women who are initially treated for an invasive lesion, about 80% recur with another invasive cancer, whereas the remainder have a noninvasive recurrence (26). The question of whether a new noninvasive lesion can be a recurrence or must represent a new primary cancer remains controversial. In patients treated for an initial in situ cancer, 59% will recur with an invasive lesion (27,28). The majority of invasive locoregional recurrences after BCT are detected at an early stage: stage I in 51%, stage II in 34%, stage III in 11%, and stage IV only in 3% of cases (27).

Most recurrences are actually detected by patients themselves, who frequently present at unscheduled or interval visits between follow-up appointments (29,30,31,32,33). A recent meta-analysis, including 5,045 patients, found that 40% of patients with locoregional recurrences were diagnosed during routine clinic visits or testing, whereas the remainder (approximately 60%) developed symptomatic recurrences before their scheduled clinical visits (6). Of the 378 isolated locoregional recurrences identified in this group, 47% were diagnosed after mastectomy and 36% after BCT. Zwaveling et al. noted that only 27% of first recurrences were found specifically as a result of follow-up surveillance (33), as did an analysis of the ECOG database of breast cancer patients enrolled in adjuvant trials, including 208 evaluable patients with relapse, of which only 25% were detected in asymptomatic patients (29). Pivot et al. demonstrated that scheduled follow-up visits detected a mean of 25.9% of relapses during the first 36 months, while after 36 months only 16.3% of relapses were detected by systematic monitoring (34).

History and physical examination should include the identification of abnormal symptoms and/or physical findings of a general medical nature as well as identification of symptoms and physical findings that suggest contralateral breast cancer,

recurrence in the ipsilateral breast following BCT or mastectomy, locoregional or systemic recurrence of disease, or long-term toxicity from therapy (35) (Table 17.3). For women on Tamoxifen, gynecologic symptoms should be reviewed. An increase in firmness in a previous area of thickening or a new palpable mass should prompt further diagnostic procedures including imaging and/or biopsy. However, most clinical findings suggestive of a recurrence can also be attributed to benign processes such as fibrosis and scar formation, fat necrosis, infection, or more nonspecific inflammatory processes.

recurrence in the ipsilateral breast following BCT or mastectomy, locoregional or systemic recurrence of disease, or long-term toxicity from therapy (35) (Table 17.3). For women on Tamoxifen, gynecologic symptoms should be reviewed. An increase in firmness in a previous area of thickening or a new palpable mass should prompt further diagnostic procedures including imaging and/or biopsy. However, most clinical findings suggestive of a recurrence can also be attributed to benign processes such as fibrosis and scar formation, fat necrosis, infection, or more nonspecific inflammatory processes.

Table 17.2 Recommended Surveillance Programs Following Therapy for Primary Breast Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Imaging Surveillance

While other aspects of follow-up care remain disputed, there is a general consensus among experts and evidence to recommend routine surveillance mammograms posttreatment (36,37,38,39). A meta-analysis of 15 studies by Grunfeld et al. observed that ipsilateral recurrence was detected by mammography alone in less than half of breast cancer cases (range 8% to 50%) (40). The remainder was detected by physical examination or by a combination of a physical examination and mammogram. Although many studies report that the method of detection of ipsilateral locoregional recurrences does not influence overall or disease-free survival rates, there is a suggestion that mammography is of benefit over other forms of surveillance, such as physical examination alone (38,41). In fact, detection rates of 34% to 35% by mammography alone argue to the fact that mammography should be an integral part of posttreatment surveillance (42,43).

The optimal timing of the initial posttreatment mammogram remains unclear. Lin et al. addressed this issue in a retrospective study of 408 patients in which postoperative mammograms performed before 12 months noted only 2 noninvasive recurrences (0.49 recurrence per 100 mammograms performed) (44). They also postulated that the financial burden of the initial short interval mammogram would add approximately 7 million dollars to direct health care costs without clear benefit in improving the cancer detection rate.

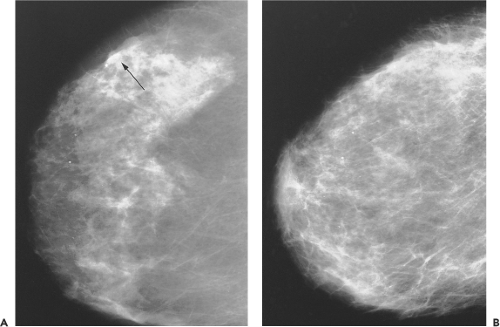

Some studies suggest that posttreatment mammograms serve as a new baseline for subsequent mammograms (45,46). Surgery and radiation in BCT cause changes in mammographic findings that may diminish its sensitivity (45). These changes include architectural distortion, increased density, skin thickening, and microcalcifications (Fig. 17.2).

Microcalcifications noted on mammogram can pose a diagnostic dilemma for radiologists when considering the treated breast and may be indistinguishable from local recurrence. A retrospective review by Gunhan-Bilgen and Oktay of mammographic features of conservatively treated breasts observed that the initial time to development of new microcalcifications in the 68 cases observed ranged from 6 to 90 months, with a mean of 32 months and a median 24 months (46). The authors also reported that 93% of the newly developed microcalcifications were located in the same quadrant as the primary tumor, and 6% of these represented recurrences.

Stomper et al. reported that 43% of mammographically detected recurrences manifested as microcalcifications, indicating

that microcalcifications may be among the most important markers of recurrent breast cancer (42). Similarly, Pinsky et al. showed in a retrospective review of the mammographic appearance of recurrences after ductal carcinoma in situ treated with BCT that 75% of recurrences appeared as microcalcifications and only 18% as masses (37). Several studies have concluded that the incidence of benign disease in patients noted to have suspicious microcalcifications on mammograms varies from 42% to 85% (42,47,48).

that microcalcifications may be among the most important markers of recurrent breast cancer (42). Similarly, Pinsky et al. showed in a retrospective review of the mammographic appearance of recurrences after ductal carcinoma in situ treated with BCT that 75% of recurrences appeared as microcalcifications and only 18% as masses (37). Several studies have concluded that the incidence of benign disease in patients noted to have suspicious microcalcifications on mammograms varies from 42% to 85% (42,47,48).

Table 17.3 Signs and Symptoms Suggestive of Recurrence Following Therapy for Primary Breast Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The patterns of the microcalcifications may provide some insight as to their nature. Radiologists evaluate microcalcifications on the mammogram of a treated breast based on morphology and distributional features much like they do in the preoperative stage. Coarse, fine, dystrophic, and/or punctuate calcifications can be a consequence of therapy. On the other hand, irregular, linear or branching pleomorphic calcifications may signify recurrence (46). A study by Dershaw et al. reviewed the patterns of calcifications associated with tumor recurrence: greater than 10 calcifications, 77%; linear, 68%; pleomorphic, 77%; clustered, 73%; and segmental, 18% (49).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline recommendations in 2006 for breast cancer follow-up, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and Health Canada’s Canadian Breast Cancer Initiative all recommend annual mammography as well as clinical examination as the foundation of the follow-up of breast cancer (10,11,12) (see Table 17.2). Both ASCO and NCCN recommend that the first posttreatment mammogram be no earlier than 6 months after radiation therapy with a subsequent mammogram every 6 to 12 months thereafter for the surveillance of abnormalities (10,11). Once stability of findings is achieved, progression to yearly mammograms is advised.

The use of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to screen for ipsilateral locoregional recurrence in patients treated with BCT remains controversial. Gorechlad et al. performed a retrospective analysis of the use of breast MRI as a screening tool to detect recurrence after BCT (50). They found that only 1.7% of patients developed ipsilateral breast recurrence, with a mean tumor diameter of 1.6 cm, in a review of 476 tumor excisions with a mean follow-up of 5.4 years. Contralateral disease developed in 2.3%, with a mean tumor diameter of 1.5 cm. They concluded that the use of annual MRI in addition to mammography and physical exam would not have been cost-effective as a screening measure.

Currently, ASCO guidelines recommend that the decision to obtain MRI in surveillance should be made on an individual basis with regards to the clinical scenario (10). Women with a very high risk of contralateral recurrence such as BRCA-1/2 gene mutation carriers who have undergone surgery for breast cancer have a 27% 10-year risk of contralateral breast cancer, such that they may benefit from screening with MRI. Another subset of patients who may undergo screening MRI are patients who have had tumors that have been not been reliably detected by physical examination or mammography in the past. This group may include patients with initial mammographically occult cancers, patients with very dense breasts on mammography, and patients with infiltrating lobular carcinomas, although there is no evidence in the literature to support such a practice.

Management of Locoregional Recurrence

From 5% to 12% of patients with locoregional recurrence will be found to have inoperable disease at the time of diagnosis (20,51,52). Therefore, a metastatic work-up including computed

axial tomography scans and bone scans is reasonable prior to operative intervention for locoregional recurrence. The recommended treatment for local recurrence after BCT is most often salvage mastectomy (2,21,28). It is relatively successful in controlling local disease, with an incidence of second locoregional recurrence ranging from 4% to 37% (51,52,53). The median time to failure after salvage mastectomy is 18 months (51). As the previously irradiated breast has damaged skin, the use of autologous tissue flaps for reconstruction is preferred over tissue expansion and subsequent implant placement (21).

axial tomography scans and bone scans is reasonable prior to operative intervention for locoregional recurrence. The recommended treatment for local recurrence after BCT is most often salvage mastectomy (2,21,28). It is relatively successful in controlling local disease, with an incidence of second locoregional recurrence ranging from 4% to 37% (51,52,53). The median time to failure after salvage mastectomy is 18 months (51). As the previously irradiated breast has damaged skin, the use of autologous tissue flaps for reconstruction is preferred over tissue expansion and subsequent implant placement (21).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree