Fat Grafting in Plastic Surgery

Louis P. Bucky

Ivona Percec

Daniel Del Alexander Vecchio

INTRODUCTION

The role of autologous fat grafting or fat auto-transplantation in plastic surgery has evolved from a controversial technique designed for simple volume augmentation to the foundation for the innovative and burgeoning field of regenerative medicine. Neuber (1893) initially reported the use of small pieces of fat from the upper arm to reconstruct a depressed area of the face resulting from tuberculous osteitis. Today, fat grafting plays diverse and far-reaching roles in plastic surgery. Its application currently extends from simple volume augmentation of the face to total reconstruction of a post-mastectomy breast. Because many of the variables in fat transplantation were not well understood initially, early results with fat grafting were disappointing, and the technique was largely abandoned.

Recent enhancements in fat grafting applications lie not only in more reliable volume augmentation to the face, breast, and buttocks, but perhaps more importantly in pioneering the potential regenerative aspects of fat via its rich source of stem cells. Though fat grafting to the face has been used relatively consistently since the introduction of the Coleman technique in the mid-1990s, fat transplantation to the breast and body was largely abandoned for more than 20 years. By 2006, reports of fat transplantation emerged in presentations and in case report papers suggesting the long-term viability of fat transplantation to the breast. In 2007, Coleman published his review of 17 patients who were grafted using autologous fat and were followed up with serial photography. The specific grafting techniques employed in a given case depend upon a series of factors, including the characteristics of the recipient site, the goals of surgery (volume and shape), and abundance of donor tissue. Because of the intrinsic differences in fat grafting to the face versus the body, this chapter has been divided into fat grafting applications for cosmetic and reconstructive uses in the face followed by large volume fat grafting applications for the breast and body.

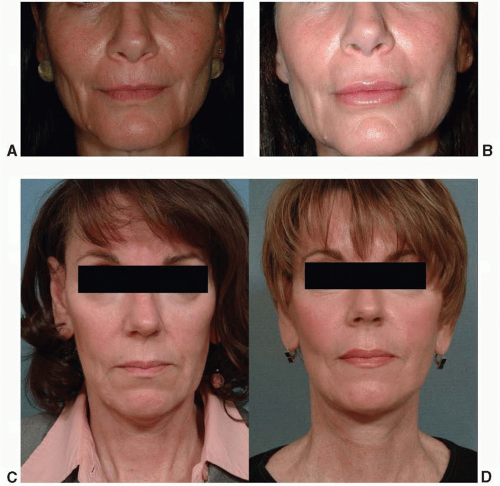

FACIAL FAT GRAFTING

Autologous fat grafting to the face provides a naturally appealing solution to a vital aspect of facial aging. Soft tissue loss or deflation occurs routinely in middle-aged adults. As fat content is reduced, soft tissues collapse and the face globally “deflates” permitting gravitational changes to arise. Lipoatrophy in the face can also result from disorders such as Perry-Romberg syndrome, trauma, and infection. Hypoplasia of fat can be congenital, as in hemifacial microsomia (Figure 44.1). The use of fat as a filler for volume restoration of the face is optimal due to its easy acceptance, excellent safety profile, and natural appearance and feel. Historically, the major limitation of fat grafting has been unpredictability of “take” or viability, typically ranging from 40% to 60% of what has been grafted. In our experience, small volume fat grafting to the face behaves like other biologic grafting in that it requires adequate vascularization of grafted tissue for long-term viability. Fat grafting to the face, as opposed to the body, utilizes concentrated smaller volumes of fat, typically 20 to 60 cc of purified fat. Since large volumes are not necessary, and overfilling is undesirable in the face, gentle harvest, adequate processing, and small volume injection become even more paramount as the tenets of successful fat grafting technique.

Managing the Variables—From Donor to Recipient

Donor and Harvest.

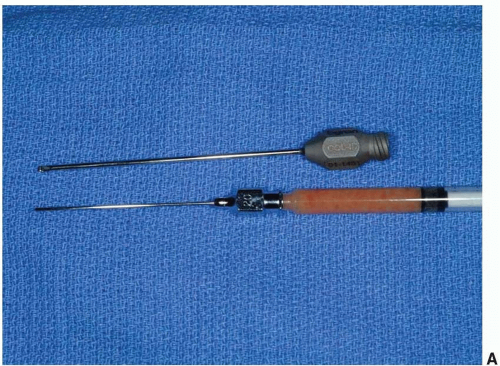

The most common graft donor sites are the hips, saddlebags, thighs, abdomen, and inner knee. There are no data that suggest one anatomical site is superior to another, yet all donor sites need to have adequate fat volume to avoid a potential concavity or dimpling deformity after harvest. Infrequently, harvesting from more than one site is necessary to acquire sufficient volume for grafting. Pre-infiltration with dilute lidocaine and epinephrine into donor sites typically provides adequate graft volume, hemostasis, and analgesia. Most surgeons employ a version of the Coleman technique that calls for gentle suction through small 10 cc syringes and microinjection using 1 cc blunt-end cannulae. Usually, this technique results in a 3:1 ratio of harvested to purified fat.

Fat Preparation.

Fat must be processed to separate oil, blood, and lidocaine from potentially viable fat cells. This can be accomplished by gravity sedimentation, by centrifugation, by Telfa pad rolling, or by a combination of these techniques. There are no current data to suggest one technique is superior to another. Irrespective of purification technique, the limitation of ischemic time and cellular trauma should be a priority. For low volume augmentation, we prefer gravity sedimentation followed by Telfa rolling until the fat becomes yellow in color and thick in consistency, as unwanted fluids are absorbed. The fat is then gently transferred into 1 cc syringes prior to injection (Figure 44.1).

Fat Grafting Injection.

Small aliquots of fat are microinjected into discrete facial units using a 1 cc syringe, with the goal of predictable viability and avoidance of contour irregularities (Figure 44.2). Areas of the face that have the least motion have the best survival outcomes. Therefore, the deep compartments of the cheek, malar, and upper nasolabial folds are excellent recipient sites due to their relative immobility, preexisting fat content, and depth of location (Figure 44.1). The perioral region, lips, marionettes, and lower nasolabial folds are more variable due to significant motion and thinner overlying tissues (Figure 44.3). In contrast, the periorbital region has excellent survival of small volumes, but is perhaps the most challenging due to its thin, delicate, and unforgiving nature. Filling to the periorbital region should be limited to small volumes using small blunt cannulae with injections placed under the orbicularis oculi muscle. In areas of significant motion such as the glabella, results are best obtained when fat infiltration is preceded by neuromodulation to limit muscle motion. Additional regions where fat grafting can be used successfully are the temples, forehead, prejowl sulci, and labiomental crease.

Complications.

The complications of facial fat grafting are typically limited to contour irregularities secondary to superficial placement and fat necrosis, frequently in the older patient. Both usually necessitate direct excision. Variable graft survival is still common, though it can be limited by attention to detail, careful preparation, and infiltration. The two most significant complications are intravascular injection and

overgrafting. Fortunately, these phenomena are exceedingly rare. Injection injury can be limited by using blunt cannulae and low-pressure injection in a layered fashion. On the contrary, overgrafting is becoming an increasing problem due to large volume injection, as practitioners become more at ease with fat grafting techniques. This is seen more frequently in younger patients who have had superficially placed injections. Unfortunately, weight gain causes all fat grafts to enlarge, which, in the face, can result in significant and disproportionate distortion. The treatment of overgrafting requires microliposuction with only limited improvements and risks of excessive scar formation. Therefore, even for experienced surgeons, it is recommended to use small to moderate grafts in the face with minimal overfilling in most patients.

overgrafting. Fortunately, these phenomena are exceedingly rare. Injection injury can be limited by using blunt cannulae and low-pressure injection in a layered fashion. On the contrary, overgrafting is becoming an increasing problem due to large volume injection, as practitioners become more at ease with fat grafting techniques. This is seen more frequently in younger patients who have had superficially placed injections. Unfortunately, weight gain causes all fat grafts to enlarge, which, in the face, can result in significant and disproportionate distortion. The treatment of overgrafting requires microliposuction with only limited improvements and risks of excessive scar formation. Therefore, even for experienced surgeons, it is recommended to use small to moderate grafts in the face with minimal overfilling in most patients.

TABLE 44.1 A SUMMARY OF FACIAL AND MEGA-VOLUME TECHNIQUE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree