Facelift

Charles H. Thorne

No procedure is more closely associated with plastic surgery in the eyes of the public than facelifting, and perhaps rightfully so. When performed with appropriate attention to detail in a properly selected patient, the procedure provides consistently satisfactory results, creating a natural, unoperated appearance and leaving the patient looking like a crisper version of himself or herself. When not properly performed, the procedure can be catastrophic, resulting in visible scars, distorted ears and hairlines, unnatural creases, and a disharmonious, obviously operated look.

This chapter summarizes the author’s personal approach to facelifting, as well as the most common techniques employed by other plastic surgeons. Many of the components of the procedure are easily summarized in a chapter of this type; other components such as how much to do, and how tight to pull, are difficult to describe in words, vary between patients, and require experience to master.

In the author’s opinion, there is one principle of overriding importance in facelifting and in selecting the ancillary procedures to be performed concomitantly with faceliftng: The surgeon should always perform the fewest number of maneuvers and the simplest possible maneuvers in order to address the patient’s complaints in a realistic fashion. The more that is done, the longer the recovery but more importantly, the more likely that the patient will have an operated look or a complication. Less is more.

STATE OF THE ART

Facelifting was first performed in the early 1900s and for most of the 20th century involved skin undermining and skin excision. A revolution occurred in the 1970s when the public became exponentially more interested in the procedure and Skoog described dissection of the superficial fascia of the face in continuity with the platysma in the neck. Since then techniques have been described that involve every possible skin incision, plane of dissection, extent of tissue manipulation, type of instrumentation, and method of fixation. Many of these “innovations” provide little long-term benefit when compared with skin undermining, and expose the patient to more risk. The trends in facelifting at the present time are best summarized as follows:

Volume versus tension—Placing tension on the skin is an ineffective way of lifting the face and is responsible for the “facelifted” look and for unsightly scars and distortion of the facial landmarks such as the hairline and ear. The current trend is toward redistributing, or augmenting, facial volume, rather than flattening it with excessive tension. The redraping of skin flaps in facelifting is more of a rotation than it is a direct advancement under tension.

Less invasive—Some of the more “invasive” techniques have not yielded benefits in proportion to their risk. This, combined with the public demand for rapid recovery, has led to simplified procedures. It is the author’s impression, however, that the pendulum has swung back somewhat away from the least invasive procedures because of inadequate correction of aging changes with these less invasive techniques. The author tends to employ a high, extended superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) procedure with open treatment of the submental region in the majority of patients, a procedure that lies toward the invasive end of the facelift spectrum.

Facial harmony—The goal is to help a patient look better, not weird or operated on. Excessive tension, radical defatting, exaggerated changes, and attention to one region while ignoring another may result in disharmony. The face is best analyzed and manipulated with the entire face (and the entire patient) in mind, not the individual component parts, lest the “forest be lost for the trees.”

Recognition of atrophy—The process of aging involves not only sagging of the tissues and deterioration of the skin itself but also atrophy of tissues, especially fat, in certain areas. Most patients are best served with limited defatting and may require addition of fat to areas of atrophy. It is the author’s impression that fat grafting at the time of facial cosmetic surgery has also swung back slightly in the direction of conservatism. Too much fat grafting can result in a large, puffy face which is less attractive than the atrophied face that the patient started with.

BENEFITS AND LIMITATIONS OF FACELIFTING

Facelifting addresses only ptosis and atrophy of facial tissues. It does not address, and has no effect on, the quality of the facial skin itself. Consequently, facelifting is not a treatment for wrinkles, sun damage, creases, or irregular pigmentation. Fine wrinkles and irregular pigmentation are best treated with skin care and resurfacing procedures (see Chapters 13 and 41). Most facial creases will not be improved by facelifting (nasolabial creases), and even if improved somewhat, may still require additional treatment in the form of fillers or muscle-weakening agents (see Chapters 42 and 43).

The above disclaimer notwithstanding, the facelift is the single most important and beneficial treatment for most patients older than 40 years who wish to maximally address facial aging changes. Patients who believe that fillers and neurotoxins can be used instead of, or to delay, a facelift are generally incorrect. Injectables can be complimentary to facelifting but do not address the same aging changes as facelifting.

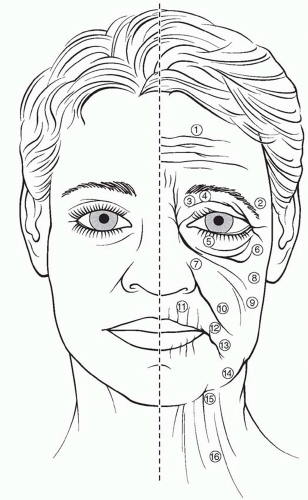

Patients have individual aging patterns determined by genetics, skeletal support, and environmental influences (Figure 47.1). Some combination of the following, however, will occur in every patient (those characteristics improved by facelifting are in bold—a minority of the changes enumerated):

Forehead and glabellar creases

Ptosis of the lateral eyebrow

Redundant upper eyelid skin

Hollowing of the upper orbit

Lower eyelid laxity and wrinkles

Lower eyelid bags

Deepening of the nasojugal groove and palpebral-malar groove

Ptosis of the malar tissues

Generalized skin laxity

Deepening of the nasolabial folds

Perioral wrinkles

Downturn of the oral commissures

Deepening of the labiomental creases

Jowls

Loss of neck definition and excess fat in neck

Platysmal bands

A minority of aging characteristics is improved by facelifting. Those that are addressed, however, are of fundamental importance to the attractive, youthful face. The facelift confers another benefit that is more difficult to define. Aging results in jowls and a rectangular lower face. A facelift lifts the jowls back into the face, augmenting the upper face and narrowing the lower face, producing the “inverted cone of youth.” This change in overall facial shape from rectangular to heart shaped is subtle but real and is a benefit that no other treatment modality can provide.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

History

The same compulsive medical history that is indicated before any surgical procedure is obtained when evaluating a patient for aesthetic surgery of the face. Specific inquiry is made regarding medications, allergies, medical problems, previous surgery, and smoking and drinking habits. The most common complication of facelifting is a hematoma and therefore the history focuses on factors that predispose to postoperative bleeding, specifically hypertension and medications that affect clotting. Surgery is not performed until the patient has been off of aspirin for 2 weeks. Facelifting is probably contraindicated in patients on warfarin (Coumadin) or clopidogrel (Plavix), even if they are allowed by their physicians to stop these medications. At the very least, facelifting on such patients is performed with extreme conservatism and only after every possible means of eliminating the effects of these medications has been pursued. Hypertension is probably the single factor that most closely correlates with postoperative hematomas; thus, blood pressure must be under strict control. While consultation with an internist may be helpful in managing blood pressure, the plastic surgeon must be facile with antihypertensive medications and, in the author’s opinion, be involved with every decision regarding blood pressure and blood pressure management in the perioperative period.

Cigarette Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of skin slough, the second most common complication after facelifting.1 Patients are encouraged to quit smoking permanently. Cigarette smoking, with all its deleterious effects on health, and having a facelift to feel better about oneself are fundamentally contradictory. At the very least, patients should cease smoking 2 weeks prior to surgery. It is important that smokers know that they will never become “nonsmokers”; that is, the effects of smoking never totally disappear and are certainly not gone in 2 weeks.

Because aesthetic surgery is elective, whenever there is a question about a preoperative medical condition, the procedure is postponed until appropriate consultations are obtained and all issues settled.

Preoperative Photographs

Photographs are essential for at least four reasons: (a) assistance in preoperative planning; (b) communication with patients preoperatively and postoperatively; (c) intraoperative decision making; and (d) medicolegal documentation.

Psychological Considerations

One of the most difficult challenges for the plastic surgeon is deciding which patients are not candidates, on an emotional or psychological basis, for elective aesthetic surgery. Studies suggest that patients frequently harbor secret or unconscious motivations for undergoing the procedure. A patient may state that he/she wants to feel better about himself or herself when the real motivation is to recapture a straying mate (unlikely to succeed).

Patients who have difficulty delineating the anatomic alterations desired or in whom the degree of the deformity does not correlate with the degree of personal misfortune ascribed to that deformity are not candidates for aesthetic surgery. The demanding, intimidating, 50-year-old lawyer who states that she does not like her jowls is a far better candidate than the seemingly docile patient who cannot articulate what bothers her and defers to “whatever you think doctor.” The surgeon will regret proceeding with an operation when his or her instincts indicate that the patient is an inappropriate candidate.

Preoperative Counseling

At the time of the preoperative consultation, the patient is given written information concerning the planned procedure that reinforces the verbal information provided.

In addition to describing to the patient the anticipated results of the procedure, it is necessary to point out the areas where little or no benefit is expected. As described above, the

nasolabial creases may be softened slightly by a facelift but will reappear when the swelling disappears. Ptotic submandibular glands preclude a totally clean appearance to the neck. Fine wrinkles around the mouth will require a resurfacing procedure.

nasolabial creases may be softened slightly by a facelift but will reappear when the swelling disappears. Ptotic submandibular glands preclude a totally clean appearance to the neck. Fine wrinkles around the mouth will require a resurfacing procedure.

Preoperative Instructions

Patients are instructed to shower and wash their hair on the night before surgery. On the morning of surgery another shower and shampoo are desirable. At a minimum, the face is thoroughly washed. Although patients are not allowed to eat anything after midnight, they are instructed to brush their teeth and rinse their mouths with mouthwash.

Given that the single most important step in avoiding a hematoma is control of the blood pressure, patients with any tendency to high blood pressure are given clonidine 0.1 mg by mouth preoperatively. Some surgeons administer the drug routinely to all patients. Clonidine is long-acting, however, and may lead to hypotension in healthy patients. Consequently, this author prefers to use it selectively.

ANESTHESIA

The subjects of anesthesia and which technique is the safest are poorly understood by patients. A facelift can be safely performed under local anesthesia with sedation provided by the surgeon, under intravenous sedation provided by an anesthesiologist, or under general anesthesia. If the surgeon is to perform the procedure without an anesthesiologist, the patient must be completely healthy. The patient is given diazepam (Valium) 10 mg by mouth 2 hours preoperatively and brought to the facility by an escort. Meperidine (Demerol) 75 mg and hydroxyzine pamoate (Vistaril) 75 mg are administered intramuscularly. Once the effect is demonstrable, the patient is moved to the operating room to initiate the procedure. Midazolam (Versed) is given intravenously in 1-mg increments until the patient is sufficiently sedated to tolerate the injections of local anesthetic solution. Additional midazolam (Versed) is given as needed throughout the procedure, also in 1-mg doses.

In most cases, however, facelifts are performed with the help of an anesthesiologist. If the procedure is to be longer than 3 hours because of ancillary procedures, or if the patient has medical problems, then an anesthesiologist is always present.

The anesthesiologist decides where on the spectrum from conscious sedation to general anesthesia the patient is best kept, and it may vary during a procedure. The patient may be under general anesthesia, by any definition, during the injection of the local anesthetic solution, and conscious during other phases of the procedure. In other patients, despite the efforts of the anesthesiologist to provide conscious sedation, the medication will result in loss of the airway, requiring that the anesthesiologist converts the procedure to general anesthesia.

Patients and some other physicians incorrectly believe that patients are safer with “twilight” anesthesia, whatever that is. Local anesthesia is safe and general anesthesia is usually safe, but the least safe anesthetic and the one requiring the most skill to administer is the “in between” anesthetic that patients call “twilight.” Patients who are sedated but who do not have an endotracheal tube in place to control the airway are more likely to have airway problems than a patient who is completely asleep with the ventilation controlled by the anesthesiologist. Many patients who undergo facelift procedures believe they are receiving “sedation,” but they are really receiving intravenous, general anesthesia without an endotracheal tube. There is nothing wrong with the technique in the hands of an expert, but patients should be disabused of the notion that it is safer than general anesthesia.

Blood Pressure Control

An ideal anesthetic for facelifting would be associated with a constant blood pressure and no need for vasoactive medications to either raise or lower it. Dips in blood pressure treated with vasoconstrictors, or spikes in blood pressure treated with vasodilators, are to be avoided if at all possible. Blood pressure is ideally kept at approximately 100 mm Hg systolic, depending on the patient’s preoperative blood pressure. Excessive hypotension may obscure bleeding vessels that are best coagulated. Hypertension may be associated with excessive bleeding. The anesthesiologist should inform the surgeon of every medication administered, and the surgeon should inform the anesthesiologist of any increased tendency for bleeding. There are no secrets in the operating room. The surgeon will be managing the patient postoperatively so it behooves him/her to learn as much as possible from the anesthesiologist about the particular patient’s blood pressure and response to any agents employed intraoperatively.

Local Anesthetic Solution

Regardless of the type of sedation/anesthesia chosen, the face is injected with local anesthetic solution prior to the dissection. There is some controversy and little definitive data regarding the maximal amount of local anesthetic that can be used. The package insert in the lidocaine bottle states that no more than 7.5 mg/kg of lidocaine should be administered when given in combination with epinephrine. We know, however, that when dilute solutions are used in liposuction of the body, more than 30 mg/kg of lidocaine is safe. There is evidence that the face differs from the body and that the lidocaine doses used in the body are too high for the face. It is reasonable to conclude that doses higher than the 7.5 mg/kg recommended by the manufacturer but less than the 30 mg/kg used in the body are probably safe in the face, but this is unproven. Until such proof exists, plastic surgeons should limit the total dose to approximately 7.5 mg/kg. In the author’s practice, the author dilutes 500 mg lidocaine (one 50 mL vial of 1% lidocaine, which is the approximate maximum dose for a 70-kg patient) to whatever volume is necessary to perform the entire procedure, no matter how dilute that solution is.

The most common solution used by the author is 50 mL 1% lidocaine plus 1 mL epinephrine 1:1,000 plus 250 mL normal saline for a final volume of 301 mL and a final solution concentration of 0.17% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:300,000.

Because of the dilute nature of the solution used and the fact that the total dose of lidocaine does not exceed the manufacturer’s recommendation, the author usually injected both sides of the face at the beginning of the procedure, despite recommendations by some that only one side should be injected at a time. If the patient has an especially heavy neck or is a large male patient, the author may inject one side at a time because the first side will be more time-consuming than average.

If the patient is adequately anesthetized, the injection of the anesthetic solution is rarely accompanied by any change in heart rate or blood pressure. The surgeon must constantly keep the injecting needle moving, however, to avoid a large intravascular injection of the epinephrine-containing solution. If a major change in blood pressure occurs, the surgeon and anesthesiologist must assume that an intravascular injection has occurred and must act quickly to limit the extent of hypertension.

FACELIFT ANATOMY

If either skin undermining alone or subperiosteal undermining alone is performed, the surgeon can, to some extent, ignore the anatomy. These two planes of dissection are safe.

Manipulation of the tissues between these two planes, however, necessitates an understanding of and constant attention to the anatomy to avoid complications.

Manipulation of the tissues between these two planes, however, necessitates an understanding of and constant attention to the anatomy to avoid complications.

Anatomic Layers

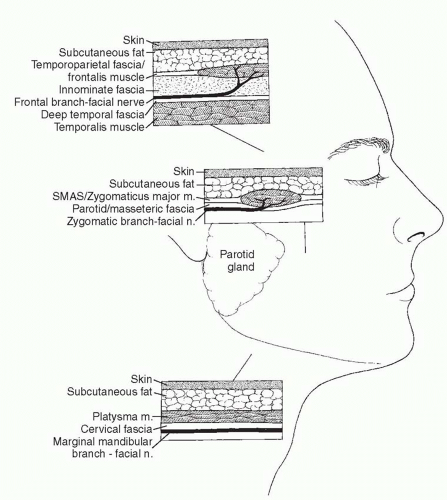

There are five layers of critical anatomy: skin, subcutaneous fat, the SMAS-muscle layer, a thin layer of transparent fascia, and the branches of the facial nerve (Figure 47.2). These five layers are present in all areas of the face, forehead, and neck, but they vary in quality and thickness, depending on the anatomic area.

The first two layers, the skin and subcutaneous fat, are self-explanatory. The third layer (SMAS) is the most heterogeneous.2 It is fibrous, muscular, or fatty, depending on the location in the face. The muscles of facial expression are part of the SMAS layer (e.g., frontalis, orbicularis oculi, zygomaticus major and minor, and platysma). In the temporal region, this layer is not muscular but is fascial in quality and is represented by the superficial temporal fascia (or temporoparietal fascia).

The fourth layer consists of a layer of areolar tissue that is not impressive in thickness or strength, but is always present and is a key guide to the surgeon as to the location of the facial nerve branches. In the temporal area, this layer is known as the innominate or subgaleal fascia; in the cheek, it is the parotid-masseteric fascia; and in the neck, it is the superficial cervical fascia. Once under the SMAS, the facial nerve branches can be seen through this fourth layer. If the layer is kept intact, it serves as verification to the surgeon that he or she is in the correct plane of dissection. If a nerve branch is encountered without this fascial covering, the surgeon must be aware that the dissection is too deep and nerve branches may have been transected. Just as it is convenient, but not totally accurate, to think of the galea-frontalis-temporoparietal fascia-SMAS-orbicularis oculi-platysma as a single layer, it is useful to think of the subgaleal fascia-innominate fascia-parotid/masseteric fascia-superficial cervical fascia as a single layer.

The fifth layer is the facial nerve, which is discussed in detail below.

Facial Nerve

If the surgeon remembers that the facial nerve branches innervate the respective facial muscles via their deep surfaces, the safe planes of dissection become obvious. Dissection in the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the SMAS-muscle layer, is safely performed anywhere in the face, whether it is the temporal region, cheek, or neck. Dissection deep to the SMAS, superficial to the facial nerve branches, requires care.

There are three to five frontal (or temporal) branches of the facial nerve that cross the zygomatic arch and innervate the frontalis muscle, orbicularis oculi, and corrugator muscles via their deep surfaces.3 Because the layers of anatomy, although present, are compressed over the arch, these branches are vulnerable to injury in this region. Dissection in this region can either be performed superficial to the nerve branches in the subcutaneous plane, or deep to the branches on the surface of the temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia).4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree